Nick Johnston talks technique, gear, Guthrie and Gilbert

The Canadian instrumentalist on his 'atomic rock'

Introduction

If you think instrumental guitar is mindless widdling, then you haven’t heard genre-blurring visionary Nick Johnston.

As the Canadian virtuoso hits Birmingham for an in-store clinic, he tells us about “heavy” bluesmen, watching Jeff Beck fall over and his lifelong fear of guitar shops.

You can mention him in the same breath as Vai and Satriani without being laughed out of the room

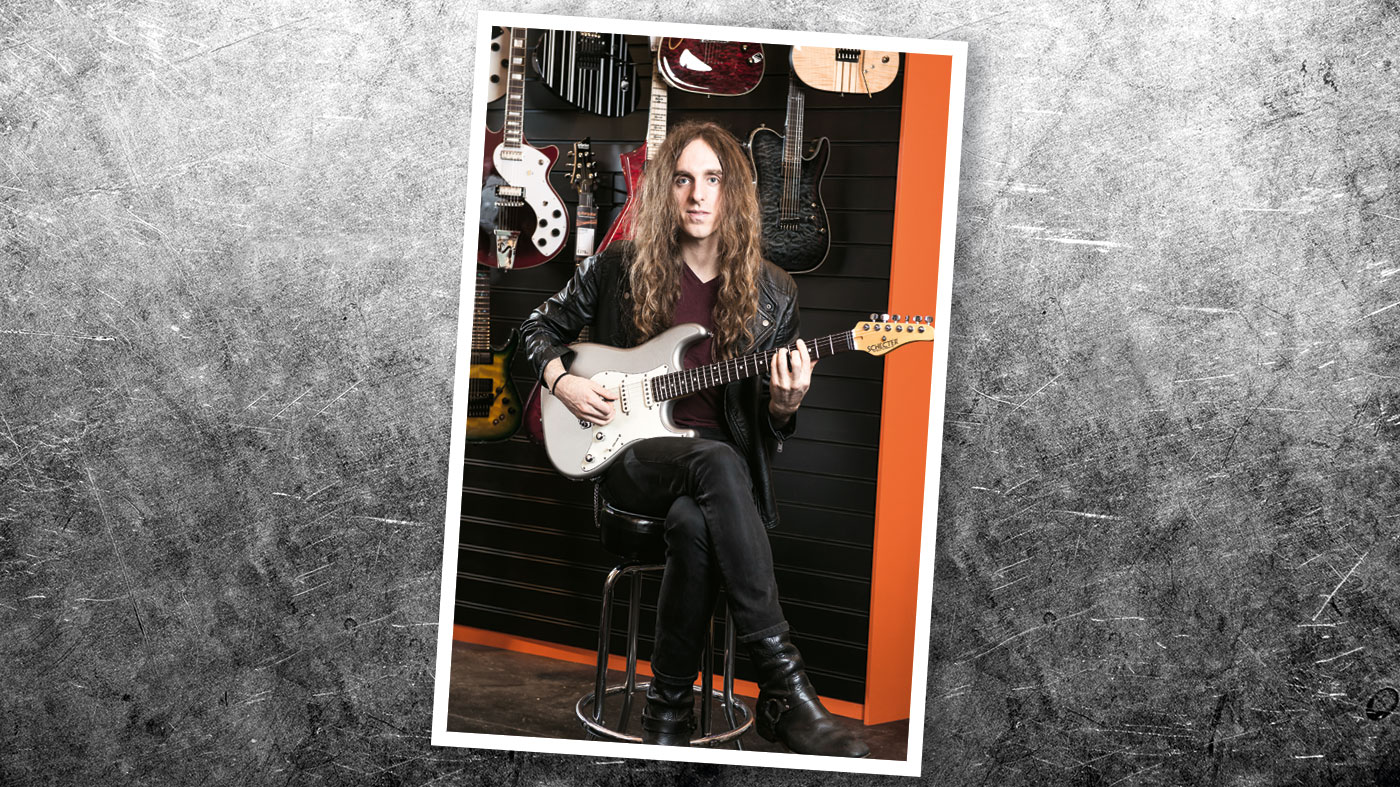

You meet all sorts of people at Birmingham’s GuitarGuitar. One day it might be Paul Reed Smith fielding an in-store Q&A. The next day, it could be Mark Tremonti picking up patch cables.

