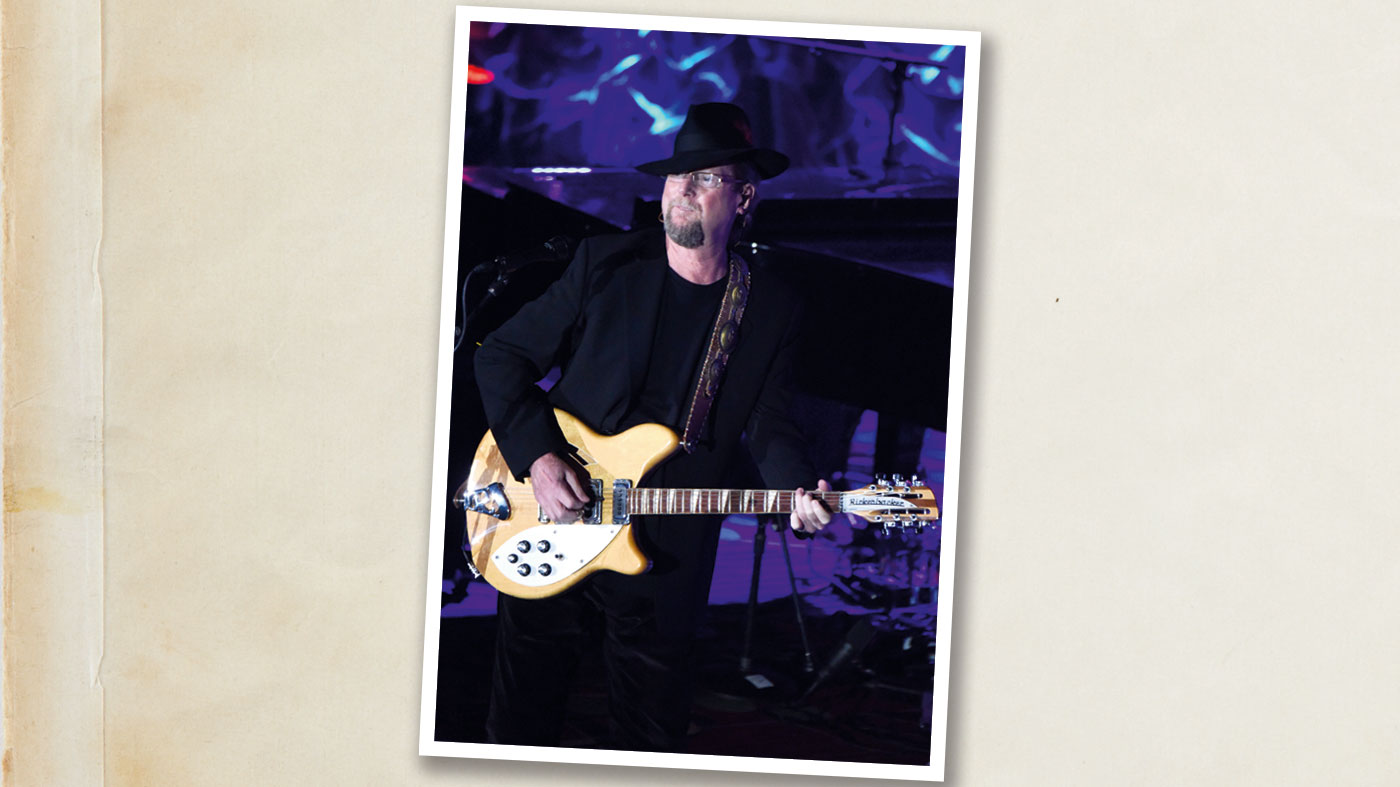

Roger McGuinn on The Byrds' shadow, Rickenbacker tones and going west

In-depth with the 12-string guitar hero

Introduction

We join Roger McGuinn to hear how he the rode the winds from Chicago to New York and finally Los Angeles, where he would cement his signature West Coast sound with that iconic Rickenbacker 12-string jangle…

The jingle-jangle of McGuinn’s 12-string Rickenbacker defined the flood of music that poured from the West Coast in the wake of The Beatles’ US invasion - far more than the relatively conservative (and already old-fashioned sounding) Beach Boys.

