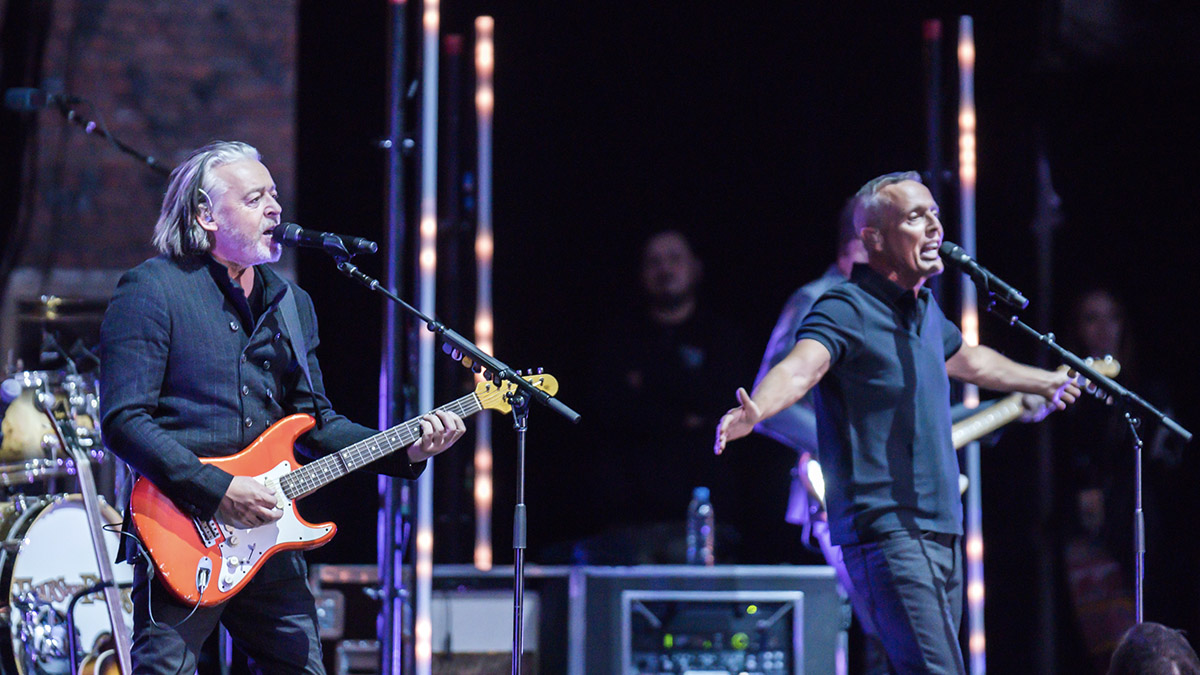

Tears for Fears' Roland Orzabal: “My favourite guitarists are probably David Byrne and Paul Weller. I love anyone who can hit an open chord and make it sing”

Best of 2022: As Tears For Fears return with their first album in 17 years, Orzabal discusses guitars, synths, the evolution of their sound, and why he and Curt Smith had to forget about writing hits

Join us for our traditional look back at the stories and features that hit the spot in 2022

Best of 2022: Tears For Fears have always been a band of contradictions and contrasts. Theirs is a sound that was borne of the revolutionary aesthetic potential of the synthesizer. Foregrounding melodies and hooks, they assumed their place at the vanguard of the synth-pop movement that dominated the charts throughout the ’80s. The hits kept coming.

But despite their popularity, and despite finding creative inspiration in this new technology that augmented pop-culture for keeps, it was only ever one part of the story. For all the synthesized arrangements, once a show came around, Orzabal played the guitar, Smith played bass guitar. There was depth to their arrangements. There were layers.

Co-founded in 1981 by Curt Smith and Roland Orzabal in Bath, England, Tears For Fears’ had a set of influences and creative principles that would see them skew more musically progressive than their peers.

In the ‘80s, when prog tendencies could be a hard sell, the synth could be applied as a modernist sheen, future-proofing rhythms, giving melodies a contemporary feel, a buoyancy that might have been lost if they had been performed on an electric guitar lest they be heard for what they truly are.

This is how MusicRadar’s Daniel Griffiths drew the distinction between Tears For Fears and new-wave synth contemporaries The Human League and Heaven 17. As Orzabal joins us over Zoom and contemplates Tears For Fears’ place in the evolutionary path of synth music – “not at the forefront,” by his reckoning – he can see the logic.

