Nik Colk Void: "I couldn’t make a banging dance album or an experimental album – it had to be between the two"

Known for her improvised approach to modular systems, voice and guitar, Nik Colk Void talks to Danny Turner about her long-awaited debut album

After fronting the indie-rock band KaitO in her formative years, an unfulfilled Nik Colk Void returned to the world of visual arts before deconstructing her approach to studio and live performance and joining post-industrial duo Factory Floor.

While performing on-stage in 2011, Void was spotted by former Throbbing Gristle members Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti, resulting in an invitation to play live and record with the duo under the pseudonym Carter Tutti Void.

Despite recording three albums as CTV and nine in total with various other collaborators, Void remained reticent to create solo work until convinced by the late Editions Mego founder Peter Rehberg.

Void therefore set about reformulating her live and studio-based modular synth patches as a basis for the creation of her debut LP Bucked Up Space – a fearlessly unsettling album that encourages the listener to absorb its visceral tones and textures in their rawest form.

Did you have reservations about coming into an industrial scene that’s always had a very niche audience?

“I’m a fan of sound in general and more attracted to the tonality, textures and attitude of industrial music. I grew up in the middle of nowhere and once I could travel to London and hear music at massively loud volumes that had more of an impact on me than vocals and lyrics. My career has also been determined by the type of tools I use.

Putting the guitar on a table rather than holding it made a big difference in terms of having a new point of entry to the instrument

“With the guitar, I lost interest in making riff music and preferred to hit it with drum sticks or use extended techniques to create peculiar, resonating feedback. With industrial and electronic music, it’s more about the impact of the sound and how it resonates in physical form.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Having said that, you were part of an indie punk band called KaitO, which does indicate you explored the singer/songwriter route?

“Dammit, how did you find that out [laughs]? I never thought I’d get anywhere playing music or art and fell into the band idea because it was a vehicle to get myself out and about travelling. Music used to be a massive part of my social environment, so I started the band and we got picked up by a Californian label called Devil in the Woods who invited us to go over and tour. It was an incredible time, but I was just going along for the ride to be honest.”

Were you making music independently to that?

“I just craved being around other creative people, but everything has its time and after six years I moved to London and ended up working as a sculpture technician. Guitar music was no longer for me and I didn’t like the attention of fronting a band. It wasn’t until I saw Gabriel Gurnsey and Dominic Butler of Factory Floor playing live in East London that I fell back into music again.”

For you, the guitar had become a symbolic instrument. How did you attempt to readapt your use of it?

“When you work with other people it’s easy to play it safe, so having a break allowed me the space to forget what I’d learned and approach guitar playing from a different angle. I decided that if I wanted to go back into music I’d do it my way and everything became about how I could use a sound and play it in on my terms as opposed to how I’d been taught. Putting the guitar on a table rather than holding it made a big difference in terms of having a new point of entry to the instrument.”

Did working with Factory Floor open you up to electronic music and the possibilities inherent in that realm?

“Not really, Paul Smith of Blast First records was my mentor on that front. Factory Floor was a meeting of minds. We weren’t just using guitar pedals but guitar sequencers and small hand synths and adapting them to give us original sounds straight off the bat. Once again I found myself falling into the lead vocalist space, which I wasn’t really into, so I re-evaluated my approach to vocals too. We manipulated noise and vocals and turned them into heavily processed samples, concentrating more on sound rather than the constructed tracks that Dom and Gabe had been playing.”

You seem to want to distance yourself from having a persona. Does that play out in your music?

“I gave up thinking about how I fit into the industry quite a long time ago and I’ve always worked in visual arts so there’s been a running theme throughout my career based on a play on words. The starting point is usually a terminology, like the album title Bucked Up Space, and I move on from there. Together, it all feels like one form, but I also have a natural inquisitiveness about sound. It’s all about pushing the instruments to see how far I can take them, which is why being introduced to modular synthesis has been such a great experience.”

How did your collaboration with ex-Throbbing Gristle members Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti manifest?

“Factory Floor had a residency at the ICA and Chris and Cosey came to one of the shows. Paul Smith was there too, and he managed Throbbing Gristle at the time. I think Chris and Cosey saw something in my on-stage approach that was a little similar to theirs, so they asked if I’d like to collaborate with them for a show at the Roundhouse for Mute Short Circuit. I took some gear on a train to their place in Norfolk with no idea of how things would pan out, but they were super cool so I went back to their studio and they set up a table for me to lay my gear out on.

