Ruston Kelly: “Brutish and kind of rude and beautiful - that was the kind of art that I wanted to make”

The rising alt-country songwriter discusses addiction, songwriting and his disarming debut Dying Star

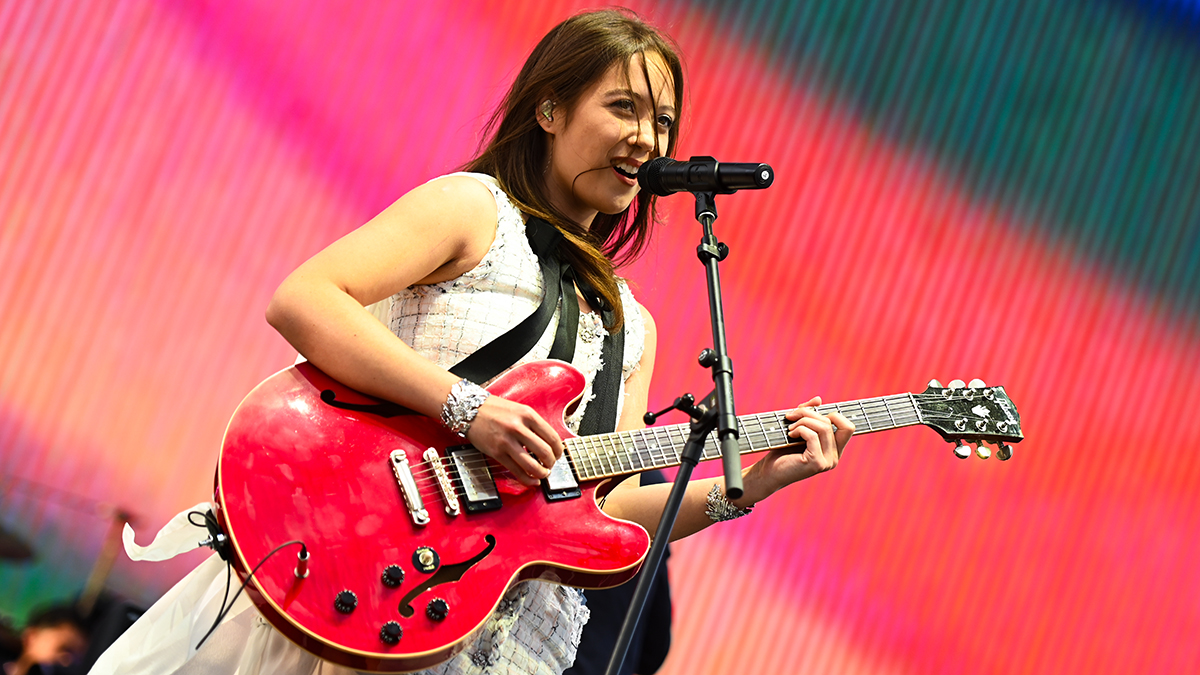

Ruston Kelly made his name in Nashville first as a songwriter, penning tunes for the likes of Tim McGraw and the Josh Abbott Band. Now he’s channeled his stream of consciousness songcraft into a debut album Dying Star.

The record charts his journey from pill-popping madness to sobriety, packaging sometimes-brutal honesty in graceful alt-country forms.

When we catch up with the songwriter, he’s enjoying a rare moment of rest and serendipity, as he and his wife, country star Kacey Musgraves, both find themselves at home.

Lately, I've been able to re-approach the guitar and remember that I'm not done learning yet

“I’m trying to appreciate the downtime. I'm restless but also frustrated about being restless,” says Kelly.

“But my wife and I are home at the same time. That is an extremely lucky convergence of the stars, so I’m trying to appreciate that today! When I do find myself having downtime, I just put my guitar in my hands. Lately, I've been able to re-approach the guitar and remember that I'm not done learning yet.”

What have you been working on as a guitarist during your recent downtime?

"I would say finding a sense of finesse on the fingerpicking side of things within this new tuning [Bb F C F F C] that I discovered and used largely on Dying Star. I call it Maria tuning because that's the name of my guardian angel and that's what I think heaven will sound like!

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"It took my so long to learn how to sing to it because it felt like it was already saying so much. It was a tuning that needed to be played fully and be strummed and have this oceanic wash of sentimentality, for lack of a better word. It sounded really angelic to me. So now I'm picking that and finding a lot of inspiration where I can pick out these individual notes in tuning and finding a lot of chords, so it's really a new playground. It's very exciting."

Your parents, particularly your dad, both played guitar throughout your childhood, but you didn’t pick it up until you were about 13. Why was that?

"I would say that I needed to experience life a little bit. It's always informed my playing and expression and that's what art is to me. I was writing songs, I guess, a sense of lyricism before I started picking up the guitar. Once I picked up the guitar, I felt I started expressing myself in that medium without words.

"It wasn't until I was about 15 that I put the two together and I found this great synergy between what I had to say and the voicings that I pick and that they could inform each other. To do this day, one of the things I love to do onstage is make up songs on the spot and that's how one of the songs on this record came out – I made it up in the studio.

"The way I play, I don't know how to say, 'I'm doing this or that', but I know what I need to say with it and there's this internal movement and expression that comes out with that."

What song did you make up on the spot?

Songwriting has always been a means to an end for me. That end being a tool to try to understand myself in the world and, through observation, make sense of the world

"Brightly Burst Into The Air, the last song on the record. What's funny about that is that I knew the title of that song before it was written. It was the day after I overdosed and I came to or woke up or whatever you wanna say: came back to life. I went out on my porch and I was like, 'What the fuck? How is this happening over and over?' The words Dying Star came into my head and I instantly knew that it would be the name of this record that I was going to make and 'brightly burst into the air' popped into my head and I knew that would be the very last track on the record.

