Classic interview: Robbie Robertson on The Last Waltz, his bronze Strat and playing in the eye of the storm with Dylan – "On that tour in 1965 and ’66… I have never heard of anybody going through something like that, ever, in music history"

A 2017 Guitarist magazine interview with the late guitarist found him looking back on making history

From backing Bob Dylan at the epochal moment when he ‘went electric’, to carving out woody, jagged guitar lines in The Band, the late Robbie Robertson's playing is part of the fabric of American rock.

Guitarist magazine caught up with with him in 2017 to talk about the bronze-coated ’54 Strat that he used on the night that Dylan, Clapton and Muddy Waters joined him on stage for five straight hours - along with Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Dr John, Van Morrison and, well, nearly everyone who mattered in '70s rock - the fabled Last Waltz…

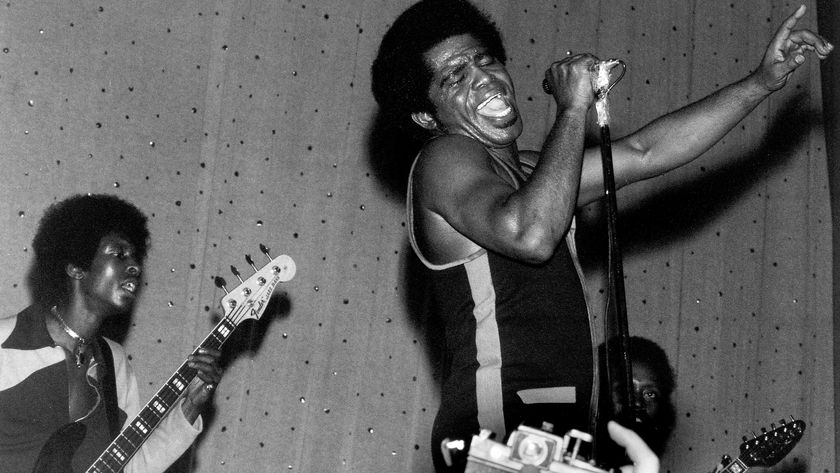

On 25 November 1976, Robbie Robertson and The Band performed a gig at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco that closed - but also crowned - an era. The gig marked the end of a touring career that had covered untold thousands of miles. He’d played guitar at Bob Dylan’s side in ’65 when irate fans stormed the stage in protest to their folk hero going electric. As a core member of The Band, he cut a legendary debut album at The Big Pink, a house in New York, and then carried The Weight all the way to Woodstock in ’69.

A terse but soulful player, Robbie favoured Teles throughout his early career, but later found his ideal match in a ’54 Strat and a Tweed Twin. We join Robbie to talk about the guitar’s role in that momentous gig, which was filmed by Martin Scorsese, the Strat’s recent recreation by Fender Custom Shop Master Builder Todd Krause, and Robertson’s memories of what went down during the greatest live show of the '70s.

Let’s start with the bronze Strat - where did you first come by it?

“I got the guitar from Norm’s Rare Guitars in Los Angeles. Norman Harris always had spectacular guitars. This was one that he brought me. It was originally red, which was kind of unusual, because the guitar is from 1954. The serial number is 0234.

“Anyway, he brought me a bunch of guitars to try out. In that batch, there was a Telecaster with a V neck. It was beautiful. I had played Telecaster for years, starting back with Ronnie Hawkins, because we had to play long hours and it was one of the lighter guitars. It didn’t hurt your shoulder at the end of the night. Anyway, I was drawn to this Telecaster, and I played it and it felt really good. This V neck was great on it.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

There was something about the neck on it, the balance

“Then he brought out this Stratocaster. I had played a Stratocaster years earlier, but because of the tremolo bar on it, and the way that whole thing works, if you break a string it goes wildly out of tune. The tremolo bar also makes it hard to keep in tune as well. I just didn’t want to be bothered with that.

“So I veered away from Stratocasters and went in the direction of the Teles. But when he gave me this guitar to try, it felt amazing. There was something about the neck on it, the balance. And when I plugged it in, the sound. It just completely swayed me in that direction. I said, ‘I am going to take this Stratocaster, and I want to show this Telecaster to Bob Dylan, because I think this would be great for him.’

“We were planning on doing this tour in the beginning of 1974 with Bob Dylan and The Band. I just said, ‘I loved this Telecaster.’ Anyway, Bob ended up getting that guitar and used it for that whole tour. I used the Stratocaster for that tour. I used the Strat almost exclusively after that. It had such a great feel to it.”

At what stage did it acquire its unique bronze finish?

“Well, in 1976 we decided to do this Last Waltz concert, because it was a culmination of something. It was the end of some era; it was the end of a relationship with the road that I had had since I was 16 years old. I was just trying to think of what to do in celebration of this.

