"As good as D’arcy and James are, it was just going to sound better if Billy played it" – Billy Corgan, Jimmy Chamberlin, Butch Vig, Flood and more on the Smashing Pumpkins' recording history

Classic interview – From Gish to Zeitgeist, through the eyes of the key players… plus the 11 underrated Pumpkins songs guitarists need to hear

"I'm sorry, I’m on a tangent,” he laughs. “See, I told you. I don’t interview anymore. I’m just talking like a normal person.”

It’s ten minutes into our first interview, and Billy Corgan has gone slightly off-topic. Nothing too outlandish, but he’s affable and apologetic nonetheless. The two of us are sitting on the patio outside a nondescript home studio in Los Angeles, where the audio is being mixed for a forthcoming DVD chronicling the Smashing Pumpkins’ 12-show run at the Fillmore in the summer of 2007.

In two weeks he’ll travel to another studio to record G.L.O.W., a new Pumpkins track for the Guitar Hero World Tour video game. Corgan also went through facial scanning and motion capture at Neversoft to become a playable character.

“Digital me,” he smiles, right down to the sheen off his dome piece. There’s a lot on tap in Pumpkinland, but for the moment its chief resident is calm and centred. The loudest thing about him is a pair of bright orange socks peering over the top of his black-and-red high-top Nike Court Forces.

That anybody would announce the fact that they were talking like a normal person seems strange unless that person happens to be Billy Corgan. Frequently misinterpreted and misquoted, it’s understandable that Corgan is somewhat of a guarded interview, at least in regards to certain topics. Gear isn’t one of them.

“I love talking about that stuff,” he says. “I’d rather talk about that stuff than talk about emotional stuff. So yeah, as far as you want to go down the rabbit hole...”

The thing is, the further down you go, the more you realise that the emotional stuff and the technical stuff intertwine like patch cables. Personalities, playing styles, tension, harmony, exploration everything is interconnected.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Riffs and rifts. Tone and atonement. The collective dynamic among Billy Corgan, drummer Jimmy Chamberlin, guitarist James Iha, and bassist D’arcy Wretzky manifested itself in one of the most sonically diverse and emotionally-complex bodies of work in rock history.

As individuals, they affected one another just as much with their absence as they did with their presence. They are torchbearers of the Alternative Nation, and their music resonates with hippies, shoegazers, goths, shredders, and e-music experimentalists alike.

“Thousands of songs have come and gone over the past 20 years, but we can count on one hand the iconic bands that are a staple in the format,” says Michael Martin, Vice President of Programming at 98.7 KYSR in Los Angeles. “We test thousands of records in a year, and Smashing Pumpkins are always near the top with multiple tracks. It’s beyond the single and beyond the album. It’s the band.”

Jimmy Chamberlin on drum education, developing your style and the mechanics of drumming

With Corgan at the helm, the Pumpkins filtered their concepts through a gamut of accredited producers, engineers, and mixers, achieving unique creative and critical outcomes for each project. The motivation, whether conscious or subconscious, remained the same: Move forward, apply pressure, don’t fake it.

“Go back and read the press on us from 1989 to 1992,” says Corgan. “People had no clue who we were and where we were going. We were onto something and we followed it through, and it built up into something that sold and was popular.

The mainstream world only wants to hear you when you have your shit together

Billy Corgan

"It had its moment, but I think once we crested that wave it was back to a level of experimentation. What we didn’t understand were the ramifications it was going to have on the band commercially. You can’t build yourself into this superpower and then say, ‘I’m going to go back to being arty guy.’ They don’t want to hear that, and I wasn’t sophisticated enough to understand that. Now I am.

“The mainstream world only wants to hear you when you have your shit together. It may take us three years to get our shit together to a point where we can make that kind of level of work, and then we’ll show up and we’ll set the phasers to stun. I’m 41, Jimmy’s 44, we still have a good seven-plus years where we can play that kind of music that way. I think Superchrist is a good indication that we’re still willing to light stuff on fire.”

A blunt force psychedelic jam produced by longtime friend Kerry Brown, Superchrist is both a push to the future and a nod to the past. It’s the first fruit of a band no longer beholden to a label, Zeitgeist fulfilled their one-album deal with Warner Brothers and rekindles a raw, brazen energy that, to Brown, was a cornerstone of Gish-era recording.

