Nightmares on Wax: "I was like a mad scientist. The studio had no soundproofing, I didn’t know anything about transience and we didn’t even use a compressor, yet the tunes sounded wicked"

Due to a health scare and enforced DJing sojourn, Nightmares on Wax’s George Evelyn was forced to totally re-evaluate his life and craft. Danny Turner learns more

When George Evelyn released Nightmares on Wax’s debut album A Word of Science; The First and Final chapter on Warp Records in 1991, he could not have envisaged that he’d still be signed to the label 30 years later.

In between, he’s been a pioneering force on the downtempo scene, shaping, defining and blending elements of electronica, jazz, hip-hop, dub, funk, soul and techno on classic albums such as Smokers Delight, Carboot Soul and In a Space Outta Sound.

However, after decades of DJing and touring, the pandemic finally gave Evelyn space to pause and re-evaluate his history, while a health scare simultaneously forced him to seriously reflect on his next step.

Questioning whether this might be his last album, Shout Out! To Freedom… was infused with an added sense of urgency. The result is clearly Nightmares on Wax’s most personal and expansive album to date, forged through collaboration and a renewed perception of his craft.

How do you feel about being officially Warp Record’s longest serving signing?

“Being a fan of the label, it’s amazing to watch how it’s evolved and grown. At the beginning we were going around to clubs trying out test pressings and I often wonder how everything’s gone from that to this.

"We’ve grown up together and it’s been a bit of a fairytale. I don’t think any of us envisaged Nightmares on Wax still being on the label, but I definitely accept my importance to Warp and the label’s importance to me.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

30 years into your career, it was surprising to hear you say that you feel you’ve been set free and become who you really are. What provoked that realisation?

“As you evolve as an artist you become a lot more observant about life. Along the way, you can become a little bit too analytical about what you’re doing and that can imprison you, especially coming from the angle of being a perfectionist.

"Part of being a creative and mastering your craft is having peaks and troughs and going down rabbit holes, but at some point you have a sense of realisation and end up wondering what made your magic moments so good. I thought about what made writing certain songs so easy and why all the others felt like puzzles.

"Throughout lockdown I had the time and space to analyse all of that and what I learnt was to just get out of the way and let creativity happen. The music doesn’t have to be anything, so just make it and stop worrying about whether it has to fit anywhere. I also asked myself the biggest question; is it any good?”

I’ve realised that when you acquire knowledge and gear, you’re literally opening a can of worms

How do you go about getting an answer to a question that’s so subjective?

“I’ve been in situations where I’ve worked on projects, really gone to town on them and right at the end that question’s come into my head – and it’s really uncomfortable.

"What I feel I’ve learned now is that the creativity was always there from the beginning but without the acquired knowledge. When you acquire a certain amount of knowledge it has an effect on you, which can be good or bad. It’s no longer about having all these tools and needing to use them, you just need to remember why you love making music, be a kid again, have fun and just play.

"As long as you’re creating, you’re mastering your craft, and all that questioning set me free in some sense and I found that really empowering.”

Would you say that you’ve had to go through something of a process of unlearning?

“Totally. Like I said at the beginning, it’s learning to get out of the way. In simple terms, if you go to play on a keyboard, don’t think about what you’re going to play, just play it. Especially as I come from a sampling background, which was all about experimentation, manipulation and imagining what I could do with a sound.

"Back in the day I was like a mad scientist, the studio had no soundproofing, I didn’t know anything about transience and we didn’t even use a compressor, yet the tunes sounded wicked, so how come I suddenly found myself going through a minefield to get a tune to sound boss?

"I’ve realised that when you acquire knowledge and gear, you’re literally opening a can of worms. So I went down that path, but now I’ve come home to the bare basics.”

Is that also a commentary on the DJ lifestyle and how it’s so frantic that you rarely have the time to evaluate what you’re doing?

“Once you start releasing albums, you start touring and once you start touring you end up in a cycle of finishing a tour, recovering from that, doing a DJ tour, making a compilation and starting the next album.

