"The choices are endless - on every laptop you have access to every sound you could ever want. That can make creativity really hard": Sean and Isom of Foster The People on new duo Peel

Forging a close bond as two-thirds of international superstars, Foster the People, Sean Cimino and Isom Innis have embarked on a parallel life as Peel. The pair’s debut LP Acid Star showcases the breadth of their unfettered sonic ambitions…

For most artists on the cusp of the release of their debut LP, a simultaneous learning experience takes place, as the mechanics of the industry are absorbed. The promotional responsibilities are often a surprise to artists who’ve spent the previous few years toiling away in solitude.

Not so for Sean Cimino and Isom Innis, names recognisable to fans of Foster the People – an act that, since 2010’s viral mega-hit Pumped Up Kicks, have become a household name. For Cimino and Innis – who joined frontman Mark Foster initially as touring members back in 2010 – being plugged into the universe of promotional responsibilities is something they’re all too aware of.

However, the pair’s new side-venture finds the multi-instrumentalists exploring altogether more sonically diverse terrain, with their inaugural LP Acid Star, the duo – in the guise of Peel – juggle their gift for melody with alluring beats and lush synth ornamentation. We ask the pair where Acid Star’s ten tracks originated? “I think it first began late 2020, actually,” Sean tells us. “Isom and I were both in different places during that time. I was in Northern California, and Isom was in Austin.

The song Manic World was pretty much finished later that day. A lot came out of those three days, it was wild

“We had an EP called Rom-Com that came out during that time, but we were still feeling creative. I’d be writing where I was at, and Isom would be writing where he was at. We’d send each other stuff back and forth. In December 2020 we both met up in California, and went to my brother Nathan’s studio in Costa Mesa. We had a three-day session and came up with the foundational groundwork of the tracks that made up the album. All these grooves and melodic ideas. It stemmed from there.”

Isom continues: “In those first three days, I feel like we opened up a channel. A lot of ideas flowed through. At that time, we didn’t know that we were working on an album, we were just doing it for fun and experimenting around. We left the studio with a bunch of different ideas. At that stage, a lot of it was built from drums and drum machines.

“We have a process of working, where we’ll improvise together where Sean is playing a drum machine, and I’m playing live drums – we’ll let those takes run for sometimes three minutes, but we just kind of improvise and move on to the next thing. By the time we left we had all these different rhythmic tracks. Then, the next process was listening back, and deciding which pieces we wanted to work on.”

At this stage, the two men were guided by the spirit of fun, with around 70% of the music being rhythmic in nature. Album tracks such as OMG and Y2J were quickly birthed in that period. “The song Manic World was pretty much finished later that day. A lot came out of those three days,” says Sean. “It was wild.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The acid test

Amongst the vivid colours on the record, lay the ethereal synth clouds that shadow Manic World and Pavement’s bubbling arpeggios, not to mention a fierce synth bass that rears its head throughout the record. We wonder if a lot of this was virtual and how much was hardware? “Both!” Isom quickly answers. “The primary instruments were the Roland JUNO-106 and the Sequential Prophet-6. Those are our workhorses. We got so much use out of them, and we love those synths so much. We used a Moog Sub Phatty for the bass and then so many different software instruments. In particular, Arturia’s stuff,” says Sean.

“Their Mini V is amazing, as are their Prophet-5 V and their ARP2600 V. We probably put a million plugins on it to make it sound as warbly as possible,” says Isom. Sean adds: “One of our approaches with synths is stacking. We program MIDI and then run it to the Moog, then run it to the Prophet. We’d just stack different sounds. In The Sedantary has a Moog bass that is three different sounds from that Moog. We’d just perform it and create just a really unique sound that you couldn’t replicate if you tried.”

Sean reveals that despite the software-generated textures on Acid Star, his background as a pedal-hoarding guitarist makes him savour the knob-twiddling joys of hardware a little more: “I’m constantly on the floor, tweaking pedals and I like the feeling of that. But, yeah, what computer software can do now is just mind-blowing. The things that Isom would achieve with synthesis and dialling in sounds from the Arturia plugins just sounded so good.”

For the song Pavement, I was trying to emulate the A Clockwork Orange score by Wendy Carlos. It’s really baroque sounding

The ominous synth bass took its cues from one of electronic music’s first pioneers: “For synth bass, we moved between the Moog and the Juno-106. For the song Pavement, I was trying to emulate the A Clockwork Orange score by Wendy Carlos. It’s really baroque sounding.”

