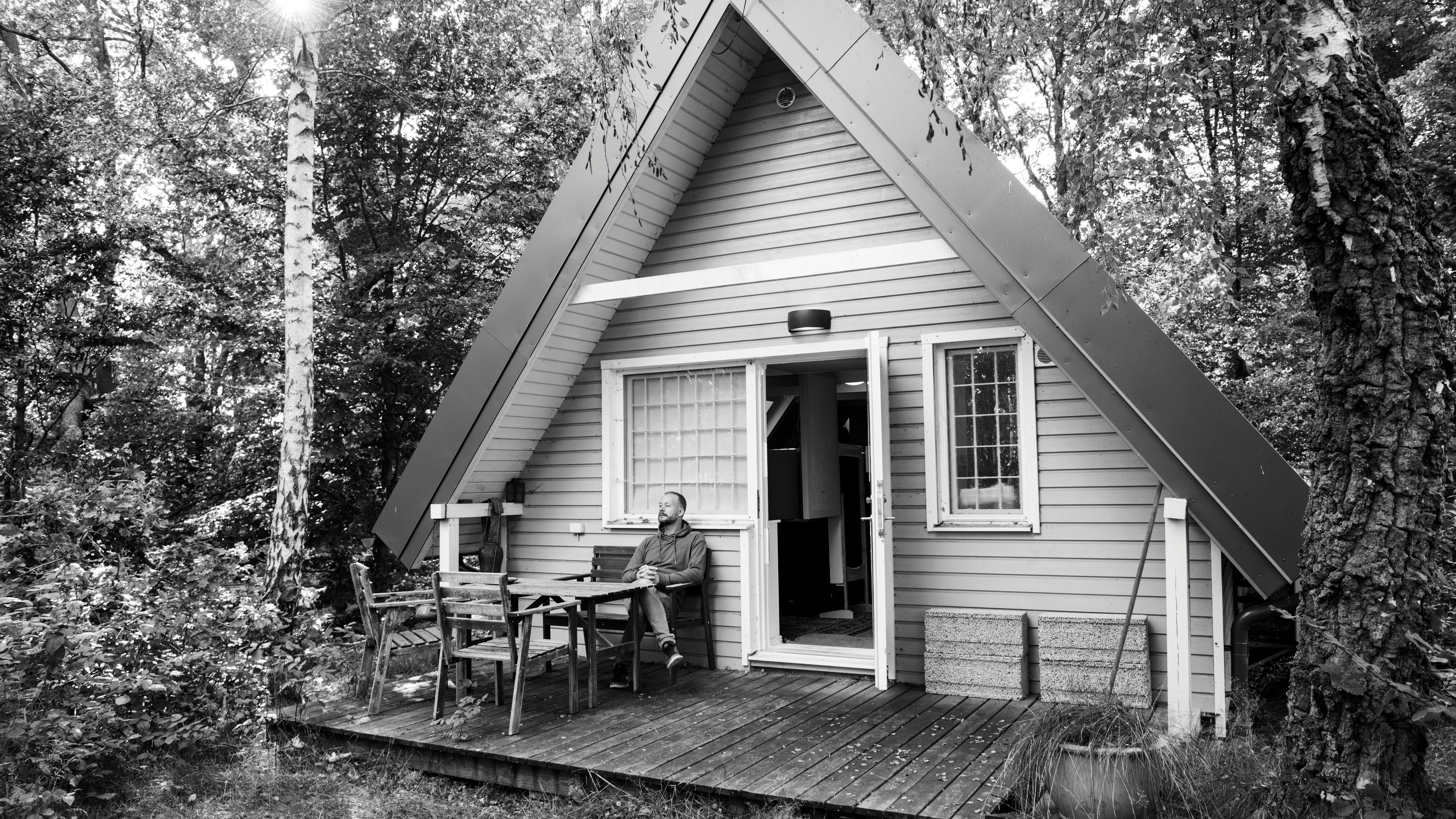

Sebastian Mullaert on his cabin-in-the-woods studio: "I walk into the beautiful forest and have all the tools to play around with and be a child"

Sebastian Mullaert talks to Danny Turner about his mentorship programme In Bloom and live jamming with Dorisburg

Integrity lies at the heart of Sebastian Mullaert’s outlook on creativity and sound. Best known as one half of the production duo Minilogue, his solo projects have become increasingly emboldened in recent years.

