Octave One on how hardware made them who they are today

Lenny and Lawrence Burden talk about the hardware behind their incendiary, live shows and their latest album Love By Machine

Detroit-born techno outfit Octave One is very much a family affair, formed around the core duo of brothers Lenny and Lawrence Burden, and joined in the studio by siblings Lynell, Lorne and Lance. The Burden brothers have been making music together since the late ’80s, both as Octave One and as Random Noise Generation, releasing music for labels including Tresor and Transmat, as well as their own 430 West imprint.

As Octave One, they’re arguably best known for their hardware-driven, heavily improvised live shows, which have seen Lenny and Lawrence stun clubs and festivals across the globe for over 15 years. With their first new album in seven years, Love By Machine, set to drop later this month, we met Lenny and Lawrence ahead of their workshop at this year’s ADE to share in a bit of machine love.

What is it that’s so appealing about working with hardware?

Lenny: “For me I like to touch things and feel things. I like the weight of the keys on a keyboard. I like those little knobs, and the way I can ever so slightly move it and get maybe a big effect or a small effect. I can’t really get that from soft synths. It just felt like ‘how can I make music with something I use to do my emails?’ It’s so bizarre to me.”

If you’ve got a diamond, why buy a cubic zirconia?

Lawrence: “It’s because we didn’t come from that.”

Lenny: “Yeah, we didn’t come from that. Software never inspired us in the beginning because that simply didn’t exist.”

Lawrence: “A lot of it too is the relationship with the machine. The different characteristics you get with them. If you come from this era, you can probably get the same kind of feeling from software, but for us it’s like, this 909, not only does it sound different but there’s a way it reacts differently. Like, a particular synthesizer has an individual way it reacts; it’s the quirks that it has, the little nuances.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I found that when we started to work with software-because we tried our best with soft synths - we found it was emulating something, rather than actually being something. It was emulating something that existed in the real world, so I didn’t feel we needed to go to an emulation when we could have the real thing.”

Lenny: “If you’ve got a diamond, why buy a cubic zirconia?”

Lawrence: “Yeah, if I have access to the real thing I’d rather have that. And even if you tell me the software can do so many other things, the limitations of the hardware might be the thing that gave me the inspiration in the first place. A lot of time that is what inspired us - those limitations.”

When you started making music, what were the first bits of gear you had and did they influence the style of music you ended up making?

Lawrence: “Yeah, they really did. Our first couple of bits were two used drum machines.”

Lenny: “We had a Kawai R50 and a Korg DDD-1. They had the crunchiest sounds. It allowed us to make drum songs. At that time, you could only afford to buy a piece of gear at a time - you couldn’t afford to have a whole studio straightaway. So I had these two pieces of gear and I did everything possible with them. You would make complete songs if you could. You’d save up six months to a year, then you’d buy a keyboard to go with that. Then you’d save up for another six months. But as you bought these pieces, you learned them inside and out. I mean, every little bit, just so you could get around them.

"The things that you wanted to do, you’d have to experiment to work out how to do it. You might want a song to swing a certain way and you couldn’t automatically do that, so you had to kind of play the swing. Back then people didn’t quantise the swing, they’d play it to make it move the way you wanted.”

Lawrence: “With those bits, we had the electronic shit coming from the R50 and then from the DDD-1 we had a percussion card and some finger snaps. What we got into was mixing the sound of electronic drums with the slightly more organic sounding drums; putting percussion with these electronic sounding pieces. That’s something that’s resonated through our entire career, based on those two machines that we originally got. We’ve always mixed those two kinds of sounds.”

When you first started performing as a band, what made you want to go down the hardware route rather than the classic DJ approach?

Lenny: “Lawrence actually started off as a DJ.”

Lawrence: “Even before we started making music, we all started DJing together. We were doing college parties, stuff like that. We played stuff like Model 500 mixed with Janet Jackson - crazy things. That probably helped develop our style. We had a deep love of the underground but we still loved little sprinkles of commercial stuff intertwined with it. Then after that I got into DJing in clubs properly.”

Don’t call it cheesy, I love that reverb!

Lenny: “The band evolution, that was actually an accident. We’d been running a record label - which we still do, 430 West - and we were putting together a tour and one of our main acts we had on the label decided they didn’t want to do the tour. We had these dates planned and we decided we needed a band, so we needed to figure this out. I came in to play live, Lawrence was DJing, we had another friend, DJ Rolando, who was DJing too, then we had another live act and I was coming in to play live under our other name, Random Noise Generation.

“Lawrence got finished DJing and I got set up to play. I had this huge table full of gear - I was even doing visuals off of an old laptop; it was crazy. It seemed like a great idea. We were playing our first date at this Detroit club, I was trying to figure out how to get it going when Lawrence just jumped on stage and got behind the mixer. Really that’s how the band was born, I never even really played live by myself for ten minutes. That was it from then on.

