Music theory you can use: pep up your progressions by borrowing chords from parallel keys

Dig yourself out of a diatonic hole

Whether you mean to or not, you’ll almost inevitably work in a particular key when writing a song. You might decide “right, this will be in C minor,” or you might just string together a seemingly random set of chords that, when analysed, happen to conform to a particular key.

Each key has its own set of seven chords that belong to it, from the seven notes of the parent scale of that key.

These are known as the diatonic chords for that key.

Although already a proven recipe for success for many thousands of successful songs, sticking to just seven diatonic chords runs the risk of becoming limiting. What if you wanted to pep up your progression by straying off the beaten track and throwing in some chords from elsewhere?

One way to achieve this is by using what are known as borrowed chords.

Borrowed chords are usually taken - or, yes, ‘borrowed’ - from the key parallel to the one you’re working in. Parallel keys simply have the same root note, or tonic, as each other - for instance, C major and C minor are parallel scales, as they both start from the note C.

However, when harmonised, the notes in the C minor scale produce a different set of chords to the notes in the C major scale. It’s these chords that you can borrow to embellish your major progressions, like so...

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

12 steps

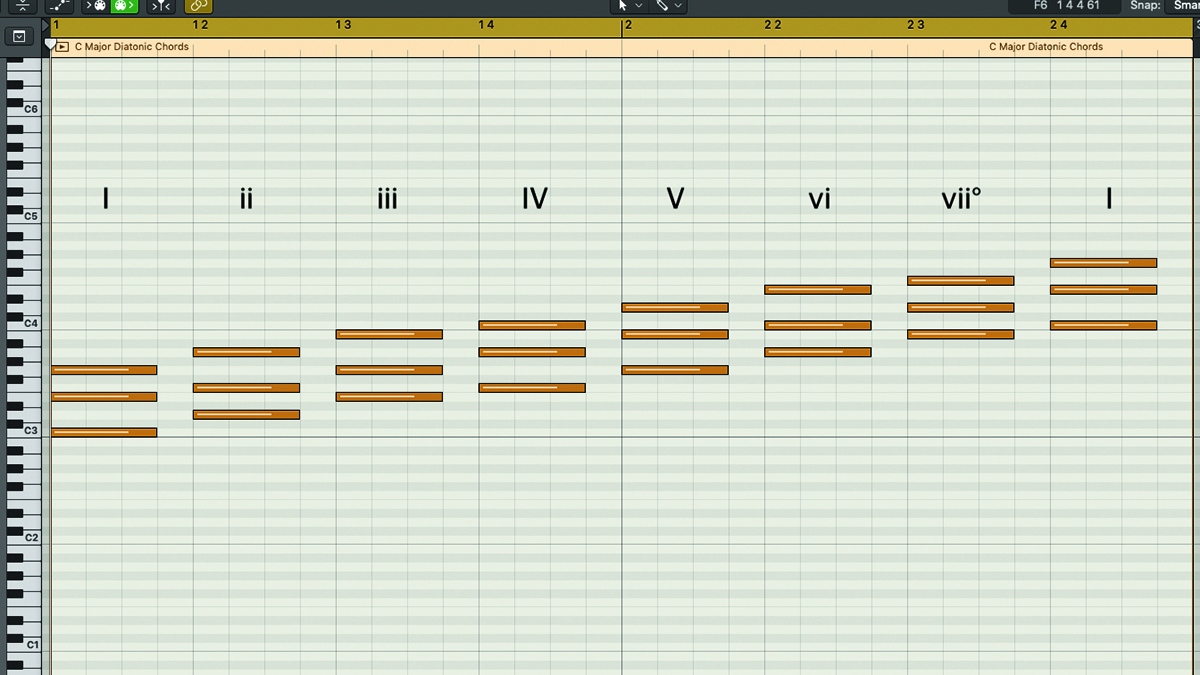

Step 1: A diatonic chord means a chord that only uses notes from the parent scale of the key, so the diatonic chords for C major, for example, will be built off the notes of the C major scale. Diatonic chords in any major key can be labelled as I – ii – iii – IV – V – vi – viiº, where upper case Roman numerals denote major chords and lower-case numerals denote minor chords.

