From orchestras to Aphex Twin: the beginner's guide to Philip Glass

He might be the face of minimalist music, but Glass's kaleidoscopically diverse oeuvre is anything but sparse. Ahead of the release of a lavish new boxset of his piano etudes, we look back at his illustrious career

When many people think of classical music, they think of ancient institutions, backwards attitudes and fusty old traditions.

Though there may well be a grain of truth to this preconception, it misrepresents a musical sphere that’s expanded exponentially over the past few decades, as the boundary between classical and popular culture has crumbled and influence has begun to flow freely between both sides.

No composer has done more to facilitate this flow than Philip Glass. One of the most celebrated and influential figures in both 20th and 21st-century music, Glass has achieved that rare feat of connecting classical traditions with the contemporary, the avant-garde, the electronic and the popular.

His work has been performed by the world’s most prestigious orchestras, yet he’s collaborated with Aphex Twin, David Bowie, Leonard Cohen and Mick Jagger, scored Oscar-nominated films (and an episode of Sesame Street) and even remixed an acid house track.

On a smaller, more personal scale, Glass also spent more than two decades composing his Piano Etudes, which he said he began writing in a bid to expand his technique as a pianist. Work on these started in the 1990s and was only finished in 2012, when the 20th etude was completed.

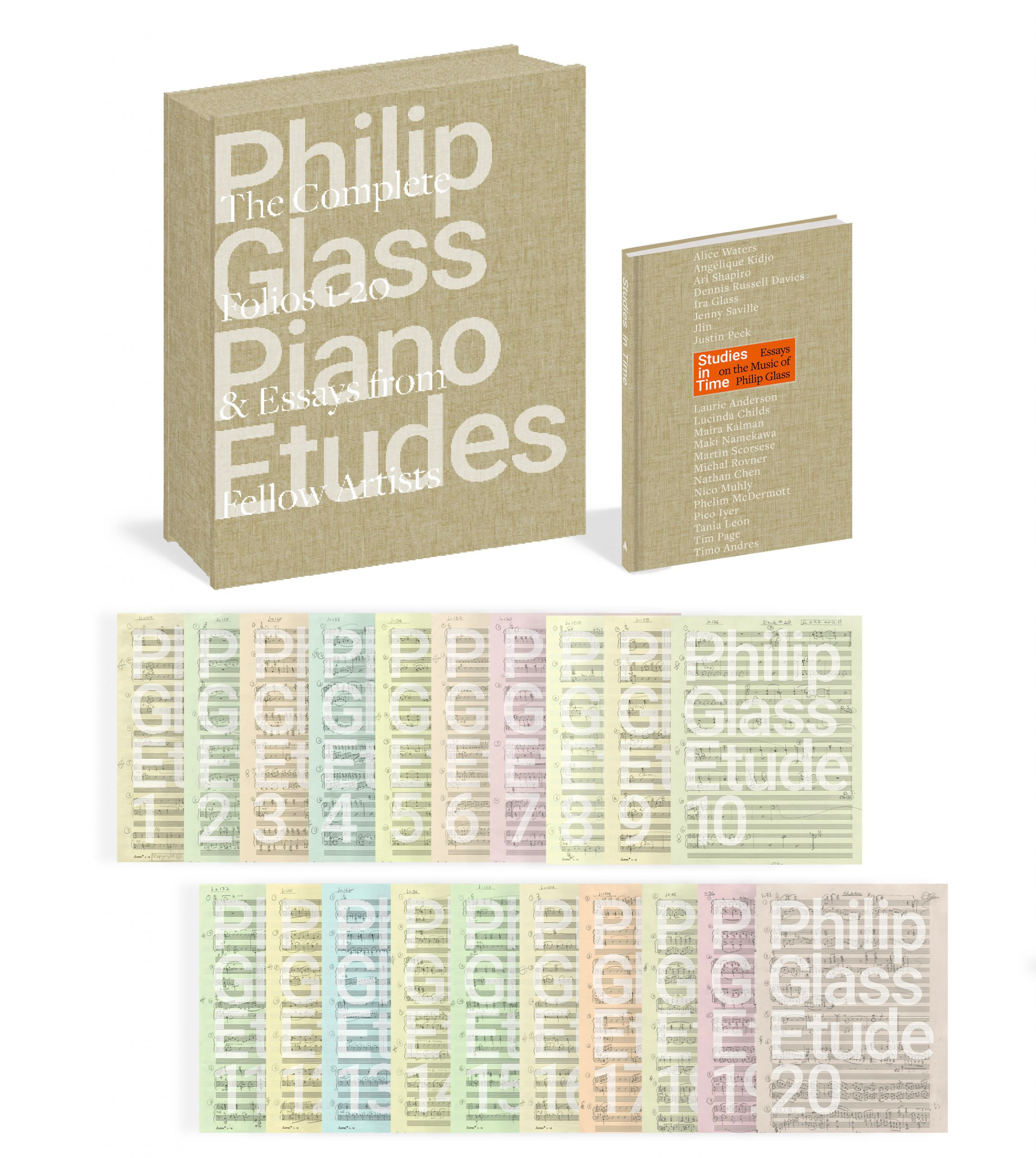

All the etudes are now set to be released together as a clothbound boxset that contains not only newly engraved folios, but also a hardcover book, Studies in Time, that features essays on Glass’s music from the likes of Nico Muhly, Timo Andres, Maki Namekawa, Alice Waters, Angélique Kidjo, Ari Shapiro, Ira Glass, Justin Peck, Laurie Anderson, Martin Scorsese, Pico Iyer, Jenny Saville, and Nathan Chen.

To celebrate the upcoming release of this sumptuous package - available from 7 November, priced at $150 and published by Artisan Books - we’re taking our own look back at Glass’s career, music and lasting influence.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Born in 1937, Glass studied at the prestigious Juilliard School of Music in the ‘60s before decamping to Paris on a Fulbright Scholarship to study under renowned conductor and teacher Nadia Boulanger. It was here that fate placed Glass in the path of composer and sitar virtuoso Ravi Shankar, a meeting that he described as the closest he’d ever come “to a moment when the creative light suddenly turns on”. That moment would upend Glass’s musical thinking and reorient his ambitions in an entirely new direction, enlightened by the cyclical, rhythmically additive nature of Indian classical music.

