How to unlock the power of digital synthesis: "We are now at a brilliant point in synth history where analogue and digital are not only living side by side, but joining forces"

Hardware digital synths are back! Four decades after they became popular, renewed interest has led to new machines from both bespoke and bigger developers

Over recent years there’s been a flurry of activity from synth developers, both big and small, in the realm of hardware digital synthesis. Part of this is due to an increase in processor power, meaning that all sorts of digital synthesis techniques can be explored or re-evaluated, and all relatively inexpensively.

Eurorack has also been a big factor in the return of digital, as it was when analogue synthesis revived. The modular community has proved that there is an appetite for digital experimentation and this enthusiasm has spread so much that newer synth companies have started building hardware synths, including Modal (with the Cobalt, Argon8 and Skulpt), ASM (with its Hydrasynth), UDO (with the hybrid Super 6), Sonicware (Liven), Elektron (Digitone) and Teenage Engineering (OP and PO ranges). Unrestrained by previous labels and pigeonholes, these companies have released fantastic analogue, digital and hybrid synths with almost reckless abandon.

Synth companies have also learnt a lesson or two from the first generation of digital synths. As good as the Roland D-50, Korg M1 and Yamaha DX7 were back in the ’80s, the full extent of their capabilities often went unexplored outside of their presets. A famously huge percentage of DX7 users saw it as too difficult to programme and never bothered, and the menu-diving and lack of controls for many of those digital synths proved a real hindrance for musicians.

But now hardware developers have changed tack and are adding real-time, analogue-style controls to digital hardware synth engines. The new breed come laden with controls so you can shape their sounds and really get into their sonic guts, with an ease unheard of 40 years ago.

And the final reason that digital synths are making a comeback is that, as easily as they can be recreated in software, companies haven’t been afraid to run hardware digital synths with their software counterparts. Arturia’s MiniFreak, for example, comes with a software plugin – run the two together and you have the perfect marriage of control and convenience.

Arturia MiniFreak

We are now at a brilliant point in synth history, then, where analogue and digital are not only living side by side, but interacting, joining forces, combining and creating. Now is truly an amazing time to be exploring and shaping sound.

Arturia MiniFreak is a hybrid synth with a couple of multimode digital oscillators and an analogue filter and VCA, and very much the older sibling of the synth that helped reboot this digital generation, the MicroFreak. The core of its exceptional range of sounds lies in the number of modes the oscillators deliver – some 22 in total – the hands-on controls to shape them, and a fantastic modulation matrix to take the sounds on brilliantly dynamic journeys.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

On a basic level, you choose your engine for each oscillator. The six controls to the right of the oscillator selection button control various parameters including tuning, the engine type and mix volume between the two.

We are now at a brilliant point in synth history, then, where analogue and digital are not only living side by side, but interacting

The three remaining knobs – Wave, Timbre, and Shape – control varying parameters depending on the engine chosen. So they might control the wave type, detune amount and level of the detune waves in Superwave mode (very much the mode for massive trance supersaws); or they control the ratio of the operators, the amount of FM modulation and the feedback of the FM circuit within the 2-operator FM mode.

As you can see, then, we’ve already got access to big virtual analogue and digital-style parameters with just these three knobs, something that would have been completely lacking on ’80s synths like the FM DX7. And we’ve only touched on two of MiniFreak’s engines, at that! There are also modes for physical modelling, wavetable, multimode filter, speech and lots of other more quirky, modular-style modes.

You can go a lot deeper than this – and very quickly – by way of the modulation matrix, which we’ll explore below. This is key to a new generation synth like MiniFreak as it is so easy to initiate compared to older first gen digital synths, as many of the source and destination controls are to hand without any menu diving required.

The mod sources are a cycling envelope, ADSR envelope, two LFOs with custom waveshapes, assignable mod-wheel and keyboard velocity and aftertouch, plus two assignable macro sliders. These are listed top-to-bottom on the matrix, with the keyboard and macro option selectable beneath this. Destinations are set for the first four (Pitch, Wave, Timbre, Cutoff), but there are three assignable slots too.

MiniFreak modulation: easy and deep

Choose an initialised preset so you can really hear what we’re going to do as we modulate. Now select Waveshaper as our engine for oscillator 1.

We’ll start easy. Use the Matrix dial to move left/right (or Shift>Matrix to go up/down) and move to the LFO1 (source) and Wave (destination) slot. Now you can hear LFO1 change the Wave shape through saw, square, triangle and sine.

