Pole: "I’ve learned to appreciate mistakes - the weird, mosquito-sounding synth on this track was a result of my Minimoog dying"

Stefan Betke has continually blurred the contours of electronic and dub music. Danny Turner hears about his latest evolution

Stefan Betke is now into the 22nd year of an artistic career that began in the late ’90s with the era-defining Pole trilogy 1, 2 and 3.

Always seeking to expand his musical language, Betke’s idiosyncratic sound explores concepts of past, present and future within the pace, tone and echo of his favoured dub music aesthetic – a journey that’s continued to evolve across a further four albums: Pole, Steingarten, Wald and Fading.

Betke’s latest offering, Tempus, continues his explorative voyage by shifting his dub-inflected concept in the direction of jazz. Abstract and minimal yet warmly inviting, Tempus’ interpolating bass, innovative-sounding percussion and synths are immaculately constructed… little surprise to those familiar with Betke’s day job as a skilled mastering engineer operating from his Scape Mastering studio in Berlin.

You’ve mentioned that Tempus is a natural development from your last album Fading. Tell us more about that…

“I’ve been using the same technologies for the past 20 years, so my development of Pole is not really about the tools I use in the studio but my philosophies behind making music and how I use and refer to existing styles and genres like dub and jazz. I’m continually deconstructing and rebuilding elements from the musical language that I’ve been working with since the beginning of my Pole releases in the late ’90s.”

What methods do you use to convey the various concepts that you’re exploring through the music?

“About 30% of it is pre-planned – I have an idea of what I’d ideally like to do and then I go into the studio and try to work on the structural ideas and atmospheres that I have in my head to see what happens. With instrumental music you can’t put anything into words so everything has to come from the instruments that you’re playing. That goes hand in hand with accidents and elements that I try to develop, mute and destroy until, if I’m lucky, everything comes together.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

If you find that your creativity is taking you into an unplanned direction will you run with that?

“If it leads me into a totally different direction that has nothing to do with the original concept I’ll have to rethink the concept to make sure it’s still valid to work on or just restart. That happened once with an album that was never released because it ended up being so different. Ideally, I’ll keep one or two unfinished tracks and wait to see if they fit with something in the future or take samples or loops from them to use for one of my live shows. Otherwise, those ideas just sit in the box forever [laughs].”

The album cover is an oil painting – one of yours?

“It’s an oil painting on canvas made by my brother Wolfgang Betke. We always wanted to work together on the art for one of my music covers but it never really worked out. This time, we gave it another try, put about 15 paintings on the table and listened to my music until we found one that fit with the atmosphere of the album. I’m not saying it because he’s my brother, but he’s super-talented. He deconstructs references in art in the same way that I do with music and this time we found that the depth, power and complexity of his work referred well to the new album, Tempus.”

Throughout your career you have subtly shifted between genres, but dub music has always been ever-present…

“To keep a long story short, dub music – or the message of it, which is basslines and the depth and space that delays, reverbs and effects units can create – was always a big influence in my own work. I was never trying to make dub music, even though the trilogy that I released between 1998 and 2000 was so closely related to it.

“In the end, so many people referenced or saw me within that context that I had to be honest with myself and say that my relationship with dub was more than just about deconstructing it. I have moved away from that at times, but every album still has the same heavy basslines, rhythmical delays and loose reverbs.”

Dub music has a very laid-back ambience. Presumably, that low energy allows you the time and space to express yourself?

“It’s definitely helpful. The faster the music is, the more you have to focus on keeping it together in a funky way. At the same time, you can cover mistakes. A really interesting bass player that I worked with in the early ’80s told me that it’s really easy to play a shitty track fast and make it sound good but really complicated to play a shitty track slow and make it sound good. Dub music has the tempo for dance music but it’s still spacey and played in half-time, mostly.”

Percussion seems to be equally important to how you try to convey mood and emotion in your music?

“Percussion is one of the most important elements in my music in general. It doesn’t matter if we’re talking about the crackles on my first three albums, the drum programming on Tempus or how I use chords and delays because I play keyboards in a way that’s percussive rather than melodic. The idea is to create a rhythmical structure with chords, bass, little sound snippets and delays that combine to create melodies by themselves.

I’ve learned to recognise and appreciate mistakes and give them the chance to breathe

“For example, if you repeat a single note in a delay and put it into a room, it starts resonating and builds a melody on top of the basic chord. You never really hear a big tonal change because I’m not going from C major to A major, for example, but melodies seem to appear from the playing of all of those single elements together. Even a resonating snare sound can create a melody.”