“I didn’t know whether it would be a bad idea, but I decided to have the Stratocaster bronzed. It was a bit tricky, you know, finding somebody to do that. One of the road manager guys said, ‘There is a place where they bronze baby shoes’ - it was some kind of a tradition that people would take their baby shoes and dip them in this thing and bronze them.

“He said, ‘I might be able to take it to this guy and see if it is too big, the body of the guitar.’ Anyway, he did some research, took it, brought it back and it was bronze. I thought, ‘Wow. It really does look beautiful.’ They put it all back together again. I played it and it sounded different. It sounded different and unlike any guitar that I had ever played before.

“Then, when I stood up – you know, I put on the strap – I realised it weighed more, too. I was trying to figure out whether this was an advantage or disadvantage, the different tone that the instrument was giving off.

“I tried it out in the rehearsals we were doing for the Last Waltz with the band and with some of the guest artists. It started to feel right to me, and I was quite drawn to the tonality of it. There was a little bit more… it was just a sharper tone, with more metal involved. I liked it. It grabbed right onto the notes and it made them sting, in a way, and have a nice sustain to it as well.”

What’s the tweed amp that you used in the background of the footage?

I have actually compared the new version and the original in the bronze that Todd Krause at Fender made. They are remarkably similar

“It is a Fender Twin. I still have that amp. I still have that guitar. There are some collectors that are trying to buy it from me, as we speak. But it is kind of priceless, do you know what I mean? The guitar has lived.

“I have actually compared the new version and the original in the bronze that [Master Builder] Todd Krause at Fender made. They are remarkably similar. My son, Sebastian, who is kind of a guitar aficionado, was trying out the instrument. He was comparing it to other Stratocasters and guitars and said it is the best-sounding guitar he has ever heard in his life. He said it is truly remarkable.”

You mentioned earlier that it’s quite unusual in that it is a ’54 that didn’t appear to be a sunburst but came to you finished red. Was that a flat red, or more like the Candy Apple metallics that came later?

“You know what? It seemed to me that it was somewhere in the middle. That it wasn’t high glossy gloss and it wasn’t flat. It was just right. It didn’t look too shiny and it didn’t look dull. It looked sexy.”

Well, that is what a guitar should be, right?

“We hope.”

In the film, you brought out a modded sunburst Strat when you were trading solos with Eric Clapton on Further On Up The Road. That also looked interesting…

“Yes, it was one of those [two-tone] sunbursts with no red in it, which I always preferred. It was just brown and yellow. It inspired a guitar, this Robbie signature that Fender has made, which is called a Moonburst, because it has a different look and a different tone to it. It is more nocturnal.

I ended up giving it to Martin Scorsese as a gift for doing The Last Waltz. He has it in a glass case in his house in New York

“I got that guitar because it didn’t have a tremolo bar on it. The back bridge there was flat [hard tail], so it didn’t go out of tune. I can’t remember if I broke a string, or I did something on the bronze one that just made it go extremely out of tune, so I just switched it out for this guitar, which I had as a backup. But it was also an amazing guitar.

“I ended up giving it to Martin Scorsese as a gift for doing The Last Waltz. He has it in a glass case in his house in New York.”

The bronze Strat has quite an unusual pickup layout. How is it wired up differently to standard?

“On most of my guitars I have had the middle pickup moved and wired in with the rear pickup to make the back pickup be a little fuller. On some of them, the two pickups became like a humbucking pickup and it just had a thicker tone to it.

“I tried it without them being wired together, too: the middle pickup was just moved to the back and there were still these other positions on the toggle switch. Now, the toggle switch in the front is the same. In the middle, it is all of the pickups. In the back, it is just the back two pickups. I did that because I found the middle pickup would get in my way.

“Some years ago I used to use a flatpick and two metal fingerpicks, and for that it really got in the way. I thought, ‘God, I don’t know. Maybe this doesn’t bother anybody else,’ but for whatever I was doing, it got in the way a little bit. Then I thought, ‘I could accomplish two things here. I could get it so it isn’t in the way, and also so the back pickup is fuller sounding.’”

You get a lovely sort of drive sound or a crunch sound through most of the gig. Is that just off driving the amp naturally with the volume? Or did you have any pedals in the signal chain?

Buddy Holly me, he said, ‘I have got this Fender Twin amp. I blew one of the speakers and it sounded better so I didn’t fix it. That is how I get this sound’

“Well, when I was very young, 12, 13 years old, I met Buddy Holly. And I asked him how he got that sound: he played a Stratocaster into a Fender amp. And he told me, he said, ‘I have got this Fender Twin amp. I blew one of the speakers and it sounded better so I didn’t fix it. That is how I get this sound.’

“He said, ‘Down in Texas, and some places in the South, people actually will cut one of their speakers to get that sound. Or, sometimes, they will put paper in the back of the speaker so it would vibrate and rattle and give more of a distorted sound.’

