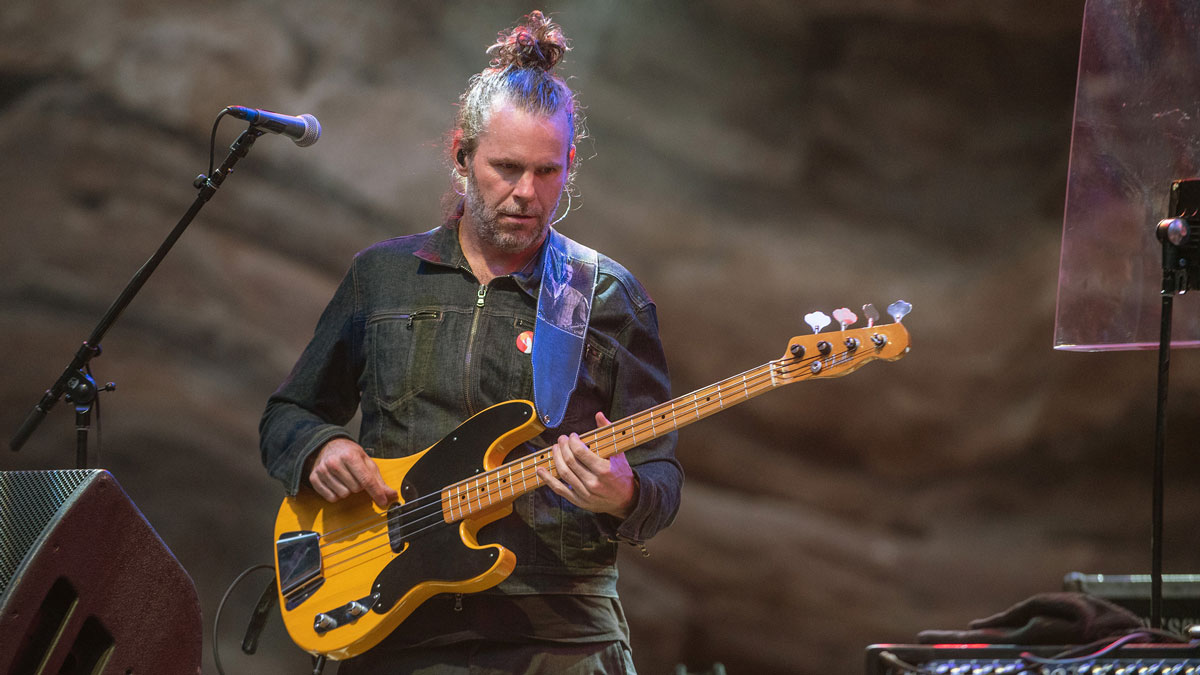

Session bass ace Tim Lefebvre: "Even if it’s obtuse harmonically, if it’s funky, people will respond to it"

Tedeschi Trucks, David Bowie and Brian Adams bassist on improvisation, gear and Whose Hat Is This?

Bassist Tim Lefebvre may only be half-joking when he says, “If you have a free minute, you’re not working hard enough.”

When he’s not playing bass with the Tedeschi Trucks Band, he and TTB bandmates Tyler Greenwell, JJ Johnson, and Kebbi Williams are gigging and recording as Whose Hat Is This? Their second album, Everything’s OK (Featuring Kokayi), was released in November 2018.

Lefebvre is a top-call session and touring musician: Sting, John Mayer, Donny McCaslin, Donald Fagen, Elvis Costello, Oz Noy, and Wayne Krantz are but a few of the names on his resume, that’s his bass work on David Bowie’s Blackstar, and he has an ongoing list of soundtrack work for television and film.

Recently, he added 'producer' to his credits with wife Rachel Eckroth’s latest album, When It Falls, and North Carolina band The Broadcast’s Lost My Sight, co-produced with TTB/Whose Hat’s Tyler Greenwell. So, “every moment must be taken up” isn’t really a stretch, even though he’s laughing when he offers the observation.

Now based in Los Angeles, Lefebvre grew up in Massachusetts, where he played saxophone in his middle school band. He took up guitar - actually his sister’s guitar - and woodshedded to AC/DC, Rush, and Van Halen records. In high school, he began playing upright bass.

He attended college, double-majored in political science and economics, and took that degree to a gig playing bass on a cruise ship. From there, at the encouragement of a colleague, he moved to New York and began playing with Wayne Krantz, a musical education that he still draws on in his current projects.

The gear list on your website reads like an encyclopedia. With so much at your fingertips, do you still gravitate toward specific pieces of gear, no matter what?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

With Tedeschi Trucks, I drop some occasional octave bombs, but other than that, it’s more play the bass straight down the pike

“That’s the case a lot of the time. It depends on what kind of gig I’m doing, but if I’m doing creative stuff, I try to have a bunch of distortions, octave pedals, delays, something to mess up the signal so it can make weird sounds. When it’s just a play date, I bring an octave [Note: Lefebvre has a signature Octabvre from 3Leaf Audio] and distortion and that’s it, and I might not even use it.

