Roman Flügel on his production philosophy, and why he still wants a Moog

We meet the German ‘chameleon’ whose addiction to synthesizers shows little sign of abating

Few artists are able to inject a sense of soulful sustenance into the quirky world of electronic music. While some genres are burdened by their own dogmatism, Roman Flügel’s multifaceted approach has always been enlightening.

Since 1995, the German workaholic has amassed seven solo projects (including Eight Miles High and Soylent Green) and nine collaborative aliases. To illustrate his diversity, you only have to look at Flügel’s output. Despite not arriving until quite late in his career, his solo debut album Fatty Folders (2011) was a journey into mellow tech house, followed three years later by the punchy electronic pop of Happiness Is Happening. Meanwhile, this year’s All The Right Noises once again demonstrates Flügel’s eclectic mix of styles, falling evasively between the apertures of traditional house and techno.

In terms of sound creation, Flügel is a hardware buff and synth fan, having amassed a hefty collection over the years. However, while he is more than happy to absorb what the digital world has to offer, he doesn't consider himself a laptop producer and would prefer not to be defined by the technology he uses. More important is his commitment to sound itself and his ongoing desire to locate the source of his creativity.

Some people might not know, but the first music you got into was EBM, which is a dance splinter of Industrial music…

“That was definitely part of my youth when I grew up in the 80s. It was between 84 and 86, right before acid house hit Germany, I would say. There was this period of time when I was really into that electronic music, which was coming from Belgium: bands like Front 242, Nitzer Ebb from the UK and Skinny Puppy in Canada. But things changed very quickly when I heard the first acid house tracks back around 87. I’m sure there are still a few EBM fans here and there, but back then it was all part of my youth culture.”

Your latest album, All The Right Noises, is very serene. Was writing and recording the album an antidote to the hectic world of DJing?

“I would say it’s always been like this for me. Growing up with techno in the 90s, there was always this ‘night’ experience, but then you also had the next day and a big part of that was stuff like Warp Records and the more chilled sound. So while I’ve released plenty of 12-inches and club music, I’ve also made music to listen to or home listening music. I would say that with this latest album, everything is more connected to me.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Your music’s always had a strong identity, but would you agree that you’re a non-conformist?

“I’m trying to achieve this and it’s not something that I think about too much, but I think it’s important to not just imitate. Of course you might start imitating in the beginning - that’s how you learn how to do things - but then it’s very important that you try to shape your own sound and character within the music you’re making.”

Much of the music on the new album was a result of live takes. Did you aim to avoid quantising or perfecting the sound too much?

“Some of it was live takes with less quantising, just playing with my fingers, recording and then doing little edits here and there. But that approach is something that’s changed over the years. I’ve finally found it more interesting to be less obsessed with perfection, whatever that means, and having a certain amount of levity within the creation process, just letting things happen without trying to cleanse everything.”

Does creativity still come naturally to you, or do you have to work harder to cultivate an environment in which you can be creative?

“First of all, it comes naturally, but it’s a lot of work at the same time. If I don’t go to the studio and do something every day, there’s hardly anything coming out. I need to have this constant workflow to do something I’m satisfied with at the end. I usually go into my studio every day, where I can be playful and start to record and use those opportunities I have to trigger my creativity. If I lean back and wait for something to happen, nothing will happen.”

Does experience allow you to throw out what’s unnecessary from the production so you can focus on the essence of whatever you’re trying to get across?

“I definitely feel that a lot more these days than when I first started. Over the years, you find your own way to treat instruments and their possibilities, and I found out that it’s a lot more important to keep the essence of what you are trying to create rather than recording track after track after track.”

How do you get a clear separation of sounds, and how important is sound placement?

“Well, for me it’s always about putting the lower frequencies in focus. If you do club music, there is always the balance between the bass drum and the bass frequencies, which is very delicate. I found out at a certain point that it’s very important to separate certain frequencies from each other to get a good result in the mix. For example, there are always some frequencies that are a bit disturbing and make things a lot more difficult to mix, so I’m looking for those disturbing frequencies and trying to separate things in the stereo band by working a little bit on the EQ.”

Do you adopt certain principles when it comes to EQing?

“I’m not usually too harsh when using EQs. I don’t use them to extremes, just to come close to the sound I want to have, because you always have to find a balance. If you push a lot of treble then you probably have to push a lot of bass as well, but that doesn’t make the music sound a lot better in most cases. It’s the same with mid frequencies: they can be really harsh in the beginning and you think they’re going to sound brilliant, but after a while they actually sound quite annoying.”

I’m not usually too harsh when using EQs. I don’t use them to extremes, just to come close to the sound I want to have, because you always have to find a balance.

Is EQ something you analyse right at the start, or is it best left to the final mix?

“I would say I do it when I collect ideas. Sometimes collecting ideas is a lot faster than doing the EQing, but I at least try to listen to the mix at the very beginning to see if something is too disturbing or doesn’t sound right. At the very end, once I’ve done the final mix, I check it again to take a look at the EQs and the final stereo sequence.