Isom tells us that his primary instruments are the drums and piano, whereas Sean is guitar and everything that goes along with guitar. “I love collaborating on anything synthesis, because I feel like when tweaking analogue or modular synths, Sean has an amazing brain for sculpting sounds. It’s the same with his pedalboard, he’ll go in sonically and shape synth sounds in a similar way. Finding all the different patches and tweaking oscillators – it was amazing just watching him and letting him go. It’s interesting because I think that foundational instruments will inform the way that you then approach other instruments…”

One of the things I love about Ableton Live is that automation is so precise

We ask Isom about his approach to working with disparate synth elements in the box. “We started the record in Logic and then finished it in Ableton Live. One of the things I love about Ableton Live is that automation is so precise. With all the analogue synths – you can’t really automate them in the same way. That perfectly controlled automation. What we ended up doing is taking both hardware and software synths and layering them together, where you can be so detailed.

“I was trying to treat a soft synth like it was an oscillator of an analogue synth, where maybe the main warmth and texture comes from the analogue – but the high-end and the resonance and sweeps in the release. The more precise stuff is coming underneath from a soft-synth, where that automation can be tighter. You play them together and you get a super-sound!”

True faith

On the subject of influences, the record’s retro-leanings certainly evoke the spirit of the stable of Factory Records, and those ’80s rock/dance crossover acts that helped bridge the gap between the then murky, club-based world of electronic music and chart-friendly rock/pop. We wonder if these were conscious reference points? “[The sound] was definitely dictated by our influences,” says Sean. “It’s funny, I feel like on our EP, we were definitely living in this very post-punk, Manchester-based 1970s vibe.

“Now it’s just evolved into the 1990s rave culture of what was going a bit later. It’s stuff that I love personally. I don’t think it was super intentional, but it was things that Isom and I were really on about and are still exciting to us. I’ll still listen to those Joy Division or New Order records, and it excites me even today. Whether that’s just nostalgia or it being really genuinely great music, I don’t know. But those things are all in our DNA, 100%.”

Though we’re using Logic and Ableton, we’re trying to limit the choices and trying to approach it how a classic band would

Isom reflects further: “Acid Star is more influenced by that next era, when technology was more widespread and got introduced more in those bands’ music. I think there’s something about primitive technology before computers were central. For me, just as a fan, when I listen to some of that music – the choices are so bold and I think that’s because choices were limited. Where music is right now, is that choices are endless. On every laptop you really have access to every sound you could ever want. For me, that can make creation really hard sometimes.

“To make a hard choice is often overwhelming and anxiety-inducing,” says Isom, “But, yes, the meshing of post-punk with technology is an era where I feel drawn to. We’re both really into Martin Hannett – the producer of a lot of those records. There probably weren’t even that many synths in that studio, but the way they incorporated the Moog in their early work, I find really inspiring. Though we’re using Logic and Ableton, we’re trying to limit the choices and trying to approach it how a classic band would.”

Aside from the synths, the record is a rhythmic tour-de-force, spanning the trip-hop breaks that pepper OMG to the four-to-the-floor club-filling momentum of Mall Goth. The beat programming was driven by Isom’s obsession with the process: “A lot of those tracks came from that early three-day session. With those two tracks, we were just messing around and doing the improv.

“Sean was in the control room programming the drum machine and I would be in the live room with the drum kit, just responding to it. We did that for a bunch of different songs. Mall Goth and OMG both started as rhythm tracks and we jammed over the top of them for around 10 to 20 minutes. I remember specifically listening back to both of those, and they had a lot of energy. I cut them down and arranged them into more of a loose structure.”

I love the way a drum machine and live drums sound when they play together, but I hate the way they sound if they clash in the low-end

Isom continues: “The thing with recording to a drum machine is that it’s a little bit counter-intuitive, unless you’re the best drummer in the world. When I’m trying to play along to the drum machine, my performance will push and pull a little bit. Sometimes it’ll be more on the beat than others, but usually what I’ll do is that I’ll edit the drums a little bit. I can be really critical with the low end and the punchy-ness.

“I love the way a drum machine and live drums sound when they play together, but I hate the way they sound if they clash in the low-end. I made sure to really edit the kicks. I also side-chained the drum machine to the live kick. Sometimes I would remove the low-end of the drum machine, and sometimes there wouldn’t be low‑end in the drum machine, and would be more mid and high/mid.

“My favourite and least favourite part of the process is getting the drums right. It’s probably what I obsess over the most. It’s a never-ending cycle of trying to get the right drum sound. I go pretty deep on that. The initial edit was on Logic, then I put both these songs into Ableton Live. I love the way you can process drums in Live, so I further fine-tuned it there, as well as experimented around with additional sounds.”