Step 2: So in the case of the key of C major, the diatonic chords will be C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am and Bdim. While this is certainly a good selection of chords to get us off the ground, with thousands of possible progression permutations, having only seven basic chords at your disposal does tend to limit your horizons somewhat.

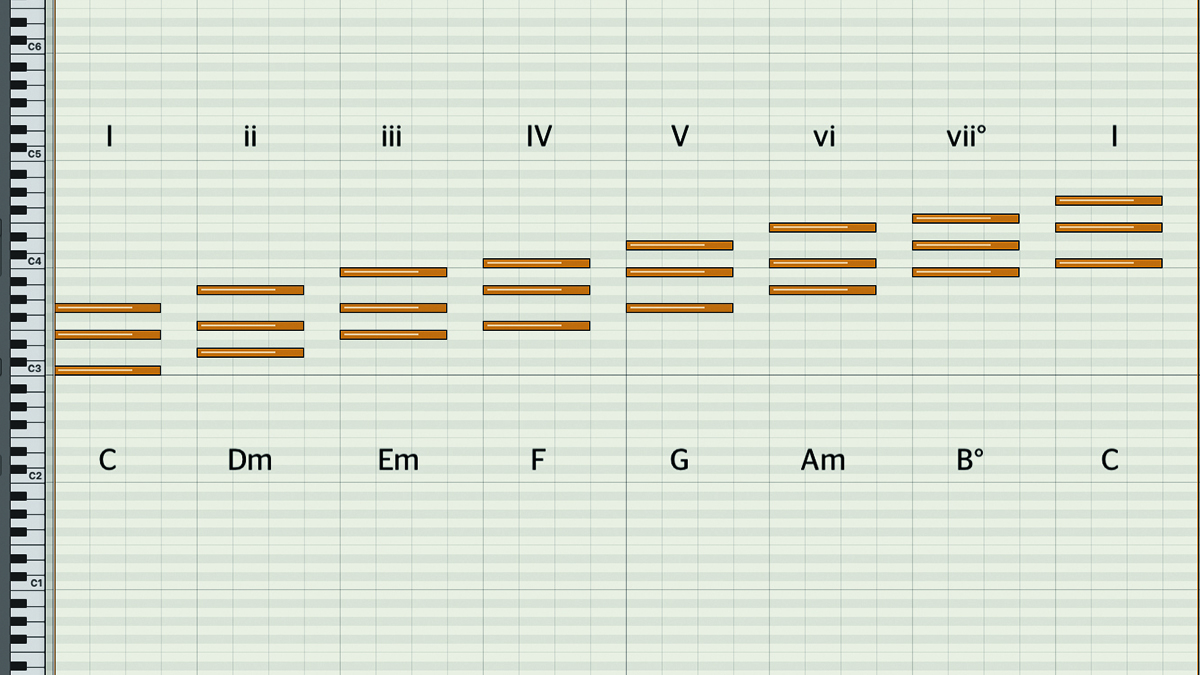

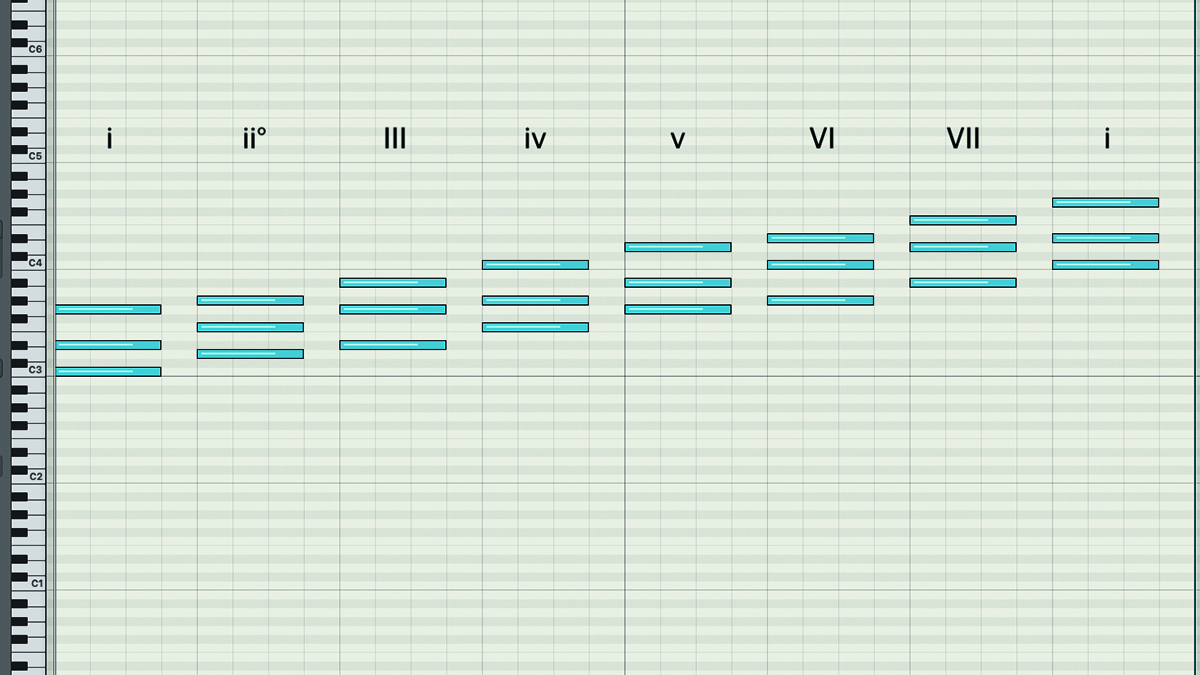

Step 3: So let’s explore some other chord options we could ‘borrow’ to add to a C major progression. In contrast to the diatonic chords for a major key, those for a natural minor key follow a different pattern: i – iiº – III – iv – v – VI – VII. These are the triads you get when you stack thirds onto each note (or ‘degree’) of a natural minor scale.

Step 4: Borrowed chords are most often taken from a parallel minor key, and the parallel minor key to C major is C minor. This is because it starts on the same tonic note of C, but is based on a minor scale rather than a major one. So following this pattern, the chords that are diatonic to the key of C minor are Cm, Ddim, Eb, Fm, Gm, Ab and Bb.

Step 5: When you use borrowed chords, all you’re doing is taking chords from the parallel minor key and using them alongside chords from your major key. So if you were writing in C major, you could pinch any of the chords from C minor and use them. Or, if the song was in C minor, take chords from C major and use those with the diatonic C minor chords.

