Pop super-producer Rami Yacoub: "Max Martin said 'this is the magic'... It was pretty amazing”

Britney, NSync, Backstreet Boys, One Direction… Meet the man who's worked with them all

Ever perfecting, ever evolving and always ready for the next step, Swedish producer and songwriter Rami Yacoub has been the driving force behind a cavalcade of hits that are too long to list. If we were to try, though, we could mention Britney, NSync, Backstreet Boys… Niki Minaj, One Direction, Demi Levato… Lady Gaga, Ariana Grade and more.

From working with Max Martin, pioneering the collaborative writing and production style that’s become the norm, and pushing boundaries both musical and technical, Yacoub has seen and done it all.

Time for a chat, then...

Where is your main studio these days?

“I’m based in LA. The studio is in West Hollywood. Not too far from home. It’s Max Martin’s studio; it’s been about seven years since he built the place

“Max and I worked together from ‘97. For about seven years. Then I took five years off as I was really tired. I know, it’s a long pause. We were so close, but after seven years we became like an old couple. I was supposed to take one year off, but it became five.

“Those five years just went by and then getting back into it I started working with Carl Falk and we did all the Niki Minaj and all the One Direction stuff. I did that for about five years and then I took time off with my wife and to look after my son. But then I felt I wanted to come back to the family and Max is like ‘the door is always open’. We have a great group of people - 95% of whom are Swedish so it feels like home!”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Things must have changed a lot over the years.

“When I started out in ‘94, ‘95, it was very expensive to even attempt to do music. Equipment was insane, you needed Pro Tools interfaces, and we used to record on analogue tape.

“Then we switched to recording vocals into an Akai sampler and we had a Euphonix CS 2000 board, which we loved, and we had a lot of outboard gear. Plugins didn’t exist so we used a lot of hardware synths - the Roland JV-1080 and JV-2080. We had about four or five of them in a stack.

“The 2080 was the main synth at Cheiron [Studios - home to the early hits] .We had all the expansion cards and that’s mainly what we used for all the stabs and the pads.

“At that time it was revolutionary. Every time they released a new expansion card we just ran after it! That was the main synth and then the Euphonix desk meant that we had our own sound.

“People ask ‘how did you create that sound’, but it’s not like you ever put yourself in a situation where you say ‘I’m going to create a new sound’. It doesn’t work that way. You get your sound by NOT having access to sounds!

“It’s not like today where you have things like Splice and there’s a whole ocean of sounds that are amazing. In those days we bought sample CDs, mostly from Germany. Or if we wanted a ‘snap’ we had to do it ourselves. We had about 100 sounds! Ten hi-hats, ten snares, ten kicks and we just kept using and tweaking those. And that was the sound.

“We worked in Logic and Logic at that time was amazing compared to Pro Tools. The workflow just kept going… We had the kick and the drums… We used the same hi-hat, we used the same stabs, the same swooshes, the same pads ‘cos we were focused on the song and we built everything else around it.”

“Our hard drive became our holy grail - our vault. We didn’t give out our sounds. We even kept quiet about what synths we used. People would go to our local music store - travel from around the world to go to this Swedish music store - just to ask what synths we were buying! And the guys in the store would say some synth that doesn’t even exist! Just for fun.”

Is there one piece of gear from Cheiron that you miss?

“Probably the Euphonix desk. The CS 2000. There was just something with the processing. I remember clearly when I started working with Max [Martin] at Cheiron. I came in with my own sounds and stuff, but when we went to make a song he showed me how it works.

People would go to our local music store - travel from around the world to go to this Swedish music store - just to ask what synths we were buying! And the guys in the store would say some synth that doesn’t even exist! Just for fun.

“He said ‘this is the magic…’ and he routed the kick on one, snare on two, hi-hat on three, loop on four. And then he pulled up one lever at a time, and I was like ‘holy shit, this is the sound!’ It just had this analogue-digital compression to it which was hard to explain. It all made sense on that board. It was pretty amazing.”

