“Ain’t nobody gonna believe I’d do this”: What Prince said to his engineer when he “unproduced” When Doves Cry and removed the bassline

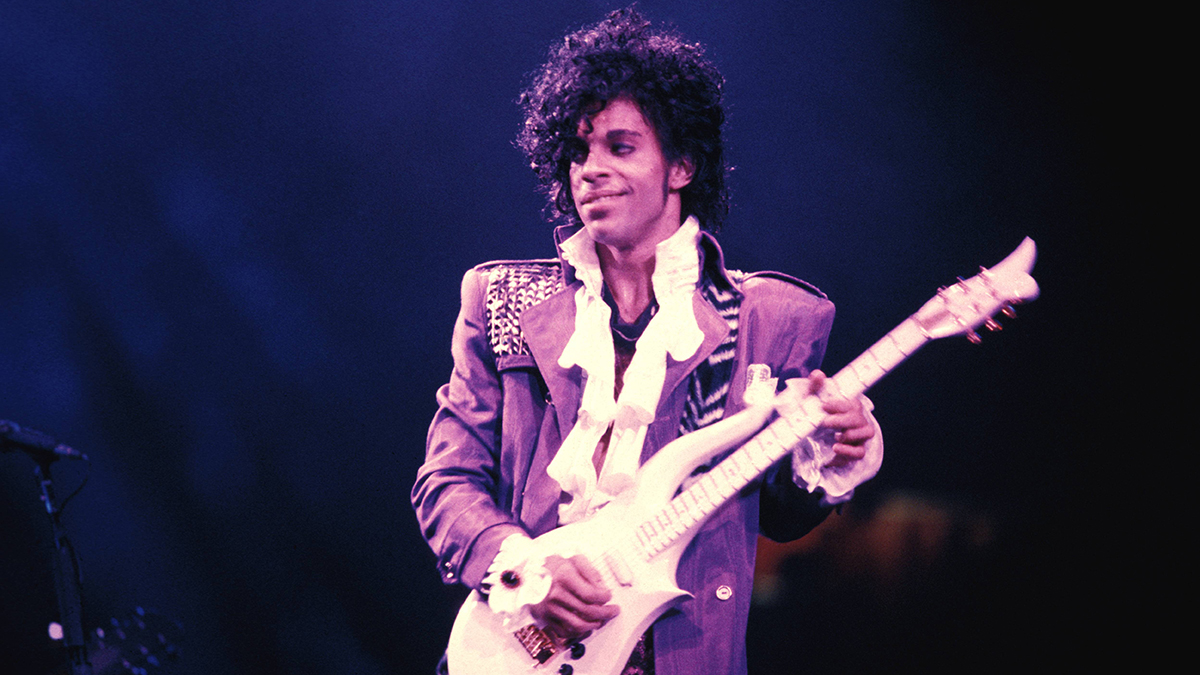

We celebrate the pioneering genius of the man from Minneapolis

In our Pioneers series, we unpack the genius of the most pioneering artists and producers in musical history. Here, we consider the career of someone who was both of these things and plenty more besides: Prince.

“I remember kind of shutting down on that song because it just seemed like a ‘wank,” Prince’s engineer Peggy ‘Mac’ McCreary told Sunset Sound Recorders. “Just like, ‘oh my god, here we go’ - the raging guitar and the raging synths and everything. It seemed so overproduced to me.”

McCreary is discussing When Doves Cry, now celebrated as one of Prince’s greatest singles, but it might not have ended up that way. She was in the studio when it was being recorded, but admits that, as the number of parts grew and the arrangement became fuller, she “kind of shut down”.

Cut to the last night of mixing, though, and Prince had a change of heart.

“As the night went on, things started coming out… he kind of ‘unproduced it’, if you can possibly do that. And then the last thing he did was he punched that bass out and he smiled at me and he said ‘ain’t nobody gonna believe I’d do this’. And he did.”

So, When Doves Cry ended up being released with no bass part. You might get away with that kind of tomfoolery now, but it must have seemed like a bonkers decision back in 1984.

It worked, though, and perhaps no story better sums up Prince’s attitude to arrangement and production than this one. While the ‘if it sounds right, it is right’ maxim can often come across as trite, in his case - and for better or worse - it seems to have been hardwired.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

While the ‘if it sounds right, it is right’ maxim can often come across as trite, in Prince's case - and for better or worse - it seems to have been hardwired.