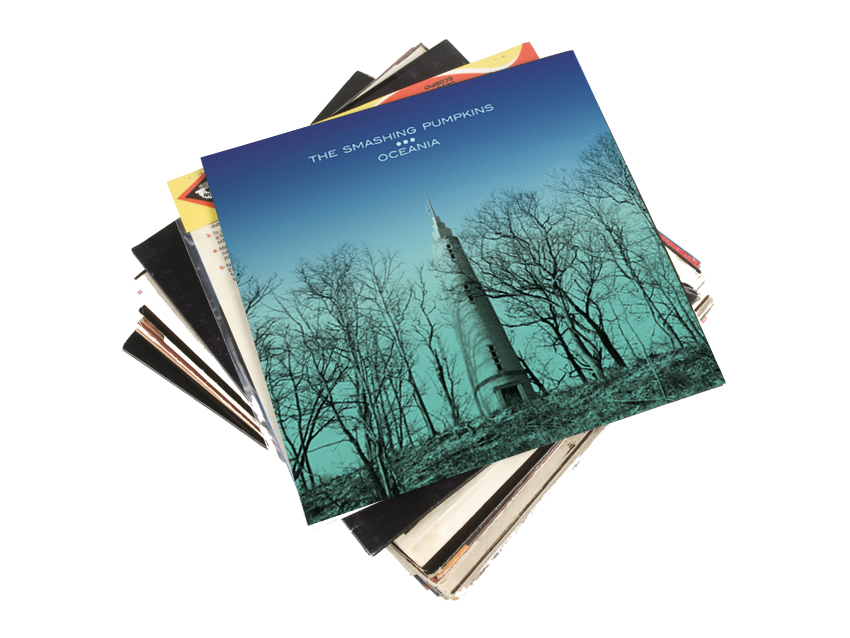

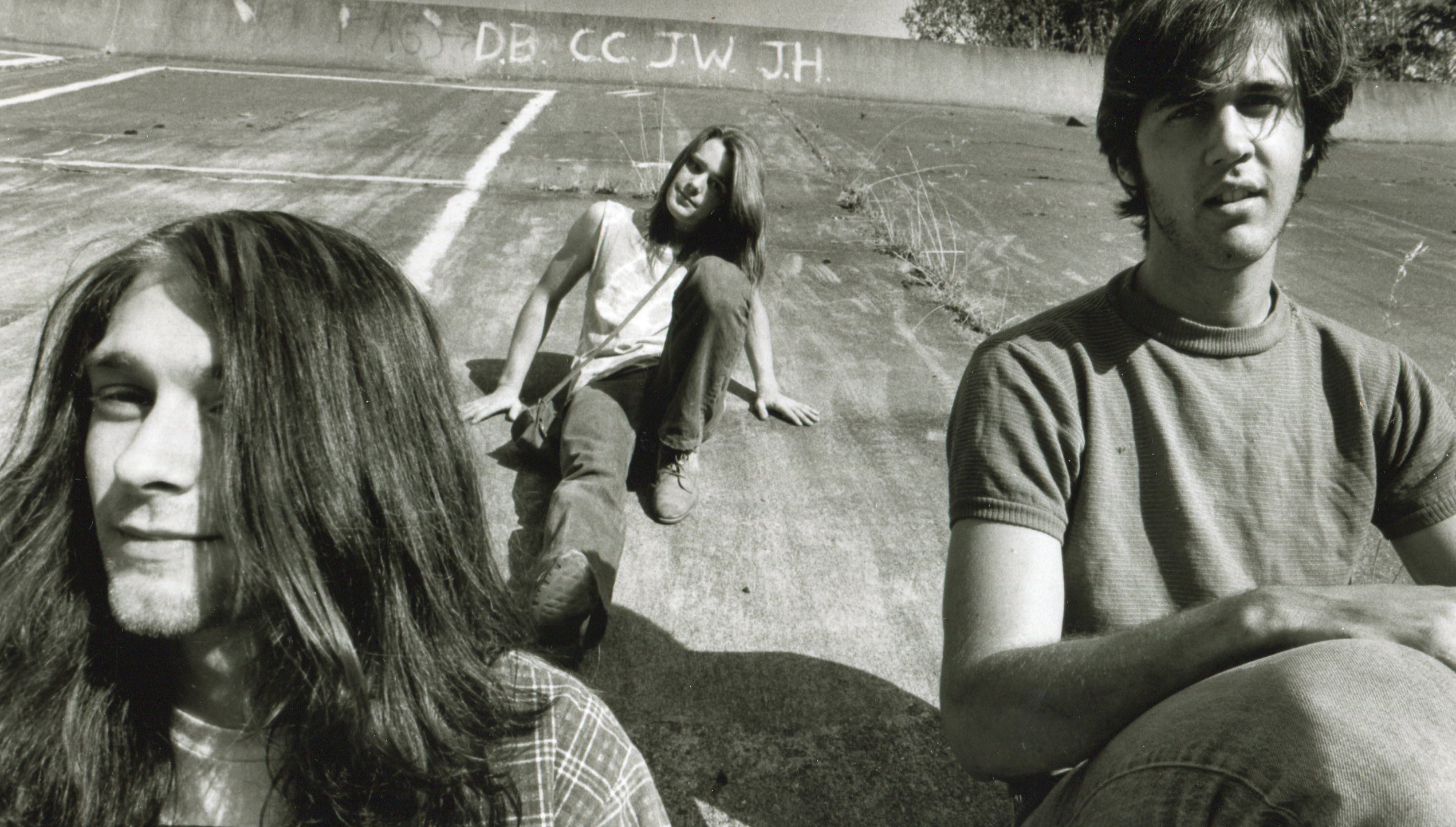

Gish (1991)

If you ever saw that band play live, they could absolutely crush people

Butch Vig

The Smashing Pumpkins rose to prominence in the shadows of Wrigley Field on the North Side of Chicago in the late 1980s. Outfitted in cold weather thrift store threads, they delivered punishing body blows of bombastic, cinematic love-rock, their pop appeal perfectly shaded behind a treacherous wall of sound. Destiny handed them an alternative pedigree, but their cover material, Sookie Sookie (Steppenwolf), The Joker (Steve Miller Band), Venus In Furs (The Velvet Underground), exposed deep roots that would inform their future recordings.

“The Pumpkins looked like they were from Mars,” says producer Butch Vig. “To see how they looked and hear how they sounded was one of the reasons why people thought they were really special. If you ever saw that band play live, they could absolutely crush people.”

The band had already released a self-produced single for I Am One in the spring of 1990 before Corgan contacted Vig about producing a Sub Pop seven-inch for the song Tristessa. The strength of that partnership prompted Vig to sign on for their full-length debut, which was to be recorded at Vig’s Smart Studios in Madison, Wisconsin.

“Billy was very ambitious,” Vig remembers. “He wanted to make everything sound amazing and see how far he could take it; really spend time on the production and the performances. For me, that was a godsend because I was used to doing records for all the indie labels and we only had budgets for three or four days.”

The band loaded into the studio with a modest amount of gear, most of which can be seen in their first few videos. On stage, the band’s signature sound was rooted in Corgan and Iha’s mid-’70s Strat/’87 Les Paul combination, but the recording centred around Corgan’s rig: An early ’80s Marshall JCM800 2203, known as the Soul Head, run through Marshall 1960A cabinets, all purchased off “some stoner guy” in Chicago for $800.

The KT88 tubes in the JCM produce a round, creamy tone that, when used in conjunction with an ADA MP-1 tube preamp, produced the Gish tone. Using the low input side of the JCM, Corgan would turn the master volume all the way up, and then use the preamp’s volume to make micro-adjustments. A host of effects, from the Fender Blender to the Phase 100, were folded in for extra fuzz and sweep comb filtering. The bass parts were recorded with Wretzky’s black Fender P-Bass, dubbed the “Rat Bass” for the scattering of white rat stickers all over the face and played through a Trace Elliot AH300SM.