“[He] was describing the difference between some of the early synth bands which he called ‘utopian’,” says Orzabal. “We were almost too musical because we could play more than one note on a keyboard, and that sort of differentiated us, and pushed us into what he considered [to be] hiding our prog rock roots within the new synthesizer revolution. I don’t know how true that is, but I like the idea.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Tears For Fears’ first album in 17 years, The Tipping Point, makes the argument more convincingly. Years of drift between Orzabal and Smith have been rolled back. This is quintessentially Tears For Fears, doing what they have always done. There’s a sleight of hand to their songwriting. Smith and Orzabal retain that gift of being narratively oblique in verse.

The title track traffics in an insistent but elegiac melody and is given a pristine sheen via additional programming from Florian Reutter. The Tipping Point feels relevant to a world in which a number of tipping points – environmental, political, etc – have been reached, and yet it is a deeply personal song about Orzabal losing his late wife Caroline.

In the press release, he describes it as “an image of a hospital room where you are just looking at someone and waiting for the point when they are more dead than alive. That’s the tipping point, and it’s almost like part of you is willing to cross that threshold because you are in that purgatory while they’re in purgatory.”

With Tears For Fears, what’s personal and what can be seen as a comment on the world around them can seem interchangeable, always open to the audience’s interpretation.

The audience might well interpret this album in the same way as its ‘80s forebears, glomming onto End Of Night's ecstatic hooks, the urgency of Break The Man, and to producer Charlton Pettus’ uncanny ability to find fresh sounds to complement Orzabal and Smith’s writing.

Hits might come of it but that was never the goal. The album could only begin to came together once he and Smith had stopped thinking about the hits and got down to the fundamentals; paring Tears For Fears back to two friends with acoustic guitars and working through a folkish riff just to see what would come of it. Or, as Orzabal puts it, enjoying the “simple pleasure of making music as Tears For Fears”.

You spoke about the significance of writing together for No Small Thing. Was that when the record really felt like it was happening, that you believed you were going to get it done?

“Yeah, at that point in time we weren’t sure if we were going to do a record. I mean, Curt was kind of getting cold feet about everything. Twenty-nineteen had been a tough time for us touring-wise. Not the first arena tour, which was very well coordinated and it was great fun, but the festival tour in the summer. It was during three heatwaves where people were literally being gurney’d out of the audience – people around our age! [Laughs] It was like, ‘Woah! Are we gonna get through this!?’

It was very, very important to get together with Curt, like we did when we were kids, and put our minds together

“And there were a few shenanigans going on with the management as well, who failed to sign our album to Universal even though Universal had taken two tracks from it for the Greatest Hits, so were left with this album up in the air, slightly depleted, and Curt didn’t like the vast majority of it.

“I had a lot of faith in some of it – I knew it could be reworked. But what had happened during the initial recording sessions, which lasted a few years, Curt and I weren’t really communicating because we were surrounded by a team of other songwriters, other musicians, and Curt’s voice was getting a bit lost.”

You had to reestablish that relationship, and get in a room to write with no distractions?

“I felt that it was very, very important to get together with him, like we did when we were kids, and put our minds together. And when I say put our minds together, I mean to allow him to influence me directly; let him feel what it’s like to be influenced by me directly again. I was pretty confident going round to his house that something would emerge, and then he just played this acoustic guitar figure and we were off.

“I brought my laptop around. I was programming stuff up. It was that simple pleasure of making music as Tears For Fears – without anyone else – and the freedom that we were experiencing all of a sudden having abandoned this quest, this mythic quest, for the hit single. We abandoned it and then the whole world opened up for us.

“It took me a while to get the verse to No Small Thing because I tried three different things but the lyrics – ‘Freedom is no small thing’ – just seemed so [prescient]. This was pre-lockdown! [Laughs] When lockdown happened and all the riots, all the protests, and the world being turned upside down on its head, that song just grew more and more in meaning.”

The world feels like it has been slowly turning on its head for a while.

“I still feel like the issues are being cherrypicked, if you see what I’m saying. You have got the government, a lot of governments on a war footing, focused on one thing, getting us to focus on one thing, constantly reminding us to be afraid.

