"George Martin knew Robert Moog, and asked him to come to Abbey Road and show us this Moog thing": Paul McCartney on the synth used on the final Beatles album and how its 'noise' created tension in the band

Did the Moog synth speed up the demise of the Beatles?

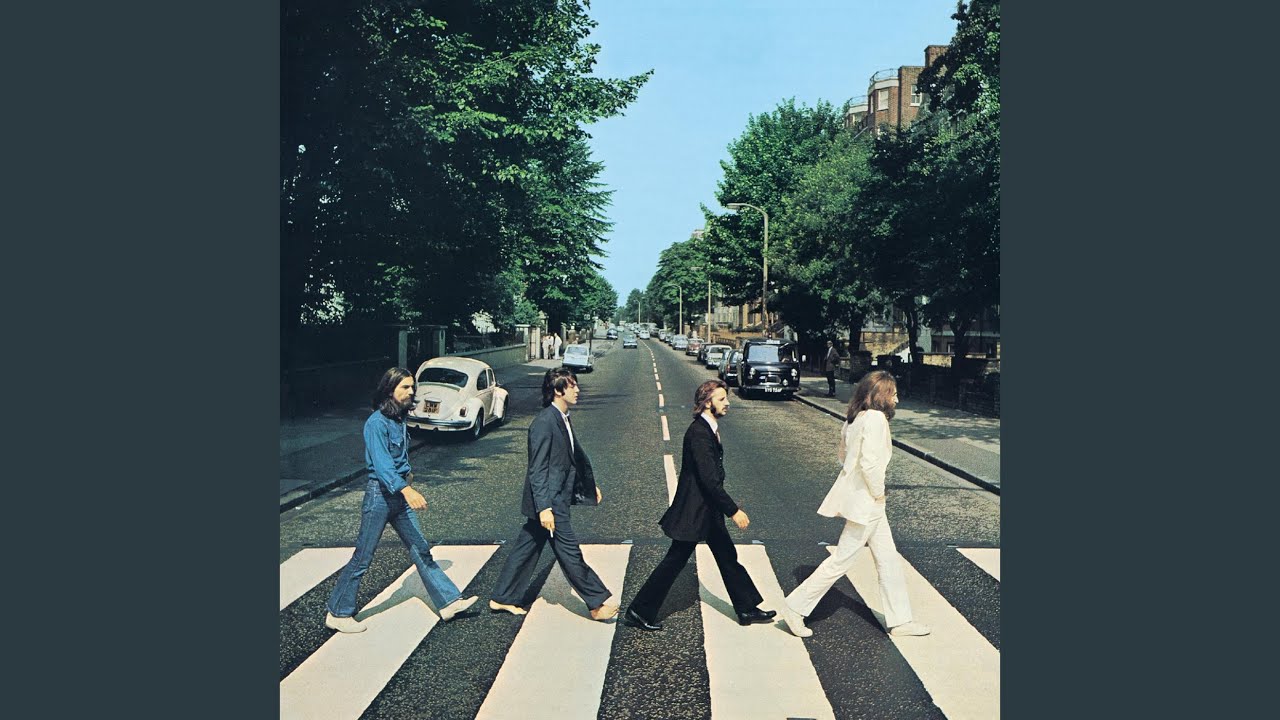

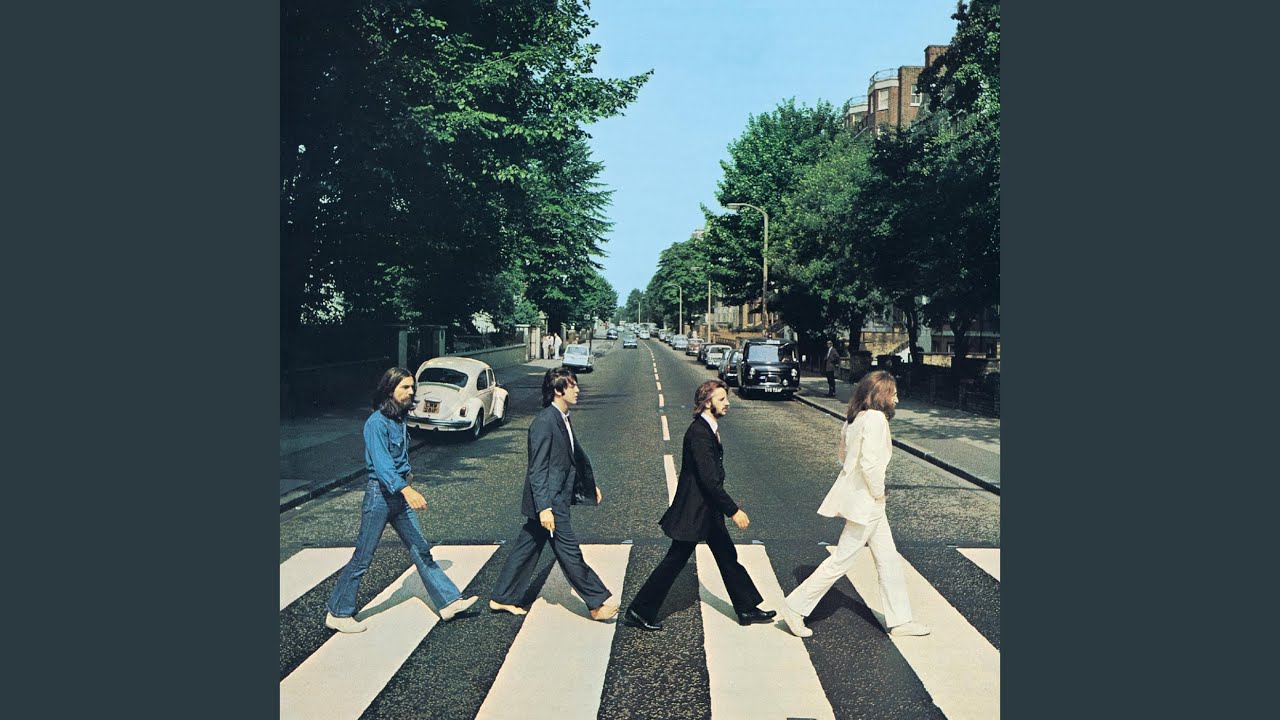

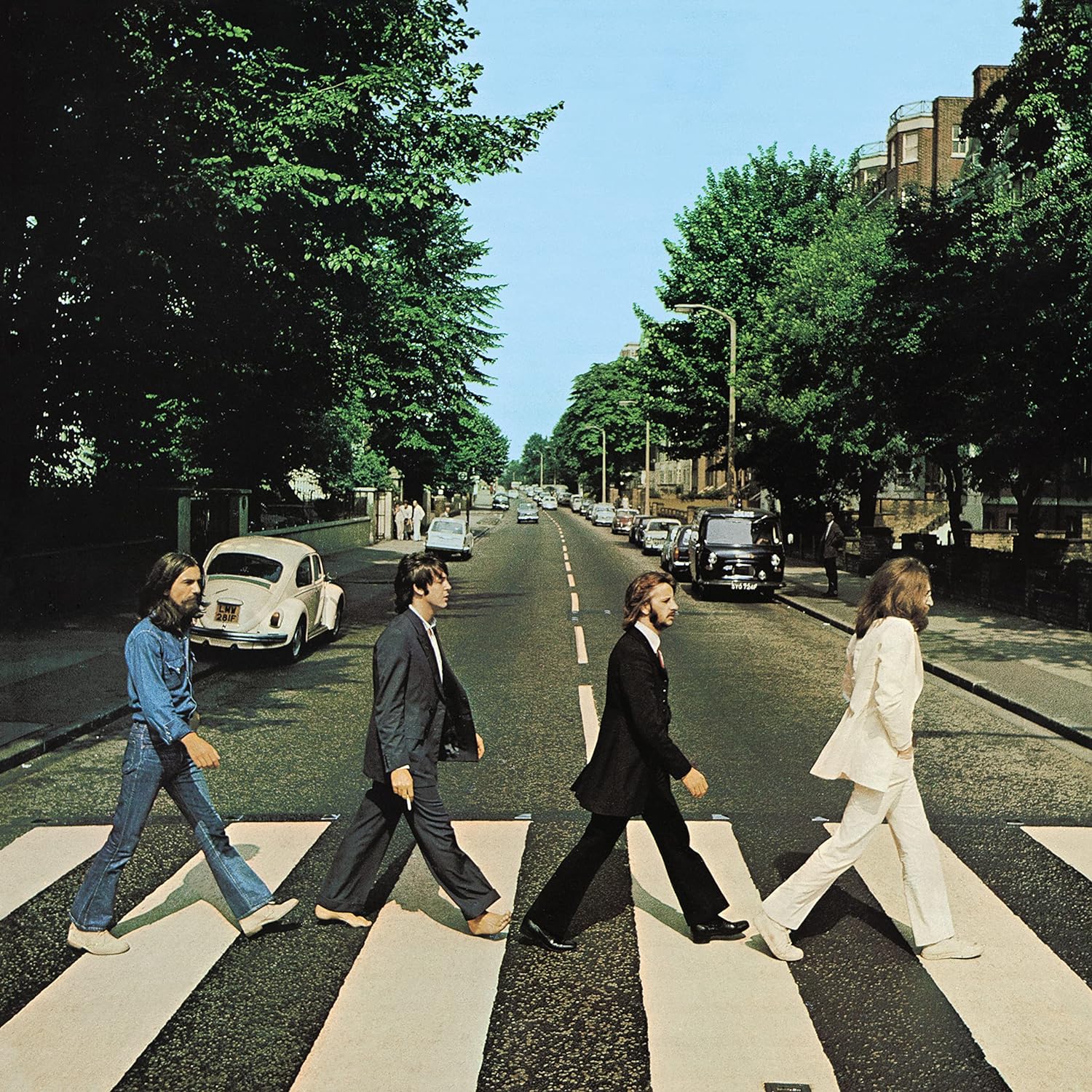

The 1969 Beatles album Abbey Road is famous for many things: the cover photo of The Beatles on the zebra crossing walking away from the studio, the fact that it was the last album they recorded, and because it was the first time the band had ever used a synthesiser.

What is less well known is how various members of The Beatles embraced the synth during the Abbey Road sessions, and how one of its key sonic features might well have contributed to the demise of the band.