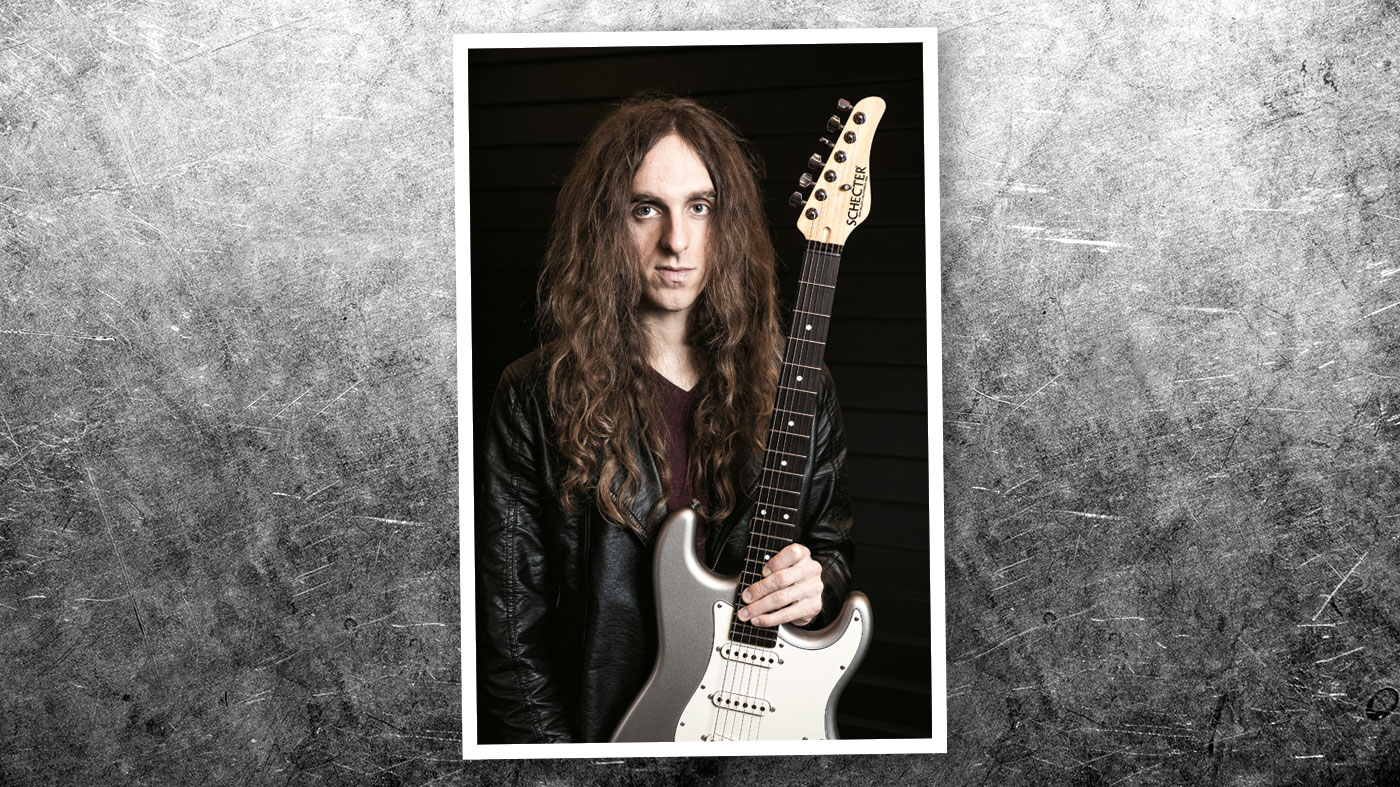

On this particular morning, we find a wide-eyed, leather-jacketed 20-something walking the aisles. That’ll be Canadian hot-tip Nick Johnston who’s in town for tonight’s clinic, at which his growing army of disciples will hope to catch a little bit of mojo as it flies off his fingers.