Are your percussive sounds derived from physical instruments or software samples?

“Unfortunately, I can’t play the drums so I sample snares and hi-hats separately and play them on an Akai MPC2000. Next year I’m going to try and work with a real drummer, especially in live venues where it makes sense to do so. In music you have to take risks and I feel that the input musicians can bring when interpreting the parts that I’ve composed might open a door for me.”

Tempus is full of very intricately configured sounds. To your credit, it doesn’t sound mechanical… how?

“It never becomes mechanical for me because I’m playing every instrument and have to sit at the keyboard and learn how to play the ideas in my head. I’m also programming the beats myself so I have to learn how to reach a certain level. Every time I start a new track it’s a challenge, which keeps the creative process really diverse because different solutions are needed from track to track.

“At the same time, when you make conceptual music you have to think about certain technical formats to make sure that the mechanical process you speak of is running naturally in the background and doesn’t block your creative or musical headspace. You can’t really separate the two.”

We understand the track Stechmuck was an example of a mistake changing the trajectory of the track?

“I’m not looking for mistakes on purpose but since the first mistake I made led to my first trilogy of albums I’ve learned to recognise and appreciate mistakes and give them the chance to breathe. Sometimes that doesn’t happen for a long time but Stechmuck has the biggest mistake on this record because the weird, mosquito-sounding synth on top of the track was a result of my Minimoog dying.

“That sound was originally the bassline but the oscillator couldn’t get enough energy and stopped working, so I recognised the mistake and used another instrument for the bassline. When that sort of thing happens it’s really lucky – I was super happy for about a week [laughs].”

You mentioned jazz earlier and the piano refrains on the track Firmament seem to take you into new territory in that respect?

“It’s funny that you mentioned that because nobody else has so far. It’s the first time that I really tried to play piano again. I started on classical piano and stopped for a long time and only played synthesisers, which is obviously a totally different way of playing an instrument.

Once a sound is made, I’m not really interested in preserving it, I’ll just turn off the synth and the sound is gone

“With Firmament, I was playing a piano on top of a bassline and liked how they worked together. Then I slowly reduced the piano and replaced certain chords with synth sounds so the piano is responsible for the tonal aspect but supported by additional chords. Perhaps that’s why the track stands out as one of the most obvious jazz-influenced ones.”

Going back to the Minimoog, are you generally a proponent of using vintage synths?

“I’m a fan of anything that helps me to create the world I’d like to represent. I’m not an analogue purist – if a plugin helps me to create the sound I want I’ll use that, but I’ve been working on music since the early ’80s so I happen to own a Minimoog, a TR-808, Prophet-T8 and a Yamaha DX and I’m using them heavily.

“I also have a modern Eurorack modular system and a Buchla Easel. The good part of having so many different analogue synths is that you can capture an idea quickly because you don’t have to programme or patch anything.

“Then it’s often a case of what will the modular system say if I play the same notes with different patches, so I’ll switch the same chords, basslines or rhythmical structures to different tone generators and use oscillators to modify those instruments so they don’t sound like themselves, or maybe I’ll just record stuff and fuck it up in the computer using granular synthesis. I really appreciate having that element of flexibility.”

Did you get into modular very early or was Eurorack the entry point?

“The first modular system I had was a Roland M-1000 in 1984. I never had the money for an EMS system – they were really expensive in the ’80s, but I had a Korg MS-20 semi-modular and then in the mid-’90s the Doepfer Eurorack system appeared. I’ve bought and sold systems and now I have a modular one in combination with the Buchla Easel.”

Does modular require a different creative approach in your opinion?

“You can’t compare it with any other synthesiser that’s pre-patched because you need time to make a proper patch work in your system. If you only work with modular it can be a relatively fast process because the rhythmical stuff and timing is generated within the same system, but when you combine modular with external rhythm machines, synths or a computer, you have to find a way to patch it and that makes everything a little more time-consuming.”

Do you generate sounds in the box too?

“I might use Ableton’s Operator like a synthesiser tool and create something from scratch but I’m not into saving music as presets and reproducing them for the next album. Once a sound is made, I’m not really interested in preserving it, I’ll just turn off the software or hardware synth and the sound is gone. For my own recordings, I mainly use Pro Tools or Ableton and I have Logic too but it’s not something I use that much in my own production world. Basically, I find it convenient to do MIDI recording in Ableton and audio recording in Pro Tools.”

Tell us about the other side to your career, which is as a mastering engineer. What was your route into that?