We were just finding our way back then as players, when The Byrds were just starting out, but Roger was already there

David Crosby

With a clutch of songs from the formidable Bob Dylan songbook and the vocal blend of McGuinn, Crosby and Gene Clarke perfectly complementing McGuinn’s strident Rickenbacker picking, The Byrds were America’s answer to the Fab Four.

“Roger is an amazing player, just astonishingly good,” David Crosby told Guitarist back in 2014, of his former bandmate in The Byrds. “We were just finding our way back then as players, when The Byrds were just starting out, but Roger was already there.”

Born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1942, McGuinn was bitten by the same bug as many of his fellow rockers when he heard Elvis Presley’s Heartbreak Hotel. At the tender age of 15, McGuinn enrolled in the Chicago Old Town Folk School, learning his craft on the five-string banjo, and would go on to play coffee houses and other stints with some of the big names in folk - The Limeliters, The Chad Mitchell Trio and Judy Collins - before making a name for himself in New York as a guitarist and backup singer for pop star Bobby Darin in the early 1960s.

While Darin gave up live performing not long after recruiting McGuinn, he hired the aspiring songwriter as a staff writer in his offices at the fabled Brill Building. Following sessions in New York for artists such as Simon & Garfunkel, he soon found himself heading west to Los Angeles where the legend that is The Byrds began…

A humble beginning

“My first guitar was unplayable. It was a Harmony and the action was too high; the strings were an inch over the fingerboard. Then my parents bought me a Kay K-161, which was an electric guitar like Jimmy Reed used to play.

“It had an old ‘leopard skin’ pickguard on it and it was cool until I got into folk music and then nobody played electric guitar, so I took all the guitar strings off that and turned it into a banjo - put a nail on the 8th fret and pinned it up with banjo strings and learned how to play the banjo on that.”

Early days on the folk circuit

Lead Belly inspired me on the 12-string. He played a lot of chunky kind of runs and things like that

“By the time I was hired by The Limeliters, I felt pretty confident. I was 17 and I had been playing for three years, so it was a gradual process. Beyond Earl Scruggs, I’d say Pete Seeger and Josh White really inspired me for the blues, and Lead Belly for the 12-string. [Lead Belly] played a lot of chunky kind of runs and things like that.

“If you listen to his 12-string work, it’s a lot of bass notes. He wasn’t that intricate a player, but the way he played 12-string sounded really good and he was an excellent singer. It wasn’t down in the blues range where you hear some of the other blues singers sing; he sounded very melodic.”

The Brill Building

“Guitar playing didn’t have a lot to do with the writing at the Brill Building. When you’re writing a song, you play just chords and play around with them until you get a melody that you can kind of hang some words on. It wasn’t really about guitar there. The guitar was merely a vehicle.

“Plus, I usually wrote with somebody else who would be on the piano. It was just about the chords - I wasn’t thinking about the guitar work at all. I had to develop a formula where I would punch some chords that sounded good and then come up with a melody and kind of hum over that and use nonsense words for a while until it suggested something.”

Trading up his tools

“Around the time I was in The Limeliters I had a Martin 00-21 - like Josh White played - and a five-string long-necked banjo, a Pete Seeger model Vega.

“Then, when I was working with The Chad Mitchell Trio, they wanted me to play a classical guitar, so for that I had a Gibson nylon-string guitar and my banjo. By the time I had started working for Bobby Darin, the sound people wanted to hear had changed again, so he wanted me to play an acoustic 12-string.

I fell in love with that first Rickenbacker, it was great. I practised eight hours a day on it. It’s how I developed my style

“I borrowed one from this guy I knew, but one day I leaned it up against the piano and Bobby moved the piano - it was on wheels - and the piano moved about a foot back and the guitar fell to the floor and the neck broke off. It was a Gibson that somebody had converted from a six-string to a 12-string and it wasn’t braced enough for 12 strings, so it was very fragile and the neck just broke off.