Prizing himself from the comfort of his luxurious cabin studio, Mullaert has sought to test his creative ideals through collaboration with like-minded artists and students enrolled to his In Bloom mentorship programme.

Mullaert’s latest partnership with Stockholm-based producer/DJ Alexander Berg (aka Dorisburg), typifies his newfound approach to creativity. Having found a common language with the fellow Swede, the duo returned to Mullaert’s studio in Röstånga to create a collection of audio jams.

After a pandemic-induced pause, the duo then took the recordings to Malmö’s Inkost venue where, via a series of live improvisational sessions, they created the abstract electronic album That Who Remembers.

When did you come across Alexander Berg’s work, and what made you think that collaborating would be a good idea?

“I connected with Alex’s music when he started to release under his solo project Dorisburg. I felt a very strong connection with his album Irrblos on Hivern Discs and his releases on Aniara Recordings, which is why I released an EP on that label for one of my other projects. When I launched my Circle of Live project in 2017, I was thinking about certain artists I wanted to invite, and Alex was one of those.

“In connection with that, we played together live quite a few times and he came to my studio in Sweden to make music for the first time in 2018. What we did back then was the seed for this new album, That Who Remembers.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The view of creativity and creative people has been distorted by this idea of someone being innovative, but I don’t believe the two should be mixed up

Can you take us a little deeper into that process?

“During the pandemic, I evolved my studio process and started a mentorship programme under Circle of Live called In Bloom, which is now an educational platform where I try to inspire and share my tools and workflow to allow students to develop. By doing that, I understood more about what my workflow looks like and what works for me as a solo artist.

“With Alex, I felt so well-connected personally and musically that I wanted to invite him into that process to see how it would work. We did a number of very free and unpretentious jams in the studio, recording different tracks separately from each other using a few machines. During the pandemic, everyone’s focus navigated to new realities, but at some point in the middle we decided to pick up where we left off.”

Tell us more about In Bloom and exactly what you’re teaching students?

“It’s an educational branch of Circle of Live. I do most of the classes, but I also have a little crew of teachers who have their own mentorships. My class has three steps, the first two are 10-week online courses and the last is a one-year session.

“Creative expression is the key to my teaching and something that is in our nature and accessible to everyone, but in my view it’s quite misunderstood in our society. The view of creativity and creative people has been distorted by this idea of someone being innovative, but I don’t believe the two should be mixed up. Some people just happen to be innovative at a particular moment in time.”

Everyone is creative and we need to express that to feel full. To me, creativity is necessary to heal and find balance in one’s life

Do you feel the link between creativity and innovation is too strong, particularly as innovators are few and far between?

“Everyone is creative and we need to express that to feel full. To me, creativity is necessary to heal and find balance in one’s life. My whole work is based on that and when it comes to electronic music I try to share ways to move away from certain misunderstandings in that field.

“The most common unbalance is that electronic music is a thought-based activity, which is a bit ironic because the reason that dance music is so popular is because it’s an invitation for an audience to be physical and express themselves. For me, it misses the point of music and musical expression, which is a sensorial experience. That’s what I like about my workflow with Alex; it’s a means to feel and to sense, and in doing that something takes form.”

Will you direct students down a particular creative path or would that defeat the object?

“It’s very common for us to tell people that they sing out of tune so they should not sing, but judging the result hinders people’s need to express something that is very important to them. The mistake that most people do every day is to calculate things that should not be calculated. Of course, some things need to be evaluated and measured, like healthcare and tax, but creative expression does not need to be measured and doing so hinders people from finding their balance.”

One element of the music-making process that could be construed as being calculated is production. What is your approach to teaching that?

“The first part of the mentorship is quite holistic, so it includes everything from meditation to ways of collaborating, nature, improvisation and my take on creativity but also my studio setup, workflow and live setup. We also teach people how to reach out with their music and all the different things you need to know as a professional artist, such as publishing, management, labels and booking agents.

“The second step is much more hands-on and focused on setting up an Ableton template, working with sound design, recording, making and arranging sketches and connecting and improvising with other people. The third part is for those who want to create a bigger piece of work over a longer time period, like an album project or live set, using my coaching or presence on a more one-to-one basis.”

