The producer's guide to the Pultec EQP-1: "Its beauty lies in the the extraordinary character you get when you disobey what you’re told to do by the manual!"

This 1950s EQ is still one of the most in-demand processors around, so much so that you can find many (many) hardware and software emulations. But just why is the Pultec EQP-1 such a revered machine?

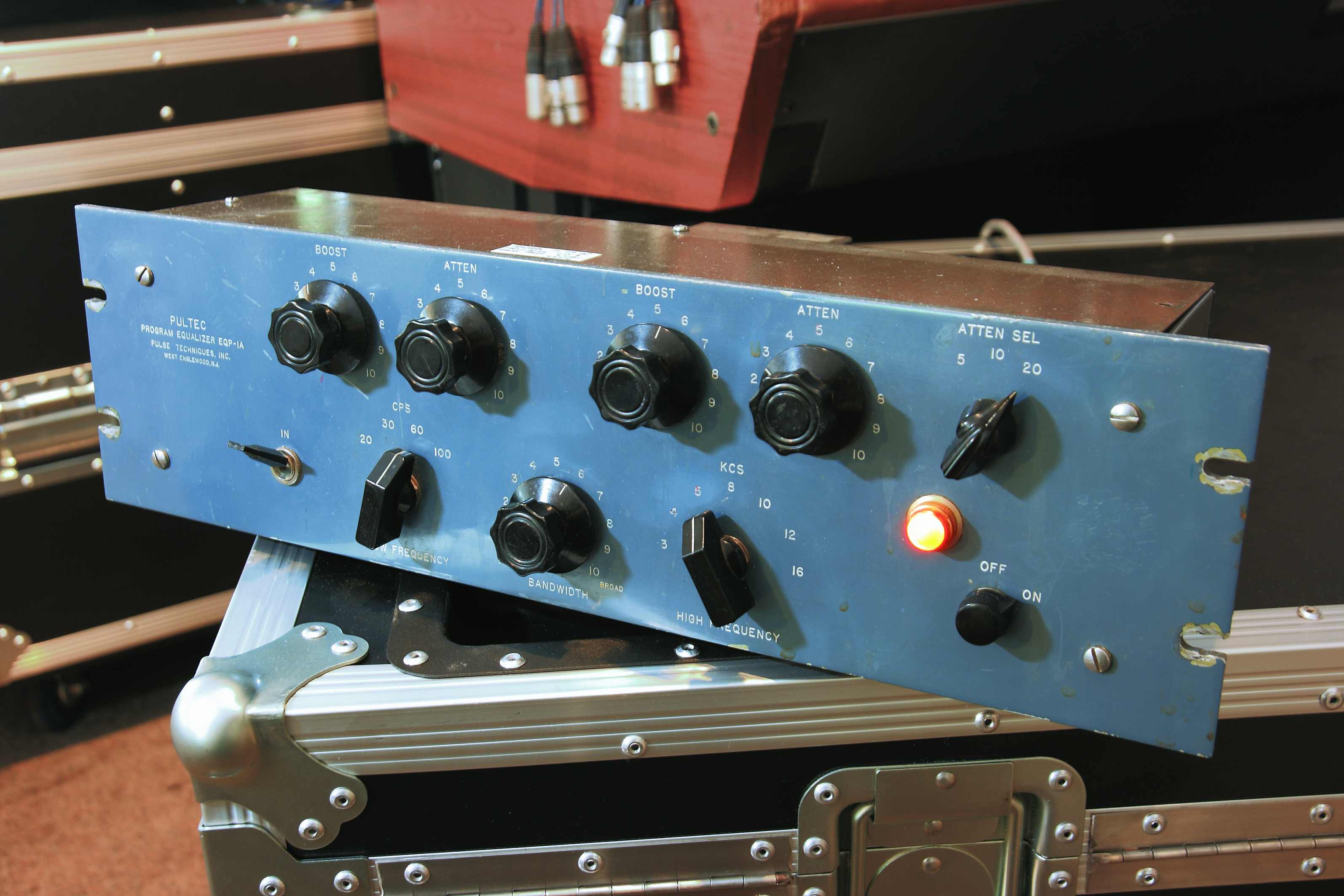

The legendary passive EQ, Pultec EQP-1, is one of the most sought-after pieces of vintage hardware. Original units can easily fetch well into five figures – on the rare occasions that they come up for sale – and even many newer hardware versions can cost up to £5000. Fortunately, as we shall see, there are plenty of both hardware and software alternatives.