“I became a mastering engineer because I needed money when I moved to Berlin. I already had some knowledge of EQs and compressors from working in recording studios in Düsseldorf and Cologne, but I met some Dubplates and Mastering people and got introduced to the process of cutting vinyl.

“After working for them I figured out that working as a mastering engineer opened up a lot of doors in my head – I suddenly understood the other side of production and had the space to make my own compositions because I was able to pay my rent as a mastering engineer. Now I’m able to listen to other artists’ music from a different perspective because I’m not just a technician but a musician.”

Does having a studious approach to music in your professional life make it difficult to listen to music objectively in your free time?

“Being a mastering engineer I’m obviously used to listening super precisely and deeply into every element of a track and can never really get rid of that when composing my own music. Even in a club I’m counting the beat and examining every little part, which I know is stupid. I do really enjoy listening to other people’s music, but sometimes I’m thinking more about how it’s made than what it does to me. Sometimes I have to sit down and remind myself that I’m not mastering a track I’m just enjoying it.”

Will you master your own music?

“Not anymore – I tried it once but it took five months. For both Fading and Tempus I used Barry Grint from Alchemy Mastering in London and I’m super happy with what Barry did because he had a perfect understanding of the music and made it sound amazing. For me, the reason an artist hands their music over to another person to master is split into two parts.

It’s frustrating that artists and labels put so much money into a good mix down or master, only for someone to play it back on a cell phone

“One is the technical side, which is no big deal because it’s something I can do myself, but the main thing is that you need a fresh pair of ears and somebody who can objectively tell you whether a snare is too loud or if something doesn’t sound clean. When I mastered my own music I found so many elements that I could have done differently in the mix, for example, I’d go back in and put the bass up 1dB and return to the master, but now the kick drum wasn’t loud enough so I’d have to go back into the mix again.

“That doesn’t help anybody. The artist should do the composition, the mix engineer should do the mixing – although nowadays they are usually the same person – and then you need a third person who listens and says, okay, I understand your idea and I’ll help you to make it sound good on every system.”

What’s your view on how the mastering engineer’s role has evolved over the past several decades?

“At the beginning of the ’80s when the CD came out, not that many people mastered for it – it was mostly printed to a glass master and reproduced to CD in a factory. Before that, you just needed someone who could transfer a recording of, say, The Beatles, from the mixing room onto a vinyl cutting lathe that was standing in the cellar of the same building. They sent down the tape and the technician transferred it and then shipped it to the pressing plant.

“In those days, there were not many ideas about how to optimise sound but we’re now living in a world of MS encoding and have tons of tools to change a general recording or fix mistakes to make the vocals less harsh or the bass less loud. A bad song is a bad song and the mastering cannot help that but it can help with the tonal listening quality. Obviously it’s frustrating that artists and labels put so much money into a good mix down or master, only for someone to play it back on a cell phone.”

Is there any conceivable benefit to that?

“I suppose that if somebody is really interested in music they might start with a cell phone or by listening on Spotify, just like I listened on a mono radio system before recording to a cheap cassette player.

“Every record that I thought was interesting to me I bought later on vinyl, so you can start with a shitty system and if you’re really interested in fidelity you will change the listening quality at a certain point. It’s a bit like how people going to a gallery and looking at a Van Gogh original that looks exactly like the print I have in my kitchen.”

You run Scape Mastering in Berlin. Do you master for a specific area of music?

“I’m able to work with a big diversity of artists, so I’ll master for Alessandro Cortini in the same way that I would for Martin Gore or techno, listening jazz, dub reggae or dubstep producers. As long as you’re respectful as a mastering engineer and don’t pretend to have knowledge of a genre, then you can help them.

“I like to think I have a lot of knowledge because I’ve been listening to lots of different music for a long time, but I’m very thankful to be able to work with so many interesting artists and hope they can continue to trust in me and we can continue supporting each other.”

You have some Studer tape machines. Under what circumstances will you use those on productions?

“On my own productions, if it makes sense musically, I’ll run stuff through a Studer A80 ½-inch tape recorder to record the stereo file before I send it to mastering. When it comes to mastering for others it’s the same; if I think a track needs an analogue upfreshing because it’s primarily been made in the digital domain, I’ll run it through some analogue EQs, into the tape machine and then back into the digital world.

“I also have clients come with old recordings on tape that need to be played back for remastering. I did Alphaville’s whole back catalogue two years ago where all the original recordings were on tape, so I’m lucky to have these machines to play them back on and all the equipment here is in perfect condition.”

You have some very pricey gear. What would you recommend people on a budget use instead?