“As soon as we got plugged in, everything seemed to happen naturally. It was great to play with another guitarist who wasn’t using the instrument in a traditional sense but was more interested in sound, resonance, feedback and noise. When we played together at the Roundhouse I was nervous because we were in front of a TG-dedicated crowd, but they welcomed me in and from then it was a no-brainer to continue our association.”

As part of Carter Tutti Void you presumably had complete freedom to improvise, both on stage and on record?

“For the live shows we had a loose structure created in the studio and mainly directed by the tools we were using to appropriate different tracks. I was holding the guitar in the traditional way on-stage but using bow and sticks. With Factory Floor we were more competitive in terms of who could play the boldest noise, but with CTV Chris presented the underlying rhythms, which had an instantaneous groove, and Cosey and I responded in a way that was very natural and improvised. We’ve made three albums together, two studio-based, but Chris and Cosey have quite a strict agenda where they prefer projects to have a limited lifespan.”

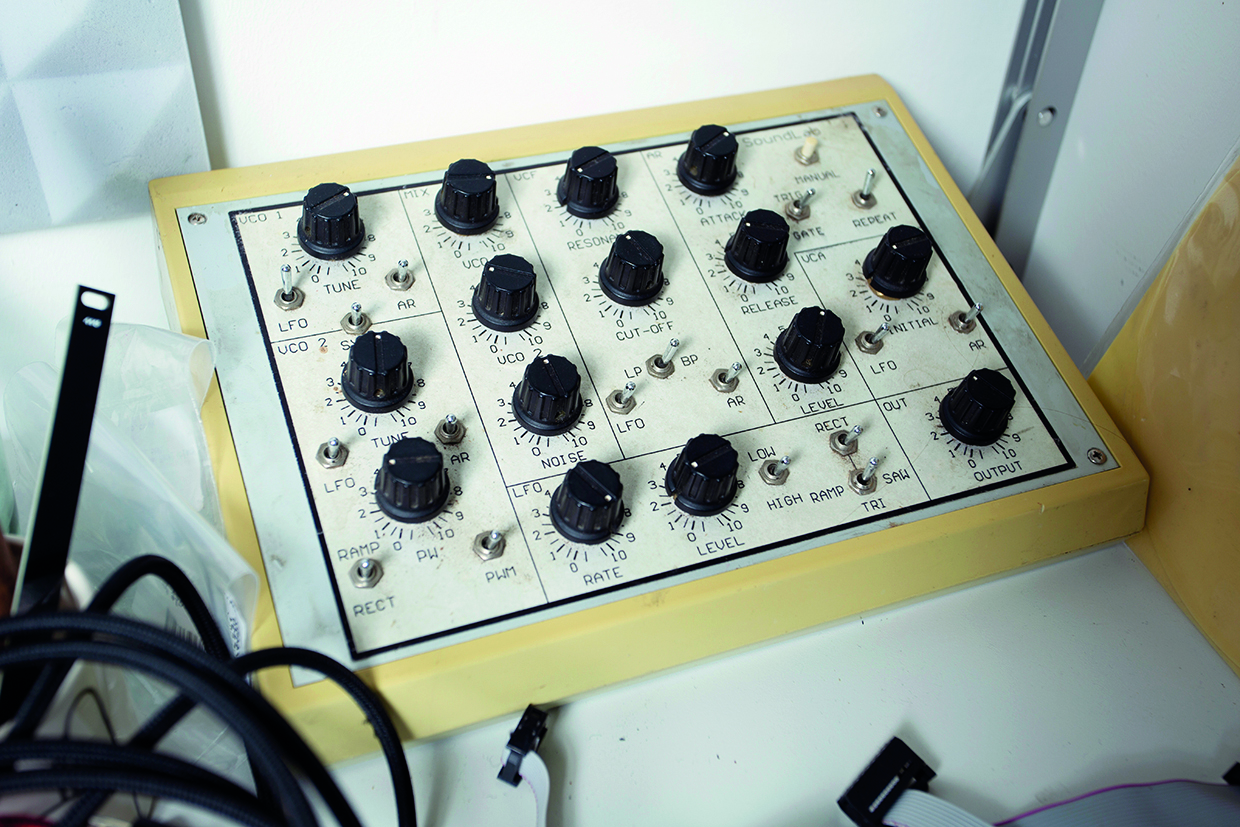

Was it Chris who introduced you to the world of modular?

“Definitely, when you walk into his studio it’s just a wall of modular. I was gravitating towards the modular world anyway because I wanted to experiment more with noise and sound and Dom wanted to take a break from Factory Floor so I had a big hole to fill. Seeing Chris on numerous occasions meant he could give me lots of technical advice, but there’s loads of help out there from companies who distribute modular synths. That’s not something I encounter when going into a guitar shop, which is usually quite daunting and uncomfortable.”