“Billy was ‘green’ only in the sense that he didn’t necessarily have hands-on experience, but he knew what he wanted,” Vig continues. “He’s a big fan of Queen and ELO, and those records had big produced sounds, and as much as he didn’t know maybe from an engineering standpoint how to do it, I think sonically what he heard in his head, he understood.”

The band would collectively hash out the arrangements through exhaustive rehearsals, but when it came time to record, Corgan laid down the majority of the parts. This oft-talked about procedure became a standard practice.

“As good as D’arcy and James are, it was just going to sound better if Billy played it,” says Vig. “I think it probably caused some friction, but it was something they dealt with and accepted in the band.”

The drums were the one component of the Smashing Pumpkins that Corgan could not reproduce. A jazz drummer by trade, Jimmy Chamberlin paired swing and subtlety with a thunderous intensity reminiscent of legends like Keith Moon and John Bonham.

Chamberlin has been a Yamaha endorsee since 1993, but back then his setup was a Pearl DLX Series kit with a 16x22-inch kick and a Yamaha steel snare. As Chamberlin remembers, the kit was miked with Sennheiser 421s on the toms, Shure SM57s on the snare, an AKG D112/Electro-Voice RE20 combo on the kick, and AKG C414s as overheads.

At the time, Vig didn’t have a tremendous amount of money to make significant cosmetic changes to Smart, but the shape of the studio’s live room, all odd angles and no parallel walls, made for an incredible sound, inspiring the live feel of the band’s studio performance.

Nirvana drummer Chad Channing remembers Kurt Cobain and the 1990 sessions that shaped Nevermind

Gish was recorded onto a two-inch, 24-track Otari MX80, but few things were recorded through the studio’s newly acquired 56-input customized Harrison console (Vig relied largely on outboard Summit and API preamps) though he says that Harrison’s versatile EQ section and exceptional high- and low-pass filters made it easier to quickly carve out pockets in the mix for Corgan’s unique tone. When all was said and done, Gish cost around $20,000 to produce and took just over 30 days to record.

I was over the moon to think I had found a comrade-in-arms who wanted to push me, and who really wanted me to push him

Butch Vig

“For me, that was the equivalent of making a Steely Dan record,” laughs Vig who, two months after wrapping production on Gish, travelled to Los Angeles to record Nirvana’s Nevermind. “Having that luxury to spend hours on a guitar tone or tuning the drums or working on harmonies and textural things... I was over the moon to think I had found a comrade in- arms who wanted to push me, and who really wanted me to push him.”

But for all its sonic ambition, Gish couldn’t hold a candle to what came next. After touring behind their first record, Butch Vig and the Pumpkins spent five months recording their follow-up, Siamese Dream, working 14-hour days, six days a week. And towards the end of the recording process, after tours had been booked and a release date established, they worked a full seven days. Alan Moulder, whose history with dense guitar bands like Ride and My Bloody Valentine, was asked to mix. He booked two weeks at Rumbo Studios in Los Angeles.

Siamese Dream (1993)

We didn’t care if anybody thought it was overproduced

Butch Vig

“When we set out to make Siamese Dream, we wanted to go way, way over the top,” explains Vig. “We didn’t care if anybody thought it was overproduced.”

Tack a zero onto the Gish tab and you come close to matching Siamese Dream’s total cost. Through it all, the tenacity of the group’s work ethic was eclipsed only by the pressure to succeed. Along the way, Iha and Wretzky ended their relationship, Chamberlin developed what would become an acute substance abuse problem, and Corgan’s creative turmoil pushed him to the point of near suicide.

James Iha on his new solo album, guitars and The Smashing Pumpkins

His songwriting, as if voiced by a choleric yet optimistic teenager well beyond his years, hinged on defiance, acceptance, family, and alienation. Of the “hundreds of dumb riffs” they would play, the ones that stuck not only sounded good, they felt good to play.

“I’m a person who tends not to repeat technique, which I guess is kind of suicidal in a way,” says Corgan. “Most people look at a recording career as a series of conclusions. I’ve always treated my recording career more like a journey. I think when an artist gets into a comfortable set of choices, that’s where the death of creativity lies.”

Months of recording meant lots of time for experimentation and tweaking. To help minimise distractions, Vig and the Pumpkins checked into Triclops Studios in Marietta, Georgia, a cosy space that allowed the band a sort of temporary respite. Unlike Smart, Triclops’ ’70s style room had high, woody ceilings that made for a modest decay.

We found a secret weapon on that record

Butch Vig

Vig brought along his API Lunchbox loaded with modular pres for the bass and a few guitar overdubs, but most of the instrumentation was run through the studio’s Neve console onto Studer A800s. Corgan’s “Soul Head” and Marshall cabinet were still in effect, but he no longer used the MP-1. Instead, Corgan achieved Siamese Dream’s highly stylized tone with a litany of DOD pedals and a ’70s-era, silver-faced Big Muff Pi. As the guitar he’d used on Gish had been stolen, his go-to guitars became ’57 Eric Clapton re-issue Strats with Lace Sensor pickups.

“We found a secret weapon on that record,” says Vig. “A little preamp in a pedal steel guitar. It wasn’t built for a loud guitar. It was built for a low output on a pedal steel, so it had this super high-end white noise gain that gave the guitar this sonic jet sound.”

That pedal steel preamp, coupled with an old school tape flanging created by physically speeding up and slowing down the reel by hand is the sound behind Corgan’s otherworldly solo on Cherub Rock. Quiet features hard-panned left and right guitars running through the Big Muff with the tone turned all the way down, while the howling break in the chorus to Mayonnaise is nothing but pure feedback created by Corgan’s $60 pawn shop “Mayonnaise Guitar.”

