The producer's guide to the Roland RE-201 Space Echo: "It can cover everything from simple saturation to wild, out-of-control and bizarre self-oscillation"

Here's how to master one of music's most beloved effects boxes, used by dub producers and experimental electronic composers alike since the early ’70s

Roland, of course, has a huge and diverse history of producing classic products, from Boss pedals, to era-defining synthesisers and drum machines. One of the company’s earliest releases, however, perhaps doesn’t grab the headlines as much as the Basslines and XOX beats, and that is the Roland RE-201 Space Echo.

This tape-based delay and spring reverb was produced by Roland in the 1970s, and has appeared on countless recordings thanks to a sound that could cover everything from simple saturation to wild, out-of-control and bizarre self-oscillation.

Really, though, its dub delays and rich reverbs have become its defining characteristics. With 12 modes of operation and some fairly basic controls, it was (and is) a very easy-to-use device. You can simply switch modes to explore combinations of three tape heads and spring reverb, tweak bass and treble and both echo and reverb volume, or drive the unit wild with Repeat Rate and Intensity (feedback) controls.

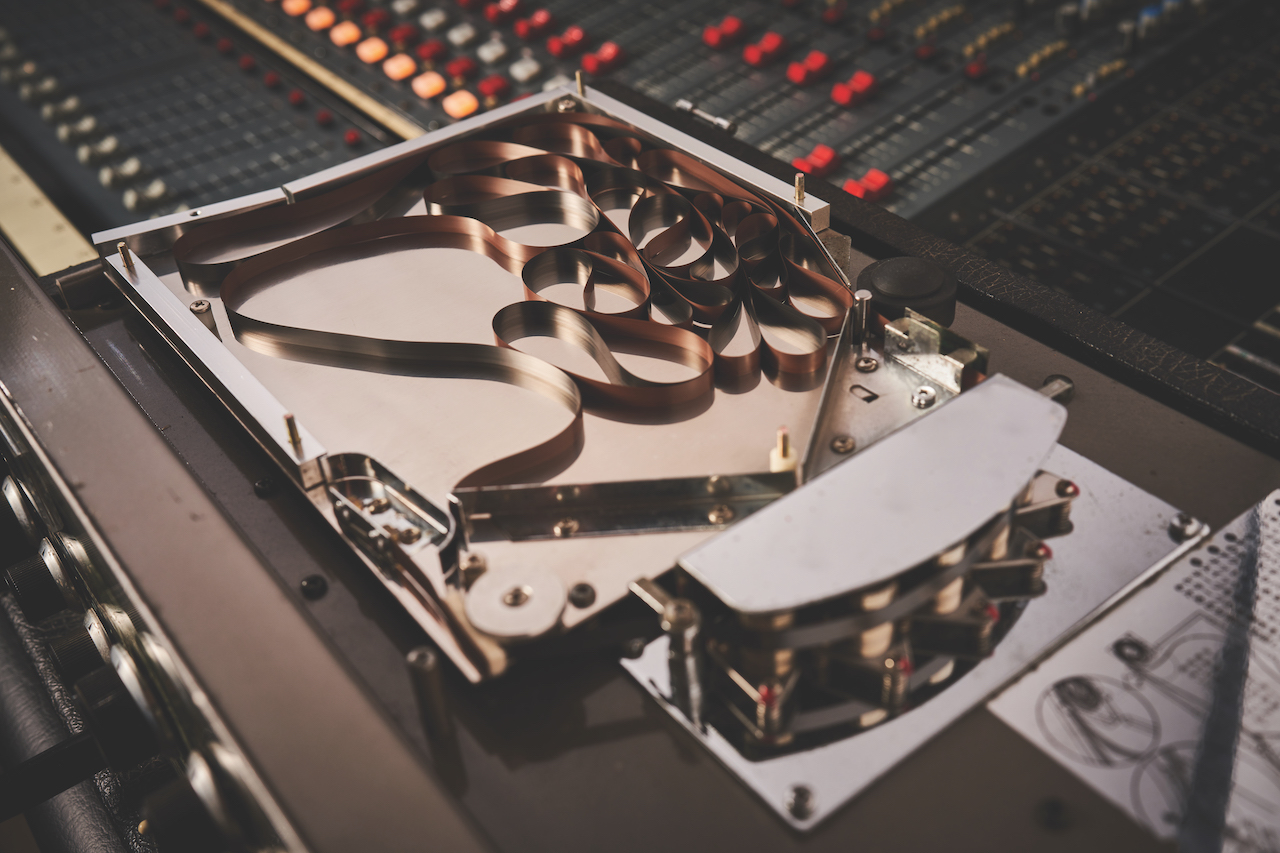

The unit has two mic inputs, plus PA and instrument line-ins so its flexible connectivity meant it was both a live and studio favourite. Lift its lid and you will see its distinctive tape spooling in operation under a glass cover as it processes your sound, which is truly a site to behold.