Uniting this influence with his grounding in Western classical and a handful of new ideas cherry-picked from serialism and the flourishing ‘60s avant-garde, Glass began to develop a musical language that, alongside the work of contemporaries such as Steve Reich and La Monte Young, would ultimately be named minimalism, a term Glass would later reject.

Minimalism prized rhythm above all else, focusing on hypnotic ostinatos and arpeggios that would repeat in fractured, asymmetrical patterns over slowly shifting tonal centres. To many, Glass is the face of minimalism, but describing Glass as merely a minimalist does a disservice to his kaleidoscopically diverse oeuvre, which itself is anything but minimal.

Nothing is off-limits in Glass's wide-ranging creative vision, and the composer’s works have been inspired by everything from Eastern spirituality to Leonard Cohen’s poetry and his opposition to the Iraq War.

From Paris, Glass ventured to India, then returned to New York, setting about developing his newly discovered ideas into a bold and idiosyncratic style. His progression through the ‘70s and into the ‘80s, ‘90s and beyond was marked by adventurous experimentation and a willingness to apply his talents to a multitude of musical forms; symphonies, concertos, chamber music and solo piano works were followed by music for theatre, dance, film and television, as Glass’s profile began to grow. Nothing is off-limits in his wide-ranging creative vision, and the composer’s works have been inspired by everything from Eastern spirituality to Leonard Cohen’s poetry and his opposition to the Iraq War.

As Glass’s career flourished, his influence extended outward into pop, rock and, perhaps most notably, electronic music. Although Glass has never composed a purely electronic piece, many of his performances and recordings have incorporated synthesizers, amplifiers and various pieces of music technology.

Moreover, Glass’s works with acoustic instruments often have the feeling of electronic music; their repetitive, mathematical structures almost sound as if they were sequenced, rather than notated on paper; their insistent, mechanical pulse recalls the perpetual thud of the dance floor; and the hypnotic state they evoke feels ambient by nature.