You can’t have 40 guitars that are all full range – there have to be places for them to fit

Butch Vig

But Corgan’s gear was only part of the equation. The endless overdubs, at least 40 in Soma are well-documented, but Vig says that proper mic configuration is what allowed the parts to congeal. Vig’s mic'ing technique was as follows: Corgan would crank up his amp to full gain, and then set the guitar down. After boosting the headphones send on all the mics, Vig entered the room to move around the mics, using the phase-shifting hiss from Corgan’s guitar echo as his guide. According to Vig, an AKG C 414 produced the widest spectrum of sound, a Sennheiser 421 accented the midrange, and ribbon mics were used to obtain a smoother sound with quick, yet mellow, transients.

“You can’t have 40 guitars that are all full range,” says Vig. “There have to be places for them to fit. You could have low-midrange, or you could have everything scooped out with a high-pass that’s cut at 300 or 400kHz.”

The miking tactic seemed almost drum-like, which, given Vig’s musical expertise, is a fair assumption. “Maybe from me being a drummer, that’s an aesthetic I brought to the table that I didn’t even really understand at the time,” he says.

My voice is really hard to record

Billy Corgan

The army of guitar signals would later make vocal tracking a strenuous procedure for Corgan. Vig didn’t much care for the midrange in Corgan’s voice, so to soften that particular timbre he used a Shure SM7 (generally regarded as a more “open”-sounding mic when its roll off and boost features are engaged simultaneously) through an API preamp and a Summit TLA-100 Tube Limiter, all fed back into Corgan’s headphones. Like everything else, vocal takes were abundant, with Corgan sometimes singing for eight hours at a time to make sure his tracks were pitch-perfect.

“My voice is really hard to record,” says Corgan, smiling. “It’s hard to record, it’s hard to monitor, and it’s hard to mix. I’m Irish, I’m meant to sing sad ballads! My voice isn’t really meant for rock, and I’m pretty sure many people out there would agree with me.”

He laughs again, and you can hear it a little clearer. His voice. That voice, lurking underneath his conversational tone. That unmistakable inflection that can shift from an airy lilt to a nasal, sandpapery growl at the turn of a verse.

To some, it represents instant alternative rock salvation; a vocal uppercut to the face of the status quo. To others, Bruce Britt of the Broward-Palm Beach New Times, for instance, it’s the “most annoying voice in rock.” But Siamese Dream has gone four-times platinum on the strength of that voice because emotionally, it carries with it as much layered complexity and contradiction as the instrumentation that backs it.

“Today” was the greatest day Corgan had ever known, not because it really was, but because it couldn’t get any worse. Somehow that was enough of a comfort to lure him away from the edge. Somehow, against all odds, the Smashing Pumpkins kept moving forward.

“People don’t always articulate their expectations,” says Corgan. “I think whenever we would work with producers, they would do their best to try and balance those forces between what somebody would want, what I would want, and what was best for the record.”

Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness (1995)

Before a single note was recorded, Corgan knew he wanted the next release to be a double album. Flood and Alan Moulder, friends since their early days at the prestigious Trident Studios in London, were tapped to co-produce.

The band began rehearsing at Pumpkinland, their Chicago recording space, and Billy began funnelling cassette demos to Flood for review. Roughly two-thirds of Mellon Collie & the Infinite Sadness was tracked at Pumpkinland on an Otari MTR-90 MKII, while the remaining portion was tracked at the Chicago Recording Company on Studer A820s.

“I love recording at 15 ips NAB, but with Dolby SR, because it just adds a whole different dimension to the sound,” says Flood. “Apart from the obvious benefits of Dolby, if you tweak the Dolby unit really, really well, it’s a bit like adding an Aphex and a dbx sub-harmonic bass enhancer on every channel.

Also, the way that tape changes the sound or modifies the sound, 15 ips is technically not correct, but I find it to be so musical, particularly on the bottom end. This was very much a conscious decision, and very much a part of the album’s sound.”

"A lot of Mellon Collie was tracked by the band at deafening volumes. I mean deafening."

Billy Corgan

Another conscious decision was to change up the manner in which the group recorded. In the past, the band had only used one room to track, which of course meant only one thing could be going on at a time. Hours spent waiting for one person to finish up their part led to frustration.

For Mellon Collie, Flood would generally work with Corgan in the A room on the Otari and an MCI board, while Moulder worked with Wretzky and Iha in the B room on a Pro Tools rig slaved to both Tascam DA-88 digital recorders and two-inch tape.

The combination of analogue and digital opened up a world of recording possibilities and played to the creative strengths of Mellon Collie’s adventurous spirit. A track like Thru The Eyes Of Ruby, which contains approximately 70 guitar tracks, would have been nearly impossible to do with tape alone. Likewise, Porcelina Of The Vast Oceans contains roughly six sections that were all recorded at different times with different instrument and microphone configurations and then fused together, another beneficial byproduct of editing in Pro Tools.

Guitar and amplification choices were the key differences between Siamese and Mellon Collie. For the bass, Wretzky switched up from the P-Bass to a ’60s era Fender Jazz Bass reissue with Ampeg and Mesa/Boogie amps. For Corgan, what sounded great about the Siamese fuzz pedal set up in the studio made it sound horrible live. He still had his Marshall 1960A cabinets, but Corgan shifted to a Mesa Boogie Strategy 500 and a Marshall JMP-1 preamp (Corgan also notes that he used an Alesis 3630 to drive extra gain into a Marshall). As the ultimate goal for Mellon Collie was to capture the band’s live, unbridled sound, Billy largely used this touring rig to record.

“Flood felt like the band he would see live wasn’t really captured on record,” says Corgan. “So a lot of Mellon Collie was tracked by the band at deafening volumes. I mean deafening. There was so much SPL in the room that it was physically uncomfortable. Your ears, your emotional resistance, would wear down.”

Flood also discovered that Corgan was a much better singer pitch-wise when he didn’t use headphones, so he switched Corgan up to a Shure SM58 and had him sing in front of open speakers.