“As soon as we tried it, we knew that was what it was going to be. We had like, four or five dates after that where I was supposed to be a solo act, but I was never a solo act after that. Lawrence would DJ, then he’d run up to the stage and we’d play live together.”

Lawrence: “I was real amped up off of DJing and I just started working the live mixer the same way I would a DJ mixer. I’d play with EQs and mix instruments in and out. That’s how it was born.”

Tell us about the set-up you use on stage now. Do you still have those two defined roles?

Lenny: “Yeah, we do pretty much have defined roles. It’s pretty much the same as what we just described. Lawrence is behind the mixing console, which is a Midas 32. We still like the original console and not the 32 they have now, because the original is a much truer analogue mixer; it doesn’t have FireWire, doesn’t have USB. It’s also got a lot more space between the actual channels.”

Lawrence: “That means I can actually play the controls.” Lenny: “Basically, Lawrence’s set-up is a mixer with quite a few different effects. There’s an Eventide Space and the AdrenaLinn, the Roger Linn piece. He actually also has that Alesis cheesy reverb…”

Lawrence: “Don’t call it cheesy, I love that reverb!”

Lenny: “Then he has an Eventide H9 and a couple of really nice compressors. Basically, he’s the end of the chain and I’m the other part of that chain. I’m dealing with all the synths and drum machines.

“The main brain and MIDI clock for everything is the MPC1000. It’s a nice small piece and it has the JJOS operating system, which is an after-market OS that allows it to do a lot more things. We actually bring two of those so we have a back-up in case something happens to one. They both have the same programs, same OS and same information. Then we have a sampler for whenever we know we need something in a track where we can’t recreate it with a synthesizer, like the strings in our track Black Water, for example.

In the early days we thought we were being smart.

"We worked with an orchestra for Black Water, but we can’t bring an orchestra out with us live. Then we have the same situation with vocalists, so all those things we put into a Roland VP-9000. That’s our loop machine, which we can lock to MIDI. Basically, all those things people are often using Ableton for, we use the VP-9000.

“Everything else after that is synths. We have a little Mutable Instruments Shruthi, we have a Moog Minitaur as our bass - again, we have two of those that we bring, because you’ve got to have bass, just like you’ve got to have drums. Then we have a Korg Kaoss pad and a Korg Electribe EMX1. We still like the original EMX - I played with the new one but there’s something about that metallic sound to it.”

Lawrence: “It might just be a thing in our minds.”

Lenny: “It might be, but for me it feels so much more real than the other one. We have two of those -we just beat the crap out of those things - so we’ve got a back-up along with the main one for the show. Then we’ve got a Nord Micro Modular too. That’s really great because you can build your own synth sounds; it’s basically Reaktor before Reaktor existed. Right next to that is the Dave Smith Tetra and then next to that is the Dave Smith Mopho.”

Lawrence: “Dave Smith was actually at the show we played last night. We just turned around and out of nowhere it was like, ‘wow, that’s Dave Smith man’. That was cool.”

What other drum machines are you using?

Lenny: “We have an MFB 522, the little analogue one. That’s actually triggered by the EMX, so we’re layering the drums. Instead of just a straight MFB snare, we have different snares from the EMX that we’ll layer with that. It’s the same with the hi-hats and everything else; it means we have digital and analogue sounds mixed together. Then there are also drums that are coming out of the MPC1000. Those three pieces are pretty much all our drums.”

How much does that set-up change, both in the long and the short term?

Lenny: “We mix it up a lot. We started with an MPC2000, then we moved to a 2000XL, then finally the MPC1000 because it’s smaller and even more powerful. We had an Ensoniq ASR-X too. In fact, originally we didn’t have a lot of synths, we had a lot of sample playback units. Logically it made sense to us, that we could just sample the keyboards and come out and play that way, but it didn’t feel organic.”

Lawrence: “It felt locked.”

Lenny: “It felt like it didn’t breathe, so as we started getting introduced to smaller synths; we started adding those in. When the Mopho came out, that was great, because it was a small little analogue synth that almost sounds like a Prophet or something. If you’re touring something that size is so much easier. It was the same with the Nord Micro Modular - we started building things in like a Juno-106 and other things we had in the studio. That really changed how we perceived what the live show could be. We could actually have something that wasn’t static and had some life to it.

“We started changing things a lot as more gear started to become available. We started finding little instrument manufacturers like Mutable Instruments too. It’s really kind of cool, because a lot of these guys will find us; they’ll bring things down for us to try that they think will fit into our set. We have a criteria for the things we bring out on tour with us: it has to be small, it has to have a sound we want and it has to have versatility. It can’t be too heavy either.”

We’re guessing touring for many years with hardware has led to a few horror stories?