Glass made full use of creative production techniques when recording his orchestral works: in his memoir, Words Without Music, he recalls blending synthesized sounds with orchestral instruments in the studio.

“A trombone part might have an electronic part added to it an octave below what was originally played,” he says. “On the final mix of the record, instead of hearing a trombone, the listener is hearing something more like a super-trombone. Applied to the whole orchestra, the result is a sound beyond anything an orchestra could play live.”

Glass’s electronic experimentation extends further than many would expect, reaching its peak in 1988 when the composer worked with Kurt Munkacsi to remix S’Express’s club-focused Sly & The Family Stone cover Hey Music Lover. In an interview with Red Bull Music Academy, S’Express’s Mark Moore recalls talking over the remix with Glass, who asked to be brought along to a club night in order to better understand the music he was reworking.

“I remember driving up there,” Moore says. “We’re just like, ‘We better tell him… Philip, we just wanna explain to you – we hope you don’t get upset or anything – but we’re going to take drugs. We’re gonna take some ecstasy…’ And he was going, ‘Oh, you young people think you’re the only people who’ve done that sort of thing.’ And he insisted on joining us.”

If anything encapsulates Glass’s willingness to venture beyond the boundaries of his classical roots into uncharted creative territory, it’s probably the mental image of the then-52-year-old composer, a giant of modern music, dropping a pill and having it large at an acid house rave, all in the name of research. Philip Glass: a legend in every sense of the word.

Four of Philip Glass's most iconic works

1. Philip Glass - Music in Twelve Parts (1971-1974)

A set of 12 pieces written over three years, Music in Twelve Parts was written for the Philip Glass Ensemble, a group founded by Glass to serve as the performance outlet for his works. Glass has described Music in Twelve Parts as “the end of minimalism” in his musical progression and the beginning of what he describes as a “post-minimalist” approach to composition. "I had worked for eight or nine years inventing a system, and now I'd written through it and come out the other end,” he says.

2. Philip Glass - Metamorphosis (1989)

One of the purest distillations of Glass’s musical personality, this five-part solo piano composition is inspired by Kafka’s famous 1915 novella of the same name and was originally composed for a staging of the story. One of Glass’ most widely beloved works, it strips back his style to its most fundamental elements, as cascading arpeggios and rousing chords rise and fall above hypnotically repetitive basslines.

3. Philip Glass - Koyaanisqatsi (1982)

Koyaanisqatsi is an experimental film released in 1982 that explores the relationship between humans, nature and technology. Glass’s grand, portentous score for the film was his first, and masterfully employs brass, strings, synths and choral textures to lend emotional weight to Koyaanisqatsi’s compelling message.

4. Aphex Twin - Icct Hedral (Philip Glass Orchestration) (1995)

A meeting of two of contemporary music’s most gifted minds, Philip Glass’ Icct Hedral rework is an orchestral take on Aphex Twin’s paranoid-sounding original. The story of the collaboration was told in our very own Future Music magazine when we interviewed the pair in 1995.

“What I heard in his music was the intention to discover a different mode of expression,” Glass says of Aphex. “Whether he reads music or studied at the conservatory isn’t important. This is a guy who began building his own synthesizers when he was a boy, putting pieces of junk together, making sounds and turning them into music. That’s interesting to me.”

MusicRadar is the number one website for music-makers of all kinds, be they guitarists, drummers, keyboard players, DJs or producers...

- GEAR: We help musicians find the best gear with top-ranking gear round-ups and high-quality, authoritative reviews by a wide team of highly experienced experts.

- TIPS: We also provide tuition, from bite-sized tips to advanced work-outs and guidance from recognised musicians and stars.

- STARS: We talk to musicians and stars about their creative processes, and the nuts and bolts of their gear and technique. We give fans an insight into the craft of music-making that no other music website can.

- Ben RogersonDeputy Editor

“The most musical, unique and dynamic distortion effects I’ve ever used”: Linkin Park reveal the secret weapon behind their From Zero guitar tone – and it was designed by former Poison guitarist Blues Saraceno’s dad

“Nope, it’s real”: Jack Black and Keanu Reeves both confirmed for upcoming Weezer movie