Step 6: To illustrate, let’s take a standard I – vi – IV – V progression in C major, using the palette of chords listed above. This gives us C – Am – F – G. A pretty standard progression, but we could make it more interesting by swapping one of these chords for one that’s borrowed from the key of C minor. We can take our pick from Cm, Ddim, Eb, Fm, Gm, Ab and Bb.

Step 7: Looking at the substitute chords available in the key of C minor, we pick and choose one to swap. When working in major, the typical chords borrowed from the natural minor key are iv, VI, VII, and, if you’re feeling a bit jazz, the iiº. So, how about switching the F chord (IV) for an Fm (iv), giving us C – Am – Fm – G? This lends the progression a different feel altogether.

Step 8: Here’s another example, based this time on a I – iii – ii – V progression, which in the key of C major would give us C – Em – Dm – G, as shown here. We can use a borrowed chord as a passing chord to smooth out the transition between the iii chord (Em) and the ii chord (Dm).

Step 9: The logical choice would be an Eb chord, which is the III chord of the harmonised natural C minor scale. It makes sense as its root note of Eb provides a chromatic step down, or single-semitone descent between the Em and Dm chords, so it works great as a passing chord. Since it’s an inversion of Eb major, the root note appears in the centre of the chord.

Step 10: Here’s a version that uses seventh chords and different inversions. Once you start to use borrowed chords with more complex voicings, it can really ramp things up a notch. There’s also a sneaky G7 > Db7 tritone substitution on the V chord here, where we substitute one chord for another whose root note is a tritone (six semitones) away from the original.