“Of course, finally I go to a mastering studio to use someone who helps me [laughs]. I’d say I do 50% in the studio and the other 50% is done during the mastering process.”

Have you found someone you can trust who truly understands what you’re trying to achieve?

“I actually found someone who used to work with dub plates and mastering - his name is Lupo. I’ve been working with him for many years now and we have a good relationship. As soon as he gets the files, we talk about the music and then he does his own work on it. I don’t usually go to his studio because he knows what I like, but it’s very important to get along with him and have the same perspective so we can hear the same things that need to be changed. You want somebody who listens a bit differently to you and also has an interesting view on what to change. For example, making things louder without destroying the mix - some people think it’s an easy thing to do but it’s not at all, and that’s something I leave to my mastering engineer. It’s the same with very detailed frequencies or transients - he knows the technical side a lot better than me, has the best equipment and knows exactly how to use it.”

Do you adopt a less is more approach to reverb and delay too?

“After all these years, I have a few effects that I use a lot because I’m very familiar with them, and that includes on the digital side. I have a few settings that I’ve created on my own - a chain of delays and reverbs that works best for me and gives my music a certain character. I’m not trying to program something new all the time. When it comes to using chains of effects, there are certain parts of the production where I go back to techniques that I’ve used before, things that work well for me and shape my personal sound.”

So creating your own identity can be done just as easily by creating a chain of production techniques as using particular sounds?

“Yes, and I think that’s something that comes once you start working in production on a very constant basis. These days, I know exactly where I will end up by doing something, and there are certain chains of events that not only work well for me but work in terms of sound, and that has become an important component in the creation of my own sound.”

For delay, you use the analogue Ibanez Time Machine and a digital DM1000…

“I think what is very important to my music is the combination of everything in my studio. I’m not a laptop producer, but I’m not a computer nerd either. I have plugins and all the digital options in my computer, but it’s very important to use a lot of outboard, too.

“You mentioned the Time Machine, which has such a specific character. The delay and the flanger can give the music a very specific flavour, and I like to combine this with an old reverb from Ensoniq. Combining those things can allow you to come up with something extremely interesting.”

So you prefer using analogue gear to plugins?

“It’s not about using pre-programmed plugins all the time, but combining things to come up with something new. That’s why I never sold anything and just bought things and kept them in my studio. After all these years, I have this collection of things to use, like old effects reverbs from the 80s. It’s just something I really like; they have a certain character and you can also get them quite cheap [laughs].”

What else do you use for effects?

“I use the Eventide H3000 B Ultra-Harmonizer, because the chorus and flangers can be used in a very drastic way, allowing you to create some very interesting things within your stereo range. It also has some pretty crazy effects in it that are especially good for percussion.

“The Eventide produces a very interesting and flexible effect that is of a very high quality. The one that I have is made especially for guitarists, but I use it for something very different.”

In terms of software, you use Logic, but mostly as a sequencer rather than a sound generating tool…

“I use it for sequencing MIDI, obviously, but it’s also my digital tape machine, so I use it for a lot of wave data within Logic and arranging different tracks. With the MIDI stuff, everything goes through my mixing desk and back into Logic. Basically, I record everything on my mixing desk, combine all of the effects, and then go through a Fireface 800 audio interface and back into Logic.”

Waves is your go-to software package. Do you think it complements analogue hardware?

“There are plenty of things to discover within the Waves package, but at the very end, there are only a few things that I’m using a lot. It’s pretty much the same as everything - you find out about certain settings you really like and start using them; but I’m very happy with everything that Waves Complete offers.

“All the software packages are so flexible and useful that I don’t really need to buy new ones all the time. I’m already confused by the amount of sounds I have in my computer; it’s incredible what they offer - even just using the sounds within Logic.”

How are you using Ableton Live these days?

“I’m using Ableton for certain things because it’s so easy to use, particularly for doing interesting loops in a very fast way. When I prepare things for my DJ sets, I start recording old records and doing edits, which is also very easy to do in Ableton.”

So when it comes to performing live, you’re using Ableton and the Technics 1210s we notice you still have.

“I used to play live for a couple of years, and back then I used Ableton Live, but these days I don’t play live any more - I just DJ - so I’m not using Ableton.

“Honestly, I would love to play live one day but I’m just waiting for the right concept, because I don’t want to just open a laptop and press play. In the very beginning, I was travelling without a laptop and using hardware sequencers, which was not only a lot of work but I was always afraid during the soundcheck whether everything would run smoothly. So I’d rather do something with other people then maybe try to recreate whatever we did in the studio on a different level in a live situation.”

You have a Teac A-3340 reel-to-reel tape deck. Is that to get tape saturation into your sounds?

“I used to do that in the past, but right now it’s unfortunately broken. I need to get it repaired, but it’s a great machine. I used to record with it when I was in my first band, because that was our only way to record music back then. They are quite fragile, and it’s not very easy to find someone who can do a good job in repairing it.”

You have some drums and a guitar in your studio. We can’t hear them on the album, but do acoustics make it onto your records?

“Not on the last couple. The first solo album I did, some of the recordings were made with live instruments, but again they were processed in the computer, so they are quite disguised.