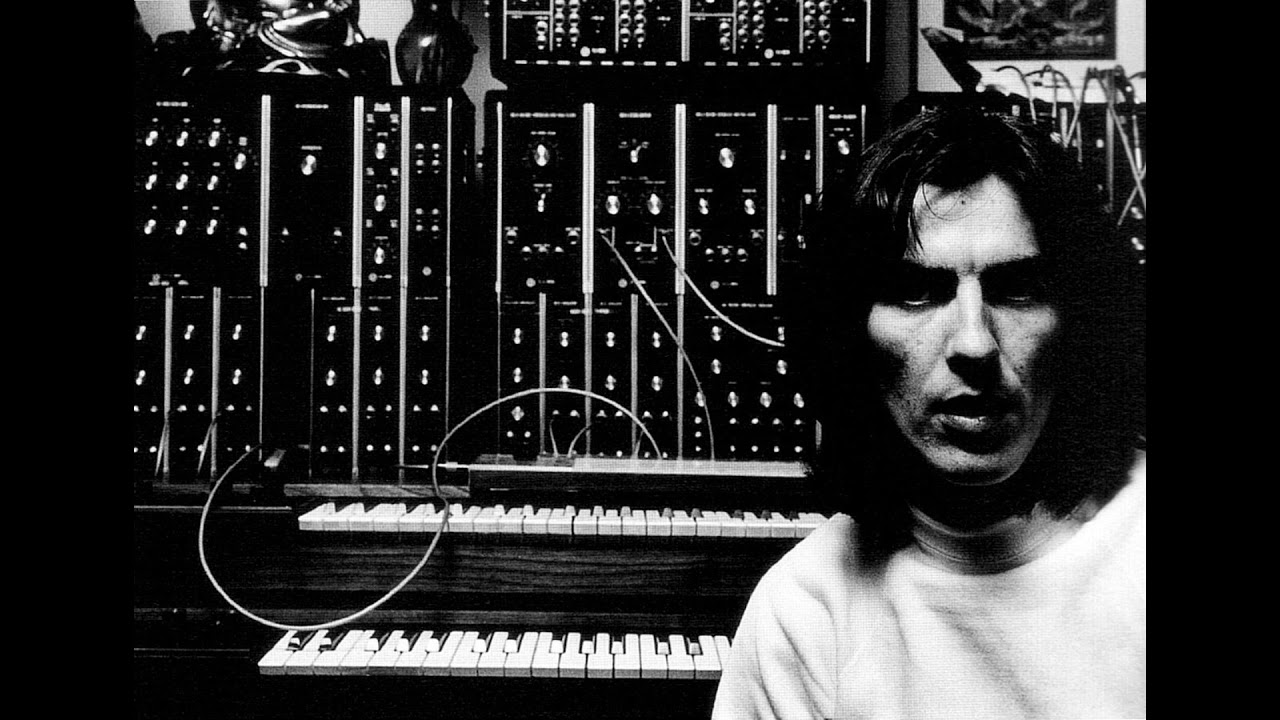

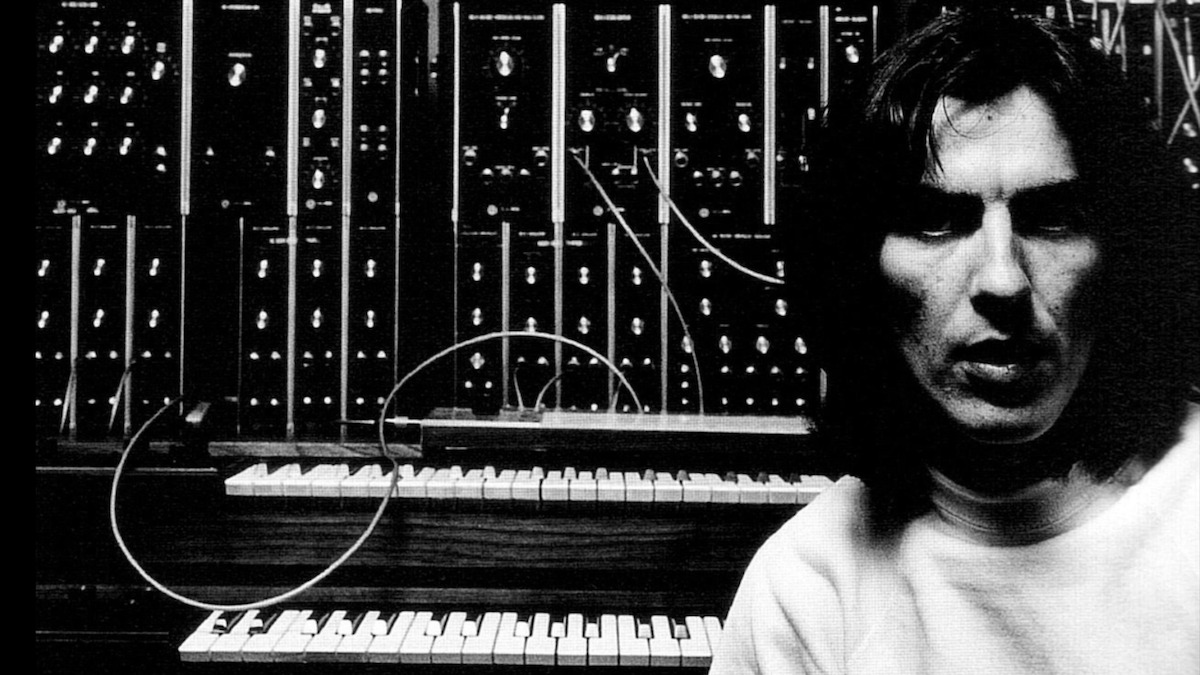

There are slightly differing accounts as to how the modular Moog 3 arrived at Abbey Road. According to Geoff Emerick, Moog had given a demo of the synth at EMI Studios some months before the recording of Abbey Road, and the band were impressed enough to use the synth.

No one had seen synthesisers. This was the very first time, and it took up a whole room.

Paul McCartney

And in a recent McCartney: A Life in Lyrics podcast, Paul seemed to back this version of events up, saying that his recording of the track Maxwell’s Silver Hammer on the Abbey Road album "coincided with the visit of Robert Moog, the inventor for the synthesiser. No one had seen synthesisers. This was the very first time, and it took up a whole room.

"It was a huge thing," McCartney added, "and it filled a whole wall of the room. George Martin was always very keen on these technological innovations. You'll probably find he knew Robert Moog, and he went 'Moog come over to Abbey Road and show us this Moog thing'. I was fascinated and he would show us how to get these sounds. But it took a little longer than our normal songs took."