"Once I stopped still and realised I wasn’t getting on a plane or didn’t have to be anywhere, I had this space that enabled me to say, actually, I don’t need all this gear and I can make music without having anything on my mind about where I’ve got to be.

"After doing four DJ sets a week in four different countries, that puts you in a totally different mindset. I can only speak for myself, but when you’re in that routine, there’s no way you can be fully invested in what you’re writing.

"That’s why I’m really proud of this album, because I know the honesty, balance and emotional connection is 100% there. I’m not saying I’m never going to DJ again, but this is where I want to be and I have to be more protective of my time now.”

We understand that you had a health scare too?

“That happened in February this year when I had an operation for a suspected brain tumour. Building up to that, I’d already written a section of the album but was still waiting for all the pieces to fall together.

"What with the pandemic – the sense of everyone feeling trapped and being set free from my touring life – I found my family again, realised that I’d never really lived in my house and started to feel like the stuff I was writing were actually cries of freedom. When the health scare happened, it was another thing I wanted to be free of.”

Presumably that added an extra layer of reflection and urgency for you?

“The health scare gave me a massive rain check on what I’m doing and how time is the only currency you have, so it inspired me to do more. I didn’t want to think of the worst case scenario, but I’d be sat in the studio and random thoughts would come into my head, like have you sorted your family out and could this be the last record you’re ever going to make?

The influence of touring and using live musicians totally opened things up for me because I could actually sample them

"A voice inside of me told me not to resist that, so I thought about how I’d feel if this really was the last record I was ever going to make and, if so, what would I make? It woke something up in me and I thought I’m going to go even deeper now and maybe create some healing out of this too.

"From that perspective, the album is dedicated to everybody who wants to be free of something. Thankfully, I’m still here today and don’t really have an issue anymore, so I’m very grateful for that, but I’m also grateful for having had the experience.”

With Shout Out! To Freedom… would you say that you’ve returned to the soulful dub/jazz sound you were originally associated with, albeit adding all those years of experience you mentioned?

“I would say that, but I’ve also got the access that I never had to other musicians. I feel like I’m at a stage in my journey where I can call upon the really high-level collaborators that I want to play on my records, whether that’s big classical composers like Steven Bentley-Klein, saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings or vocalist Greentea Peng.

"It’s taken me this long to do what I’ve always wanted to do. It’s not that I’ve been held back from doing that, but I needed the experience, the time and the journey, and I can’t go into a song now without thinking about the production being on a certain level.

"You can see from my back catalogue how orchestration has been a massive attraction for me, but sonically I feel I can achieve that on a much bigger level now, and fully realise what I’ve been suggesting all along.”

You’re not new to collaboration though?

“I’ve always collaborated with people. Robin Taylor-Firth has played keys with me for about 18 years and I’ve done string arrangement on tracks like Les Nuits. When I wrote Carboot Soul I remember feeling an overhang from Smokers Delight, which was a concept album.

"I wanted to do something that was completely different, which was a massive challenge, so I went to town on that record to break away from Smokers Delight. The influence of touring and using live musicians totally opened things up for me because I could actually sample them.

"So collaboration has always been there, but whereas I collaborated with people within my vicinity, I tend to think more broadly and on a global level now. Through that, I’ve found quite a lot of serendipity.”

With collaboration, do you have a good idea of the result you want to achieve or do you prefer leaving things open to improvisation?

“It’s different with each person. Haile Supreme was an artist that my friend’s wife found on Spotify. They sent me a song called Danjahrous and I thought, I’ve got to get in touch with this guy.

It doesn’t matter what style of music I make, whether it’s a house track or something acoustic, the mentality is to deconstruct and manipulate combined elements

"It turned out he was a fan of mine and lived in Brooklyn, and I was heading there in two weeks’ time, so we hung out and it was like we’d been friends forever. He flew to Ibiza the following month and we wrote eight songs in five days and another bunch in November 2019.”

The song 3D Warrior is a fine example of lots of collaborators coming together, but then never actually meeting…

“To give you some history on that, basically I’ll go digging for records from all over the world and at some point sit in my studio and just loop stuff all day and jot down notes when I’m travelling.