“I thought he’d just told me the Holy Grail. Anyway, eventually, I got a Twin amp with the two 12-inch speakers in it and just from use, my speakers got worn. They got broken in, almost broke. It made that sound. Like I said, I still have that amp in my studio and it still has that sound. When somebody else would think, ‘Oh my goodness, maybe I need new speakers,’ I just thought, ‘They’re now sounding the way they should.’

To what degree were you conscious of Scorsese filming the gig while you were playing?

The film was the last thing we were thinking about

“Well, for the most part we were so busy trying to get it right, trying to play our songs as good as we have ever played them - not wanting to let down all of these different artists, these guest artists we had. When you have to go from playing with Muddy Waters to Joni Mitchell, it is quite a spectrum.

“The film was the last thing we were thinking about. We played over 20 songs with all these artists that we had barely any time to run over. People don’t realise that, because you don’t want to make it look like you’re struggling with this kind of thing.

“To me, it was Guinness Book Of Records. The fact that we could play with all of these different artists, from Dr John to Neil Diamond… We never screwed up once the whole night. We did the whole thing and aced it. But it was because of focus and concentration. There was no time to be thinking about filming.”

What moments stand out in your mind most from the gig?

“I certainly got a thrill with Van Morrison. He raised the bar and we played that song, Caravan, with all our heart. I can’t remember much of it that wasn’t a thrill, actually. Playing Such A Night with Dr John was just a big grin. Muddy Waters was another one of the highlights.

“Of course, with Eric Clapton, who to this day is still a dear old friend, you know what I mean? I don’t know if there was any downside. Joni was as cool as can be, and Neil Young, oh my God, doing that song Helpless, what a moment that was. He did it so well.

“Of course, there was also Bob Dylan or Ronnie Hawkins, who were the guys we started out with - the entire band did. It was always challenging with Bob: that night we weren’t even sure that the songs that we had said we were going to do were the songs that we would end up doing. That was always keeping you on your toes. But playing with Bob was like second nature to us at that point.”

The Band backed Dylan during the transition from being a folk icon to a rock ’n’ roll artist, which was very controversial at the time. What mark did that leave on your own musical personality?

I thought, ‘If Bob can do it, I can do it

“Well, on that tour in 1965 and ’66… I have never heard of anybody going through something like that, ever, in music history. The idea that we played all over North America, all over Australia, all over Europe, and people booed us every night, sometimes threw stuff, sometimes charged the stage.

“It was challenging. To be able to do that and go through it… But I thought, ‘If Bob can do it, I can do it,’ you know, so it was an extraordinary experience to be playing music and thinking, ‘We are right and the world is wrong.’

“It was a phenomenon. Somewhere in the middle of that tour I realised that we were in the midst of a musical revolution. Because you start out, people boo you every night - normally, a group would say, ‘Maybe we are doing something wrong.’ But we never budged. Bob didn’t take one step back. I admire him so much for standing his ground.”

You could have faced anything after that, presumably?

“That’s how I felt. When The Band made Music From Big Pink and went on as The Band, people said, ‘What the hell is this? Where did this come from?’ But we had been together for like six or seven years before we made it. It was because we’d already done our woodshedding. We had paid some dues, to say the least.”

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.

“The solo is very recognisable and crucial to the song”: How Chappell Roan’s former touring guitarist handled the Pink Pony Club guitar solo live on stage

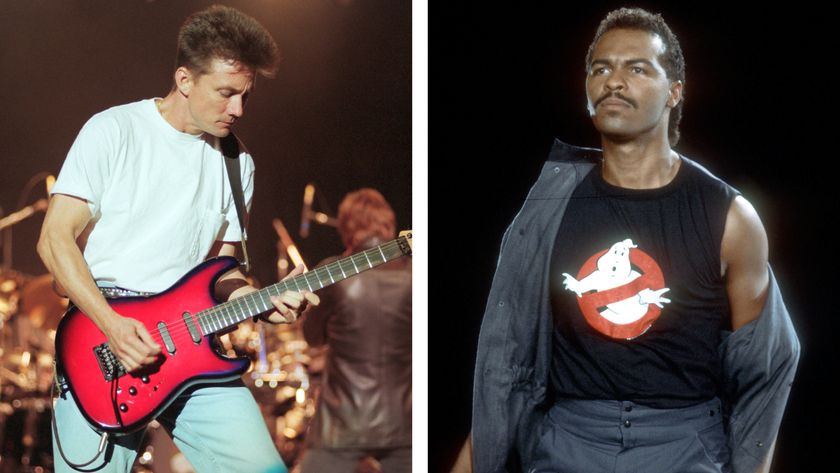

“I am under an NDA, but I think everybody knows what happened”: Former Huey Lewis and the News guitarist Chris Hayes on that Ghostbusters plagiarism dispute