“My experience with U2 taught me that a lot of things you’d expect to become problematic with monitors in the room aren’t, and by careful use of screening, by positioning the monitors and what you put in the monitors you can actually get a lot of benefits,” says Flood.

We also developed this system whereby we had what was called ‘rehearsal mode’ and ‘tape mode’

Flood

“For instance, Jimmy used to love having the kick drum and a bit of snare going through his wedges, which were directly behind him. So if you’ve got a kit that’s lacking a bit of bottom end, you pump the kick and the snare through the wedges and you start to tweak them to get extra weight.

"We also developed this system whereby we had what was called ‘rehearsal mode’ and ‘tape mode.’ In rehearsal mode, everybody was on the floor, the amps were blaring, and you wouldn’t have to worry about spills. We had the speakers inside these big coffin flight cases in the back of the room and mic'd them close up, then mic'd them about six feet away. Then we’d close the lid. When you were tracking in tape mode, everybody could flick over at the flick of a footswitch and their amps would be quietly purring away in the corner. When you’d give a little bit back to them in their own respective monitors, automatically the sound of the room cut right back and you’d get the vibe of four people playing on top of each other.”

For the drums, Chamberlin’s core Mellon Collie kit was a Yamaha Maple Custom with a 16x22-inch kick, a 22-inch ride, 18-inch and 19-inch Zildjian A Custom crashes, 22-inch swish knockers, and 10-inch and 15-inch fast crashes. Because of his big band background, he frequently changed out his snares, building his kit around the snare and the ride as opposed to the kick. The familiar drum rolls all throughout “Tonight, Tonight” can be attributed to Jimmy’s classic 5 1/2x14- inch Ludwig Supra-Phonic.

“From there I go to microphones as far as how I want the drums to sit dimensionally in the track,” Chamberlin informs. “If I want the drums upfront and aggressive, I’ll use a lot of AKG C 414s so they sit in front of things dimensionally. If I want the drums to sit in a rhythm section configuration, I’ll lean back towards the 414s and maybe some Shure SM98s. Then maybe go for Shure 12As on the bigger drums.”

Mellon Collie debuted at No.1 on the Billboard 200 when it was released in October of 1995. Less than a year later it had crested $6 million in sales and was later nominated for seven Grammys. It was the most powerful statement the Smashing Pumpkins had made to date. Unfortunately, much-publicized events that took place during the group’s 1996 tour produced an equally powerful effect.

"Blank page is all the rage. Never meant to say anything."

Blank Page (1998)

Death, divorce, and harsh life realizations “that have only recently probably finished playing out,” says Corgan, clouded the two years after Mellon Collie’s release. By the time Corgan saddled down to write Adore, Iha was focusing on his solo album (Let It Come Down), Wretzky was a sporadic presence, and Chamberlin was out of the band. Filter’s Matt Walker was brought in to replace Chamberlin for the remainder of their tour, but the hole left by the original drummer’s absence would significantly impact the creation of the new record.

“I thought I was going to do this really different album,” says Corgan. “So typical me, I didn’t use any of my gear. Like, any. I went out and bought new guitars and strange amps, a Fender Blackface and a Selmer combo, I think. Most of my memories with Adore have more to do with programming.”

Adore (1995)

The success of Eye, an industrial hip-hop crossover track that appeared on the soundtrack to David Lynch’s Lost Highway instilled much-needed confidence in Corgan. It was basic electronic production, but it proved to him that he could press on with more sophisticated fare. Corgan hooked up with Brad Wood (Liz Phair, Placebo) and began recording with the band in Chicago during the summer of 1997. Never one to do anything the easy way, Corgan decided to load into a new studio nearly every week. It was catch-as-catch-can recording. If something wasn’t working in a new surrounding or couldn’t get set up in time, it wasn’t used.

“He was trying to create a different environment, quickly and geographically, and trying to avoid certain things that happen when a band settles into a studio,” says Bjorn Thorsrud, who has engineered every Pumpkins record since Adore.

“I did go around and proclaim rock to be dead, which was probably the stupidest thing I ever did."

Billy Corgan

The material was recorded on a mix of analogue and digital formats. Already familiar with Studio Vision Pro for MIDI and audio editing, Corgan used ReCycle to chop up and manipulate drum loops. A Kurzweil K2500 and an Alesis HR-16, the same drum machine used to create the beat for 1979, were also used for additional rhythmic elements and sequences. Wood’s classic EMS VCS3 “Putney” was featured prominently on Ava Adore.

As it was with Mellon Collie, experimentation was paramount. Boxes would show up in the post every other day, each one containing a new sample library, vintage synth, or rack module gobbled up from eBay or plucked from the pages of Keyboard magazine. Still, the pieces weren’t fitting together and, eventually, Corgan and Wood parted ways.

Billy Corgan on recording The Smashing Pumpkins' Monuments To An Elegy

“It was a total crapshoot,” says Corgan, who soon relocated to L.A. to refocus his energy. “I was out of depth. There was no process, there was no system, and there was no go-to piece of gear. There was nothing. I learned a tremendous amount, but I couldn’t tell you what the hell I did.”

Billy reached out to Nitzer Ebb’s Bon Harris, who contributed additional programming and sound design with the aid of his Nord Modular, Oberheim Xpander, and massive Roland System 100M. But the songs didn’t come into full focus until Corgan reconnected with Flood, whose experience with bands like Depeche Mode and Nine Inch Nails made him the perfect candidate to help actualize Adore’s hybrid vision.

The dissonance was evident to Flood upon arrival. The mix of disparate Pro Tools sessions and one-inch tape created a textured canvas that proved difficult to homogenize, and the tension between band members was palpable. The band worked at Sunset Sound until reoccurring technical difficulties with the Neve console forced them to complete the project at the Village Recorder in Santa Monica. To further Adore’s maudlin, Goth-tech spirit, Corgan assumed a Max Schreck-like persona, emphasizing his shaved head with lighting and make-up and donning long, flowing garb that accented his 6-foot 4-inch frame.