Riding the song

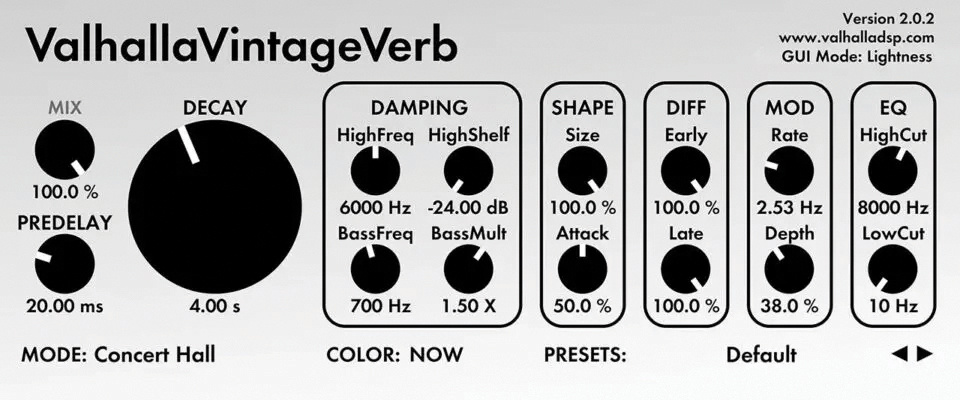

Peel’s use of spatial effects – notably on the album’s title track, which stretches the lead vocal out seemingly infinitely – is a key ingredient. But, what tools and techniques were deployed to manipulate virtual spaces? “For that [the track Acid Star], it was a combination of the Goodhertz, Inc’s Megaverb, and I’m such a fan of the Valhalla DSP VintageVerb.”

“To get that specific sound I remember putting a little bit of ’verb on it, but what I did was reversed the vocal, then stacked it underneath. Then I played with the ’verb on the reverse vocal. That reverse aspect is just as important as the reverb. The more textural element is probably the reverse mixed with the vocal. It was really a duplicate tucked underneath,” explains Sean.

It’s a special song for Isom, who remembers when Sean brought it to him in its early form: “I remember when Sean showed me it initially he was just playing it for me in the room. He was singing the early melodies and the chorus. When the song starts it’s very intimate and it’s very classic. I feel like, for me as a listener, I can guess how the whole thing’s going to go – you might imagine it following quite a conventional path.

One of my favourite parts about that song is that it starts in such an organic, intimate place and then it slowly morphs into something completely different. If you’re in for the ride with that song, then it takes you to a completely different place. To me, the reverb is approached like a synth. Acoustic guitar and synth together, for us, was a hard thing to coexist and feel natural. By the end of the song, I think we figured out a way to present those sounds in a way where they complement each other. It ends in this spacey, ’80s, wonky dimension.”

“I think that Isom is a genius in the synth work on the song,” says Sean. “I remember on the bridge, that synth-hook line came really early in the process. I think it was on Teenage Engineering OP-1, actually. We were in my wife’s studio apartment, while my wife was working we were working on the song and Isom was just in the hallway and came up with that. He built off of those arpeggiated synths at the end.”

With album #1 a solid statement of creative intent, we enquire as to whether Peel’s future is mapped out? “We’re always interested in different music at different points in time. We’re also in Foster the People, and so with that, we’re always digesting culture. But [with Peel], it’s such a synergy that he and I have for this project. I think it’s different lenses and wherever we’re at, at the time, will dictate what kind of music we make.”

Right now I feel pretty empty. I don’t know where that next creative spark is going to come from

Isom is a little more technically specific on how he’d like to build album #2. “Acid Star was such a creative purge and right now I feel pretty empty. I don’t know where that next creative spark is going to come from. With Acid Star, there were two things we were trying to chase that I feel we at least kind of achieved. One of them was incorporating the dance inspiration in the drums, but having that come from an organic place. Filtering dance music – which is primarily made with machines – through an organic drum performance. With four-to-the-floor, more traditional dance-sounding BPMs but also with more breaky, half-time level (as trialled on OMG and Cycle).

“My strength and weakness is that I love drums so much that I just want to process them into oblivion. I enjoy processing the drums so much. At the beginning of the song it sounds so energetic and exciting just crushing drums and compressing, but I run into this problem, which I’ve encountered on every record I’ve worked on. I over-process it [in isolation], so by the time we come to writing the vocal, the drum processing is taking up so much space.

There’s something about having songs that move a crowd, and there’s a symbiotic relationship going on

“When you’re assembling all the sonics, everything needs its own place. So, I have to work backwards, and take some of that information out of the middle and the high frequency ranges. Whenever that happens it feels like a little death; I have to dial it back.”

Playing live to global audiences as Foster the People, and getting into the circuit now in renewed form as Peel, we wonder if the pair prefer the stage or the studio? “When you’re recording you don’t get immediate feedback, but on-stage you do. There’s something about having songs that move a crowd, and there’s a symbiotic relationship going on. It becomes its own language, its own art form,” explains Isom.

“The pandemic took that relationship away, and made me realise it was to the process. Sean and I have played live together so much that it is an extension of our psyche. I think in the past I might have said the studio is where I’d rather be, but where I am sitting right now, is that it’s equally important and they both inform each other.”

Peel's Acid Star is out now on Innovative Leisure.

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.