“I used to play drums in the past, when I was in bands, and still have them set up in the studio. I can’t really play the guitar - my brother used to play the Ibanez - but it’s good for doing sounds that don’t sound like a guitar, more like drone sounds.”

You have a ton of hardware synths. When did this addiction start?

“It started very early on. I’d already played in bands and always tried to play the synthesisers because I liked them so much. In the early days, we had a Yamaha DX7. But the addiction started when I was a child, because my uncle had a lot of musical gear in his house and also owned a Roland System 100. In those days, I was happy to mess around in his music room, turn knobs and press the synth. At a certain point, I was able to buy things here and there - it first stated when I bought the Roland JX-3P in 1987.”

Your JX-3P has a PG-200 Programmer, which looks like some sort of module add-on…

“It’s a small programmer that was part of the instrument back then. You put it on the side of the instrument because there’s a space there that’s magnetic, so it sticks to the synthesiser, and finally you have a very easy way to access all of its parameters. You could program the JX-3P without using the programmer, but only by using a certain combination of knobs, which is a lot of hard work, so the PG-200 helps a lot.”

Which Roland synths really stand out for you?

“For me, the standout Roland synth is the MKS-80 Super Jupiter with the MPG-80 programmer. That is a very beautiful instrument. It’s very flexible because you can create almost any sound with it, and it has this beautiful string sound. I would say that the most beautiful string sounds always come out of this instrument.”

Are you interested in the refaced synths that have been coming out recently?

“To be honest, I don’t have any of these because I have all the original synths. It’s a bit difficult for me to be too enthusiastic about them because it’s almost like people are looking back too often. The cult is there already with all these instruments, so I’m not too sure about the concept of reproducing them for very cheap money; but it seems to work very well for all those companies.”

You have the classic Yamaha DX100, but also the DX200, which is not the evolution some might have expected but more like a very colourful desktop sequencer…

“Right now, the DX200 is a machine that many people are looking for. It used to be pretty cheap back then. It was kind of a workstation with a sequencer that had two or three drum tracks, one synth line and different effects, but it has a very interesting concept when it comes to creating FM synthesis.

“When the DX100 came out, and the DX7, which also has FM synthesis inside, it wasn’t really easy to program; but the DX200 has knobs to twiddle and is very accessible. Actually, the DX100 played a major role in early techno. One of the reasons I bought it is because there were a few sounds inside it that were already used in early Detroit techno and Chicago house music.”

For me, the standout Roland synth is the MKS-80 Super Jupiter with the MPG-80 programmer. That is a very beautiful instrument.

Talk to us about the bizarre-looking Oberheim Matrix 1000 and its Access Programmer?

“The Oberheim Matrix 1000 used to be a very common synthesiser in the 80s. It has this beautiful Oberheim sound, but you couldn’t change or program them. At a certain point, there was this company called Access that put out the programmer. So at the end of the 80s I bought the programmer and suddenly had an opportunity to make my own sounds on the Matrix. Finally, it was like having the big OBX synthesiser, where you could change every sound in front of you.”

Are your hardware synths all wired up to one console?

“Yes, that’s the concept. Everything is connected to the mixing desk to give me as much flexibility as possible - I just have to change a cable here and there. I don’t usually have many problems with my setups, because you can change the delay of your MIDI instruments within Logic and you’re ready to go.

“Usually it’s stable, but it’s never the same as whatever you might have set up in your computer. But that’s all part of using MIDI - there’s always latency involved.”

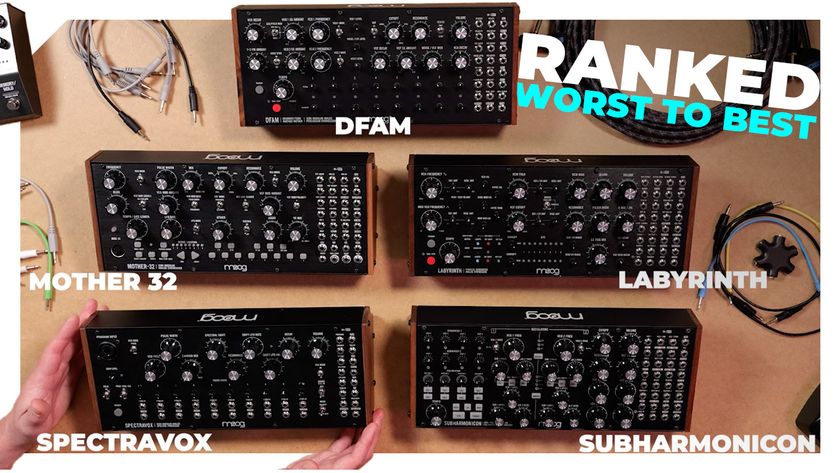

Are there any synths you would still love to add to your collection?

Yes, I would still love to have a Moog synthesiser one day. The characteristic sound of the Moog is something that’s completely missing in my setup. It’s basic, but at the same time I find that the Moog sound has a very unique character.”

All The Right Noises is out now via Dial. Check out Roman's Facebook page for more info and tour dates.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.