I did go around and proclaim rock to be dead, which was probably the stupidest thing I ever did

Billy Corgan

“I did go around and proclaim rock to be dead,” Corgan laughs, “which was probably the stupidest thing I ever did. I was in my Adore personality saying things like ‘Fuck the electric guitar!’ And of course, 12 months later I’m playing The Everlasting Gaze.”

Many fans attributed Adore’s stylistic shift directly to Chamberlin’s lack of participation, and contrary to favourable reviews and another Grammy nomination for Best Alternative Music Album, Corgan insists “nobody got the record.” “To Sheila” pumped blood through its mechanized heart, “Ava Adore” flashed her crooked teeth, but the bite wasn’t as strong. Chamberlin’s raw power was replaced by reverberating, distorted 808 kicks. Shuffle and swing turned into quantized grooves and fills. Predictable ticks marched along in place of glittering cymbal embellishments.

“I don’t feel excluded from Adore,” says Chamberlin. “When I listen to that record, I hear decisions that I totally influenced because I wasn’t there.”

Machina / The Machines Of God (2000)

"You know I’m not dead. I’m just living in my head."

The Everlasting Gaze (1999)

Chamberlin returned to the Smashing Pumpkins in March of 1999, but another absence would alter the face of the band’s fifth studio release, Machina/The Machines of God. Flood was once again asked to produce, but unlike Mellon Collie, where many ideas were mapped out before a single note was recorded, few were aware of Corgan’s creative intent: a concept album about a fictitious rock band fronted by a character whose life is forever altered after hearing the voice of God. As could be expected, the sonic subtext would prove just as esoteric.

The goal was to take the digital lessons learned from Adore and apply them to a rock environment. How does one create the sound of a band playing on another planet? Through tape degradation, synth-like mechanized guitars, soaring pads and effects, heavily-processed vocals, and of course, big drums.

Chamberlin returned with a custom-made Yamaha green maple kit, but Machina marked Corgan’s first real departure from his fleet of Fenders, instead using a Les Paul Junior reissue with P90 pickups that often ran through a Crate practice amp. An SIB Varidrive and a host of Moogerfooger pedals were also used to add to Corgan’s sonic repertoire. The hazy shimmer in big choruses for Stand Inside Your Love and The Everlasting Gaze is another trademark Machina sound.

“I hope I’m not taking credit for somebody else’s work,” laughs Alan Moulder, “but I’m pretty sure I created it with a tape delay on a short, slappy guitar reverb going through an AMS Harmonizer. I think I ducked it with compression triggering off the drums.”

To help the band gel with the new material, Corgan decided to take the Pumpkins out for a few select club dates in April of ’99 while Flood went on holiday. They would return to the studio fine-tuned, ride that live momentum through a weeklong recording session, and then bring in Moulder to mix after another head-clearing break. When Wretzky’s commitment to the band began to erode, plans began to change. Though rumoured since late summer, it was publicly announced in September that she had left the band.

“Billy and I thought, ‘How are we going to do this?’” Flood remembers. “We decided that we were going to have to make a very different kind of record. They saw out their time on the tour, and after that we pretty much went back to the drawing board. Certain songs on the record are survivors from that first period, but it meant a shift in the way the songs had to be formed.”

The majority of the songs were recorded into Pro Tools through Corgan’s API Legacy board, but the band had multiple mixing consoles to choose from at Chicago Recording Company, so Flood performed a litmus test. He transferred two songs onto tape using a Studer A280, which as luck would have it, was found in each of the mix rooms. He then ran the tape through each console with all the faders at zero, no EQ, no panning and then into a DAT machine. When he compared the recordings, the differences were unbelievable.

Of the Neve VR72, SSL 6056E, and the ’80s Neve broadcast console that Corgan brought in, the SSL won out. Its low-mid punch would help tighten up the record’s bright sound. Though Corgan wasn’t a big fan of SSL boards, the team found a workaround.

“Howard Willing, one of the mix engineers, knew a guy at Inward Connections who built an API simulation mix bus,” remembers Moulder. “The idea was that we were going to replace the mix bus in the SSL with this API one, which kind of ‘de-SSL’d’ it a bit.”

Machina was made with the understanding that it would be the Pumpkins’ final album. Machina II/The Friends & Enemies of Modern Music, originally intended to be the second disc on a Machina double album before Virgin vetoed the idea received an internet-only release, but a handful of copies were distributed on vinyl through Corgan’s own imprint: the befittingly titled Constantinople Records.

"Erase the schemes that I’m drawn to believe. There’s no fear anymore."

Sunkissed (2008)

Zeitgeist (2007)

I know a lot of our fans are puzzled by Zeitgeist

Billy Corgan

“I know a lot of our fans are puzzled by Zeitgeist,” admits Corgan. “I think they wanted this massive, grandiose work, but you don’t just roll out of bed after seven years without a functioning band and go back to doing that.”

A few key decisions had already been made before Corgan and Chamberlin set out to record Zeitgeist. Thematically, the record was going to bear down on the country’s sordid sociopolitical state, and blunt force analogue production would galvanize the ship. Furthermore, Corgan penned Zeitgeist knowing his new band members would be both qualified players and singers, which allowed him to expand the scope of his vocal parts.

We were working purely on intuition as to what the overall sound should be”

Roy Thomas Baker

Corgan and Chamberlin began demo-ing at a rented space in Arizona before moving to Kerry Brown’s studio in Los Angeles for further fleshing out. Though initial work began with Michael Beinhorn (Korn, Black Label Society), Roy Thomas Baker became the album’s primary producer.

“We were working purely on intuition as to what the overall sound should be,” says Baker, whose long list of production credits includes Queen’s A Night At The Opera. “It was supposed to be an analogue sound, but it wasn’t supposed to be old school. If you’re doing everything intuitively, there’s no such thing as old and new school. We were going for an audio uniqueness as opposed to sonic purity.”