"I didn't write it until I got into the studio, that was like a year and a half later. I had a chord progression-ish and I was like, 'Hey guys, let's get weird. I kind of feel it coming...' so we pressed record and that was what came out."

I saw a quote from you about “Allowing the worst parts to be the ones you expose most in artistic sense.” Does channeling them in an artistic sense allow you to manage the worst parts of you more in real life? Or is that a cliche?

"No, I think it's a hundred per cent true. Songwriting has always been a means to an end for me. That end being a tool to try to understand myself in the world and, through observation, make sense of the world. Through that, I think there could be a tendency to live too hard in your art work and think that you are 'this' or 'that'.

"It's only recently that I've been able to separate those things and allow the information that I get from expressing myself to inform the better parts of myself. I still sing about overdosing or heartbreak or things that I don't experience any more. We hold these things in and we need a way to express them cleanly and in a healthy way.

"It's funny, you can express yourself and someone's always going to have something to fucking say about it. Sure, 'I took too many pills again' [a line from Faceplant], OK, I'm not doing that any more, but I needed to say that."

You’re into your literature: you’ve previously name-checked Charles Bukowski, Sylvia Plath and you’re also into the Beat poets, crediting your sister’s influence at a young age. How have those names impacted you as a songwriter?

“[At first] I just happened to jive with their sense... like I didn't know there was a literary school of thought behind this stream-of-consciousness writing. I didn't know it was a thing. I didn't know that the Beats pretty much founded themselves on that. They were able to say something so quickly, bluntly and passionately. There was fire behind it. It was right in your face and probably the most honest writing I had ever read before.

"It was also poetic and it wasn't like some Robert Frost poem – and I do like Robert Frost – but it wasn't dripping with poetic moves and this sense that literary critics were going to sit down and get their spectacles out. It was brutish and kind of rude and beautiful and that was the kind of art that I wanted to make."

You’ve also referenced your love of the likes of Death, Misfits, Slayer, alongside the likes of Ryan Adams and Jackson Browne. Slayer, for instance, seem an unlikely influence at first. What draws you to them?

I feel like irreverence should be synonymous with artistic expression. That's why listening to modern radio is a little bit frustrating, because everything is so safe

"They take any sentimentality and they throw it on its head and bash it and kick it. I think that's a huge aspect to being a self-proclaimed 'artist'. I feel like irreverence should be synonymous with artistic expression. That's why listening to modern radio is a little bit frustrating, because everything is so safe.

"Black-metal is my favourite. Mayhem are one of my favourite bands. But whenever Slayer comes to town, I am going to that show. To me that's what Bukowski is: he is Slayer. He is black metal. I think that they do the same thing. Irreverent and honest and brutal. We hold so many things in – to our detriment. I feel like metal completely lets it all out."

When did you get your first good guitar and what was it?

"The first guitar I ever put my hands on was a Martin D-28 that my dad bought [new] in '71, which is obviously a fantastic guitar. He let me play it but he had to supervise me. And by 'playing it', I mean I just held it in my hands in awe and he showed me how to play a D chord.

"But I'll say the first guitar that made an impression on me was by this Japanese company – I don't think they're around anymore – called Daion. I believe it was an L999 model and it was this beautiful dark brown, I think it might have been mahogany [our research suggests it was more likely rosewood - ed]. It was my mom's guitar because she was this like heady-assed folk singer, back in the day! She would take her guitar into the woods and, literally, sing to the trees, so it had a lot of good energy on it! [laughs]”

We first heard you on To June This Morning from the Johnny Cash Forever Words compilation. John Carter Cash recently described that song to us as “the simple image of his life at the time. It’s hope.” Both you and Kacey seem to inhabit those words very convincingly. Do you think you’re getting better at hope?

"I think that was one of the first steps. Talking to John Carter about that, he knows my history and I didn't want [the song] to be some romanticised version, but surely, yeah, when I met my wife she cleaned me up and she gave me a reason to stay clean. Like, 'Let's do this thing as long as we can.'

"John Carter called me out there, we sat at his coffee table, we had some coffee and he was like, 'Man, I'm just gonna say it. Y'all remind me of my mom and dad and I feel like that's what's missing on this project – I'd love for you to sing on it.' [He’d never heard To June This Morning and] I was like, 'You should see it.' As he was reading through it, I saw him get tears in his eyes and he looked at me and he goes, 'Wow, this date: my mom was eight months' pregnant with me when my dad wrote this...'

"To be able to sit there with him, knowing what I went through and what my wife has brought to the table when it come to me being a man and the family that we want to start together… Yes, that was definitely step one in the right direction."

Dying Star is out now via Rounder Music. Ruston Kelly will play a one-off show at London’s The Slaughtered Lamb on 17 September and return to the UK for dates in November/December after an extensive US tour.

Matt is a freelance journalist who has spent the last decade interviewing musicians for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.

“I’m beyond excited to introduce the next evolution of the MT15”: PRS announces refresh of tube amp lineup with the all-new Archon Classic and a high-gain power-up for the Mark Tremonti lunchbox head

"You can repurchase if it works for your schedule": Fyre 2, Billy McFarland’s ‘luxury’ festival is postponed indefinitely

![PRS Archon Classic and Mark Tremonti MT 15 v2: the newly redesigned tube amps offer a host of new features and tones, with the Alter Bridge guitarist's new lunchbox head [right] featuring the Overdrive channel from his MT 100 head, and there's a half-power switch, too.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/FD37q5pRLCQDhCpT8y94Zi.jpg)