“And I do wonder if the same techniques and the same pressures were directed towards climate change, then all of a sudden, would that not be more of a sensible way forward? I don’t know.”

I can’t take credit for popularising synthesizers because before us were Kraftwerk. Gary Numan had already been at number one, twice

It is hard to say. The solutions to humanity's problems seem to be within our grasp, and yet still seem out of reach.

“Yeah, absolutely.”

Is that one of the themes of the album? You’ve got this Janus-faced quality to your writing, where the gaze can be turned outwards to address broader issues, but also inwards, more personal. It’s like a Rorschach test for the listener. We get to decide how we want to interpret it.

“That’s a beautiful way of looking at it. That’s a great description. I would say pretty much all the songs start with what it means to me personally. The Tipping Point is an obvious one because I was aware of the phrase for many years, I thought, ‘I quite like that.’ And then when I wrote the melody and lyric to that song, and the background to which you have probably read about, with my wife [Caroline], my late wife now, suffering from mental illness and literally becoming a ghost of her former self.

“Personally, the tipping point was, 'Will you ever know if it’s the tipping point? Is this situation just going to carry on and carry on and carry on? Or will there come a time where you have to say goodbye?' I didn’t know at the time when I wrote that song.”

And out of something deeply personal, you have this song that could have a very different resonance depending on who is listening to it.

“Curt sees it differently, because he sees The Tipping Point as a more global thing, and you can read it as both. Likewise, with No Small Thing. It was literally something quite simple about freedom of expression, but in this day and age, freedom has almost become a dirty word.

“We do muck about with personal meaning and collective meaning, and they are interconnected in a way which we don’t quite understand – the inner world and the outer world. Your Rorschach test, if you like.”

You were part of the first cohort to use the synthesizer in pop records. It was a bit like how Eddie Cochran and electric guitar, a technological shift that changed pop culture’s aesthetic.

“It was but we weren’t at the forefront of these things. I can’t take credit for that because before us were Kraftwerk. Gary Numan had already been at number one, twice, with these crazy synthesized bands. There were bands like Orchestral Manouevres In The Dark, Depeche Mode, Human League…

Well, if the synthesizer wasn’t there, wasn’t available to present you with these new ideas, then perhaps your songs would have remained prog. Because there’s a subversiveness to your pop sound, in how you have these musically progressive ideas but you disguise it in the compositions.

“It is subversive in as much as you have these crazy, cutting-edge synthesizer sounds, layering... And Mad World, when we came out with that, that was a classic example of hiding the meaning of the song in a whole glorious backdrop of crazy arrangements, and cutting-edge synthesizers.

We hid a lot of prog ideas because we were making pop music. It was up-tempo pop music, but the songs themselves could have been anything

“It is not really until decades later, when someone comes and sings that song without that arrangement, that you start to realise actually how breathtakingly honest – and if you like, subversive as well – Mad World is. We hid a lot of it because we were making pop music. It was up-tempo pop music but the songs themselves could have been anything.”

Where do the guitars fit in?

“Well Curt and I are guitarists. He is a bass guitarist, and I am a guitarist. And certainly a lot of songs are written on the guitar, and they are playable on the guitar. They got slightly buried on the first album because it was a very fragile album, very delicate, and we were focused on these wonderful, slightly experimental sounds.

“My favourite guitarists are probably David Byrne and Paul Weller. I love anyone who can hit an open chord and make it sing. It’s incredible. And, of course, being Beatles maniacs, loved those Harrison/Lennon guitars as well. As we progressed, we were going out on tour and we were playing guitars because that was our chosen way of expressing ourselves. They became more and more to the forefront.

When we did Seeds Of Love, we had God knows how many guitarists come in. Anyone who was passing through London would pop into the studio and we would record them

“There was a push after The Hurting and into [Songs From The] Big Chair to really ramp it up. I mean, there are crazy guitar solos all of a sudden; we were playing rock guitar solos! We would never have done that on the album before. When we did Seeds Of Love, we had God knows how many guitarists come in.

“Anyone who was passing through London would pop into the studio and we would record them! We had some incredible players. That, again, became very, very muso, and not at all like the style in which we started.”

It sounds like the guitar was always a key component but that it grew in importance.