Corgan’s new guitar rigs included Diezel Herbert and Einstein heads (the latter for overdubs) and a Bogner Uberschall, again run through his classic Marshall cabinet. He also began experimenting with different model Fenders in preparation for the release of his signature model Strat, but, as Baker recalls, “there were more guitars in the studio than at Guitar Center.” Recording at The Village on both a new Neve 88R console and a vintage Neve 8048, the goal was to capture the impenetrable truth of a live, organic performance.

Jimmy is probably one of the most unique drummers I’ve ever worked with. Even when he does something he considers bad, it’s still better than 98% of the people out there at their best”

Roy Thomas Baker

As Corgan isn’t generally a punch-in player, all the guitar parts had to be replayed from the top down, which at times put both Billy and Jimmy in even more visceral situations. Drums for the nearly ten-minute epic “United States” were recorded in one take.

“Jimmy is probably one of the most unique drummers I’ve ever worked with,” says Baker. “Even when he does something he considers bad, it’s still better than 98% of the people out there at their best.”

The drums were recorded in Studio A at Los Angeles’ Sage and Sound, a spacious room with 18-foot ceilings and a fully restored Neve 8048 console. The drum and overhead mic configurations didn’t change much from the Gish days, but the room was miked with an AKG C24. Chamberlin also switched to his now-favourite crash, a lush, dark 22-inch Zildjian Constantinople and downsized his kick from a 16x22-inch to a 14x22-inch to obtain more resonance and a different shell sound. Another tactic he used to employ fuller sound in his drums was to customise the bearing edges to 60 degrees instead of 45, which Chamberlin says pushes the sound around the drum instead up back to the drummer.

“Roy was the only guy that really noticed that phase cancellation,” laughs Chamberlin. “That guy hears things that nobody else hears! I learned more with Roy Thomas Baker in those four or five months than I have ever learned in my entire recording career.”

In addition to Baker, former Pantera and Soundgarden producer Terry Date assisted in the final stages of production. For Corgan, Dates’ straightforward approach to the songs “helped them resonate on a physical level,” and was a good foil for Corgan’s complex methodology. Mixing was also a very absolute process.

“Everything had sort of an on/off switch,” explains Baker. “So instead of having various degrees of volumes, we’d have the approach of, ‘It’s either on or it’s not.’ Billy would say things like, ‘I can hear it, but it should either be a lot louder, or a lot quieter.’”

Everything got progressively louder and louder

Corgan, Chamberlin, and Baker took their methods even further during the mixing of the American Gothic EP. “We did everything by hand . . . multiple hands,” laughs Baker. “I was sitting on one end and Billy and Bjorn [Thorsrud] were on the other. Jimmy was maybe standing back and listening to the overall mix, leaning forward and turning something on—and everyone had different faders. Everything got progressively louder and louder, it was like a race to see who could reach peak volume the fastest! We had a good laugh doing that.”

Jeff Schroeder: "The Smashing Pumpkins guitar sound is very unique in terms of what’s required

The four-song American Gothic represents some of the Pumpkins’ best and most exciting material to date. It also signals a potentially new style of “bite-sized” recording that seems to fit with Corgan and Chamberlin’s current creative mindset: smaller packages, single producers, streamlined concepts. Corgan isn’t one to force the issue these days, and now that the Pumpkins no longer report to a label, anything goes.

“I know the next record is going to be really psychedelic,” says Corgan. “I don’t think the Sabbath influence is going away anytime soon, but I’m thinking more late ’80s/early ’90s English shoegazer mixed with ’60s psychedelia and ’70s funk. I can hear it in my head, but that doesn’t mean it’ll ever get out of my head.”

Fans can expect a Smashing Pumpkins 20th Anniversary Tour sometime in late 2008, as well as the Fillmore live DVD release. But spring of 2009 is when things should get really interesting. As this article is being written, SmashingPumpkins.com is petitioning fans for original photos from 1987–1992 in preparation for the release of a Gish box set, which may include everything from demos and B-sides to revisited versions of old songs.

The group also has archived performances of their first 40 shows, warts and all. As they have no label contract in place, the size of the box set is to be determined, which is good news for superfans, as Corgan is no stranger to releasing Herculean sets of material.

The Pumpkins will also embark on a small-scale tour to support the release, which means Gish songs, Gish gear, and intimate Gish-sized venues. Need more message board fodder? Corgan plans to give each and every Pumpkins album the same treatment. Does all this historical activity signal a break in fresh songwriting? Not a chance.

“Look, we hit massive homeruns. We never followed them up. We never took the safe, obvious next step"

Billy Corgan

“This should now be where I prove what I’ve always felt I’m capable of,” says Corgan. “There’s nobody in my way, there’s no MTV not playing my video, there’s no gatekeeper. If I can truly do phenomenal work, it will be heard, whether it’s acquired for free or bought, it doesn’t make any difference. There’s nothing standing between me and an audience.

“Look, we hit massive homeruns,” he continues. “We never followed them up. We never took the safe, obvious next step, and I think that gets lost. We’re not a milk-it band. We never were a milk-it band. There’s that old saying, ‘If it’s on the cover of Time, it’s too late.’ By the time people got around to understanding what we were doing, we were gone. Now is the time to prove our mettle.”

Age Of Innocence: An 11-song journey through the Pumpkins' underrated catalogue

1. Tristessa (Gish)

Palm muted guitar chunks, extreme snare rolls, and a mellow break followed by a blistering solo, Tristessa is every trademark Pumpkins embellishment rolled into one track.

Producer Butch Vig utilized light compression through a combination of Summit and API compressors to preserve headroom and accommodate the song’s extreme dynamics, but Corgan’s Gish-era, attack-style guitar still cuts through the mix like a blade.

2. Starla (b-side from the I Am One single)

An epic, mesmerizing track built up around extended solos, Starla was produced by Kerry Brown and recorded through a Soundcraft TS12 board onto a TASCAM MS16 one-inch tape machine. Brown used a Yamaha SPX90 for the reverb effect on Corgan’s voice, and an Eventide H3000 Ultra-Harmonizer is responsible for the backwards effect that runs through the first third of the song.