"In May 2019, my jazz drummer Wolfgang Haffner came over from Germany and spent a day freestyling drums over my loops, leaving me with loads of sketches that I could write songs to or give to my keyboard player.

"For 3D Warrior, I’d been recording with Wolfie all day and he was sat at his drum kit making tribal beats and lost himself on a loop for about 11 minutes, which I thought was really something else. Then in October, I went to Leeds to record some keys with JD73 and bass with Alex Beans and we pulled up Wolfie’s track and came up with this mystic eastern keyboard rhythm.

Now when I listen back to the track, I can’t believe it was made in four different places. It’s so against how I would normally make music and none of the musicians had even met each other

"Then in November, we were in the studio with Haile Supreme and he started talking about how we all live in this 3D reality and everybody needs to be a warrior to exist in this world, and that’s where the theme came from.”

Who added the saxophone arrangement?

“The Shabaka Hutchings opportunity came in December. I told him I had these three different scenarios, put a rough arrangement together, sent it to him to perform his magic and then gave everything to Haile to squeeze into a session that he was already working on for me.

"The recording came through on the morning of my 50th birthday while I was sat on the beach in the Maldives and I couldn’t wait to work on it – I just had so much gold to work with.

"Now when I listen back to the track, I can’t believe it was made in four different places. It’s so against how I would normally make music and none of the musicians had even met each other.”

Having worked with samples for so long, do you think that experience helped you to pull all those disparate sessions together and create the track?

“I’ve obviously tried working with different producers and know that my process is very different because I don’t turn up with something that’s finished. All of my collaborators go on a journey with me and don’t know where I’m going. I just know what I need, and when I’ve got enough material I’ll go away and do the alchemy.

"There’s no denying that my approach to making music comes from hip-hop. It doesn’t matter what style of music I make, whether it’s a house track or something acoustic, the mentality is to deconstruct and manipulate combined elements.”

Have your ideas about sampling changed in this process?

“To me, sampling is more about what I think I can hear than what I can hear. I’ll get a pile of obscure shit from Malaysia or India, get stoned, spend a day throwing records on, record the first thing that’s catching me and at some point later something will pop out. Sometimes I’ll chop a sample up, build the music around it with live musicians and remove the sample, so I’ve only used it to inspire me.

All albums are a mirror; you remember where you were at certain points in your life and how you were feeling

"On a track like Up To Us, it’s just a straight two-bar guitar sample, but the original sounded so hypnotic and there was a sense of suspense because of the crackle and sound of the cabinet it was recorded in. I knew it wouldn’t sound the same if I tried to recreate it. In that case, I used the sample and brought in orchestration and drums to make something else.”

How did you discover Greentea Peng, and was her vocal contribution on Wikid Satellites recorded remotely too?

“I’m a music fan first, then a DJ, then a producer. I’m still listening to people because I want to be inspired, and when I heard Greentea I thought she’s got shit to say. The colour in her voice is beautiful, but it’s also about the content and feeling.

"I sent her a folder of stuff and we did a bit of back and forth, then it went from text messages to voice notes. We went on like that for eight months before we even spoke to each other.”

Some of those voice notes feature on the track GTP Call?

“She called me a cheeky bastard because she didn’t even know that was on there until a month ago, but it’s good to capture all of that because it’s real. All albums are a mirror; you remember where you were at certain points in your life and how you were feeling.

"When I’m writing music in album mode, certain feelings and moments become familiar and that’s when you know you’re on the right path. Everything starts gravitating towards the centre, the things you were really buzzing about get pushed to one side and you suddenly have this musical spine.”

How have you found the process of piecing together other musicians’ live recordings?

“The only actual live playing I wasn’t present for was the wind and string instruments. I trust the people I’m working with and when I set up a session I tend to only use one microphone anyway, which takes me to a certain stage before I lose myself down a rabbit hole trying to get the right sounds and textures.