Modulating these four set destinations with whatever you like is fundamental to shaping the many digital engines in MiniFreak. But it’s just the start. Press and hold an Assign button and you can then select any other rotary on MiniFreak as a destination. We’ve chosen the Volume option for a pumping effect.

You can go even deeper with your modulation with these Assign options by holding one down and then turning the main Preset dial. This reveals an extended list of destinations including VCA and Vibrato amplitude and depth.

Frequency modulation in focus

Frequency modulation (FM) synthesis was the first big digital synthesis technique that was used back in the late ’70s and early ’80s.

At the core of frequency modulation is its use of operators which, on a basic level at least, you can think of as equivalent to oscillators. Operators can be either ‘carriers’ which feed their signal directly to an amplifier, so can be heard, or ‘modulators’; which modulate the frequency of the carriers in different ways, but can’t be heard individually.

Algorithms are simply different ways of combining carriers and modulators. The DX7, for example, had six operators and 32 such algorithms. The trouble with that was that most users of the machine appreciated it for its great (at the time) presets and weren’t that interested in getting involved with algorithms, operators and modulators, especially with a pretty horrible button interface, tiny screen and menus aplenty.

Many companies have updated the FM concept to try and make it more user friendly. Yamaha did a great job with the Reface DX keyboard, while Korg’s Volca FM is a beautifully realised, compact version. But the best in terms of use, power and flexibility is probably Korg’s Opsix, another six-operator FM synth, that integrates 40 algorithms.

As we state above, the new generation of digital synths work so well because of their real-time controls and Opsix demonstrates this really well, with six sliders increasing the level of each operator, and dials above them altering the ratio, another important FM parameter.

This is the ratio of the operator frequency, compared to the fundamental frequency of the note being played (so a ratio of 2 is double the frequency, or one octave above the fundamental).

Harmonic ratios (or integers) deliver pleasing melodic sounds – basses, pianos and so on – while inharmonic ratios can deliver wilder sounds and classic metallic FM sounds. Add in amplitude and pitch envelopes for each operator and you can create some incredibly varied sounds with FM.

The Opsix even goes further by adding other ways that operators can modulate carriers, including ring modulation and filter FM. This tutorial shows how easy FM synthesis is to use with Opsix.

Easy FM with Korg Opsix

Select an empty Init preset and you will simply hear a basic sine wave. You can dial through the 40 different algorithms by pressing the Algo button and moving the first Data dial. Just loading a preset and dialling through each of the 40 indicates how each algorithm can affect a sound.

As you dial in different algorithms, the colours change on the main sliders and Ratio dials. Here Algorithm 22 has four carriers in red on operators 1, 3, 4 and 5 which you can see at the bottom of the algorithm structure (on screen), and two modulators in blue at the top of the screen.

The Opsix has one other trick up its sleeve that FM never had and that’s the capacity to change the modulation mode. Hit the Mode button and dial the first data dial again to step through four other modes aside from FM, namely Ring Mod, Wave Folder, Filter FM and Filter.

A brief history of digital synthesis

The story of the digital synth is a little hazy, as a lot of research was being done in digital synthesis and computer music as far back as the 1950s. However, authorship of the first digital synthesisers available for the general public to buy – if for a hefty price – can be claimed by both the New England Digital Synclavier and Fairlight CMI (Computer Musical Instrument).

These would technically make more impact with their sampling capabilities in the ’80s – indeed the makers of the Fairlight coined the phrase ‘sampling’ – but the Synclavier also licensed FM synthesis from Yamaha for processing, and the Fairlight had enough sample editing to justify the name ‘synthesiser’.

Yamaha’s first synth to employ FM was the GS-1 in 1980, which at $16,000 was out of reach for most. At the other end of the scale, authorship of the first commercially available digital synth is also claimed by Casio with the diminutive VL-1 or VL-Tone that came out a year earlier. This £39.95/$69.99 keyboard was based on 10 square waveform variations with envelope editing – so technically a synth – but more toy-like in appearance and target market. It did big numbers though, around 100,000 sales a month at one time.

Yamaha’s FM-based DX7 can claim to be the first digital synth to make an impact in the music world, though. This 1983 keyboard would shift big numbers too – between 150,000 and 200,000 units – so was the first to threaten the domination of the then-popular analogue synths. That said, its actual synthesis was too complicated for most of its users to employ. They’d mostly simply enjoy the great emulations of bells and pianos and other more ethereal presets, rather than actually program the thing – that would be left up to the likes of Brian Eno.