Step 11: Our final example this month features a completely diatonic progression in C major: C – G – Em – Am – F – G – C. (I – V – iii – vi – IV – V – I). We’re going to borrow a bunch of chords from the key of C minor, once again, to make things a little more interesting. Let’s take Eb, Fm and Ab – the III, iv and VI chords.

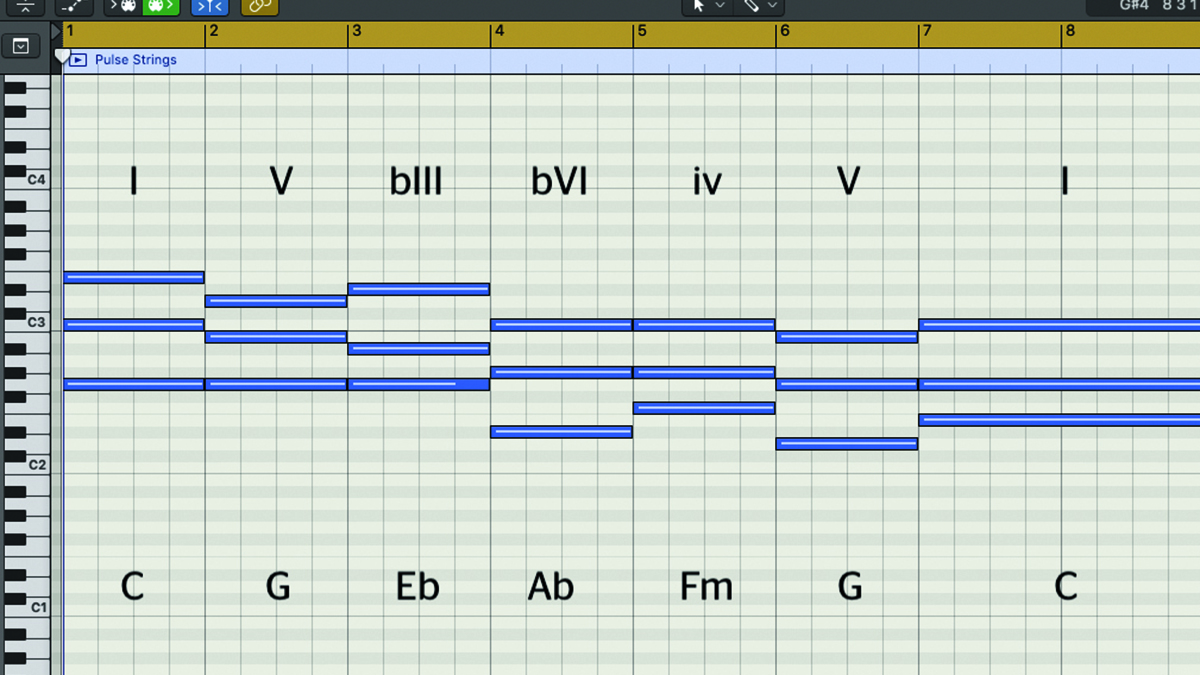

Step 12: So now we switch the Em in our original progression for an Eb, the Am for an Ab and the F for an Fm. This results in a new progression of C – G – Eb – Ab – Fm – G – C. (I – V – bIII – bVI – iv – V – I). This now becomes almost a minor progression in its own right, except for the fact that it resolves back from G major to the C major chord at the end.

Parallel vs relative keys

The terms ‘parallel key’ and ‘relative key’ are often mistaken for each other, when in fact they mean two different things. Whereas parallel keys share the same root note, relative keys share all the same notes, but just start the scale from different root notes. Using C major as an example, its parallel key is C minor, as they share the same root note, or tonic – C. The relative minor of C major, however, is A minor, because the A minor scale uses all the same notes as the C major scale, just starting from A instead of C.

Minor differences

As well as using the natural minor scale as a source of borrowed chords, you could find yourself borrowing diatonic triads from the harmonised melodic and harmonic minor scales too, which would add even more variety of choice by throwing some augmented and diminished chords into the mix.

The harmonised C minor harmonic scale gives you the diatonic chords Cm, Ddim, Ebaug, Fm, G, Ab, and Bdim, while the C minor melodic diatonic triads are Cm, Dm, Ebaug, F, G, Adim, and Bdim.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.