I tend to mix while I’m writing because it needs to sound like I’m imagining it

"I mixed some of the album myself and got the rest to a certain level before giving it to Philip Harris to mix. I went so deep with the record that I thought it would be good to get a fresh set of ears to take it to another plane, so I’ve got to credit Philip for that.”

The tracks are quite sparse-sounding but you seem very adept at colouring the sound to fill up the mix…

“As somebody said to me years ago, space is the place – how much can you create? When I think about all my favourite productions or the songs I really love, they’re really simple. I’m still working on that, but then I’m always learning different tricks. In the early days I’d learn how to do drum fills, but then I’d put a drum fill on every track until I realised I didn’t have to keep on doing that [laughs].

"It’s the same with writing songs, how can you say a lot by saying little or how can a mid-section get from one place to another without too much going on yet still feeling like it’s progressing. So I’m very aware of the question I’m asking and I definitely spend more time learning how to take things away, but that’s a journey in itself.”

Do you rely on specific tools to plump/colour the sound?

“In lockdown, I sat in my studio, looked around and decided what I no longer needed. I felt I needed to do some research and see what’s out there, so I got rid of my TLA Audio analogue desk, which I’d had for 15 years, and went for a Softube Console 1 Fader setup, which gives me British Class A and SSL 9000 definition.

"Then I looked at my AC converters and called on a good friend who’s got a mastering studio out here and he introduced me to Burl Audio equipment, which has been a massive help.

"Before that, I’d used UAD and MOTU, but I struggled to get something to sound ‘ten past two’ and the Burl Audio B2 Bomber has really made the difference alongside the B80 Mothership AD/DA interface which has got the in/outs, mic pres and an amazing BNC clock.

"I thought that upgrading everything would sound better, but for depth, transience, space and things staying where I put them, it’s been a game changer, although I’ve still got the UAD Apollo 8 for my DSP, plugins and stuff.”

And what point in the writing process will you implement these tools?

“I tend to mix while I’m writing because it needs to sound like I’m imagining it. I know that some people just write stuff and mix afterwards, but I find that irritating and this technology has shifted things for me because everything sounds exactly how I want it to now.

It’s very hard to find someone at these companies to talk to these days – and I’m not talking about sales reps, but people who actually use the gear and are passionate about it

"At the end of the chain I’ve got the Tegeler Audio Crème unit for EQ/compression and that combination of outboard glues everything together and has speeded everything up for me. What I like about Burl Audio and Tegeler is that you can ring up the guys who built and made this shit and actually talk to them about the different ways to saturate, route and use their mic pres.

"It’s very hard to find someone at these companies to talk to these days – and I’m not talking about sales reps, but people who actually use the gear and are passionate about it.”

Do you have any other hands-on hardware?