“Bobby went out the next day and got me a Gibson acoustic 12-string. That was the guitar I was playing at the Troubadour [in Los Angeles] when I met Gene Clark, and that was the guitar, along with my banjo, that I traded in when I got my first Rickenbacker.”

The West Coast sound

“I fell in love with that first Rickenbacker, it was great. I practised eight hours a day on it. It’s how I developed my style. Plus, it sounded great even without an amplifier. I didn’t have an amplifier in the hotel where I was living, I just played it in its semi-acoustic form and it sounded really good.

“It had a very, very mellow kind of silky sound, so I had a lot of fun learning how to play with that. I had to develop a different style, because the narrowness of the neck wouldn’t allow you to play an A chord with three fingers - you had to play it with two fingers. And it was the same thing with the E minor chord; I played that with one finger, too, so I had to develop a different fingering method.

“My first two Rickenbackers were stolen. Not long ago I saw one of them for sale in Las Vegas for $750,000. It was kind of funny - to me, it was just a $600 guitar. I’m not really much of a collector, anyway. I have a few guitars, but they’re mostly just tools to me. I don’t get sentimental about them.”

City of angels

“When I first visited Los Angeles on tour, it was a sleepy place. It had the movie business, but as far as the music business went, there wasn’t much going on.

“When I came back in 1964, the Beach Boys were popular, as were Johnny Rivers and the Walker Brothers. It still seemed sleepy to me, though, having lived in New York, listening to WMCA and 1010 WINS and WNBC, and all the great radio stations where the DJs talked a lot faster and the pace was a lot more intense. Los Angeles was like a little cow town to me! It felt like there was nothing going on.

I didn’t use any pedals or anything - I plugged my guitar into a Vox amp and played it