Tell us about writing and production collaboration. You seem to enjoy working as part of a team rather than solo?

“Back in the day at Cheiron we were isolated. We had our own bubble. We didn’t bring in outside people. We had all we needed right there. Me, Max, Andreas Carlsson, Per [Magnusson] and David [Kreuger]… we were like seven, eight guys between two studios. Six producers and two writers. Me, Max and Kristian Lundin. And Per and David were in the other studio.

“The doors were always open, so when a project came in - which at that time was usually the main artists from Jive [Records], so Britney, Backstreet Boys, N-Sync - that’s all we had time to do before we’d start over on the second album, and third album…

“Nowadays you have like five or six writers. You can see up to 12 writers on some songs. In most cases - even when you have six, seven writers - they’re never there in the same room. There’ll be two or three people at the most. And then they want a new part and so it gets sent around and everyone takes a cut from the song. You have somebody that’s the producer of the song, and they’ll have a co-producer, and they’re going to take publishing, so they’re writers on the song too. Everyone takes a piece of the publishing so it’s started to become insane.

“I’ll do a song, and it’ll go around and somebody will reproduce it and all of a sudden there’s four extra writers added and one guy added a hi-hat. I’m serious. It’s becoming insane. And he gets 5%.”

What is it that you bring to the song?

“There are a lot of different types of writers. Some are great at concepts and lyrics. Some are really good with melody. I’m more of a structure, arranging guy… I don’t walk into a studio and start singing a million melodies. I kind of ‘process’ stuff. I need a moment. I need 35, 45 minutes before I spit it out to make sure that it’s great.

“I’ve worked with a lot of young writers and they’re like machine guns - they spit out a million things, but I’m really good at catching the stuff I think would be good. They do things and they think it’s done, but I’m like ‘no, it’s not good enough’. And that’s a mentality from the Cheiron days.

I’ll do a song, and it’ll go around and somebody will reproduce it and all of a sudden there’s four extra writers added and one guy added a hi-hat. I’m serious. It’s becoming insane. And he gets 5%.

“Y’know Denniz Pop was like our main mentor, our godfather. And he was like ‘if it’s not good enough, kill it’. The expression “kill your darlings” was the phrase he used. If it doesn’t feel good we’ll just start something new. I leave no stone unturned, I don’t leave anything to chance.”

Do you have a routine that you always follow?

“I never start writing to math. But I have it in the back pocket. If it doesn’t feel right I dig out the notebook in my head and I’m like ‘ok, are we using a lot of the same notes in the verse, the pre and the chorus? Are we using the same cadence? Are we doing the verse, pre and chorus on a pick-up?’”

And are you influenced by new sounds?

“Oh yeah. Sounds really can inspire amazing stuff. It’s not always that I have a chorus that I can sing acapella and then I go into the studio and play music to it. Sometimes it’s the opposite. I just downloaded Analog Brass and Wind for Kontakt 5 [by Output] and that has some amazing stuff and that’s just inspired me to write a whole new song.”

Tell us more about your writing process.

“I’ve been taking more of a passenger role on being a producer because I want to focus more on writing. So usually when I write now I have a great producer and a partner who sits on the keyboard and is the main machine for production. I keep it very simple with just a piano or a guitar and maybe just a kick or a loop. ‘Cos if it’s good enough like that, it’s going to be amazing when there’s a production. So, it’s not like it’s done and I say ‘OK, now I’m adding THAT’.

“To be honest, I’m always amazed - you start on a Monday and you walk in and for the first ten minutes it sounds like monkeys in a studio! It’s like he’s playing a kick, he’s playing a drum… There are people singing everywhere… And I’m like ‘how is this becoming a song?’ but I know that by Friday we’ll have an amazing song. It’s kind of mind boggling.

“Some artists come in with a very strong point of view for what they want to do, which I love and I prefer ‘cos that gives us some kind of direction as to where we should head. And some artists are a bit more lost and don’t really know which way to take it and they want to try out stuff. But the process is usually the same.