“After Curt and I went our separate ways, on Elemental and Raoul And The Kings Of Spain, my partner then was Alan Griffiths, who is sadly no longer with us but [was] an incredible guitarist. Absolutely incredible! The soundscapes he would create? There was the line between the magic that comes from a synthesizer pad, or something that has generally been designed for you, and with Al and what he was doing with his guitar, there wasn’t an obvious gap between the two.

“Now, after that, with Charlton Pettus, who has produced a lot of this album, written a lot of this album, produced Happy Ending and cowrote a lot of that album, he is a great guitar player, too. Not in the same way. Probably technically better.”

What are you playing these days? You had a Strat with a rosewood neck, did you not?

“I used to. Nowadays, my go-to guitar is a Gibson [ES] 330. It’s the Gibson equivalent of the John Lennon Epiphone Casino, and that has just got an amazing, amazing bark. Incredible.”

There can sometimes be a tension between the guitar and synthesized parts but you worked that well even in the early days. In song like Pale Shelter, in which the guitar has this dry, papery rasp, it worked really well.

“I really like that. We were actually trying to do Blondie, Heart Of Glass, with all the clapping at the end. [Laughs] But yeah, the acoustics, I’m not sure what I was thinking of but it works absolutely brilliantly. It really does. It’s a great combination.”

Nowadays, my go-to guitar is a Gibson 330. That has just got an amazing, amazing bark

You were being too modest when talking about the pioneering aspect of Tears For Fears, because tracks such as Pale Shelter offered a lodestar for how we can pair these two elements. We needed that. Guitar players are quite primitive.

“We are! [Laughs] It is quite an instinctive instrument, isn’t it? It is largely a percussive instrument, the way you hit it. There are obviously people who have gone off the charts with it, with their lyrical expression – like Hendrix – but really it is quite a basic rhythm instrument.”

How has your synth setup changed over the years? Are you someone who scans the internet looking for the next piece of technology, for where the next sound might come from?

“I do buy a lot of the plugins. Things like Native Instruments. I do keep an eye out, and it’s nice to have at your fingertips all the things that the film writers have as well, those sweeping strings, and so I have a lot of that stuff. But it is all on a laptop. It’s on the laptop that I am speaking to you through. It’s absolutely incredible.

“I’ve got drum programs coming out of my ears. I’ve got all the kits, and I spend a lot of time sculpting them as well. For instance, on No Small Thing, that When The Levee Breaks sound is partly the samples from Zeppelin’s When The Levee Breaks but it’s also my own attempt at using the Bonham ambience and ramping up the middle. I keep an eye out, but so much of it is on computer nowadays. It’s crazy.”

And it has completely democratised that production process, the fact that you can buy a VST pack of Abbey Road’s gear arsenal and make an album at home. If we were to lock you in a room, and demand another album, what would you both need to make a Tears For Fears record?

“It would be a couple of guitars, a laptop – obviously – with Logic. I use Logic, with all the plugins, and a keyboard controller. That would be a necessary thing. And the guitars, again, that would be plugging straight into the computer, using all the amp models, which I swear by.

“Charlton is a bit more of a purist in that regard so we end up using another amp modeller that is this big and sits on the desk! [Laughs] But he thinks it sounds better so, y’know… I’m not sure. But most of the guitars on No Small Thing, they are going straight into Native Instruments.”

Do you just let the sound build around that core and keep on going until it’s done?

“It just took a long time. [Laughs] A long, long, long time to get all those parts, because Curt was insistent that there would be singing on the chorus. Originally, the chorus was instrumental and he insisted on singing but thank God he did keep insisting because it sounds absolutely brilliant with our backing singer Carina Round.”

While we were filming the video for Mother’s Talk, Ian and Chris just went crazy, absolutely crazy with Fairlight flutes... Again, I thought, ‘Can we really do this? Can we really go this bombastic?’ Well, yes we can!

There seemed to be something improvisational about how you created those synth sounds in the beginning, messing around with the LinnDrum. It was a strange time because tech was evolving, but perhaps not at the pace of your imagination, whereas nowadays the risk is option paralysis when presented with all these digital tools.

“Yeah, there were a couple of things going on. The moment we had the original Linn LM-1, and you think, ‘Well this is pretty hard to work with in terms of the sounds for specifics.’ It was brilliantly used on Human League’s Dare, and you would occasionally hear them on like a Steely Dan record and you’d think, ‘What the fuck!? How have they made them sound so different, or have they built something around it?’ That was tough.