Digital synthesis research was being done as far back as the 1950s

Roland eventually countered with the D-50 in 1987 which used a combination of sample and digital synthesis for its Linear Arithmetic synthesis and sold similar numbers to the DX7. A year later Korg jumped on the digital bandwagon, completing the holy trinity of famous ’80s digital synths with the M1, another sample-based digital synth that employed AI synthesis. No, not that ‘AI’: this stood for Advanced Integrated synthesis where digital oscillators were assigned sampled waveforms and a Variable Digital Filter and amplifier would help shape the sound.

There were many other digital synths in the 1990s, but the broad story is that people then got a little fed up with the lack of real-time control over many forms of digital synthesis and the menu diving that went with it, so analogue synthesis made a comeback. This was helped, somewhat ironically, by the boom in digital modelling which would give rise to virtual analogue machines and proved that people loved that analogue sound and feel, and the hands-on controls that went with it.

For much of the 21st century, then, and helped by the boom in Eurorack modular synthesis, analogue synthesis enjoyed something of a renaissance, but in recent years, digital has made a comeback. And here we are in the ‘best of all worlds’ present.

Andy has been writing about music production and technology for 30 years having started out on Music Technology magazine back in 1992. He has edited the magazines Future Music, Keyboard Review, MusicTech and Computer Music, which he helped launch back in 1998. He owns way too many synthesizers.

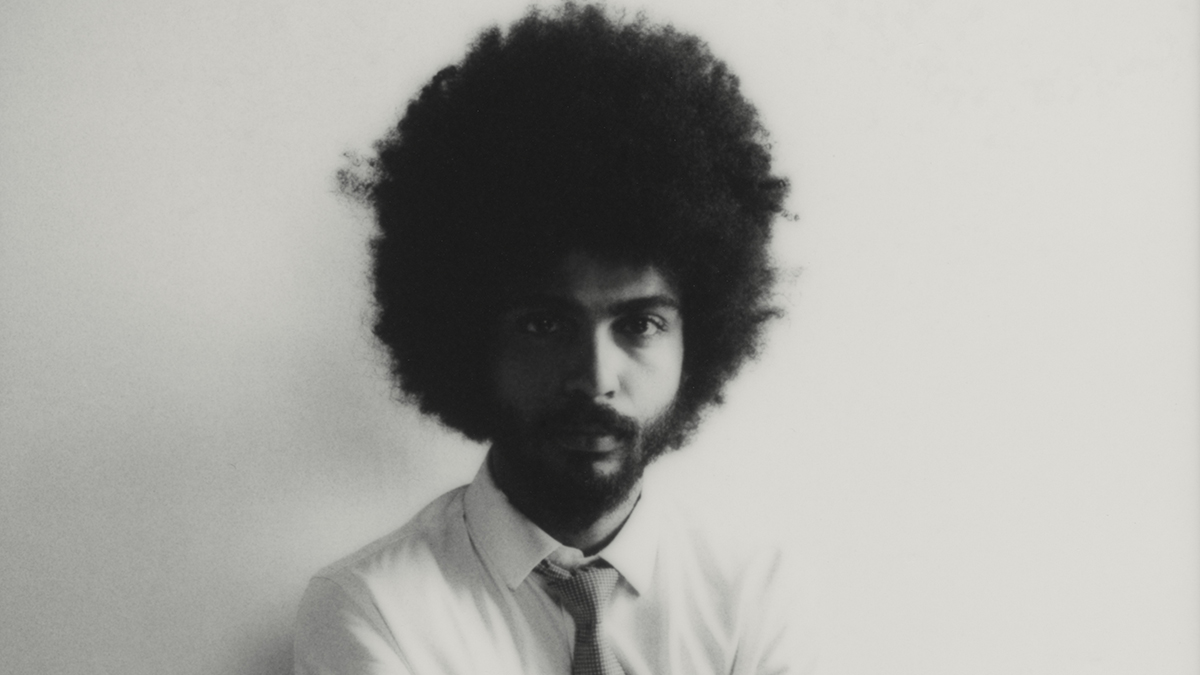

“I just treated it like I treat my 4-track… It sounds exactly like what I was used to getting with tape”: How Yves Jarvis recorded his whole album in Audacity, the free and open-source audio editor

Waves makes 7 plugins available for free, including convolution reverb, FM synth and tube saturator

![Gretsch Limited Edition Paisley Penguin [left] and Honey Dipper Resonator: the Penguin dresses the famous singlecut in gold sparkle with a Paisley Pattern graphic, while the 99 per cent aluminium Honey Dipper makes a welcome return to the lineup.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/BgZycMYFMAgTErT4DdsgbG.jpg)