“When you walk into a room to write with an artist there can’t be any egos. Nothing is personal. If somebody doesn’t like my melody I’ll come back with ten more. In the end we all want what’s best for the song and the artist has got to love the song, so the final word is whatever he or she says. You can’t say ‘this is a hit melody and you’re going to sing this’. It doesn’t work that way. It’s their song. You’re working for them. You’re trying to make them happy.”

Have you ever had a session that hasn’t gone well?

“If it hasn’t gone well in terms of writing, ‘cos it’s slow, then you call it a day and take it up the next day. You can’t force anything.

“There was an instance where I was working in the studio with two other writers and the artist was very musical, he was more ‘indie’ and he was really vibing with this other writer, who was also an artist, but it was way off what could ever be a top 40 hit. I didn’t say anything for like three hours; they were so excited by what they were playing. So after three hours I said ‘Listen, whatever you guys are doing, it’s great, but I can’t contribute anything so I’m going to remove myself from this room’. But other than that, I’ve been pretty fortunate.”

What’s your gear setup looking like these days?

“Basically everyone has a laptop - a Macbook Pro - and people are working in Ableton [Live], Logic, Pro Tools, Cubase, whatever they prefer. And we have different rooms; nobody has a set room, so we kind of plug in to the system there.

“We use a [Universal Audio] Apollo interface or maybe a [UA] Arrow - that’s the outboard and the microphone is the only hardware we go to. The main mic we go to is a [Telefunken] ELA M 251 and we go through a Chandler TG2 [preamp] and a UA 1176 [limiter]. That’s our mic chain.

We use a Sony C800G once in a while and in the writing process we use a [Shure] SM7. That’s our go-to mic when we write, when we’re trying to figure out melodies, but we’ve also kept vocals from it. Big artists. Just recording in the room, without the booth. The SM7 has a grit to it. And if Micheal Jackson can record with it…”

Tell us about a fun session you had where everything clicked.

“There are so many songs, but I think when I worked on the One Direction stuff. When we did What Makes You Beautiful. We hit something - the sound and the style. And that was beautiful. It was guitar-based pop. I truly loved those moments because everything just came along so well. It became more sophisticated. They weren’t The Wanted. Or Backstreet Boys. It wasn’t meant to be like ‘super cool’. With the music and the guitars, it was just like a perfect fit.

“With What Makes You Beautiful we were stuck on the verses but we had the chorus. So we started another song and two days into that we couldn’t figure out the chorus. So we thought ‘what if we took the verses from one song with the chorus of the other?’ And that’s what happened. Taking bits and pieces and making it perfect.”

Just to go back to the start, Simon Cowell tells a story about hearing Baby One More Time at Arista records and thinking it was the best song that he’d ever heard. He wanted to get it for his boyband 5ive but it’d already been promised to Britney Spears? How do you remember the story?

“I know Simon Cowell has an amazing taste for songs, so I don’t doubt that that’s true. I know that 5ive came to the studio and they worked with Andreas Carlsson and Kristian Lundin who did Bye Bye Bye. And they recorded the song. But 5ive didn’t like it. Simon was trying to get songs for 5ive but they didn’t want it. And so it went to NSync.”

Tell us more about the ‘tricks’ you used to use when writing. You’ve created some amazing middle eights that would basically be a chorus but with a completely different vocal melody, then the original chorus would return, and then that middle eight melody would join it. Like on Oops I Did It Again...

“Yeah, we called it the B-chorus! The chorus would come back and then the B-chorus would play under the chorus in harmony. It’s a hard trick, but I did it with an artist just last week.

“You have to write another chorus that sounds amazing by itself. But then it has to fit perfectly under the other chorus, and you kind of have to use the same words but less busy. If the original chorus is staccato then the B-chorus has long notes; I’ve done it a couple of times in the last six months. I want to bring it back because it is kind of fun.”

And choruses where the music drops out. You get to the point where the chorus kicks in and it should be this big peak… but the music drops out? Like Starships or Pound The Alarm by Niki Minaj?