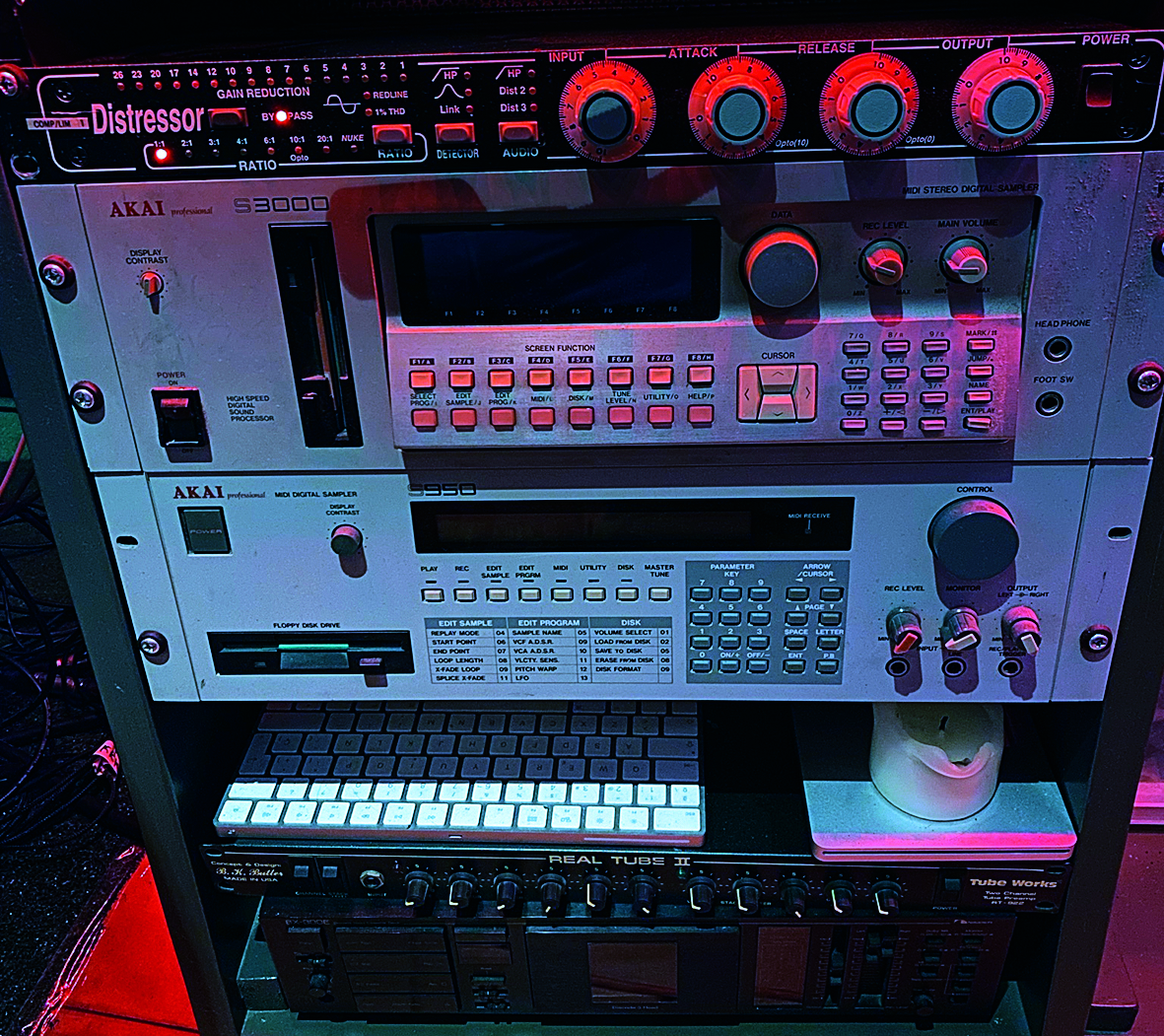

“I’ve got the Roland Jupiter-Xm, which is a really cool keyboard that still has the Juno-106 modules, my 808, which is about to go into service, and a couple of little toys like the Moog Minitaur, which is amazing for bass sounds. I’ve also just invested in a Behringer Model D and I still use my Akai S3000 and NI’s Maschine Studio, although I’m kind of slipping away from that a little.”

So you’re still using vintage samplers?

“When I started using samplers it was literally the Atari ST, a mother keyboard and an Akai S950. We’d buy boxes of floppy disk sounds, so that and sampling was our library back then, but I still like the writing process of using a sampler and a keyboard.

"On the software side, I still use Logic and find that Serato Sample is really good. Loopcloud is also great if I’ve got a vocalist in here and need to move quickly and pull up a beat. Softube software is really good, especially Parallels for synth soundscapes and their bass plugin Monoment Bass.”

If it ain't broke... 5 artists making music with old-school technology

This is actually your second studio in Ibiza?

“I used to live in a 17th century farmhouse, but seven or eight years ago I moved to a villa on the top of a mountain. This is the first ever studio where the room was built for me bespoke. It was an empty shell when I moved in and the way it’s built now, there’s a mini apartment here for musicians to stay in. It’s definitely the best studio I’ve ever had – it’s called the Othership, because it’s where the other shit happens!”

Nightmares on Wax’s Shout Out! To Freedom... is out now on Warp Records.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.