We have much to learn from Johnston. His debut album, 2011’s Public Display Of Infection, debuted a blazing instrumental style that came on like the bastard son of blues. His second, 2013’s In A Locked Room On The Moon, pushed the envelope with world-music flavours, and underlined his growing status with cameos by Paul Gilbert and Guthrie Govan. His third, 2014’s Atomic Mind, painted sonic pictures so vivid that you can mention him in the same breath as Vai and Satriani without being laughed out of the room.

Instrumental guitarists can be an insular bunch. Thankfully, for an artist who speaks solely through his Schechter signature model on record, it turns out that Johnston has plenty to say…

Don't Miss

Exclusive: Watch Nick Johnston's Making of Remarkably Human documentary

Atomic rock

Do you like being in guitar shops?

“It’s funny, but when I started playing at 14, I always had this irrational fear of guitar shops. You’d walk in and there’s the guy behind the counter with tattoos. Then you see all these guitars, and you want to try one, but then you gotta plug into an amp and people will hear you. On some level, there’s always that little kid thinking, ‘Oh shit, I’m going into a guitar shop…’”

Would it be a shame if people started only buying guitars online, though?

You can’t know anything about a guitar until you’ve played it. It’s as simple as that

“Yeah, it would. You can’t know anything about a guitar until you’ve played it. It’s as simple as that. There’s the whole internet culture, people on forums talking about gear, but you’ve gotta go and put your hands on the instrument.”

On Facebook, you describe your genre as “atomic rock”…

“It’s like rock, but it’s supercharged, really eclectic with a lot going on. That word ‘atomic’ just felt right. I always loved that kinda 50s B-movie and comic-book stuff. When I was writing my second record, In A Locked Room On The Moon, a lot of that seeped into my psyche. I think you can hear it, especially on songs such as The Evil Stepsister or The Pickpocket’s Remorse.”

What advice would you give someone who wants to write instrumentals?

“I get asked that at clinics and the answer, for me, is to think about melody and arrangement. What do you have to say? Can you hum the melody? 90 per cent of the time, I just sit there with an acoustic and sing the melody. I could play all this music just with a singer and an acoustic guitar.”

Because a lot of instrumental guys just tend to widdle…

[Widdling shred players?] I don’t want to call that an escape route, but I think it’s a security blanket

“And, honestly, that’s an easier thing to do. I don’t want to call that an escape route, but I think it’s a security blanket. It’s like, ‘I can just have three chords, then arpeggios and tapping.’ There’s a huge market for it, and there are bands that do it way better than I’ll ever be able to. But… I don’t care. I love melody.”

What makes good guitar playing for you?

“The first thing that attracts me to a player is the touch. It’s their vibrato, the sound of their hands. It’s not about how much technique they’ve developed, or what they can do with the guitar. It’s more about notes, pitch, harmony, songwriting, and melody.

“It’s the stuff that you don’t develop in the first 10 years - or even 20 years - of playing guitar. It’s the stuff that takes a lifetime. I think patience is the name of the game with guitar playing, unfortunately; because everyone wants to be good now, especially with the internet.”

Having said that, your stuff is actually pretty damn technical…

“The technical stuff, it’s fun for me. It’s so much fun to slip something like that in. I don’t have anything to prove. Straight up, I just enjoy doing it. It’s a nice accompaniment to my range, because my melodies are usually really simple and the songs themselves are like a pop structure. When it’s time to solo, I’m gonna go for it.”

Signature sounds

Do you have any signature techniques?

“There’s some legato lines, the hybrid picking stuff, some of the bending stuff. I watch it back and it’s like, ‘Oh shit, I’m doing that again!’ I like to take a note that’s not in key, just so there’s a bit of tension, then bend it up. Like, I’ll take the b5, bend it to [the] 5.