Your debut album has been a long time coming. Why was now the right time to introduce yourself as a solo artist?

“Collaborating with other people has always been the main agenda. I’d done a few shows but didn’t feel I’d reached a level of maturity where I had something to say as a solo artist.

I couldn’t make a banging dance album or an experimental album – it had to be between the two

“I wanted to make sure I was ready to release something that I could be proud of and represented where I was as a musician, so when Peter Rehberg of Editions Mego asked me if I wanted to make a solo record it stopped me in my tracks. The great thing about Editions Mego is that they didn’t put any time constraints on me, but the devastating part is that Peter passed away and didn’t get to hear the album.”

Most artists would probably admit to releasing music before they were truly ready. Do you feel it’s important to be self-aware before making that commitment?

“I’d had offers from other labels, but wanted to do it for the right person and not rush it. There’s a tendency to make music that meets an expectation, but I needed to make a record that had no expectations. That’s quite difficult in itself because expectations give you a guideline and I had no one to feed off.”

The cover art to Bucked Up Space is very abstract. What’s it depicting exactly?

“It’s done by a Brazilian artist called Maria de Lima. I curated a show a few years ago and invited her to exhibit her work but this piece is actually a still from a video. It’s about warped reality and I find that rebounding off visuals helps me to make decisions regarding my sounds. That resonates because you start with an initial idea that begins to turn into something else, especially in a live environment. With all forms of art, the listener brings their own interpretation so it’s interesting that you don’t know what the artwork signifies, but then if you listen to a lot of my tracks you wouldn’t know what the sounds signify either.

The music is fractured but has a propulsive element to it. Is the objective to make people dance or take a more studious approach?

“I’m resigned to the fact that everything I seem to do is a contradiction. When I started making music with KaitO, if the audience responded straight away that would make me happy, but within the experimental world of NPVR and Peter Rehberg, people couldn’t understand what we were doing, which was challenging in itself. This entire journey has shaped who I am.

“I couldn’t make a banging dance album or an experimental album – it had to be between the two, but I’m looking for people to walk away having felt like they’ve heard something different that invokes a conversation. All of these things, whatever they are, are designed to introduce a feeling or a reaction that makes you feel alive, and that goes back to me watching bands like Pan Sonic, who had a massive sound system, and just feeling that sound.”

It must be difficult to describe the music when your creative approach is so multi-layered?

“When you’re in the process of making music, you don’t reflect on it or analyse it in the way that you do when talking about it later. The whole exercise is a process and the idea of putting my work into an album was daunting because I’d got so into improvising music that only exists in the present that committing those ideas to an album that people would listen back to started to make me feel uncomfortable.

I try to keep away from software in general as it tends to add another layer of complexity

“For me, Bucked Up Space doesn’t really have a form – it’s on the edge of everything. I can’t work out whether I’m an artist or a musician because I’ve no idea where my music sits in the genre spectrum, but I guess that’s representative of how everything is becoming nowadays.”

So where did the recording sessions begin in terms of collating various audio for the album sessions?

“I moved to the countryside about six years ago and built a studio with the whole idea of it being set up for me to run a patch and instantaneously record it before using those recordings to prepare for a live show. Obviously, emulating what you’ve done on a modular synth is very difficult live, so I’d take those recordings and re-process them in a live environment, introducing sequenced beats and working various things out as I went along. Then I’d go back to the studio and spend two or three days doing more patch recordings and this went on for a few years.”

How did those sounds evolve into what we hear on Bucked Up Space?

“Over time, I recognised that, due to their tones and textures, the recordings were working together and falling into groups of sounds. I put them into files and, because I’m now able to dial up beats quite quickly, took those ideas to a more professional studio in Margate, which gave me the discipline to create what I wanted the sounds to evolve into. There’s something about walking into a studio and working with an engineer who can instantaneously record ideas and give you an element of feedback.”

You felt it was important to have someone independent to just listen and help you make decisions?

“As I don’t come from a musical background, when you overload yourself with ideas you sometimes ask yourself if it sounds right or is unlistenable. I think there were a couple of sessions where my engineer, James Greenwood, was probably thinking, I can’t do this because it’s too full-on, but he’s got a good recording setup and it was interesting to have him help me introduce triggers and sequences that would create structured tracks out of those experimental recordings.”