The EQP-1’s beauty lies in a combination of simple operation, its broad sweeps of frequency cutting and boosting, an ability to impart an almost indefinable presence on whatever signal you put through it, and the extraordinary character you get when you broadly disobey what you’re told by the manual!

The original EQP-1 was a ‘program’ EQ, so designed more for wide bandwidth mix EQ-ing, but it works as well on individual tracks. The sonic character comes from the unit’s original passive design – or indeed an upgrade to it. The original passive structure meant a loss in signal as the attenuation or boosting took place, so the later EQP-1A added a 16dB tube gain stage to make it lossless, and it’s this tube colour that gives the 1A a distinct sound, whether you use it as an EQ or not.

However, the EQP-1’s EQ character is something else too. On the face of it, the unit is a simple EQ, with low and high-frequency shelving EQs, frequency bands to select within each range, and dials to boost or attenuate these bands. While the unit has a bandwidth, or Q dial, however you boost or cut, you get a smooth, characterful result.

The most famous EQP-1A use, however, is ‘the Pultec low-end trick’ which we’ll detail later, where you go against advice in the manual and boost and cut the signal at the same frequency. Rather than these dual operations canceling one another out, a characterful sound emerges, great for any low-end sounds.

A very brief history

Like many pieces of today’s sought-after studio gear, the Pultec EQP-1 was first developed back in the 1950s when recording studios were in their infancy, just welcoming the sounds of rock‘n’roll. And like many early studio tools, if you were first to market, your reputation would be sealed for decades to come.

The Pultec EQP-1 was the first passive EQ, so did not initially require power for its specific frequency signal boosting or attenuation. It was designed and hand-built by Gene Shenk and Ollie Summerlin in Teaneck, New Jersey, USA. They had met while studying electronics at the RCA Institute in New York, after which Gene worked for RCA and Ollie worked in the navy, before becoming an engineer at Capitol Records.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Shenk and Summerlin joined forces to form Pulse Techniques in the early ’50s, and after initially focusing on electronic components, they made their first EQP-1 in 1956 (some say as early as ’51, but the company wasn’t founded then). In 1961 they released an updated version, the EQP-1A, which featured that make-up gain tube stage we discussed earlier, modified low-end curves and extra high-end bands, and this is the Pultec most emulated in hardware and software today.

There are probably more software emulations and hardware clones of this EQ than any studio gear ever made

The EQP-1A became a studio favourite across the world, and several other units were added to the range over the following years, including the 1971 EQP-1A3, a smaller 2U version.

Pultec also moved away from tube-based EQs, producing a solid-state version, but this was not seen as being anywhere near as characterful as the tube-based unit. Other variations included the EQP-1A3S, EQP-1R, EQP-1RS and the MEQ-5 – this latter EQ is also modelled in various software emulations as the mid-range Pultec.

In 1981, Shenk decided to sell the business, but when no buyer could be found, the original Pulse Techniques closed its doors. That wasn’t the end of the story, though, and after acquiring the rights to the name and getting advice from Gene Shenk, electrical engineer and materials scientist Steve Jackson decided to start Pulse Techniques LLC in 2000. He began manufacturing an as-near-as-can-be identical EQP-1A, along with other Pulse Techniques gear, and there are now half a dozen variations of the EQ available, selling for up to £5,000 a unit.

Software models

As well-crafted as the original hand-built Pultecs were, there are very few available to buy secondhand these days. But it’s a testament to how well-regarded these original units are that there are probably more software emulations and hardware clones of this EQ than any other piece of studio gear ever made.

On the software side, you’re spoilt for choice. Of course, the big guns of Waves and Universal Audio, who specialise in meticulously recreating old gear, are among the best. Waves’ PuigTec bundle includes emulations of both the EQP-1A for your highs and lows, and the later mid-range MEQ-5. And while both are advertised at $299, big discounts are frequently available.

Universal Audio’s Passive EQ Collection is almost identical in scope and price, offering both the EQP-1A and MEQ-5 for £299, and to hear ‘the magic’ in action, UA has some great videos of the Pultec, including the MEQ-5 adding a lovely depth to an acoustic guitar recording.

IK Multimedia’s T-RackS EQP-1A is another great buy from a company coming on leaps and bounds in the vintage emulation sphere. It costs just €79.99 and adds M/S processing, although it doesn’t include the mid-range EQ. Meanwhile, Apogee’s EQP-1A is the only plugin available that’s endorsed by Pulse Techniques, but you do pay $199 for that extra seal of approval.