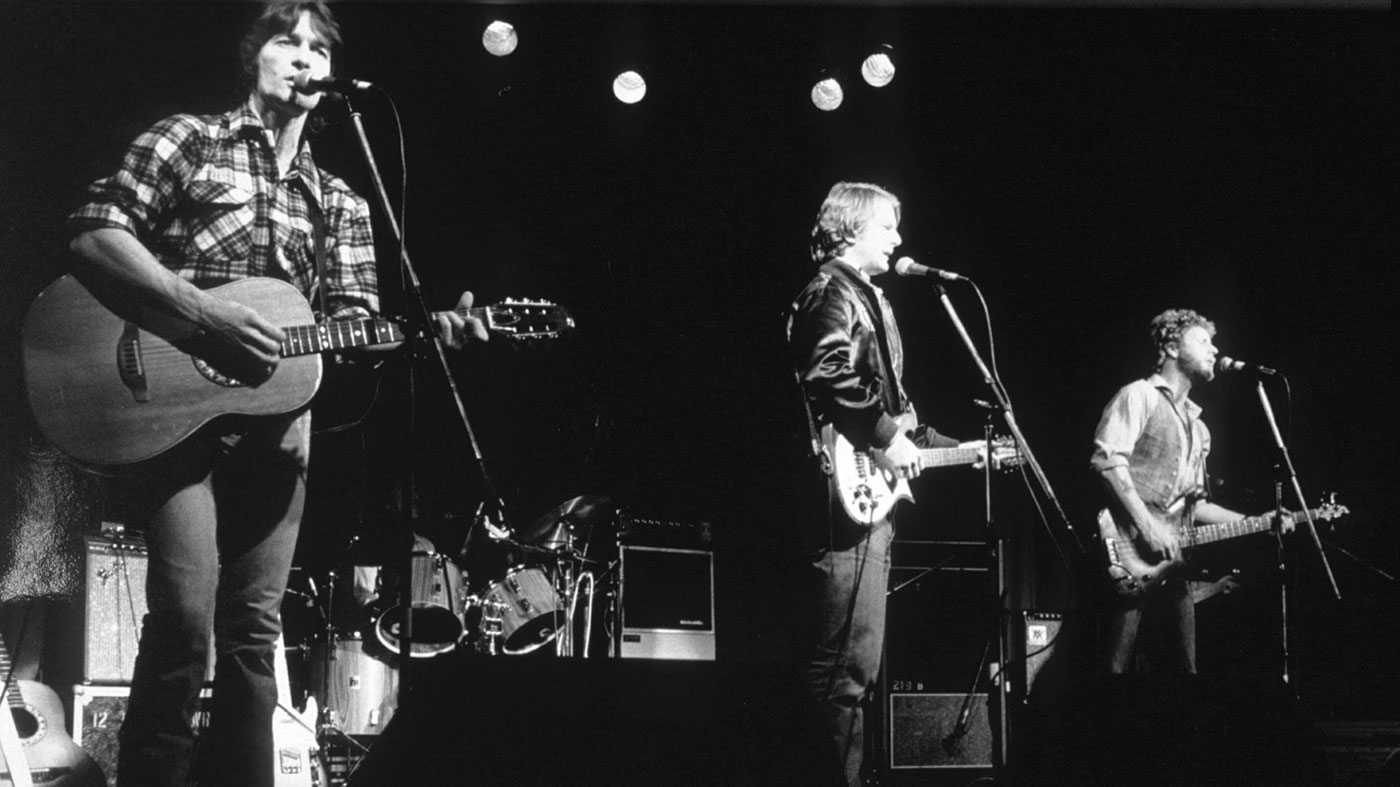

“I went up there initially to open up for Hoyt Axton at the Troubadour, and Roger Miller was on the bill. Gene Clark came and heard me doing some Beatle-y stuff and thought it was cool. He came up to me after and wanted to write some songs, so that was the beginning of it.”

Future SoCal community

“I remember seeing Jackson Browne there, and he was having a tough time with the audience. He came offstage and said to me, ‘Man, they say New York is a hard place to play, but this is much harder.’ I saw Joni Mitchell there before she became popular, and I remember watching the guys that turned into The Association - who were called The Men at that point - and the Modern Folk Quartet. I saw Barry McGuire and Barry Kane, who had a duo called Barry & Barry, and then there were all the people that turned into the Christy Minstrels, it was such a good scene.

“It was more of a commercial folk club than the Ash Grove, which was on Melrose. That was more Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee and much more ethnic stuff. I used to go to the Ash Grove and, being a musician, I could get in free to either place, but I enjoyed them both for different things.”

Byrd sounds

“I didn’t use any pedals or anything - I plugged my guitar into a Vox amp and played it. In the studio, our engineer, Ray Gerhardt, used UA LA 2As for compression on my Rickenbacker, but on stage I didn’t have that, so I took a Vox Treble Booster and I built that into my guitar. I got the idea from Paul Kantner from Jefferson Airplane, who gave me one. That gave the guitar a little more sustain and it made it really screechy.

“At one point, I did take a phase shifter on the road and used it for a tour, because it was a new invention at the time and I was just playing around with it. But I decided a Rick sounds better without it. Later, for live stuff, I used Fender Dual Showman amps, but in the studio I didn’t use an amp. I went into the control room and plugged into the ’board, it gave me more tonal control.”

The last flight

“[With The Byrds], it was a tour/album/ tour treadmill. But it’s hard to complain, because Columbia Records was very hands-off.

“They never pushed us in any direction. I mean, they let us do Sweetheart Of The Rodeo and they let us do Farther Along. Whatever we wanted to do, we did. And so we had that same kind of freedom to fail - and we did!”

1973-1977: the solo period

I had the shadow of The Byrds; you can’t get over that. Once you’re in a band you’re kind of buried

“There was some good stuff on my solo albums. Unfortunately, it wasn’t consistent and I never really got traction as a solo artist. Those records didn’t make any money, although the music is good. I had the shadow of The Byrds; you can’t get over that. Once you’re in a band you’re kind of buried. So, eventually, I just gave up the idea of making new rock ’n’ roll records for public consumption.”