Here’s how this quirky, characterful, and lovely-sounding delay and reverb carved its place in music production history.

A brief history

Roland was founded in April 1972 by Ikutaro Kakehashi and, in its first two years, released a wide range of products that would set a precedent for the next five decades. There were drum machines (TR-33/55/77), synths (the SH-1000 and SH-3), pianos, guitar pedals, and, in 1973, two delays, the RE-100 and RE-200 tape echoes.

Roland was attempting to cash in on the popularity of the tape delay, which was based around tape loops and had been a popular effect since the 1950s. These were pretty simple: a recording head recorded what you played, and a reading head played back the delay.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The RE-201 became the delay to own. Famous users included Bob Marley, King Tubby and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry

Loop it and add feedback and you have several delays. However, tape delays were fragile, so Kakehashi attempted to build more stable systems, but didn’t realise this true goal until a year later with the follow-up models, RE-101 and RE-201, which also adopted the ‘Space Echo’ name.

These were both sturdy and affordable. Other delay units would use loops and two reels like a recorder, but these employed a single tape loop with a much longer length, with the tape spooling into the chamber above the unit and able to create much longer delays. With its extended feature set, which included the 12 modes and a spring reverb, the 201 became the delay to own.

Famous users included Bob Marley and producers like King Tubby and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, who would exploit the Intensity control to create organic delays and swelling effects used in reggae and dub. The likes of Radiohead, Portishead, David Bowie, Nils Frahm and Pink Floyd have also used the machine’s tape speed and delay rate controls to create all sorts of pitch and oscillation effects on many recordings.

The Space Echo was a big hit, then, and continued to be produced in various forms like the RE-301, RE-501 and SRE-55, until 1990.

Modern models

In 2007, Roland re-introduced the Space Echo in pedal form with the Boss RE-20, which featured many of the original features in a diminutive twin pedal design. The latest incarnations of this are the Boss RE-202 (£299) and RE-2 (£179).

The RE-2 is the more compact version, offering core Space Echo features like the three-head configuration and 11 modes. The RE-202 has three footswitches and extended features like extra delay time, a tap tempo control, memories for presets, and a fourth tape head for extra flexibility. Unlike the mono original, both Boss pedals offer stereo i/o.

Other modern hardware devices that offer the Space Echo sound include the Universal Audio UAFX Galaxy Tape Echo & Reverb pedal (£279), the NUX Tape Echo pedal (£179), and the more boutique Echo Fix EF-X2 (£1,760).

Software emulations

Software is a great way to get the Space Echo sound, and you are spoilt for choice here. AudioThing’s Outer Space ($69) offers a heap of Space Echo vintage goodness and adds extras like a Ducking control and Pre-Emphasis filter. Even cheaper is Cherry Audio’s Stardust 201 ($29), which includes the chorus from the original RE-301. Genuine Software’s GS-201 MkII also has that chorus for €45 plus tax.

Universal Audio’s Galaxy Tape Echo is costly at £199, but likely offers the truest original experience

Of the bigger developers, IK Multimedia’s Space Delay is expensive at €99, but adds lo-fi effects, filters and ducking. Universal Audio’s Galaxy Tape Echo is even more costly at £199, but likely offers the truest original experience, knowing UA’s component modelling as we do. Finally, Arturia has the €99 Delay Tape 201, which is a great rendition with both original features and modern tweaks.

Freeware versions are surprisingly rare, but include Dream Vortex Studio’s PC-only Space Echo. But Valhalla’s Supermassive is always a good free bet to cover any delay requirements and has just been updated with more models.

So there’s more than enough modern hardware and software to create the Space Echo Sound, and if you want an original, there are a large number still around – not that surprising given how well they were built – but expect to pay at least four figures for an original machine.

How to use the Roland RE-201 Space Echo

Here’s a quick rundown of the main controls on a Space Echo. We’ve already covered the connectivity – the main dials on the left control levels for all inputs – and the EQ controls are self-explanatory. The Reverb Volume is simply a mix control for the spring reverb, a lovely sounding effect on its own, and the 12th mode on the device, at the ‘6 O’clock’ position on the Mode dial.

For the remaining controls, the Repeat Rate dial simply controls the length of time between the input sound and its repeated sound by speeding up or slowing down the tape. Doing this during playback affects the pitch, introducing fairly wild, real-time effects, and is one of the joys of using a Space Echo.