In contradiction to the music you make, your home studio is impossibly spotless and well organised…

“I’m so organised that I get excited about the whole regimented process of packing a case and setting up for a show. When I’m using modular synths, making sense of the chaos of using sounds that can escape anywhere means I need to have a blank canvas to walk into. So yes, the studio is white and minimal and all wired up for me to be able to plug in and record as quickly as possible. I’m also aware that when you have too many choices and options you can get to a point where you don’t stick to your initial plan.”

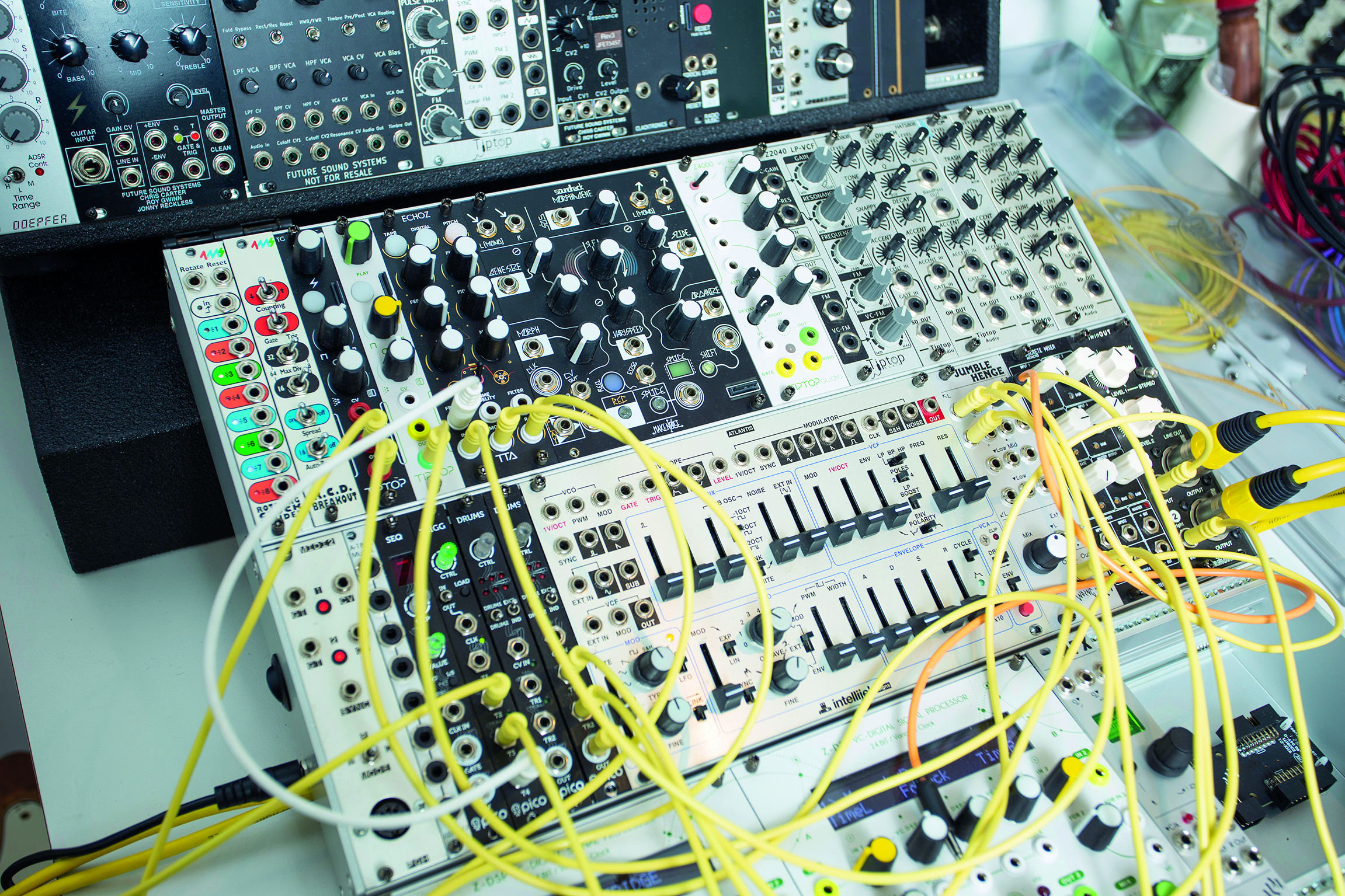

Let’s talk about your modular setup, which is obviously integral to how you get creative…

“I bought an Elite Modular case and started slowly building that up. My first module was the Intellijel Atlantis because it’s a clone of the Roland SH-101 and that felt like an easy place to start. The case has predominantly grown to facilitate using either synth voice or guitar, so there’s a good amount of processing modules like the Tiptop Z-DSP and Make Noise Morphagene, which are an awesome way to mangle the samples that I make. I find it really interesting to have a case full of modular tools that you can get to know your way around, especially in a live environment. It took a while, but now I feel comfortable playing live without having to bring a little patch with me to start things off.”