“When the LinnDrum LM-2 came out it was like, ‘Woah, that’s a bit better.’ Even though it probably wasn’t. And then we jumped at every drum machine that came out. The Drumulator, the E-MU Drumulator, had rearrangeable chips. You’d open the lid put in new chips, [like] When The Levee Breaks, and that’s how that was beefed up like crazy.”

“I wrote Songs From The Big Chair using the LinnDrum. I wrote a lot of the songs by putting in rhythms on the LinnDrum, rhythms from songs that I loved, and rhythms from songs that I trusted, so you are already starting off with a very solid backbone. I thought, ‘Well, if it’s good enough for that song, it’s good enough for any of mine.’ Then it snowballed from there.

“Of course, I couldn’t afford the first Fairlight, or the second Fairlight. Chris had one, Chris Hughes. When Fairlight III came out, £63,000 of your money back in those days, which was a lot of money, I jumped at it of course. I jumped at it, and it was on that Fairlight III that I programmed Woman In Chains and Sowing The Seeds Of Love. That was my next-level instrument.”

You mentioned When The Levee Breaks a few times. Is that Bonham drum sound a signature reference point for you?

“Yeah, it is. And other people have used it, too. I know Depeche Mode used the snare at one point after we had, and that was quite interesting.”

It’s funny, earlier you talking about how chasing hits was a cul-de-sac made me think of what you said about Shout, and how you didn’t see the value in it at first. It is weird how the real creative epiphany is not just the idea but recognising how they might work.

“When you are writing songs you don’t know what the hits are. You have no idea because they are unfinished. Shout was merely a chorus and the rhythm that is subliminal to the Drumulator part.

“So, I had that, I had this fantastic bass drone from the Prophet-5, which was a spitting, almost brass-like sound at the top-end. That’s all I had, that riff and the chorus, and when I took it into the chorus and I sang it, Chris and Ian [Stanley] were like, ‘Oh, Jesus.’

I didn’t really think Shout was a single. I didn’t really think it was anything more than, ‘All we are saying is give peace a chance’

“Ian has said in the past that it was something about how I was singing the chorus that made it really special, but then, yeah, I didn’t really think it was a single. I didn’t really think it was anything more than, ‘All we are saying is give peace a chance,’ on and on and on.

“But while we were filming the video for Mother’s Talk, Ian and Chris just went crazy, absolutely crazy with Fairlight flutes, and by the time I walked back in it was a different track. It was amazing. Again, I thought, ‘Can we really do this? Can we really go this bombastic?’ Well, yes we can! [Laughs]”

Maybe the lesson from Shout is that, when you find yourself asking if something is a little too much, then maybe it is a good idea…

“Yeah, exactly!”

Is trying to pick hits a fool’s errand?

“Well, we’ve never been particularly good at it. Mad World was supposed to be the B-side to Pale Shelter and it was only when I took it into the record company and Dave Bates, our A&R man, said, ‘No, that’s the next single.’ I went, ‘What!?’ That was the first example of the artist not knowing what their best song is. And then it was the toss of a coin between Everybody Wants To Rule The World and Shout.

At our age and with our history, we are far more keen on selling the album, because we think the album is a complete piece of work

“With this album, the record company were talking about going with End Of Night first, which is an obvious pop song. It doesn’t need editing. It’s up. It’s infectious. It’s catchy. Our concern was that it was going to make our job in terms of promoting and interviewing difficult, because it really didn’t sum up the spiritual heart of the record.”

And the idea of the single can obscure that message?

“We purposely haven’t gone with a commercial track yet. The Tipping Point? No Small Thing, that’s clearly an album track. The singles are going to come next – Break The Man, End Of Night, possibly My Demons. There are tons of them, but you never know.

“At our age and with our history, we are far more keen on selling the album, because we think the album is a complete piece of work. We’ll never be able to compete with Wet Leg, who just make these remarkable, catchy songs. We’ll never be able to compete with that. Our medium is the album.”

- The Tipping Point is out on 25 February via Concord Records.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

“Every note counts and fits perfectly”: Kirk Hammett names his best Metallica solo – and no, it’s not One or Master Of Puppets

“I can write anything... Just tell me what you want. You want death metal in C? Okay, here it is. A little country and western? Reggae, blues, whatever”: Yngwie Malmsteen on classical epiphanies, modern art and why he embraces the cliff edge