“Basically, I like to take stuff that’s not in [key], and bend it in. With legato, I like string skipping stuff. I like chromatics. I try to blend different minor scales: natural minor, harmonic minor, melodic minor. I do a lot of descending stuff.

As soon as I started playing with other people, I realised that almost everything I was doing didn’t work

“I like stuff with 9ths. I like augmented chords and dominant chords, because you can do so much over them: minor, Mixolydian, Phrygian Dominant. I do a lot of stuff with the volume knob and pickup slider - it’s almost like the guts of the guitar is its own instrument.”

How do you think your playing has evolved?

“You’re always trying to eliminate stuff you don’t need any more. When I was a teenager, I was far more technical in terms of note count, but as soon as I started playing with other people, I realised that almost everything I was doing didn’t work. They’d be like, ‘We’re playing this groove in this key. Now take a solo.’ And I was like, ‘I can’t, I don’t know how to play in that key. I can’t play with that note count. I can’t groove with that feel.’ You realise what’s important at the core of your playing.”

You started as a Strat man. What made you switch to Schecter?

“I was using the Fender Custom Deluxe line for 10 years, and I was like, ‘There’s nothing better than this.’ Then a friend introduced me to the VP of Schecter. He asked me, ‘What would you try if you were gonna use Schecter?’ And I said, ‘Well, what’s your version of the guitar I’m using now?’ Then a Traditional model showed up at the house. Within an hour, I was like, ‘Here we go.’ It’s so cleanly built. Such a strong instrument. With travelling, that’s invaluable.”

How did your signature model (pictured) evolve from the Traditional?

After a band played before me with four pedalboards and rackmount shit, I’d just go up and put the lead into the amp

“Well, we changed the pickups. The single coil that the Traditional comes with, it’s a little flatter-sounding. For a long time, I’ve been using the Duncan Antiquity Texas Hots. They have more midrange. Some people hate that 60 cycle hum, but I like it because it sounds real. It’s got a 14-inch radius - very flat - and the neck is wider, because I like to do minor 3rd and major 3rd bending, so I need that extra room.”

You’re also using your preferred Friedman BE-100 at tonight’s clinic…

“It’s just got that Plexi brown sound. It’s really warm, rich, gorgeous - you can’t get a bad sound out of it, basically. For me, it’s the perfect amp at this point. There’s a new reverb pedal coming out from MXR, so I’m gonna put that in the effects loop, because the Friedman doesn’t have a reverb channel. But that’s it. I just plug straight into the amp, usually.”

You don’t use pedals live either, do you?

“Again, it’s the amp: you can get that really rich distortion. And I use my volume knob, so if I have the amp set high, I’ll usually roll it back to get a cleaner sound. Part of that, I guess, was born out of [the fact that] I just didn’t want to carry pedals, and I didn’t have money for extra gear.

“But the other side was, my favourite players didn’t really use pedals. Like, Eddie Van Halen, Jeff Beck, Stevie Ray Vaughan. It was a pretty simple setup they had and I loved that idea. It was pretty rock ’n’ roll. After a band played before me with four pedalboards and rackmount shit, I’d just go up and put the lead into the amp. And sometimes you suck. But sometimes you’re really on.”

A new blues

Where do you stand on the subject of blues guitar. Are you a fan?

“I love it. A lot of non-blues-guitarists think, ‘Oh, blues is simple.’ But it’s actually incredibly complex, when you delve into that world. On the surface, it’s such a simple thing, y’know - a five-note pentatonic scale.

“But literally your entire life will be spent on the phrasing, blending it with other scales and intervals, the tension and release. It doesn’t just have to be ‘I-IV-V’ either. Like, jazz-blues: there are all sorts of substitutions, tritones, melodic minor, harmonic minor.