What results have you seen from students in terms of them realising a final product?

“We had 15 artists from a wide range of backgrounds and levels of experience who all faced quite different needs and challenges. Almost all of them have completed recordings and songs that can be filtered down or curated into one piece of content, so the next big step is to send that out or help them to find a sense of community. Of course, some people really want to become artists, but my emphasis is not about making people famous, rather the opposite.

“For me, we should always start by trying to connect to that precious thing called creativity, then what really matters will become clearer and easier. A lot of artists who are professional and well-established also struggle to find their flow or feel like they have lost something, but it’s not difficult to take a few steps back and rediscover what you need to do to allow that natural creativity to start flowing again.”

By introducing the concept of understanding creativity first, are you basically teaching people not to run before they can walk?

“What I’m saying is not difficult and quite obvious. I look at my own kids who are at elementary school, but it feels like most Western educational platforms are missing out on learning the basic principles of energy, flow and curiosity that then have to be rediscovered when you’re 20, 30 or 40. Apparently, Rick Rubin has released a book that is very close to what I’m talking about that has had a big impact on those who have read it.”

When we talk about workflow and creative expression, so much of it is about psychology mixed with things that kind of just happen

In recent years, you appear to have been getting out of the studio more. Was that a result of the creative limitations of working solely within a studio environment?

“When we talk about workflow and creative expression, so much of it is about psychology mixed with things that kind of just happen. I’m very curious about enabling creativity in all aspects of my work, so it came naturally to me that I would like to find out how it works in other environments and constellations, whether that’s with one other person, an ensemble of acoustic instrumentalists or working with a singer-songwriter in genres based on song structure and composition.

"Right now, I’m finding that my workflow is hitting the right spot and helping me to avoid patterns that limit my creative flow.

“I’ve also come to a strong understanding that there are certain steps that I do with others that are beautiful and enable something that I can’t do alone. On the other side, I also love my studio over anything else. It’s in nature, 500 metres from my house and I can walk in the beautiful deep forest and have all the tools to sit in there, play around and be a child. I sometimes question why I go away to start these exhausting projects when I already have everything in this beautiful little hut.”

For this project with Alex, you both decided to set up your equipment and record at Malmö’s Inkonst venue. Why choose that location?

“It’s probably the most important and relevant venue for alternative electronic music in Sweden. It has a special soul and I’m very connected to the place, so it was easy for me to reach out to them and ask if Alex and I could spend a week there. We’d already played there several times together and separately and it’s also where I recorded my A Place Called • Inkonst album, so this was an extension of that process.

“We put a nice big sofa in a sweet spot at the club so that one of us could lie down and listen to the other jamming. It created a very relaxed approach where neither of us felt that we had to do something – we could just immerse ourselves in whatever the other was playing. Sometimes when you collaborate you feel that you need to find something to do when you’re actually just destroying what the other person is doing.”

You mentioned earlier that the Inkonst sessions were based on ideas created previously at your studio?

“Yes, the recordings were based on the sounds we’d made back in 2018 and in the weeks before we met up at Inkonst we remixed those sounds separately. That was the part I felt needed to be done by myself in the studio so I could add, tweak, loop, layer, re-pitch and create soundscapes. I asked Alex to do the same from a different room in my studio using some of my sound design gear until we’d created a big sample pool that had tons of soundscapes to take with us to Inkost. We then took some live instruments and recorded different sessions with them at the venue.”

What gear did you take to Inkost to continue developing the tracks?

“My setup was the same as what I use live, which is more controller-based. Obviously I didn’t have access to all my compressors and synths, so it was more about presenting or performing sounds made in the studio combined with a small amount of analogue synths, drum machines and software plugins.

“I used controllers to arrange, play and modulate the studio soundscapes and then I used a Korg Minilogue, Roland’s Boutique 101, a TR-8S and BOSS RC-202 for looping. Ableton Push was the centrepiece for playing analogue gear and audio in Ableton, but I also used a Yaeltex custom-made controller for controlling sounds I’d made in the studio.

“On the software side, I used various stuff from UAD, Roland Cloud, Native Instruments, Arturia and Ableton, which was all mapped and ready because I prefer not to change presets when playing live to avoid any glitches. Alex was also able to control and play samples and soundscapes that we’d created in the studio, but his jams were mostly enhanced using his live modular setup.”