“There are some gigs where you have to be more conservative with that stuff because it’s not the right thing. I’m always trying to serve instead of dictate. I think that’s a good rule to stick to.

“With Tedeschi Trucks, for instance, I drop some occasional octave bombs, but other than that, it’s more play the bass straight down the pike. With Whose Hat Is This? I have to generate more interest from the bass and make sonic and harmonic stuff happen, so it behooves me to have more sounds available.”

When did you learn to play for the song?

“The biggest person who influenced me on that was Darryl Jones. I was a big fan going back to Miles Davis’ Decoy, but then all of a sudden I one day woke up and he was playing with Sting on Dream Of The Blue Turtles, and I thought, 'This guy can wear a bunch of hats.'

“I listened to what his intention was when he was playing, and I listened closely. He’s one of my heroes, so I checked that out really hard, how he was playing songs. He was picking his moments to generate interest from the bass, but most of the time he was just playing the song, playing it simple, making the notes ring out, and you could clearly hear what he was doing, so that had a major impact on me.

“Before that, there was Paul McCartney and all the regular guys, but for some reason Darryl Jones just hit me over the head with it. From there, I was always trying to sound like Darryl Jones - and that’s a whole other topic of not trying to sound like anybody, but honestly, I was trying to sound like Darryl Jones. It’s your own filter, so it comes out sounding your own way, but that’s never been one of my things, having your own sound. It just happened by trying to imitate other sounds.”

When did it happen for you?

“When I moved to New York, I started playing with Wayne Krantz, and he wanted me to avoid trying to play Paul Jackson and James Jamerson licks, so I took that on as a task. Trying to remain creative without sounding directly like somebody else is something that just kind of happened, and it happened in a trio form. It wasn’t me practising that stuff. It happened playing with two other people, so it was fun learning it that way because it’s more organic.”

Did playing in a trio, versus a full band, fuel your innovation and chops in a different way?

I learned so much from playing with Wayne Krantz. Rhythmically, harmonically, it was always an experiment

“Definitely it did. I learned so much from playing with Wayne Krantz. Rhythmically, harmonically, it was always an experiment, and doing it in a trio form, you do have to fill up more sonic space. Again, it’s a matter of keeping the music moving forward and generating interest.

“So that was a huge learning experience. And we were playing together all the time. For four or five years straight I was with that band and almost doing that exclusively, so that’s where a lot of that formative stuff came from. Of course, half the time I was trying to sound like Darryl Jones!

“There were other influences creeping in, of course, but for a long time that was the main place I was coming from, and eventually it took on a life of its own. But everybody did. Keith Carlock turned into a juggernaut, Wayne Krantz obviously has his own sound, so we really all found our sound there and it was fun to do.”

Are those foundations present in what you do now?

“It’s always there. The rhythmic toolbox we developed as a trio will always stay with me because we got pretty deep. Always in 4/4 and always in eight-bar phrases, but the way we could twist the beat around - that’s a calling card for me at this point, just having gone so deep with those guys on the rhythm stuff. It was nothing obvious; we were all just in our minds, the phrases and the time were going by in our heads and we weren’t necessarily playing it obviously.

“I think that’s one of the ways I help Tedeschi Trucks move forward, because I wasn’t coming from a - God bless them - James Jamerson or George Porter place. There’s a little bit of that in there, but mostly I’m doing rhythmic and harmonic stuff that’s out of the Wayne Krantz bag that I think has helped propel how the solos and improvs in that band have gone down, so it became very useful for that.”

What is practice like for you?

“The practice on upright is going to come back. I’ve been on the road so much the last couple of years with Tedeschi Trucks, and we used to have an acoustic bass out there with us, so right now I consider myself to be rusty. But as I develop more time, I’m going to get back into it.

“So upright I have to practise. That’s a beast of an instrument. I don’t think anybody can get away with not practicing it. It’s physically so demanding and there’s so much technique to it, it’s kind of an endless search of figuring out how to play the instrument.

“With electric, I improvise by myself to keep my chops fresh and build up stamina, and some of the practice comes from learning people’s music. If I’m playing with somebody, which is pretty often, I need to learn their songs.

Part of the practice I do is I figure out how to use effects, like generating some sonic stuff. It’s all a big search

“Also, part of the practice I do is I figure out how to use effects, like generating some sonic stuff. It’s all a big search. But technically, on electric bass, I like to keep it as unorthodox as I can, whereas with upright, you can’t get away with that. There’s no way.”

While the rest of the world has turned to modeling, you’re still schlepping an Ampeg SVT. Your crew must love you.

“Yeah, that’s my thing! When I’m just gigging in LA, I just use 2x10 cabinets, and I got some really nice amps from Darkglass Electronics, these vintage Microtube amps. They’re tiny and sound incredible, so I’ve been using those a little bit live. They’re great. It cuts down the load.”

How important is reading? Some musicians believe that studying music and reading charts expands your horizons, while some believe that it stifles creativity because you learn to play by the rules.

“I think both have their positives and negatives. The world’s changing a little bit right now, so I don’t think it’s as important that you’re an amazing reader, because first of all, opportunities for things like film scores seem to be less, which is where that stuff came into play.