The road ahead

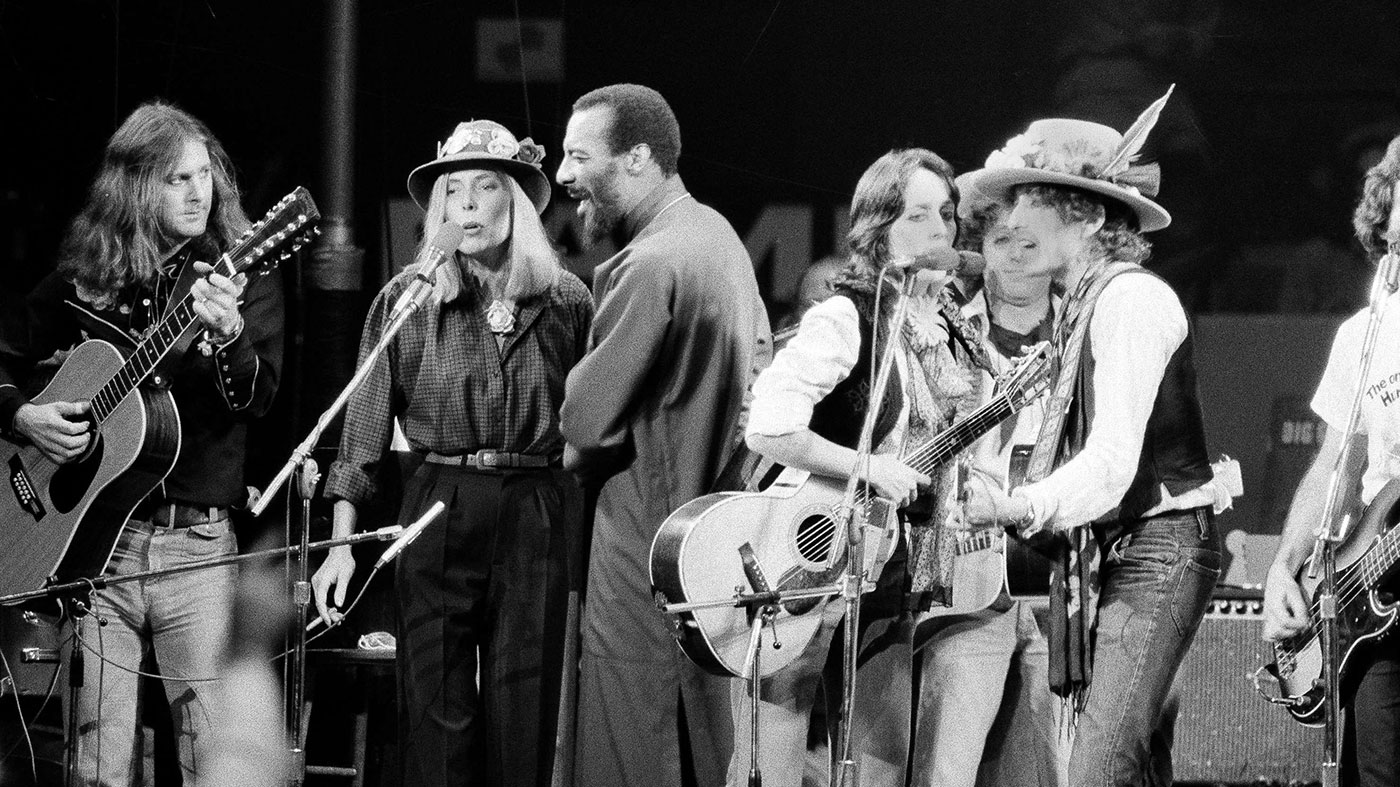

“When I was playing on Dylan’s Rolling Thunder tour [1975 to 1976], Ramblin’ Jack Elliot was on it and he said, ‘You know, Roger, some of the best fun I ever had was when I hit the road with a guitar and just played wherever they’d have me.’

“And I said, ‘Yeah, that sounds great.’ So, my thing with Gene and Chris [as McGuinn, Clark & Hillman] faded out, I came back home where I was living with my wife, Camilla, and I said, ‘You know, I’d like to go on the road solo.’ And she said, ‘Well, that’s great. Call up venues and see if they’ll book you like that.’ And I did.

“That was back in the 80s and we’ve been doing it like that ever since. I really wanted to be a solo artist and just never quite got the chance. But that’s what I wanted to do, to be solo.”