Lenny: “In the early days we thought we were being smart. We used to bring a Roland JP-8000. We used to think that because it wasn’t analogue it would be much more reliable than the Juno-106 on the road, but nah, it got all beat up.”

It’s paramount; pretty much everything we do is improvised.

Lawrence: “There was one time when we were in Paris, waiting for all our gear to come off of the carousel, and eventually we saw a knob come, then another, then our case came down all busted open. We had just flown over for two weeks’ worth of gigs and we hadn’t played one date yet. It was just pieces of gear coming round the carousel; it looked like they’d thrown the case up in the air or something. From then on we streamlined the whole thing.”

How do you go about finding new gear?

Lenny: “It’s a mixture of constant hours on the internet, going into shops, seeing things that you’ve never seen before.”

Lawrence: “I think it’s mostly you on the internet, then running out to shops or ordering stuff in.”

Lenny: “Many times, I might do a lot of research on something and it’ll look like it’s going to be a perfect piece for the show, but it’ll never even make it out of the studio. We’ve got shelves of stuff where we’ve never been able to work out how to fit it in.

"Sometimes we’ll actually go back and look at things and be like, ‘Well maybe we were trying to use that wrong, let’s try this again’. That’s happened a few times too. There’s a lot of experimenting, in all. It’s not like there’s necessarily always a need; a lot of the time I’ll start playing with something, and I’ll realise it fixes a need that we didn’t even know was there.”

What are the latest additions to the set-up?

Lenny: “We have a MeeBlip; I love that thing. I’ve actually put a bigger knob on there for the filter cutoff, so it’s more of a performance thing. It’s now got a Moog knob on there so I can really play it. Then we’ve also got a BeatStep Pro - I love that - and we have a Ketron SD2, which is basically a rompler for strings and voices and stuff. Originally we had a load of E-mu stuff in there instead, but they never made anything that small and this thing lets me pull up a whole load of sounds easily.

“Everything has a purpose in the set-up though. Take the MeeBlip, for example - we use that to layer with the Minitaur. The Minitaur provides the low-end and that’s where the real deep bass comes from, but the MeeBlip provides the top of the bassline. It means I can go in and tweak the top of the bass sound. I can crank the resonance without losing the bottom-end. It’s the same with the MFB 522; that’s layered with the EMX because I wanted the more organic feel. I like the versatility of the EMX but I wanted to bring in the thickness of the 522, and I like how that drum machine breathes.”

How important is improvisation live?

Lawrence: “It’s paramount; pretty much everything we do is improvised.”

For us music just became music, it wasn’t a genre; music was just music

Lenny: “We try to react. We try to not be too fixed in what we do. For example, we played yesterday and it was a show filled with DJs who played pretty fast and pretty hard. They stuck us right there in the middle after Blawan and our music is a whole lot more melodic than what he was playing. So we had to adapt. We normally play around 126bpm; the rest of the DJs were playing at something like 132bpm, so we had to crank the tempo up a bit. We didn’t go quite that fast but we hit maybe 129bpm, which felt comfortable for us without feeling like we’d slowed the whole night down.

"Then it was like, ‘Okay, these guys aren’t playing any melody,’ and we wanted to get that crowd -there was probably about 5,000 or so people -into somewhere more melodic. We had to basically trick them into it, so we had to try and work out what we had that could do that. I suggested a few tracks and Lawrence was like, ‘I’ll ride whatever you come up with’.

“I threw our intro on, which was like a slow 106bpm intro - we have about six or seven intros we can pick from and tweak them out as we’re going along. As we were going, after about two minutes, I had this idea. I went with a track from our new album called Pain Pressure. It basically starts with a bunch of drums and I just stripped out the melodic part of it. We just built it from there, and maybe three minutes into the mix we started adding more melodic basslines. That worked, but we had to be versatile. We couldn’t just come in playing Black Water after all that hard Techno - the place would have just cleared out.

“When I talk about being versatile, that’s what I mean. We were stripping stuff down and building it back into where we wanted it to be. By the end of the set we had them at a place where we could play Black Water. The way some people will go harder, we took it in the other direction and we went more melodic. By the time we were finished with our hour set we were properly into the melodic things, but we had to break down every song to get there.”

Lawrence: “We play off of each other a lot too. We don’t rehearse; he learns the tracks but I don’t want to hear anything until we get on stage. I just want to be able to react to it.”

Lenny: “I need to have an idea of what’s going on though. There’s too much going on onstage and I’m not comfortable unless I’ve got an idea what’s happening.”

Lawrence: “I like white knuckle rides though, I like to be on the edge!”

Did growing up in Detroit influence the mix of melodic and electronic elements that go into Octave One’s sound?

