Piezo: "I encourage deep listening - these are not good tunes to listen to while you’re distracted"

Milan-based Luca Mucci (aka Piezo) on his debut album, which pulsates with innovative sound design...

Italian-born Luca Mucci spent three years in Bristol, UK, soaking up the local music culture while working at instrument company Modal Electronics as a product specialist.

Influenced by early trip-hop and IDM pioneers Aphex Twin and Autechre, his early dancefloor productions were pervaded by elements of breakcore, with particular emphasis on rhythm and percussive sampling.

Following releases as Piezo on Idle Hands, Version, Wisdom Teeth and his own Ansia label, Mucci releases his debut full-length on Milan’s Hundebiss. Titled Perdu, the album is an extraordinarily hi-tech blend of dirty lo-fi beats and sub-frequencies, driven by Mucci’s insatiable thirst for complex sound design.

A certified Ableton trainer, his production process is a constant trade-off between creativity and technique...

Your debut album, Perdu, seems to have a strong identity, but did it take a while to find your sound?

“Thank you for saying my music has a strong identity because it’s something I’ve really struggled with. I actually thought that the music on this album might be too varied or diverse in terms of BPM and style. Some of it contains very clean, digital, bleepy stuff, but there’s also lots of distorted, almost lo-fi tunes.

"Maybe without realising it, it has an identity, but for me an album cannot have a single style because I always get bored making music and need to keep myself entertained.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Maybe it’s that the identity is an expression of a side of your personality which goes beyond its stylistic construction?

“I hope so, but trust me it’s really hard and what you’re describing to me is a constant source of pain. You know when you read reviews and they say it sounds effortless? For me, it’s the opposite and you can feel the effort behind it.

"I guess that’s how music and art works in general - it’s a constant battle between your personality and what the music actually sounds like. When you make something, it’s not yours anymore. You still apply your feelings to the music but people hear different things.”

Is the pain part due to the fact that it’s a very technical album with intricate sound design, and you’re intent on getting the detail right?

“It’s totally that. Your character always steps in between you and the music-making process. Being a perfectionist is a psychological thing and being very technical is the expression of that perfectionism. I’m not proud of that, it’s just that I’ve always been a very technical guy.

"I’m an Ableton trainer too, so I have to be exact in everything I do. The core idea of a tune, melody or eight-bar loop is always very spontaneous and liberating – and that always comes very naturally, but the weeks and months it takes to complete a tune is just pain [laughs].”

For some, the fun part of music-making ends at the mixing stage…

“It’s not about mixing it’s more about the micro sound design stuff or replaying a synth patch because it sounds too bright. I’m constantly editing to the point where I’m trying to get exactly what I had in mind - even though I’m aware that’s sometimes impossible. You can get there to a point, but what you were thinking is always a fraction of a moment or situation. To be fair, I also mix while I produce and stick an equaliser and compressor on while I’m making sounds, so mixing this album was not the most difficult part.”

What was your association with the UK, specifically, Bristol scene?

“After I graduated from my computer science degree in Milan I felt I needed to have an experience abroad. I’d been listening to Massive Attack, Tricky and Portishead my whole life, so I thought Bristol was the best choice.

"I started the Piezo project in 2013 making deep, dark dubstep, so my connection with underground bass music was strong, then I found a good job at a company called Modal Electronics that manufactured big hardware instruments with a Linux operating system. There were just five of us in the company and I was the product specialist and did a bit of customer service, either fixing bugs or explaining stuff to dealers, shops and customers. I was travelling to the US and Europe quite often and pretty much had to know everything about synths, but had no time for making my own music.”

There’s a notion that production tools are so sophisticated you can always mould a sound to your exact spec. Is that an oversimplification?

“I think it’s a bit anti-art to take that direction. At some point you have to admit to yourself that there’s a part of what you make that doesn’t depend on you. You can create your own reality but at some point you have to allow other things to get in.

"You can attain a level of perfection, which gives you more possibilities to achieve different and new sounds, but I’d rather focus on the creative part than editing something until it’s perfect.”

You’re a licensed Ableton trainer?

“I’ve been a certified Ableton trainer for 10 years. I have direct contact with the company in Berlin, and in my case that means every time there’s a new update or an Ableton event in the north of Italy I’m usually the guy that the distributor calls to be the product specialist. I have to be technically flawless, which helps because it’s such a powerful creative tool. As I explained, I graduated in computer science so my nerd tendency is really strong.”

On the plus side, every time Ableton releases an update or new product, you get first dibs?