How much modular gear do you have right now?

“I’ve probably got enough modules to fit into three to six 84HP cases, but I need to start selling some because they’ve become redundant and you have to be really strict with yourself. The great thing is that you can always buy something new to influence your setup. I get really enticed by the ideas behind some of these new modules and their design – or just how they look, which I know is ridiculous, but I’ve recently found that I’m designing my rig to suit how I work on various projects, such as my recent collaborations with Klara Lewis and Alexander Tucker where I sometimes need different points of entry to modular.”

How do you ensure you stay productive with modular?

“I’ll give myself five minutes to work on an idea before moving to the next one, which is kind of harsh because you can get enjoyment from long sessions that go down a particular path, but I was finding myself getting overwhelmed by the amount of material I was creating. What’s so unique and amazing about modular is that while people gravitate towards modular brands like Tiptop, Intellijel or 4MS that probably deliver the same processes, there’s no way you can get the same sound as someone sitting next to you using the same equipment. You have to work and find your own language within the setup that you have.”

Do you have a recording chain set up to get from modular to computer?

“To get different variants of a patch I’ll process it through the Eventide H8000, which is an amazing unit that you could never use live because it pushes sounds as far as they can go. I’ll use the stereo out on the modular but tend not to record a multitude of ideas at once, just one patch giving me one sound and that goes straight into my Mac via a Metric Halo soundcard.

I’ve got an SH-101, the Teenage Engineering OP-1 and the Elektron Digitakt drum sampler and Analog Four synth

“I use GRM and iZotope plugins, but try to keep away from software in general as it tends to add another layer of complexity. The great thing about modular synth sound is that it’s raw and pure and I want to capture as much of that as possible, so I record straight into the Mac and only think about outboard afterwards.”

Are you using any other hardware to source sounds, or for effects processing?

“Not a huge amount. I’ve got an SH-101, the Teenage Engineering OP-1 and the Elektron Digitakt drum sampler and Analog Four synth. They’re just pieces of equipment that I can reintroduce vocals into because recording, manipulating and processing is the biggest part of what I do. I also have an old Fostex reel-to-reel that I use to record on and mess about with the tape.

For vocals, the further away that I can get from my natural voice, the happier I am

“For vocals, the further away that I can get from my natural voice, the happier I am and I’m still trying to understand what I can do on that front. As with the guitar, I’m trying to reinvent the language as far as I can with vocals and it’s fun playing with vocal samples – the delays on the Effectron Deltalab rack have an amazing tonal quality to them that I haven’t found on digital units. It’s the same with the TC Helicon devices, which give you a really clear source. Most of the things I like to work with can be plugged in and give you an instant reaction.”

How did you create the sounds used on some of the more delightfully odd tracks, like Tender Supposition and Absence Pile Island?

“I shifted the titles around at the last minute so it’s hard to remember, but they all derive from the modular. The between section tracks were mainly extracted from samples that were fed into the Morphagene and then manipulated in free form. There are also drones that I pre-recorded using feedback on guitar and triggered used heavy modular processing. With Absence Pile Island I was using the Erica Synths Pico drum programmer to get very tiny sections of sound that could be triggered by sequencers, which I probably put through the Eventide H8000.”

On-stage, where do you draw the line between experimentation and reproducing a track that is vaguely recognisable to the listener?

“That’s something that I’ve been battling with a little because you do have to accept that certain things cannot be reproduced live. I use Ableton Live and do have some pre-recorded synth sequences lined up because dialling in modular sequences is really difficult to do on-stage and would be a massive risk.

You have to accept that certain things cannot be reproduced live

“When I first started playing live, I felt that didn’t matter and for me to feel that the music was real it had to be played in its rawest form, but with a record you do need to compromise and present the work in a way that is relatable for the audience. Having been to a lot of shows myself I know that people usually want to hear the original tracks back.”

You’ve mentioned that you struggle to sleep before a gig, but then you also embrace on-stage accidents. What do you have a fear of exactly?

“The worry is that I might get lost getting to the venue [laughs]. When I’m on stage something takes over and I have a sense that I belong there making these ‘things’. Sometimes your equipment is jumping across the table with vibration, but when you’ve collaborated with so many people at so many live venues, you figure out a way to work with a mistake and bring it into your set. When you reach that point, you can never really make mistakes.”

Nik Colk Void's new album, Bucked Up Space, is out now on Editions Mego.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track