“Yeah, that’s an anti-chorus. It’s not something that you work out when you’re writing. If you and I were writing a song I’m not going to say ‘this is the verse and the pre and this is an anti-chorus…’ It happens when you have a vocal recorded and you start producing the song and something isn’t right when you get to the chorus. Then you try it. There’s just something when you drop out the drums and you have a bass and a pad and the melody… You feel it instantly if it should be an anti-chorus.”

You can’t give them too much of the good stuff, otherwise it wouldn’t be special.

And we wanted to ask about a certain chord change you use… A good example of that would be When You’re Looking Like That by Westlife? The chord change? Seven seconds before the end?

“I love that song! I know what you mean. It’s a diminished chord. It’s that little lift. You feel it in your belly. Like ‘oh, what just happened’? We put it in there just once at the end. You can’t give them too much of the good stuff, otherwise it wouldn’t be special.”

How has producing music during the pandemic been for you?

“I’ve been working with Ava Max, Charlie XCX, Normani and Lizzo. So I test myself every day. And it’s not like I go out clubbing. I go home to my family. So it’s been pretty hectic but from April we’re reforming our schedule to have sessions one week and one week off to look at what we did, because right now I don’t have time to even process what we did. I don’t have time to see which songs are diamonds and which need to be fixed. Now we have a week to fix what we have done, and a week to prepare for the week after.

“I try to book sessions with artists that aren’t just one day or two days. Even if they can only give you two days. I mean, it’s like a blind date - you don’t know each other. But if you do click, it feels like you’ve known them for years. I’m pretty good at putting people at ease.”

And the studio in LA helps with that?

“Yeah, we’re sitting in an amazing studio but it’s not built as a recording studio. I don’t like studios that are like ‘ghost’ studios. They suck. They’re boring. An SSL board… Tasteless. Not inspiring whatsoever.

“Max’s studio is an old house. It’s Frank Sinatra’s old house actually. If only you could see it, it’s beautiful. There are handmade carpets, beautiful sofas, a library, a fireplace, a deer head, a bar… It feels like you're stepping into Frank Sinatra’s art deco home.