“I remember that overdub guitar solo,” says Brown. “Just him, the headphones, and the cabinet. You don’t hear that much anymore. You can’t simulate what you can do with a cabinet in front of you. I mean, Billy was bending notes on a mic stand!”

3. Glynis (No Alternative compilation)

Though it’s rarely played live, Glynis is one of the Pumpkins’ finest non-album tracks, and can only (officially) be found on the 1993 No Alternative compilation.

An old Speak & Spell “hello” starts the song, and the soupy solo in the middle is the result of double-tracked guitars fed through a vintage Electro- Harmonix Bassballs pedal. The song is a dedication to former Red Red Meat bassist Glynis Johnson, who passed away from AIDS-related complications in 1992.

4. Beautiful (Mellon Collie & the Infinite Sadness)

A result of digital/analogue synergy, Beautiful is a processional ballad featuring opening and closing orchestral-style arrangements created via MIDI. Corgan handpicked sounds that fit with the song’s psychedelic vibe, and then jammed to the track in MIDI, adding and removing notes as he went along.

“There’s something about that visual connection to my brain that’s really good for me in terms of writing,” says Corgan. “But let me say this,” he continues with a laugh, “can we please get off MIDI? When you’re a guitar player, you plug it in. It works; it doesn’t work. If it’s the pedal, you change the battery. But then you’re sitting in front of a computer and you get that spinning wheel of death. . . .”

5. Eye (Lost Highway soundtrack)

Most people know Eye as the electro-rock crossover from the popular David Lynch film, but the track began as an instrumental for Shaquille O’Neal. The two were linked up by a longtime friend of Corgan’s. Being a big sports fan, Corgan was up for the challenge.

He concocted the instrumental before speaking with Shaq, but the two weren’t able to meet up to seal the deal. Lynch, on the other hand, thought it was perfect for Lost Highway. The track relied heavily on a Kurzweil K2500 for its 808-styled percussion, a Waldorf VST for the synth line, and a 12-string acoustic lined in direct.

6. Blissed & Gone (Still Becoming Apart promo)

With radio samples and distorted percussion sliced and diced in Propellerheads’ ReCycle, Blissed & Gone is another product of Corgan’s Adore-era experimentation with loops and samples. “I remember playing the song for Rick Rubin when he came to visit me in the studio, and he didn’t know what to say,” Corgan remembers. “That’s the trip I was on.”

7. Untitled (Rotten Apples)

The final track recorded by the original Smashing Pumpkins line-up in 2000, Untitled was semi-acoustic home cooking that rekindled the vibes of Gish and Siamese Dream.

"The song was our way of saying ‘f**k you’ to all those people who thought we’d somehow lost our minds and weren’t able to return home"

Billy Corgan

The chain for Corgan’s solo, one of his favourites, features a DOD FX84 Milk Box compressor and a Shin-Ei Companion Fuzz Wah. “The song was our way of saying ‘f**k you’ to all those people who thought we’d somehow lost our minds and weren’t able to return home,” says Corgan. “We were in the studio for what appeared to be the last time, so it was very emotional, and we had only three days.”

8. The Everlasting Gaze (Machina/The Machines of God)

The Everlasting Gaze is the first track off Machina, a highly conceptual piece that marked the return of Chamberlin, but whose course was altered by the departure of Wretzky halfway through recording. The shiny, cosmic grunge that defines the album is encapsulated in this four-minute juggernaut.

Corgan switched up to a Les Paul Junior ’57 reissue with P90 pickups, but the extra crunch came by running it through a little Crate practice amp, then going direct into the box from the amp’s line out jack. “When we really wanted to ‘go there’ we would plug into the headphone jack,” laughs Corgan.

9. Pomp & Circumstances (Zeitgeist)

When Danny Elfman had to bow out amicably of doing the string arrangement, Corgan opted to forego their second option for an internal fix. Using an E-mu Emulator II, they built up a shredded wall of sound that was then bounced down and tape degraded numerous times until it was virtually falling apart at the seams.

The tonal disparity between the 8-bit E-mu (although it used a data compression algorithm that gave the equivalent of at least 12 bits), an inspired, bluesy solo, and Corgan’s soaring vocals, doubled nearly 30 times in true Roy Thomas Baker fashion give the song its uniquely operatic feel.

10. Again, Again, Again (The Crux) (American Gothic EP)

Another product of the Pumpkins’ tenure with Roy Thomas Baker. The exceptionally loud Gibson J-160E acoustic had such a distinctive punch in the lower midrange that it was paramount to pair it up with an electric that didn’t overshadow the tone.

The solution: A 1973 Telecaster run through a ’60s Selmer amp and double-tracked. If Zeitgeist is the sound of a world pounded into dust, American Gothic is the sound of that world waking up to a new era of possibility.

11. Superchrist (Fresh Cuts, Volume 2)

Superchrist pairs the Pumpkins with longtime friend and producer Kerry Brown (Starla) for a 6/8 psychedelic jam. A custom API console in Studio 3 at Sunset Sound was used for tracking, with a fair amount of trial-and-error determining which instruments sounded best on what channel.

With 18 analogue drum tracks thrown against the well-worn tone of a 1958 Fender P-Bass (run through an Ampeg SVT-VR head with an SVT- 810E cabinet and miked with an AKG D12), “ballsy” doesn’t even come close to describing the sound.

Electronic Musician magazine is the ultimate resource for musicians who want to make better music, in the studio or onstage. In each and every issue it surveys all aspects of music production - performance, recording, and technology, from studio to stage and offers product news and reviews on the latest equipment and services. Plus, get in-depth tips & techniques, gear reviews, and insights from today’s top artists!

“It is ingrained with my artwork, an art piece that I had done years ago called Sunburst”: Serj Tankian and the Gibson Custom Shop team up for limited edition signature Foundations Les Paul Modern

“The last thing Billy and I wanted to do was retread and say, ‘Hey, let’s do another Rebel Yell.’ We’ve already done that”: Guitar hero Steve Stevens lifts the lid on the new Billy Idol album