However, a slightly different version of the story is that the synth used on the Abbey Road album actually belonged to George Harrison. He'd been in Los Angeles the previous November (1968), producing the album This What You Want? by Jacki Lomax, during which Moog salesman Bernie Krause demo'd the Moog modular synth simply known as '3'.

A foreboding black object the size of a bookcase…

Geoff Emerick on the first Beatles Moog

This was one of the first commercially available synthesisers but not exactly easy to handle nor transport – "a foreboding black object the size of a bookcase," according to Emerick. Nevertheless, it was an instrument that a few high profile musicians had started to use, including Byrds front man Roger McGuinn, and the cheekiest of the Monkees, Micky Dolenz.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Harrison was quick to adopt it too, using sounds from the Moog on his 1969 solo album Electronic Sounds, in particular the track No Time Or Space, effectively a 25 minute demo of the Moog modular.

Harrison would later buy the Moog system which could be bought in varying configurations for around $15000, aka a heck of a lot of cash in 1969.

Mr. Moog had only just invented it. But it was one thing having one, and another trying to make it work.

George Harrison

“I had to have mine made specially," he said in The Beatles Anthology, "because Mr. Moog had only just invented it. It was enormous, with hundreds of jack plugs and two keyboards. But it was one thing having one, and another trying to make it work.

"There wasn’t an instruction manual, and even if there had been it would probably have been a couple of thousand pages long. I don’t think even Mr. Moog knew how to get music out of it; it was more of a technical thing."

According to MusicAficianado.com, Harrison's system included "two five-octave keyboards with portamento control, a ribbon controller, ten oscillators, a white noise generator, three ADSR envelope generators, voltage-controlled filters and amplifiers, a spring reverberation unit and a four-channel mixer".

And that white noise generator would prove to be his most controversial purchase…

After Harrison used the Moog on his Electronic Sounds album, he then moved it into Abbey Road in the summer of 1969. It was "packed up in eight huge boxes," according to Geoff Emerick and "took forever to set up and get just a single sound out of it. Harrison sure loved twiddling those knobs. I have no idea if he knew what he was doing, but he certainly enjoyed playing with it.”

Harrison sure loved twiddling those knobs. I have no idea if he knew what he was doing, but he certainly enjoyed playing with it.