“Yes, I got everything for free including Ableton Push and all the sound packs, so I can’t complain [laughs]. A strong marketing aspect of Ableton is that people can use it as a studio instrument, so while it can be the core of your system you’re going to end up using other gear as well. Hardware integration is a strong feature for them.”

“I’m definitely not a conceptual guy - sound design is my concept”

Max/MSP was integrated into Ableton as Max for Live. Are you a fan?

“It goes back to what I said before about the nerd hole. It’s not even a dirty pleasure because I’ve got to know Max/MSP really well through my work. Max is effectively an Ableton product, but I’ve been into all sorts of music software from Pure Data to SuperCollider.

"One thing I really want to mention about Max for Live is modulation. You can use a couple of devices like an LFO to modulate things that are not usually modulated, and that’s great as it helps me to keep my sound design organic.”

In what way does it achieve that?

“If you think about sidechain compression, one sound responds to another, so having the ability to connect stuff and modulate between sound features is important.

"For example, when you open a filter on one track you decrease the distortion on another, and I like to build those automatic ecosystems into my production process.

"The same thing happens with modular synthesizers where people tend to build these huge patches because they want things to behave naturally and automatically.”

One thing that immediately stands out is your innovative approach to percussion. That seems to be a strong focal point of your sound?

“That’s something that started in the early days of Piezo when I was making deep, tribal dubstep. Percussion has always been a fixation - I’d just take thousands of drums and percussion samples and make something with them. Again, Ableton is very useful for that because of all the drum rack stuff and features that make percussion very easy. That and sub bass are the only elements that have stayed constant throughout my music, and that’s reflected on the album, too.”

On Perdu, the perc is almost indivisible or a replacement for the melody. Why go that route?

“It’s true that I don’t like things to be too obvious rhythmically, but the other reason is that I can’t stand classic melodies, riffs, synth lines or basslines. I’ll never be able to make classic four-chord progressions with a melody on top, so have to fill the gaps with something else and that’s usually percussion or sound design stuff.

"I was definitely inspired by Autechre on that front - not the early stuff but after Gantz Graf, which I consider to be their golden period. I’m fascinated by their refusal to compromise and how they go into total isolation and started building their own systems and ways of making music - it’s so inspiring.”

One or two tracks have what some people would call an ‘ethnic’ feel, especially Interludio. What inspired the sounds on that?

“That’s a bit of a dangerous territory. Of course I’m fascinated by all sorts of sounds but I don’t want to call it an ethnic approach to sampling. These days, with the internet, I’m a firm believer that you’re exposed to so many different sounds that things are not geo-localised anymore. Maybe it’s ‘internet-ethnic’.

"Simon Reynolds talks really enthusiastically about ‘fifth world’ music. Fourth world music is Jon Hassell and all those guys, but in the internet era the concept of the fifth world came out, so I’d recommend you read something about that because it really explains my approach to sampling.

"With the track Interludio, I’m not even sure if those sounds came from a library. I’m definitely not a conceptual guy – sound design is my concept.”

On the track Stray, it’s almost as if the sounds are dripping water. How did you achieve that?

“Luckily, that’s not water, but I like that you say it feels like water because it’s what I wanted to achieve. There’s a lot of processing on that track and I remember using iZotope Iris, which enables a very creative approach to sampling because you can take parts of the sound spectrum and replay them instead of the whole sound. Usually when you mess around with spectral stuff you end up with these really watery sounds, but the percussion element was just me resampling random pitches.”

Do you see music-making as a jigsaw puzzle where you’re simply trying to explore making combinations of sounds in innovative ways?

“The way I put them together is definitely a jigsaw, yes. I don’t know if it’s enjoyable for the listener to try to decrypt that and see the structure behind it - I hope so, but a few tunes on this album, particularly the ones without a beat, were definitely built jigsaw-style.

"I encourage deep listening – these are not good tunes to listen to while you’re distracted. I know that’s a strong statement and a hard thing to ask of people, especially now, but to me this album is only worth listening to if you pay attention to it.”

On the hardware side, the DSI Tempest is a crucial part of your creative process?

“It’s the best piece of gear I’ve ever had. It sounds so unique and I’m not even talking about oscillators or filters; it’s just the way the machine works. Its modulation capabilities and the workflow are really easy to use. The best part is that despite being a drum synthesiser you can change parameters to extreme levels. A huge feature that I love is modulating the envelopes of all the drum sounds together - and because it’s analogue it sounds really raw and dirty."

The Tempest was based on a Roger Linn design, right?

“Yes, Dave Smith and Roger Linn. I know Dave quite well because we did at least five or six trade shows together. When you work in the synthesizer industry you end up getting to know each other because it’s a very small industry. I had dinner with Tom Oberheim who is one of the pioneers, but also Roger Linn, Dave Smith, and I even met Don Buchla when he was still alive.”

You have a few other hardware bits and pieces?

“I have the Korg Minilogue, which I find is more useful for live jamming sessions with friends. It’s incredibly hands on and easy to use - especially the sequencer.

"The other piece of gear I have is the Elektron Digitone. I’m laughing because it’s the exact opposite side of the spectrum. There are a lot of Elektron enthusiasts around the world, but while the digital sounds are incredibly lush and the FM implementation is perfect, the sequencer is a real struggle. I’m sure it’s just a computer in a box.”

“I want people to focus on the pure perception of sound rather than how it was made”

Perhaps unusually considering its addictive nature, you only have one modular device?

“My modular row only has Clouds in it as I had to sell a couple of modules when I ran out of money. That’s always on my Ableton returns and I’ve created a template where I can just open it and use Clouds as a reverb or delay.

"It’s the same with the Sherman Filterbank. You can use it on insert, but it’s interesting to use it on parallel because you can send all the drums or percussive stuff and get a very quiet but distorted layer of dirt. Sometimes I’ll use it as a mixing tool to add a little bit of extra analogue filter.”

What are you mostly using for sound generation in the box?

“Mostly the Convolution Reverb on Max for Live. I’m not just using it as a reverb but a creative tool to get really strange sounds or add some space and depth without things sounding too reverberated.

"I also love iZotope Trash - it’s just insane because half the time you don’t know what the fuck is going on.

"I love physical modelling, particularly a company called AAS, which does some instruments for Ableton including Collision and has its own plugin called Chromaphone. There’s one track on the album called Blight Light Mama Magic where you can hear all this percussion but it’s all made by synths. That was a real sound design project as I was trying to make a tune without samples that still sounded percussive.”

Do you find it’s a struggle balancing the technical and emotional aspect of your music?

“It is difficult as I’m living in this constant balance of having to explain everything to people through my job and the freer, more artistic side of music-making. I really want people to focus on the pure perception of sound rather than how something was made. Ultimately, when a sound gives me a particular feeling, communicating the technique is not that important to me.”

Piezo’s debut album, Perdu, is out now on Hundebiss Records. Listen via Bandcamp.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

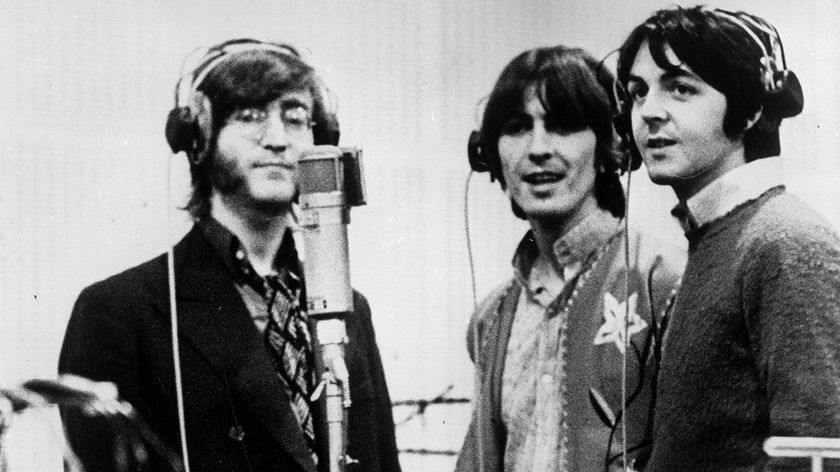

“I didn’t even realise it had synthesizer on it for decades”: This deep dive into The Beatles' Here Comes The Sun reveals 4 Moog Modular parts that we’d never even noticed before

“I saw people in the audience holding up these banners: ‘SAMMY SUCKS!' 'WE WANT DAVE!’”: How Sammy Hagar and Van Halen won their war with David Lee Roth

![Chris Hayes [left] wears a purple checked shirt and plays his 1957 Stratocaster in the studio; Michael J. Fox tears it up onstage as Marty McFly in the 1985 blockbuster Back To The Future.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/nWZUSbFAwA6EqQdruLmXXh-840-80.jpg)