The number of repeats is controlled by the Intensity dial (or Sustain), which controls a feedback loop. At a minimum you get the single repeat; at maximum the repeats go on forever, sending the Space Echo into self-oscillation. Finally, Echo Volume is the echo mix control; set dry and you won’t hear the delay, or set it to full Echo and you’ll only hear the delay for a ducking-like effect.

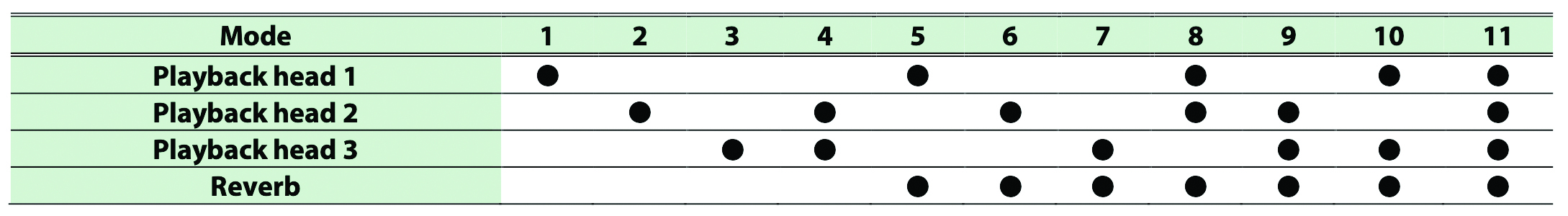

There are three tape playback heads on the Space Echo, another feature that gives it its unique character. These are equally spaced so they each add an equal delay time to the original input signal. So if this original tape delay time is one second, the second is at two seconds and the third three seconds; or, to put it another way, the delay times for playback heads 2 and 3 are two and three times the delay time of playback head 1.

This table (Fig.1 above) from the boss RE-2 manual shows the tape head configurations for 11 of the 12 modes of the Space Echo, the 12th being reverb on its own, as mentioned above. It’s pretty simple to understand: the first four settings are echo only, each of the first three employing each tape head for a single delay at ever-increasing times.

Mode 4 is a combination of playback heads 2 and 3. The next three modes are again single echoes on playback heads 1, 2, and 3, but this time adding the spring reverb. Modes 8, 9, and 10 are combinations of two playback heads with spring reverb, and mode 11 is all three playback heads with spring reverb – the Space Echo on max!

And there you have it – the Space Echo unleashed. The best way to appreciate it is to start in mode 1 with a single delay and experiment, which is pretty much what we do in the tutorials below as we cover some of the main effects you can achieve. You’ll quickly realise why the Space Echo holds a special place in so many producers’ hearts and studios.

6 effects to create with the Space Echo

You can employ the Space Echo to get some varied, classic sounds. We’re using the Arturia Delay Tape 201 here, but you can use these settings on any Space Echo emulation or even the hardware if you are lucky enough to own it.

1. Delays 1, 2 and 3

Create a simple melody loop in your DAW, and set the Repeat Rate at a fairly low and slow value – around a third up – then the Echo Volume at maximum, Intensity at zero, and everything else at mid. Dial through modes 1 to 3, and you should hear the single delay get longer as you step up.

2. Saturation with two delays

In mode 4 you get two tape playback heads. Push the Input Drive up and you get lovely saturation on the input signal, but note that it only affects the repeated delays, both of which (from playheads 2 and 3) should be very obvious to hear now.

3. Going pitch crazy

Now play with the Repeat Rate dial while your melody is looping for some of those crazy pitch effects we mentioned. Note that on the Arturia you get left and right options, as it’s stereo. The original has one dial.

4. Instant dub

The Intensity dial introduces wonderful feedback into the delay, so set this at around half and you introduce a lovely simple dubby feel. Combine this with some automation of the Repeat Rate, and you can tame some wild pitch effects.

5. Haunted dancehall

Now we’ll introduce some amazing spring reverb in mode 8, so keep all settings as they were, but dial up the reverb mix for a very haunting dubby vibe. This is the Space Echo in its full glory.

6. Infinity and beyond

Finally, you might not expect the full-intensity dial to go on forever, but set it at maximum, play your loop, and then stop… and it does! You can even play with the rate dial for pitch effects as your delays swell up and down. It can get pretty mesmerising.

Andy has been writing about music production and technology for 30 years having started out on Music Technology magazine back in 1992. He has edited the magazines Future Music, Keyboard Review, MusicTech and Computer Music, which he helped launch back in 1998. He owns way too many synthesizers.