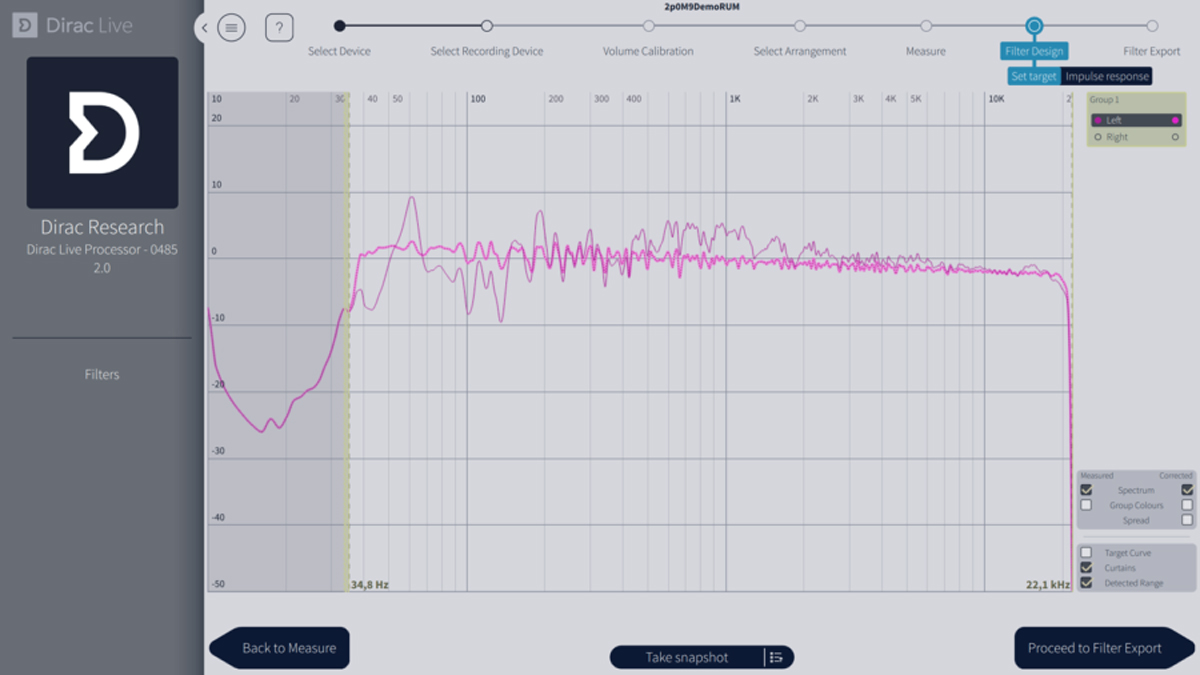

“He didn’t make it like a ‘spaced out’ studio so the sound is not really perfect. So I set up Dirac Live and I measured the room. You know when you sit in front of the speakers and you lean back, or you reach for your coffee and everything shifts? Dirac was like someone just popped this room into another room and made it soundproof. It was insane.”

Dirac Live almost sounds too good to be true...

“Yeah, it is. I got introduced to the company and went to their offices outside Stockholm and it just blew me away. It’s a correction solution, minimising the impact that a room has on the sound without requiring expensive treatment. So it’s like you sitting in a perfectly built room. It removes any colourisation and gives a true representation of what’s going down.

“You do a measurement with a mic and it takes about five minutes. You put the mic in different points - there’s a picture that shows where to put the mic - and then you save it and it becomes a plugin that you put on your master and you can turn it on and off.

“We have four rooms and I usually work in the pink room. In there we have [Yamaha] NS-10s and there are big Focals. So you do two different measurements and they’re just a click away - one for the NS-10s, one for the Focals. And when you move studios you just make a new save file.

“It’s night and day. I really hope it becomes a standard.”

That’s the hard part. Taking days and weeks but in the end it sounds like it took ten minutes.

What do you think is the best bit of advice you’ve ever had?

“To be critical. Not settled. Do not play it safe! Making every part as perfect as it can be because in the end it might sound like we wrote the song in ten minutes because it all sounds so fluid and great but it took three weeks. That’s the hard part. Taking days and weeks but in the end it sounds like it took ten minutes. Because you can hear if you’ve worked on a song for too long.

“These days I’m like the relic in the room. I’ve aged in well! So when they say ‘we have a week, let’s write six songs’ I’m like ‘no, if we have ONE undeniable chorus by Friday, I’m happy.’ All we need is one hit song.

“I want everybody to love the song. I don’t want 70% of people loving it and 30% not. You’re never going to grow if you think everything you do is perfect. Nobody stops learning.”

One last thing. You produced It’s Gonna Be Me for NSync. Can you settle this one for us? Why does Justin Timberlake sing ‘Me’ as ‘May’?

“When we do vocals we want to over-pronounce everything because we want everything to be super clear, right? So it wasn’t just the word ‘me’. If you listen to the song, in the chorus [sings] ‘I don’t wanna loooose it again’… We had him over pronounce ‘lose’… If you listen carefully… Like ‘my looonliness is killing me’… It’s all very over pronounced. So the ‘me’ thing became really hooky, and became really different… and annoying. But Clive Calder walks in, who was the head of Zomba [records] and very involved with all the projects, and he was like ‘I want more may!’ Justin was ‘you want more?’ It’s good to have some memes! Like ‘May’ and ‘Oops’. It’s kinda fun.”

Daniel Griffiths is a veteran journalist who has worked on some of the biggest entertainment, tech and home brands in the world. He's interviewed countless big names, and covered countless new releases in the fields of music, videogames, movies, tech, gadgets, home improvement, self build, interiors and garden design. He’s the ex-Editor of Future Music and ex-Group Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Musician, Guitarist, Guitar World, Computer Music and more. He renovates property and writes for MusicRadar.com.