Lawrence: “That would be pretty accurate. The deep soul side we got from our parents and aunts and uncles or whatever. Even just Detroit radio; it was such an interesting melting pot with certain DJs like Mojo. He would play Rock, he would play New Wave, he’d play some deep soul stuff… I mean, he’d go from Isaac Hayes to the B52s. There was such a crazy thing going on musically.”

Lenny: “For us music just became music, it wasn’t a genre; music was just music.”

Were your whole family musical?

Lenny: “Yeah, we all played instruments. Our parents put us all in piano lessons when we were very young. People were out playing ball in the streets and we were inside having our hands smacked by rulers trying to make us get our playing right! It was pretty much just part of our development, keeping us out of trouble but also just developing us as young human beings. The thing about music is that music is good as a kid - it helps you with math, it helps you with structure and a lot of other things. That’s the reason we were put in classes, not so we’d all become professional musicians - that’s not what she wanted her boys to do by any stretch of the imagination.”

How does the way you work in the studio relate to your live shows?

Lawrence: “It varies. There’s actually five of us brothers in the studio when it comes to writing, whereas live it’s just me and [Lenny]. In the studio, one brother might come up with a bassline or some drums or whatever, but it really varies. We don’t have a set program or way of working. Until this new album, we didn’t use a lot of the gear that we use live in the studio. The studio gear is usually totally separate. Previously we were making sounds live to match what we’d created in the studio.”

Lenny: “Exactly. We bought the Minitaur because we actually have a Voyager in the studio, so we got that as it’s kind of similar but a lot smaller. We have Mopho keyboards in the studio and then the smaller Mopho modules for live. Again, we have the big Nord Modular keyboard back in the studio, so we got the Micro Modular to go with that. Generally we’re touring with smaller versions of the stuff we have in the studio. Actually, this album is the first time we’ve ever actually taken the live rig, connected it up in the studio and made music that way.”

Does software play more of a role in the studio?

Lawrence: “We use Pro Tools like a big tape machine and as a sequencer too.”

Lenny: “Our brothers use Maschines as well. They’re a bit younger, so they came in right at the tail end of when hardware was everything. They were around when hardware-digital hybrids were starting to come out, so now they totally love Maschine, which is great. What we usually do is, when they work on a track, we’ll listen to what they do and be like, ‘Okay, that’s a pretty cool keyboard sound, let me remake this on a real keyboard’. So we’ll do a lot of that. Our actual process of making music is pretty different from us playing live, but as far as how we approach music in the studio, it’s kind of the same thing.”

Want to know more? Love By Machine is out now via 430 West. For the latest news and live dates head to the official Octave One website.

I'm the Managing Editor of Music Technology at MusicRadar and former Editor-in-Chief of Future Music, Computer Music and Electronic Musician. I've been messing around with music tech in various forms for over two decades. I've also spent the last 10 years forgetting how to play guitar. Find me in the chillout room at raves complaining that it's past my bedtime.

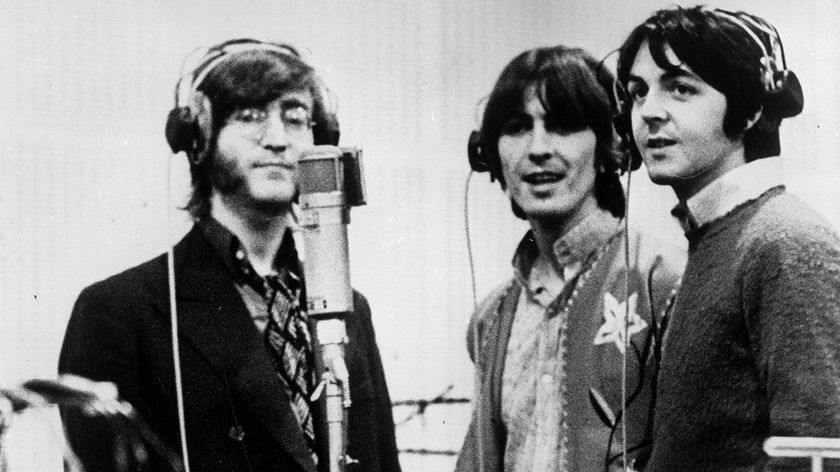

“I didn’t even realise it had synthesizer on it for decades”: This deep dive into The Beatles' Here Comes The Sun reveals 4 Moog Modular parts that we’d never even noticed before

Uli Behringer speaks out on Behringer's pricing strategy: "Our competitors say 'how much could I charge and get away with it?' We take the cost, add a small margin and that's the sale price"

![Chris Hayes [left] wears a purple checked shirt and plays his 1957 Stratocaster in the studio; Michael J. Fox tears it up onstage as Marty McFly in the 1985 blockbuster Back To The Future.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/nWZUSbFAwA6EqQdruLmXXh-840-80.jpg)