“Nowadays, the algorithm in computers and plugins are so good that, without wanting to advertise these companies, you can use nearly any Softube, Plugin Alliance or UAD Audio plugin on your tracks. For example, I have both the plugin and hardware version of the Dangerous Bax EQ and although the plugin is not the same it’s very close. That stuff is affordable but if you want to go one step higher you can always buy used equipment – a Klark Teknik DN410 parametric EQ can be found for reasonable money and you can always get it refurbished if you’re willing to pay another £150.

“If you have a lot of money you can end up buying a Manley Massive Passive EQ for 7,000, but I’d recommend every producer follow the technical needs that they have. Invest first in the room sound so that you’re not sitting in the wrong position. And then a good speaker system, because a good EQ won’t help you if you don’t have a good speaker to show what you’re doing with it.”

What speakers are you using for monitoring?

“In my main studio I use ATC 110s and in the smaller room, which is only 15-20 square metres, a pair of Neumann KH 310s with a subwoofer system. If I was only running one room I’d go for two speakers for referencing, but luckily I can transfer the audio between the two rooms via Ethernet.”

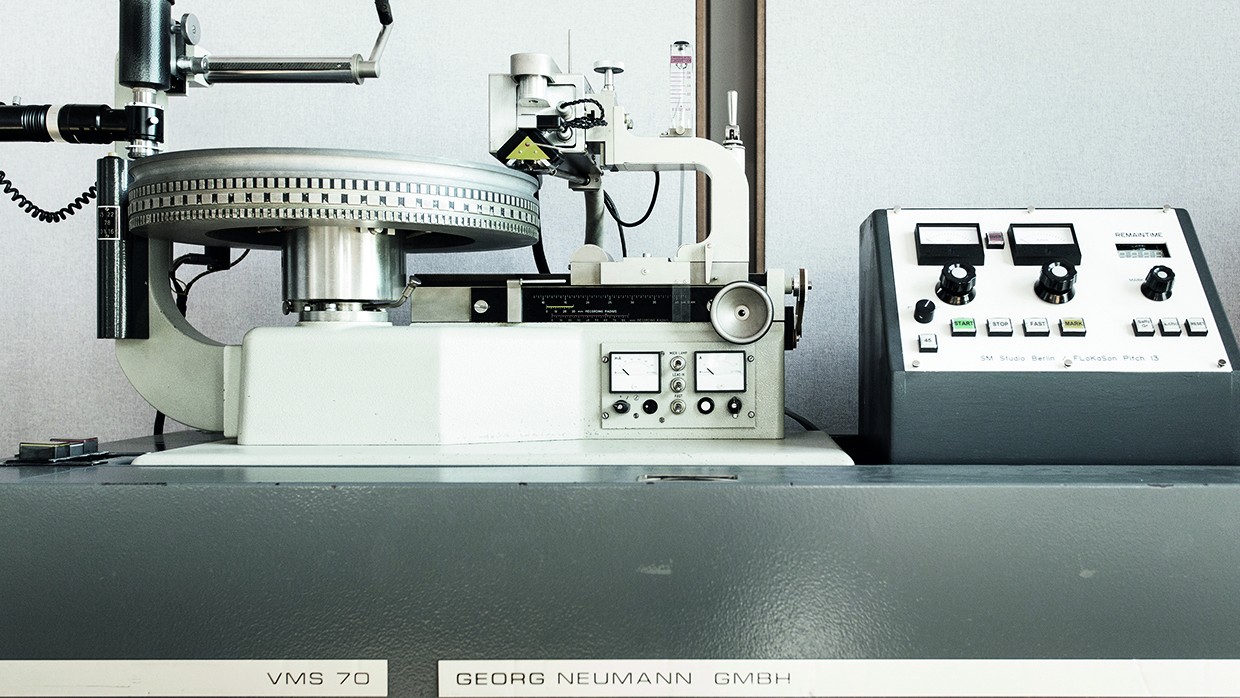

You also have a vinyl cutting lathe. Are these in big demand now due to the vinyl resurgence?

“Vinyl has definitely come back over the past 10 years or so. It was still pretty big in the ’90s but it dropped a bit with MP3 and Napster in the 2000s. A lot of studios still have lathes actually and quite a few are trying to buy and refurbish them even though it’s super-expensive because it’s hard to get spare parts and you have to rebuild everything.

“Learning how to cut vinyl on a lathe takes time, so if you want to create a vinyl release, trust somebody who has a lathe and a mastering studio rather than someone who says they can master for vinyl and knows a friend who can cut it. That doesn’t work.”