“Also, when people do records now, like songwriter stuff, sketching out a general chart, like a chord sheet, and then learning the rest by ear has become more my speed, unless I have to learn something really quick and it’s really complicated.

“Both things come in handy, but you don’t necessarily need one or the other. If you’re in the studio all the time, learning by ear is not going to be necessary, but I feel it’s good to have both. I’ve been doing more ear stuff lately instead of writing out charts, or in-depth charts, so it’s always a blend.”

Do you bring pieces of each project into the next, if not obviously, then at least in subtle ways?

“I think that always happens, whether you know it or not. I went from a Tedeschi Trucks tour to a Bryan Adams tour, and then right back to Tedeschi Trucks, so it was going from one thing where I can be creative and messy and play stuff differently every night, and then Bryan Adams was straight-up play the parts every night, so that was a learning experience.

When I got back to Tedeschi Trucks after the Bryan Adams tour, I was playing things a lot more simply, and Derek was like, 'Come on, man, play more'

“When I got back to Tedeschi Trucks after the Bryan Adams tour, I was playing things a lot more simply because that’s what Bryan Adams wanted, and Derek was like, 'Come on, man, play more.' It definitely was informative, but I couldn’t unplug from it immediately because it was so close that each tour ran into each other.

“When we’re soundchecking, I have my delay pedals on, making trippy, dark-sounding things that I record and then take home and see if I can do anything with them. So there’s always stuff coming in and out just in general.

“If I’ve been listening to John Coltrane’s Interstellar Space, or something like that, and we start playing a free jazz jam in Tedeschi Trucks, which happens, all of a sudden I’m coming from whatever space that’s in my subconscious. It’s not something you can plan on and know, like, 'Oh yeah, this is this and that is that.' It just happens and you let it flow. And if it’s wrong, somebody will tell you it’s wrong!”

Whose Hat Is This? is, in fact, part of the Tedeshi Trucks Band, which brings us back to one project informing the next.

“Absolutely. That is 100 per cent true. One does inform the other. This is only my opinion, but I think when we go from a Whose Hat tour into a Tedeschi Trucks tour, we’re playing looser and fresher and our chops are up, so I think it only helps.

“Derek likes to plays dynamically - he’s great at directing the band that way - so sometimes we get into something that’s really quiet and we stay quiet. So the dynamic thing of Tedeschi Trucks definitely always stays with us. It’s fun.”

How do you keep free jazz from becoming, 'What is this, where’s the exit ramp, and how do we reel ourselves back in?' And with that, how do you keep from losing the audience, especially the non-musician members of the audience?

“Oh yeah, it’s challenging enough to hear that stuff. I try to keep it groovy. I don’t think you can sit there all night just going and going and going. For me, rhythmically, there has to be some kind of… even if it’s obtuse harmonically, if it’s sort of funky, people will respond to it.

“That’s the idea behind the new record with did with Kokayi. He hooked up with the funk side of what we do, or he just started doing stuff that made us play funky, which was incredible. I could sing his praises all day, because we were just doing our thing and he made songs out of it, which is pretty incredible to me.

It’s entertaining free jazz! I don’t think we’ve ever had to pull the alarm on anybody being self-indulgent in this band

“There’s got to be some of that, there’s no doubt. If you watch what we’re doing, there’s visual stuff to it that happens that keeps the interest. It’s not like we’re just standing up there looking at people and playing weird stuff at them. We’re really good at engaging the audience. There’s a human touch to it that people can relate to. It’s not just four old men playing free jazz at people and hoping they like it!

“I know it’s a hard listen. Some of our initial fanbase were Tedeschi Trucks fans and they were like, 'I’m not sure if I like this or not,' and probably most of them don’t, but a lot of them do because they know us and we’re delivering some kind of entertainment thing that’s cool to them.

“It’s entertaining free jazz! I don’t think we’ve ever had to pull the alarm on anybody being self-indulgent in this band. When we’re onstage, it’s all music, and everybody’s concentrating really hard and giving, so it’s cool.”

Do you have some parting words of wisdom for surviving the current landscape of the music industry?

It’s a slog sometimes and you have to hang in there. That’s the hard part, because there’s a lot of stuff that will try your patience and try your will

“It requires a lot of patience and a lot of hanging in there. Especially nowadays, it’s pretty daunting to be a professional musician, so a lot of people have other jobs. It is hard.

“Records don’t pay anything anymore because nobody’s paying for music, so that’s eliminated that one income stream, and even if you’re recording a lot, people are paying less for recordings. But if you really love it and you have some patience and you can survive, then you’ll be better off for it.

“It’s a slog sometimes and you have to hang in there. That’s the hard part, because there’s a lot of stuff that will try your patience and try your will. It’s difficult, but always keep the big picture of what you’re trying to do in mind.

“You have to say yes to a lot of stuff that maybe you don’t need to say yes to in your mind, but you do need to say yes to everything you can for a period of time, because things just happen and you never know who’s going to call you based on that $25 gig you did at a bookstore. Everything leads to something, and that’s the game you’ve got to play.”