Were you responding to each other intuitively?

“Yes, we just pressed record, played and I think we did about 80 takes. Sometimes we did a take alone and sometimes we started together and one of us would get into a certain flow and play on top of each other’s loops. We listened to our jams through the PA system but recorded straight out of our mixer.”

From your description, people might expect That Who Remembers to sound quite intense and club-oriented, but it’s not like that at all…

“There’s a logical reason why the album sounds so abstract and that’s because when you play alone in a club, or as I did with Alex, you don’t feel the need to do so much because even a 909 kick drum sounds aggressive.

"I’ve also noticed this when we do workshops, retreats and sensorial exercises, when you start to welcome the subtlety of the world around you and connect to that energy flow, you don’t need to trigger too much information and tend to create something that sounds more minimalistic.

“In a club environment that can be challenging because you face restlessness from the audience and have to come up with quick fixes because they’re not as tuned in to your sensorial input, but that’s not their fault because it’s what they’re used to.”

In that environment, did you have to resist the temptation to create club-oriented mixes?

“Alex and I talked about that quite a lot and wondered whether we could create a mix as a promotional tool for the album that was different but somehow still connected to it. Eventually, we decided to take parts from other people’s music and make some spontaneous edits with sounds mixed from our songs.

“Doing that at Inkost felt like it might be too complicated, so Alex came down to my studio and we came up with 28 edits of really punchy dance music. It’s ironic how those dance mixes were made in my studio yet the album, which is much deeper and more futuristic, was made in a club.”

There does seem to be a slight echo to the tracks, denoting that the album was not recorded in a studio…

“My motto these days is whatever comes out, comes out. I feel attracted to things that sound warm, imperfect and beautiful in their dusty, misty shape rather than creating clinical and perfect expressions. I want art and music to awaken the life in me rather than distance myself from that.”

Once you’d recorded everything with Alex at Inkost, was anything else done to prepare the tracks for release as an album?

“We didn’t edit, change or mix anything. What the tracks sound like is exactly how we played them at Inkost, although we did shorten things to make them fit on a vinyl release. We took a deeper and more avant-garde journey than I’d expected, but that’s one of the most important aspects of taking a sensorial approach to music-making – you leave your thoughts and expectations in the waiting room and make something that you really wanted to but didn’t know it.”

Dorisburg and Sebastian Mullaert's album That Who Remembers is out now on Spazio Disponibilie.

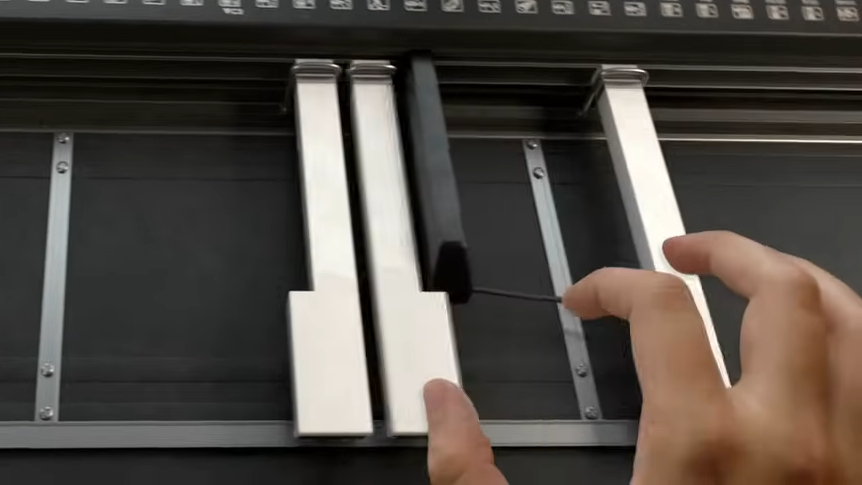

“If this was real, it would be really impressive. But since it’s not real, it’s really impressive": Watch the bonkers four-note piano

"I said, ‘What’s that?!’ He looked at me strange and said, ‘We’re line checking. We’ll be gone in five minutes’. I said, ‘You won’t - meet me in that room in 10 minutes’": How a happy synth accident inspired a US number 1 single for Terence Trent D’Arby