Those are just four of the bigger-named software emulations out there – there are even more from the likes of Softube, Acustica Audio, Melda and Overloud. You should also check your DAW’s EQ collection, as there’s every chance its vintage EQ might take design cues from the Pultec, with Logic’s Vintage Tube EQ being the most obvious example.

Of the freeware options out there, Ignite Amps’ PTEq-X is among the best, offering emulations of the EQP-1A, MEQ-5 and HL3C filter (often used to reduce low-end rumble and high-end hiss). Finally, Analogue Obsession’s RareSE bundle will also give you as much Pultec EQ power as you need for no outlay whatsoever.

Other modern Pultecs

Alongside the re-introduced Pultec EQP-1A from the newer Pulse Techniques, there are just as many hardware clones as there are software versions, but obviously, you will pay a lot more for any hardware Pultec emulation. Perhaps the best mid-range unit is Warm Audio’s EQP-WA, which does a great job of emulating the hardware for around £600. Tube-Tech’s PE-1C is also a well-regarded hardware version but does cost £2,500. The cheapest of all the clones is the Klark Teknik EQP-KT, which claims to offer all the original’s tube character for an incredible £299.

With so many software versions around – and free ones at that – we’d certainly recommend that route

Again, there are many more hardware clones available, often from smaller boutique manufacturers, but with so many software versions around – and free ones at that – we’d certainly recommend that route as your first intro to the Pultec sound if you are a newbie.

Should you opt for it, we have just the tutorial to get you going, and it’s based on the now iconic Pultec low-end trick.

How to use the Pultec EQP-1A

We’d honestly recommend trying an EQP-1A plugin – from any of the companies we mention in the main text – on your master bus just to add some subtle (or indeed, not so subtle) mix EQ to your tracks. We found that only using the Boost dials for the two bands is better here, and you could even consider using two EQs, with the second one’s lower or upper bands set at the furthest frequency bands away from the first.

We had one EQ set at 30 Hz for some gentle bass boost, for example, and then a second set at 100 Hz and it almost felt like a mid push, but experiment with any combination – the width of processing is so smooth that there’s little you can do to make it sound bad.

How to use the Pultec 'low-end trick' to improve your bass and kick

You should also give some thought to using the plugin with its EQ in bypass mode just to impart some of that (emulated) tube warmth – remember that, as with using a lot of vintage gear, just running a signal through its circuits can imbue some lovely character.

However, the best use of a Pultec EQ comes with the classic low-end trick, and that’s what we’re going to demonstrate here using UAD’s EQP-1A. Essentially this is boosting and cutting at the same frequency, but rather than one cancelling the other out, you get a resulting curve with more boost than cut and a notch which adds tightness and character to low-end sounds.

The Pultec low-end trick

The Pultec's manual says you should never use the EQP-1A’s boost and cut at the same time. We disagree...

Select a low-end sound so you can clearly hear the results. We’ll try the same ‘trick’ with the high-end frequencies later, but this technique is really better demonstrated with LF sounds. We’re using a Fabfilter Twin 3 for our bass sound.

Now pull the controls back to zero for Boost and Attenuation and select 60 Hz as your bass frequency, as this is the most common one used with this technique. Keep the Bandwidth dial/Q to a fairly sharp 3 at the moment, although the Q is never that keen with the EQP-1 – it’s not exactly known for ultra-precise EQ-ing.

Push the Boost dial up to around 7. Obviously, you’ll hear your bass get more pronounced and possibly even start distorting – don’t worry about this for now, as it should help emphasise the effect shortly.

Now push the Attenuation dial up. This is where the effect kicks in, but rather than canceling the boost out, the EQP-1 still applies LF gain, but with a notch before the HF gain. The result is a more rounded sound and any distortion should be reduced. Experiment to find the right position; if it sounds good, it is! Try setting Attenuation at around 4.

While you’re here you should also experiment with the Bandwidth; we did get a more pronounced bass sound by reducing ours (making it narrower), although to be honest, it was quite a subtle change.

Better still, try boosting the higher frequencies but at a lower band setting of 3 or 4. This certainly helps bring out the bass sound more, but be careful not to overdo it. You could even try the same trick again by attenuating the same band. It doesn’t sound as dramatic as the low end, but we’ve already achieved the result we need, so this would have just been a bonus had it worked well.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

“The included sample content is not only unique but sonically amazing, as it always was”: Spitfire Audio BBC Radiophonic Workshop review

“We were able to fire up a bass sound that was indistinguishable from the flavour of New Order’s Blue Monday in seconds”: EastWest Sounds Iconic review