Explained: The music theory behind songs from Deadmau5, Floating Points and Frankie Knuckles

Let’s find out how progressions, melodies and compositional techniques have been deployed in electronic music from successful artists

Over the past week, we've been covering how to use music theory to help you make better electronic music. However, discussions of theory can sometimes – to state the obvious – all come across as a bit theoretical. It’s easy to discuss concepts such as scales, modes, chord voicings and the like in isolation, but that doesn’t always make it easy to put these ideas into practice.

You may, for example, grasp the concepts behind turning a simple progression or melody into something more elaborate, but how much complexity is really necessary? Does the two-note bass riff you like so much have enough to sustain a listener over several minutes? Is your lead line too obvious? Or too noodly?

5 music theory tools to help you make better electronic music

The obvious answer to all of these questions is that you should trust your ears. If your track sounds good to you, then that’s what matters, no matter how right, wrong, complex or simple the theory behind it happens to be. The problem behind this, however, is that sometimes trusting your own musical instincts is easier said than done; particularly if you’ve been listening to the same chords, riff or bassline on repeat during a long studio session.

Sometimes, the best way to evaluate and inspire your own songwriting is to compare it to the work of an artist your admire. To tackle this head on, this issue we’re exploring the theory and musical concepts behind a trio of lauded dance music tracks.

With decades of amazing electronic music to pick from, settling on three tracks to explore wasn’t an easy task. We’ve opted for three from different eras, each by a lauded producer, and each presenting a unique and melodically interesting approach to making electronic music.

First up is a laid-back Chicago house classic from Frankie Knuckles, which pairs wistful synth flute with a funky club beat. The second, from Deadmau5, is electronic music rooted in baroque composition and channelled via the influence of synth icon Wendy Carlos. Finally, our most contemporary track comes from one of the most inventive musicians in the game right now, Floating Points, known for his ability to channel jazz influences through loose electronic structures.

This trio is hardly a fully representative cross-section of the history of dance music. For obvious reasons, we’re leaning towards the melodic side of things, ignoring the swathes of great dance tunes that have been made out of just two or three chords, if that. But we hope they’ll inspire some ideas of how chord progressions, rhythmic ideas and varied influences can be deployed in your own music.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

1. Frankie Knuckles - The Whistle Song

A seminal early Chicago house classic track, the original version of The Whistle Song is a track found on Frankie Knuckles’ 1991 album Beyond the Mix. For clarity, we’re examining the EK 12” mix of this tune, which has different instrumentation to the album version, swapping out the original’s real flute for a synthetic version.

In the key of C major, this iconic floor-filler takes the form of a simple, alternating two-chord pattern, switching between two bars each of CMaj7 and FMaj7. The CMaj7 is played in the 2nd inversion (G, B, C, E), while the FMaj7 is voiced in root position (F, A, C, E). Interestingly, when swapped around and played with the FMaj7 first, followed by the CMaj7, this alternating progression forms the basis of Gymnopedie No.1, a very famous, wistful piece of classical piano music composed by Erik Satie in the early 1900s.

The chords are then backed up by a round, analogue synth bass part that highlights root notes and fifths, which are playing a skippy, offbeat pattern in classic Chicago house style, locking in the swung feel of the 909-sourced drums.

Arrangement-wise, things are very basic, the main drum, bass and chord parts never letting up for a moment. Meanwhile, over the top, the track’s topline consists of two main parts. The first is a kind of freeform synth flute noodling, largely improvised over the top of the chords. But what’s really going on in the piece?

Music theory basics: how to understand musical modes and use them in your songwriting

When you look at what this synth is playing, it never strays from the white keys, regardless of whether it’s played over the CMaj7 or FMaj7. This is no real surprise, as the notes of the C major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A and B) can be found in both chord shapes. However, when the chord changes to FMaj7, with an F in the bass now dictating the tonal centre, playing the notes from the C major scale over this chord results in a subtle change of mode from Ionian (the major scale) to Lydian.

The Lydian mode is what you get when you play the notes of the scale from the fourth degree of the scale rather than the root note, resulting in a different pattern of intervals between the notes. The fourth degree of the C major scale is F, so if we play all the white notes from F to F, with an F in the bass to give it its tonal centre, we get F Lydian; an F major scale with a sharpened fourth degree. The Lydian mode has a whimsical, lighthearted quality about it, which is why the synth riffing sounds so uplifting.

The second topline part is the famous whistle hook itself, which follows a similar example to the synth flute, avoiding any black notes. This is played by a synth sound made up of what appears to be two square waves tuned a few cents apart, giving it a kind of human, slightly out-of-tune aspect, which is then enhanced by some sort of pitch envelope modulation that seems to make the tails of the notes fall away in pitch slightly.

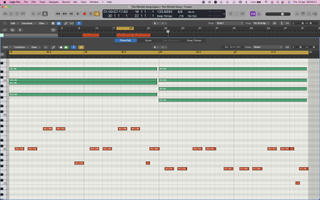

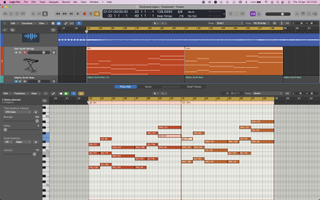

The track only contains two alternating chords – CMaj7 (G, B, C, E) and FMaj7 (F, A, C, E) – played in 2nd inversion and root position respectively. Here’s how they look in the piano roll editor, together with the synth bass part. Each chord lasts for two bars, an arrangement that persists for the duration of the song.

The whistle hook plays a repeating figure over both chords. Starting on G, the fifth of the C chord, it leaps to a D note, which when played over the CMaj7 chord gives it the feel of a CMaj9 by adding a high D to the original chord: C, E, G, B, D. It then repeats over the FMaj7 chord, almost like an echo, emphasising the track’s ‘call and response’ feel.

The synth flute noodling also only plays the white notes. Over the Cmaj7 chord, this translates to Ionian mode, but over the FMaj7 things take on a Lydian feel. This is explained by playing the notes from the C major scale from F to F instead of C to C. Here’s an example of a short, one-bar section taken from around the 40-second mark.

2. Deadmau5 - Clockwork

The root of this song, believe it or not, goes back over 300 years in the form of a 1695 composition by the English baroque music composer Henry Purcell named Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary.

In 1971, composer and Moog aficionado Wendy Carlos famously based her theme music for the notorious Stanley Kubrick movie A Clockwork Orange on this Purcell piece. This soundtrack then later provided the inspiration for Cygnus X’s The Orange Theme, which then itself became the inspiration for Clockwork. Quite a journey!

It’s the mechanical, cyclic nature of the chord progression here that fascinates and delights, continually modulating (changing key) with the mathematical precision of a clockwork device. At the same time, the continuous shifting from minor to major tonality and back again brings us constant dramatic tension.

The track begins with an extended drum intro accompanied by a sustained Bm chord, and it’s from this that our cycle begins. The progression is based on a series of six-chord mini-progressions, building blocks that Purcell uses to create an ever-ascending cycle that see-saws between heartache and majesty. Our first set of six chords takes this form:

Bm > Em > F#

F#m > D > C#

aka

i > iv > V

v > III > II

deadmau5: “The Moog Voyager - I can't seem to escape that synth. It’s the last good Moog”

Normally in a natural minor diatonic set, the ii chord should be a diminished chord, but the sixth and final chord in each set here is always a major II chord, which isn’t diatonic to the key. Likewise, the third chord in the set is a non-diatonic major V chord, but this always resolves to a diatonic minor v chord for the fourth chord. When a progression uses chords that aren’t part of the diatonic set like this, they’re known as borrowed chords, as they’ve been borrowed from another key.

Once we’ve played through our six-chord set, we simply turn the final chord in the first set from major to minor, by flattening the third by one semitone, and begin the cycle again. That major II chord from the end of the previous set becomes the minor i chord that begins the next set in the new key. The result is that each subsequent set begins a whole tone higher, so the piece builds in a seemingly never-ending spiral.

This is a tactic that Deadmau5 uses to great effect in the mid section, opening the filter envelope on the chords brighter and longer as we move up the progression, reaching onward and upward toward a release that seems constantly out of our reach.

Every time that last major chord in each set hits, it’s like the sun breaking through the clouds. Rather satisfyingly, because there are 12 notes in an octave, after six sets that each move up a whole tone (two semitones) apiece, we end up back at our original Bm starting point. Played in all six keys, it’s actually a really good practice exercise!

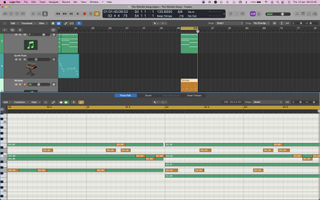

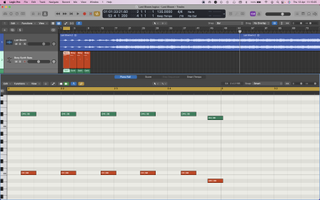

The chords for each six-chord set can be represented by the Roman numerals i > iv > V > v > III > II, with lowercase numerals representing minor chords and uppercase numerals representing major chords. In this illustration, we’ve pictured our first progression in Bm, resulting in the chords Bm > Em > F# > F#m > D > C#.

Each set transitions by shifting the last chord of the first set from major to minor, which effectively starts the six-chord cycle from scratch, but in a new minor key rooted two semitones from the last. So here, the borrowed major II chord of the old Bm set (C#) flattens its third (F>E) to become the minor i chord (C#m) of the new C# minor set.

The root chords that begin each set then, are: Bm, C#m , Ebm, Fm, Gm, Am. After six sets, we end up back at our original Bm startpoint. Over the 11-minute track, we go round the sequence six times, with different instrumentation, builds and drops each time, before we hit the 10 minute mark and pedal on a Bm chord for a 1-minute runout.

3. Floating Points - Last Bloom

A delicately beautiful amalgam of skittery modular beats and runaway synth arpeggios, at first listen Floating Points’ Last Bloom seems like a relatively structureless wander through an experimental soundscape without much actual theory involved. But if you know anything about Sam Shepherd (the man behind Floating Points) you’ll realise that a lack of theory knowledge is anything but the case.

If you know anything about Sam Shepherd, you’ll realise that a lack of theory knowledge is anything but the case

What we have here, then, is one of those occasions where a lot of effort has been put into making a minimalist end product that on the surface appears abstract in nature, but when you dive deep, a very well-thought out structure does become apparent. Shepherd’s random tweaking of the envelopes and pattern programming of the modular synth providing the drum track only serves to reinforce the resulting feeling of randomness as the track progresses.

Key-wise, the music doesn’t appear to be completely in concert, which made it entertaining for us to work out the key that it’s in. After playing around with the tuning a little, we settled on a base key of C minor, although the recorded version presented around 35 cents sharper than that overall.

We start with an intro part played by two separate synth lines in harmony, namely a bass part and a top line, woody-sounding pluck synth that’s a little out of tune. It’s only when the ragged analogue drum beat kicks in at around 30 seconds that we realise this is actually an anacrusis – a phrase that’s played across the beat, on the off beats.

Until the drums start, we’re led to believe that the first note of the repeated phrase falls either on the downbeat, or on the second eighth note of the bar, depending on how you first hear it, when in fact it falls one sixteenth-note between the two.

Floating Points: “Recording at 96kHz is definitely not cool… it’s completely pointless!”

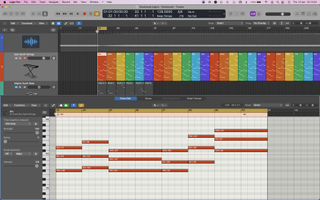

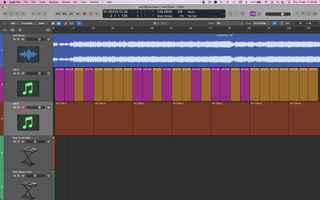

The main body of Last Bloom is a captivating sonic journey that appears largely formless at first glance, with no real discernible chord progression in the normal regard, but somewhere in the mid-range we detected a constantly repeating pattern of tones that form something akin to a bassline around which we could start to hang a structure of sorts. This takes the form of two alternating four-bar patterns, each containing four ‘bass’ notes – we’ll call them A and B – which we then discovered had been grouped together in larger pattern combinations, as illustrated in pic 3 below.

Beautiful bleeps and bloops abound throughout, with arpeggiated flourishes punctuating things regularly. Everything is based around the notes of the C natural minor scale, and we never really get to hear the same riff twice at any point. Then suddenly, at the 3.30 mark, the track as we’ve known it up until this point in time devolves into a shuddering, sustained gated, swirling Cm9 chord (C, Eb, G, Bb, D). This takes on a choral vocal quality, after 30 seconds or so, after which point the track abruptly ends.

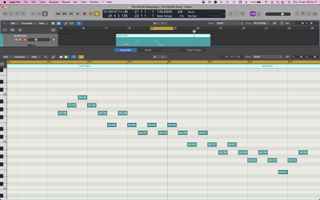

The first thing we hear in the track is this syncopated phrase played by a bass tone and woody synth playing in harmony. Taking into account that we’re in the key of C minor here, we’ve got the bass tone playing the notes C and Bb and the woody synth complementing it with Eb and D.

The track’s main melodic centrepiece consists of largely improvised synthwork of very high complexity and quality, based around the C natural minor scale. As an example, we’ve singled out this little rhythmic pattern that floats into the track at around 1:30.

Section A contains the core notes Ab, G, Bb and Eb, while section B contains the same notes in a slightly different order: Ab, G, Bb and Eb. When you see how the track is made up using these sections, a pattern emerges where the four-bar A and B sections can be grouped in sets of four, totalling three 16-bar combos to construct the track’s body.

Dave has been making music with computers since 1988 and his engineering, programming and keyboard-playing has featured on recordings by artists including George Michael, Kylie and Gary Barlow. A music technology writer since 2007, he’s Computer Music’s long-serving songwriting and music theory columnist, iCreate magazine’s resident Logic Pro expert and a regular contributor to MusicRadar and Attack Magazine. He also lectures on synthesis at Leeds Conservatoire of Music and is the author of Avid Pro Tools Basics.

“A musical style, defined by plaintiffs as ‘pop with a disco feel’, cannot possibly be protectable”: Dua Lipa wins victory in Levitating court case as judge rules that there is no copyright infringement

“At the time, I wasn't, like, the coolest kid, and people didn't want to be in a band with me”: Ed Sheeran explains why he started using looper pedals, then demonstrates one by performing a number one hit that he wanted to give to Rihanna