See also The Ballad Of Dorothy Parker, from 1987’s seminal Sign o’ the Times, a song that has some very obvious sonic deficiencies. Prior to its recording, in 1986, Prince had been having a custom mixing console fitted at his new home studio in Chanhassen, Minnesota. However, he was so eager to get down to work that he started using it before the build had actually been completed.

Having been ordered to get the tape running, engineer Susan Rogers watched as the recording of The Ballad Of Dorothy Parker began, but she quickly realised that something was wrong.

“As soon as I heard it, I realised, ‘Oh my God, there is no high end,’” Rogers told the Red Bull Music Academy. “It sounded like there were low-pass filters on everything. First, I was thinking it was just one track. It wasn’t. It was the whole console.”

Unaware of the problem, and as was his wont, Prince just kept on recording. “It was like a baby eating baby food,” says Rogers. “It’s like, when’s it going to stop? He just kept going, and going, and going.”

She needn’t have worried, though. “I kept thinking, ‘Isn’t he noticing that there’s something weird with this?,” says Rogers. “We finally mixed the song. It was like a day later, and then he gets up and he’s all happy, because he got the song. Then he goes, ‘That was great. Good’. And then he goes, ‘This console’s nice. It’s kind of dull, isn’t it?’”

‘Wrong’ but right again, but it would be grossly unfair to say that Prince’s production career was little more than a series of happy accidents. Consider his mastery of the Linn LM-1, for example - has any artist ever been more synonymous with one particular drum machine?

"[Prince] didn't just select a stock beat and press play, but rather used [the LM-1] in unusual and creative ways,” the LM-1’s creator Roger Linn told Reverb in 2017. “From his detuning the drums to no longer sound like drums, to the unusual beats he programmed, to how he featured it in the mix."

And then there were the synths - specifically, the Oberheim OB series models that were all over his records in the early years. Speaking to MusicRadar in 2019, former bandmate Lisa Coleman (The Revolution) said: “Prince was incredibly bold in the way he would just use a preset and then brighten the fuck out of it! He would turn the filter way up so the sound would cut through the mix.”

You could argue that Prince’s astonishing levels of self-belief had their downsides - in later years, he could probably have benefitted from the ear of a trusted co-producer - but equally, one of his greatest achievements was to only ever sound like himself. And if you take only one thing from his remarkable career, let it be that.

Four tracks that demonstrate Prince's pioneering genius

Controversy - 1981

Its predecessor, Dirty Mind, is arguably the better album, but the title track from Prince’s 1981 long player provides the perfect illustration of what he was about back then. Funky, filthy and - according to some - blasphemous (he recites the Lord’s Prayer halfway through, as you do) it’s seven minutes of pure punk-funk pleasure.

When Doves Cry - 1984

Most famous for its ‘missing’ bassline, its removal leaves space for Prince to show off his LM-1 programming chops and deliver a lusty, sometimes anguished vocal. It also demonstrates his knack for coming up with simple yet hooky synth riffs - this one played using the Koto patch on the Yamaha DX7 - and there’s also a complex synth solo at the end.

In fact, Prince is said to have recorded this at half speed to make it easier for himself; Matt 'Dr' Fink, keyboard player with The Revolution (Prince’s band at the time), then had to learn it at full speed for the live performances.

Kiss - 1986

Originally intended for Prince protege band Mazarati, whose version was being produced by David Z, the great man ultimately released it as a single himself. Speaking to Sound on Sound, Z says that Prince heard what he’d done with it - including recording an acoustic guitar part and gating that to the hi-hat trigger - and said, 'It's too good for you guys. I'm taking it back.’” Throw in a trademark falsetto vocal and - boom - you have another huge hit.

Sign o’ the Times - 1987

Another example of Prince’s less-is-more approach to production, the title track to his 1987 double album - often considered to be his best - is bleak yet beautiful. The lyrics are perhaps the most overtly political of his career, covering all manner of then contemporary issues and crises, and are set against sparse arrangement that’s littered with Fairlight CMI presets. It still grooves hard, though, thanks in no small part to the choppy in-and-out guitar lines.

I’m the Deputy Editor of MusicRadar, having worked on the site since its launch in 2007. I previously spent eight years working on our sister magazine, Computer Music. I’ve been playing the piano, gigging in bands and failing to finish tracks at home for more than 30 years, 24 of which I’ve also spent writing about music and the ever-changing technology used to make it.