There are a lot of great blues players, but SRV’s technique, pitch, control: it was on a different level

“I get terrified by blues, because there’s so much you can be doing with it. A good blues player, you can tell - it’s like, ‘This guy is heavy.’ I love Michael Landau. Jeff Beck. Larry Carlton. Stevie Ray Vaughan…”

Do you remember when you first heard SRV? What were your initial thoughts?

“Yeah, and it actually happened at a point when I used to think, ‘Why are people playing blues?’ Then I heard him and it was like, ‘OK, I get it now.’ There are a lot of great blues players, but Stevie’s technique, pitch, control: it was on a different level. He reinvigorated it. His soloing. His intensity. The fact he used those incredibly heavy strings. You hear so much aggression in his playing.

“One of the first things I heard was Tightrope, then Scuttle Buttin’. From there, I heard Scott Henderson, and it was like, ‘Holy crap, I don’t know anything.’ But Jeff Beck is my favourite player, far and away.”

He can be erratic, though…

Eddie Van Halen always had a gorgeous vibrato. He’s kind of a blues player, too, just more unorthodox

“That’s the sign of a genius. It’s like, he’s either exploding or he’s at a complete low. When I saw him, it was the tour for Emotion & Commotion and he had the orchestra with him. It was the touch. It was the tone. It was funny: he tripped on stage, completely fell over, and he was still soloing.”

What are the core techniques for playing good blues?

“I think vibrato. For me, it was the most difficult thing to develop. I always just tried to copy my favourite players. Y’know, Beck’s vibrato. Eddie Van Halen always had a gorgeous vibrato. He’s kind of a blues player, too, just more unorthodox. Even a guy like Dimebag Darrell was extremely bluesy - unorthodox as well, but he still had this foot-dragging blues feel. I’d listen to these guys and try to copy them.

“Eventually, you’ve heard so much stuff that you kinda come up with your own version. It’s important to learn clichéd blues licks, y’know, Johnny B Goode or those Clapton licks. Then you use those like checkpoints, and it’s what you do around that.”

Looking forward

Do you think you can hear a blues influence in your material?

“Definitely. The approach to the songwriting, soloing and improvising - it’s undeniable. Because rock ’n’ roll is definitely my upbringing, and you are what you eat. If you listen to that stuff, it’s gonna come out in your playing.”

At the same time, you’re not afraid to throw in a number like Sandmonster…

You can’t impress a guy like Guthrie Govan. He can do everything. He will continue to be better than you

“I played in an acoustic trio for years and we did a lot of world music. I got really into harmony, like, ‘Why does something sound bluesy or Latin or Brazilian?’ The music on that second album, it’s all pretty much from that world music approach.

“On The Pickpocket’s Remorse, I tried to do some French stuff, with the tritones and going to the minor on the IV chord. Songs like Evil Stepsister are very tango-influenced. Sandmonster is Latin-based.”

You also collaborated with Paul Gilbert and Guthrie Govan on that album…

“I’d written a song called Trick Question, and it was very simple: E minor pentatonic over an E chord, and the chorus is very Beatles-esque. So, the fact that Paul was willing to play on it, just because he liked the melody, basically reaffirmed the whole technique thing for me.

“Again, you can’t impress a guy like Guthrie. You just can’t. He can do everything. He will continue to be better than you. But I sent him the song and he was like, ‘Ah, I like the melodies.’ For me, it was fulfilling a personal dream. I was in high school when I heard Guthrie, and I’ve been listening to Paul since I was 13.”

What can we expect from the new album?

“It doesn’t have guest solos this time. I kinda want to get away from that. It’s actually the first album where every song is in one style. It’s a bit more like 70s progressive music. The songs are longer, the material is more epic, very film score and classical-influenced.”

Finally, if you could steal any guitar from this shop, what would it be?

[Points at James Trussart models] “I like the look of those rustic guitars over there. They look like biker guitars. But these days, I’m totally faithful to my Schecter. I walk into a guitar shop and it’s like, ‘Next…!’”

Don't Miss

Exclusive: Watch Nick Johnston's Making of Remarkably Human documentary