Geoff Emerick

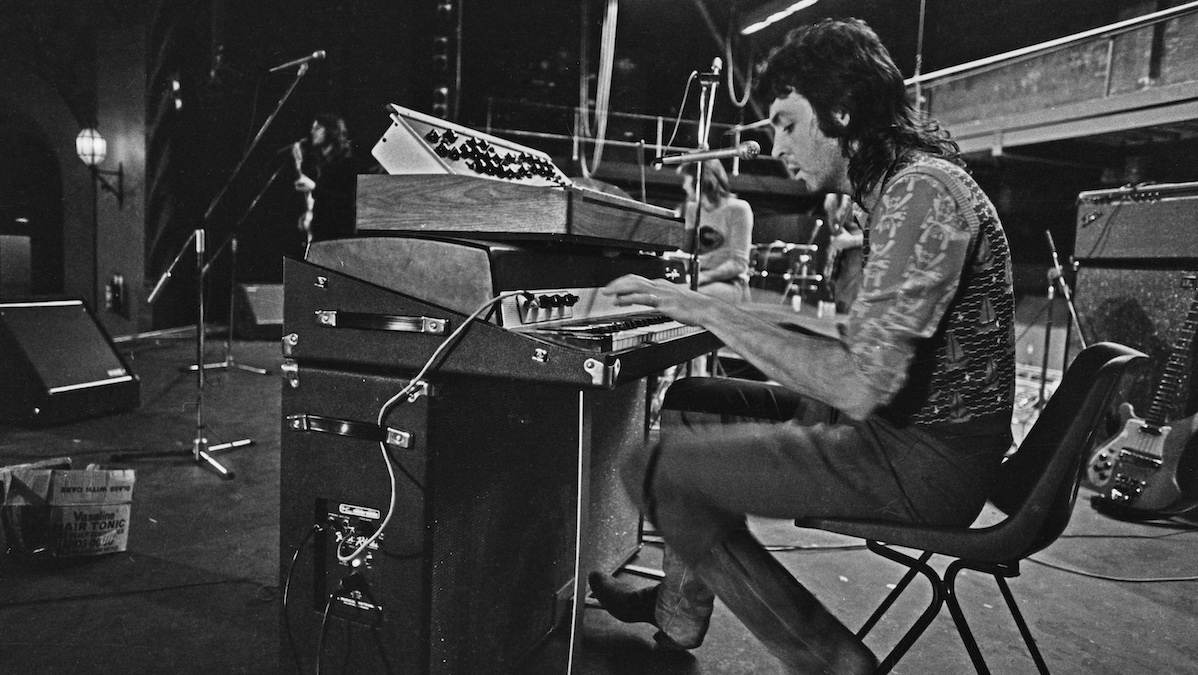

George wasn't the only Beatle to get the synth bug. While creating the various songs for their last recorded album, both Paul and John would experiment with the synth, and it ended up getting used on four tracks: McCartney's Maxwell's Silver Hammer, Lennon's I Want You (She's So Heavy) and Because, and Harrison's Here Comes The Sun.

On this latter track, the use of the Moog was less obvious, with Harrison saying in the Beatles Anthology: "when you listen to the sounds on songs like Here Comes The Sun, it does do some good things, but they’re all very kind of infant sounds."

However, Paul would use the Moog more obviously on Maxwell's Silver Hammer, a typical McCartney 'story song' about a made up killer he'd created after listening to a play called play Ubu Cocu by french writer Alfred Jarry.

The synth comes in after the first 'killing' at around 50 seconds…

As joyous as the track sounds, it's about the lead character Maxwell killing another character Joan with his silver hammer – the synth comes in after the first 'killing' at around 50 seconds, with Paul apparently 'playing' the synth using the ribbon controller rather than the keyboard.

This clip has the isolated guitar and synth from Maxwell's Silver Hammer and you can hear how varied the Moog sounded.

Lennon would be even more dramatic with his use of the synth, and according to Emerick in Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles, the Moog would end up indirectly causing some tension between Lennon and McCartney.

He started becoming almost obsessed with the sound. 'Louder! Louder!' he kept imploring me.

“George set up the Moog synthesizer at John’s request and twiddled the knobs as the great behemoth spit [sic] out white noise, tacked onto the end of I Want You (She’s So Heavy)," Emerick said in his book.

Lennon was apparently so impressed with the sound of the white noise from the Moog that he got Ringo to enhance it with a wind machine that just happened to be in the EMI Studio 2 percussion cupboard – yes, you couldn't make this up.

This white noise seemed to wake up some kind of monster in Lennon and Emerick continued: "He started becoming almost obsessed with the sound. 'Louder! Louder!' he kept imploring me. 'I want the track to build and build and build, and then I want the white noise to completely take over and blot out the music altogether.”

Emerick noted in his book that while Lennon was getting more and more obsessed with his white noise, Paul, on the other hand, was getting more downbeat with its use.

Paul was very unhappy, not only with the song itself, but with the idea that the music – Beatles music, which he considered almost sacred – was being obliterated with noise.

Geoff Emerick

“I could see a dejected Paul, sitting slumped over, head down, staring at the floor. He didn’t say a word, but his body language made it clear that he was very unhappy, not only with the song itself, but with the idea that the music – Beatles music, which he considered almost sacred – was being obliterated with noise. A gleeful Lennon seemed to be taking an almost perverse pleasure at his bandmate’s obvious discomfort."

While the synth certainly can't be blamed for the Beatles falling out – tensions were already running sky high by this point – the band only came together again for the final mix of the Abbey Road album and split up the following year.

What is obvious from The Beatles limited use of what, by today's standards, was a limited synth is how varied the sounds and use were that they got from it. From white noise to guitar plucks, more obvious synth sounds to effects, the Moog was certainly put through its paces. Not only that, but it's one of the first times that a synth was used as a regular contributing instrument rather than a novelty sound, as so many other bands used it for at the time.

So after such a wide-ranging use on Abbey Road, you have to wonder what great music the band could have made with the synth, and later more complex models, had they stayed together for one more album. Or whether they'd simply have fallen out more over some white or even pink noise. Tomorrow never knows…

Andy has been writing about music production and technology for 30 years having started out on Music Technology magazine back in 1992. He has edited the magazines Future Music, Keyboard Review, MusicTech and Computer Music, which he helped launch back in 1998. He owns way too many synthesizers.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues