How misusing vintage outboard gear changed the world of recorded music - and how software effects will do the same for its future

We survey some of the best examples of when vintage studio outboard gear was pushed beyond its intended use, with the resulting recordings going on to make a huge impact

It might be that we *whisper* sometimes give too much credit to music gear here at MusicRadar, and put it on pedestals reserved for human genre creators and influencers. However, there are many examples of studio gear that were released, and then used and abused to major effect, and it’s these that deserve more respect.

But we’re not talking about instruments, like when Chuck Berry (arguably) played the first rock riff on an electric guitar, or when Phuture invested not a lot of money in a TB-303, and pushed it to extremes to help invent dance music. No, those are way too famous and, frankly, sexy.

Instead we’re going more geeky and looking at some of the best examples of when vintage studio outboard gear was pushed beyond its intended use, with the resulting recordings going on to make a huge impact. A time when producers who, perhaps more than by accident than intention, misused their gear and the mistakes made history.

Start off gentle

One of the earliest examples of a studio tool being misused was the Pultec EQP-1, which began life as a passive EQ in the 1950s, but after a gain stage was added in 1961, became the more famous and beloved by studios, Pultec EQP-1A. This gave the gentle EQ a character that would add tube presence to anything, but it was the instruction manual’s advice never to boost and cut frequencies at the same time that gave rise to the infamous Pultec low end trick.

Put simply, producers found that selecting its 60Hz setting, and then simultaneously boosting and attenuating gave low end sounds a more rounded character. OK, this wasn’t exactly radical abuse but it was a start and producers found that the unpredictable analogue design of a lot of audio gear used in recording could be exploited.

Another classic piece of gear was the UREI 1176, and it was largely a classic because of an accidental feature, this time giving rock mixes some clout. It has four set ratios at 4:1, 8:1, 12:1 and 20:1, and one clever wag of a studio engineer decided to see what would happen if all four were used simultaneously. Thus the ‘British Mode’ was born because of the edgy rock sound that it imparted on mixes.

Even more radical was the Roland Space Echo, which when pushed to its limits helped take dub to some incredible sonic heights (and arguably dubstep too). This tape-based delay and spring reverb has 12 settings to switch between various tape head and spring combos.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The dub genre came out of reggae in the ‘60s, but in the ‘70s producers like Lee “Scratch” Perry and Errol Thompson used the Space Echo for the now instantly recognisable repeated echoes and twisted sound effects. These could be used on any instrument or voice to create the ultimate music scene, and all helped along by a somewhat odd Roland unit pushed to its edges (well Roland would have more form with that later, of course).

Present day effects

After those early ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s studio misuses and abuses, the ‘80s became all about ironing out the mistakes. And after one or two false starts with digital technology, the goals were high kHz and MHz, low noise and mass use of Pro Tools.

But that wasn’t quite the end of the story. Perfection is not what it seems. After years of being ignored, analogue studio gear – like synths – swept back into fashion, or, more likely for those of us who couldn’t afford the hardware, swept into plugin form.

Now there are emulations of all sorts of analogue gear to bring back those sonic imperfections – tape delays and saturators, vintage compressor emulators, and so much more. But what of the new breed of effects? What can they bring to the eccentric studio party? Can software be as idiosyncratic as that 70-year-old compressor? It turns out it can.

A new dawn of disuse

We are enjoying a truly incredible time in the world of software effects, with more and more developers making the most of more and more processing power to challenge the old guard and old ways of thinking with their wares. Baby Audio’s recent Humanoid, for example, could be used and abused to create a new style of vocal effect that might even become as important (but maybe not as irritating) as AutoTune.

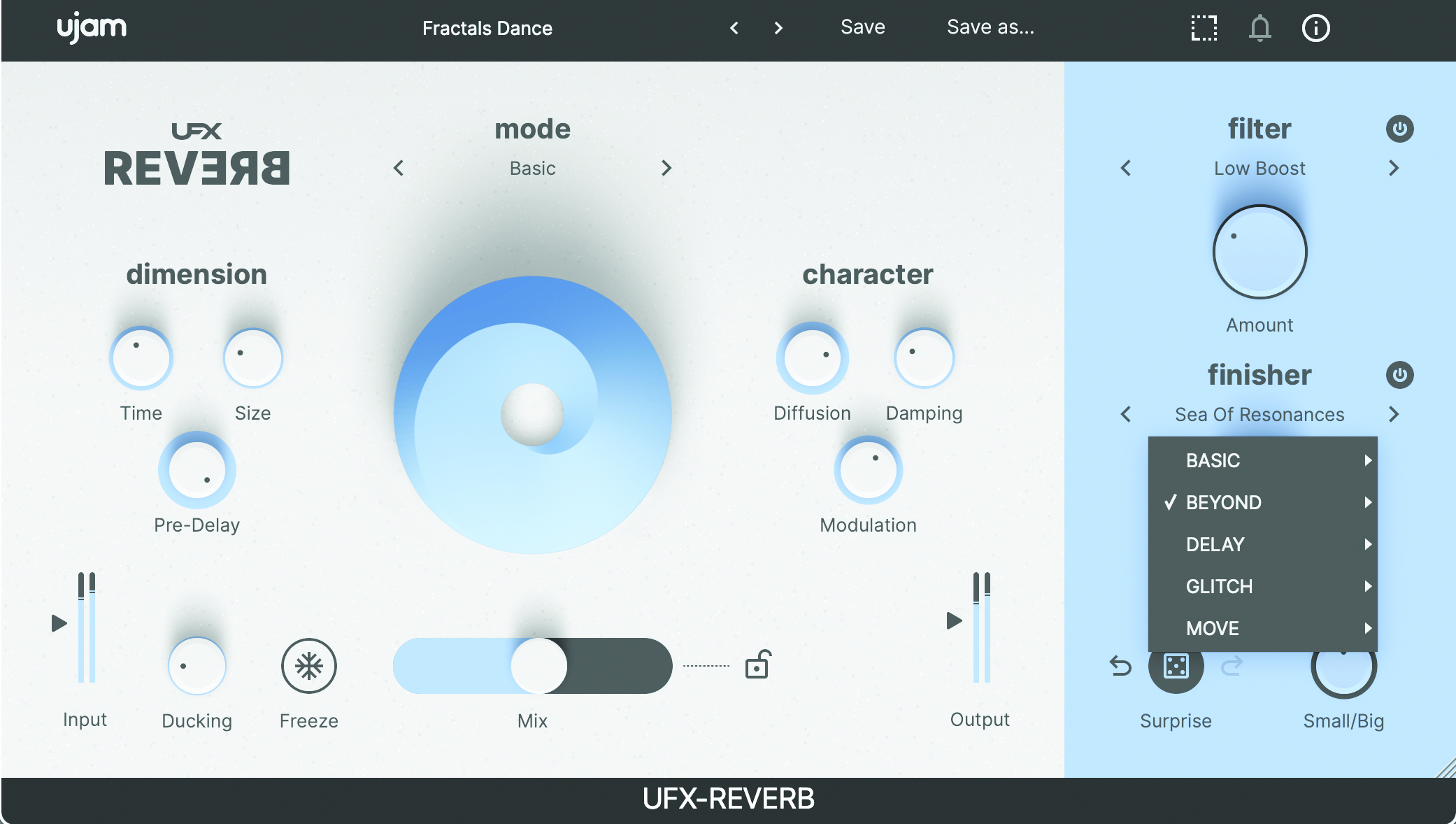

Elsewhere UJAM, with its UFX reverb, isn’t even saying what AI is behind the title, but the assumption is that there is some involved, because this software’s algorithms are so mighty at blending different styles, that every time you hit UFX’s random dice button to create a new effect, it’s brilliant! So if you don’t create a music revolution with that accidental effect, someone will. (Or, more likely, AI will.)

And talking of AI, we’ve got plugins that can quite easily make your entire album ‘just sound better’ in an instant. What does all this great-sounding music mean? That we’re back to ‘80s perfection, or that, more likely, someone will take the concept and throw it on its head.

In many ways we’re at a cusp of something quite incredible with software effects. The above and more – Pluralis, Ripple Phaser, Bloom, even good old Guitar Rig – can all be made to make mistakes. Sure AI will probably and invisibly make our music sound perfect, or perfectly noisy, but it’s going to be a human that twists the algorithm into some new sounding, twisting the perfection into non perfection. We’re humans. We’ve always been good at that.

Creating a new genre with Baby Audio’s Humanoid

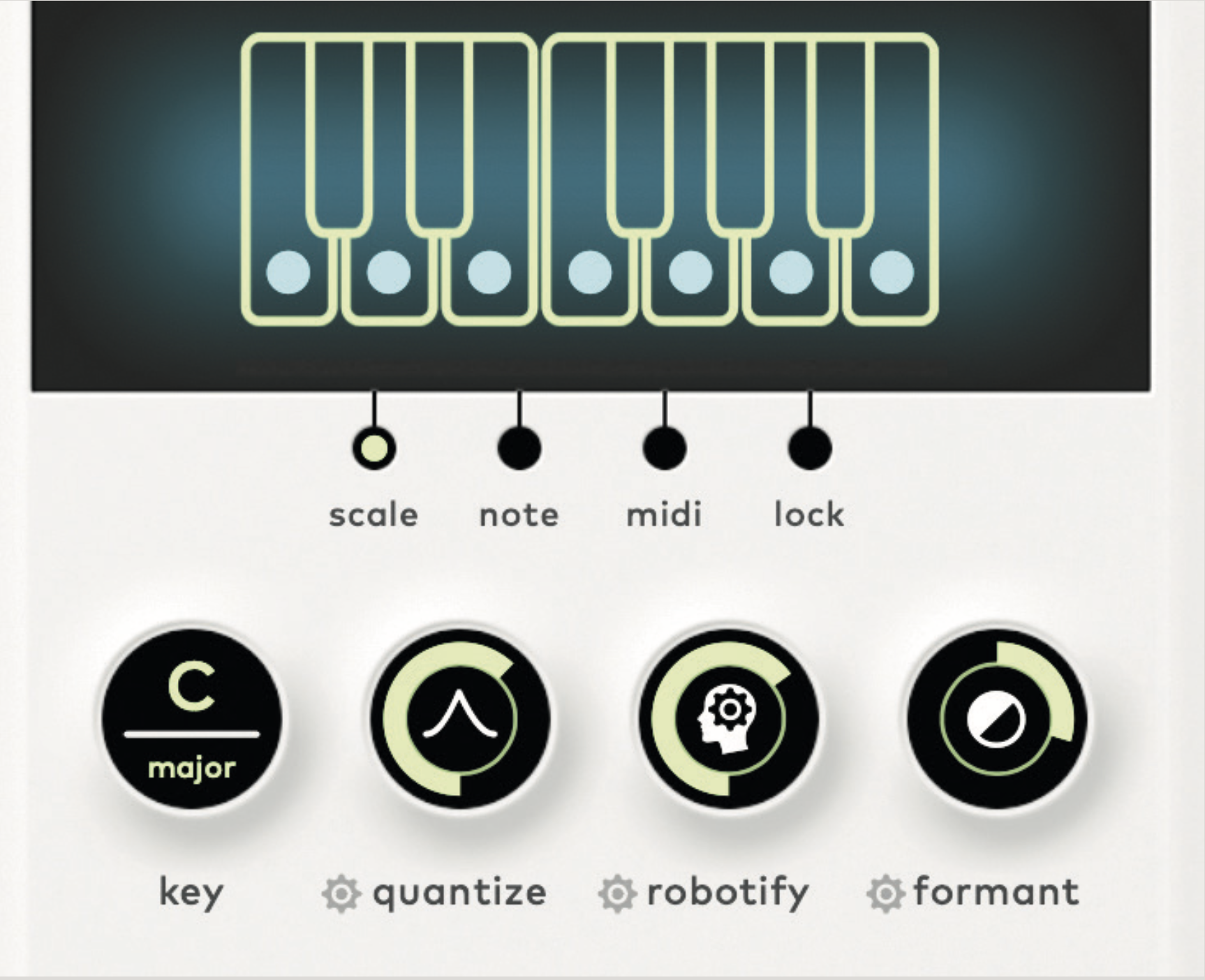

Baby Audio’s new Humanoid is a vocal processor with a difference. It has a Synthesize feature that transforms vocals into any waveform you like, so effectively creates a synth sound out of them.

But what if we go off road, put a guitar through it, and turn it into a robot vocal and then a synth sound?! The first part is easy, just up the Quantize and Robotify levels for more robot style voweling, and use the Formant to go male or female.

Then we use the central area to up the Transformation of our guitar vocal into a synth. The result is… alien. But we think we’ve just invented a new genre.

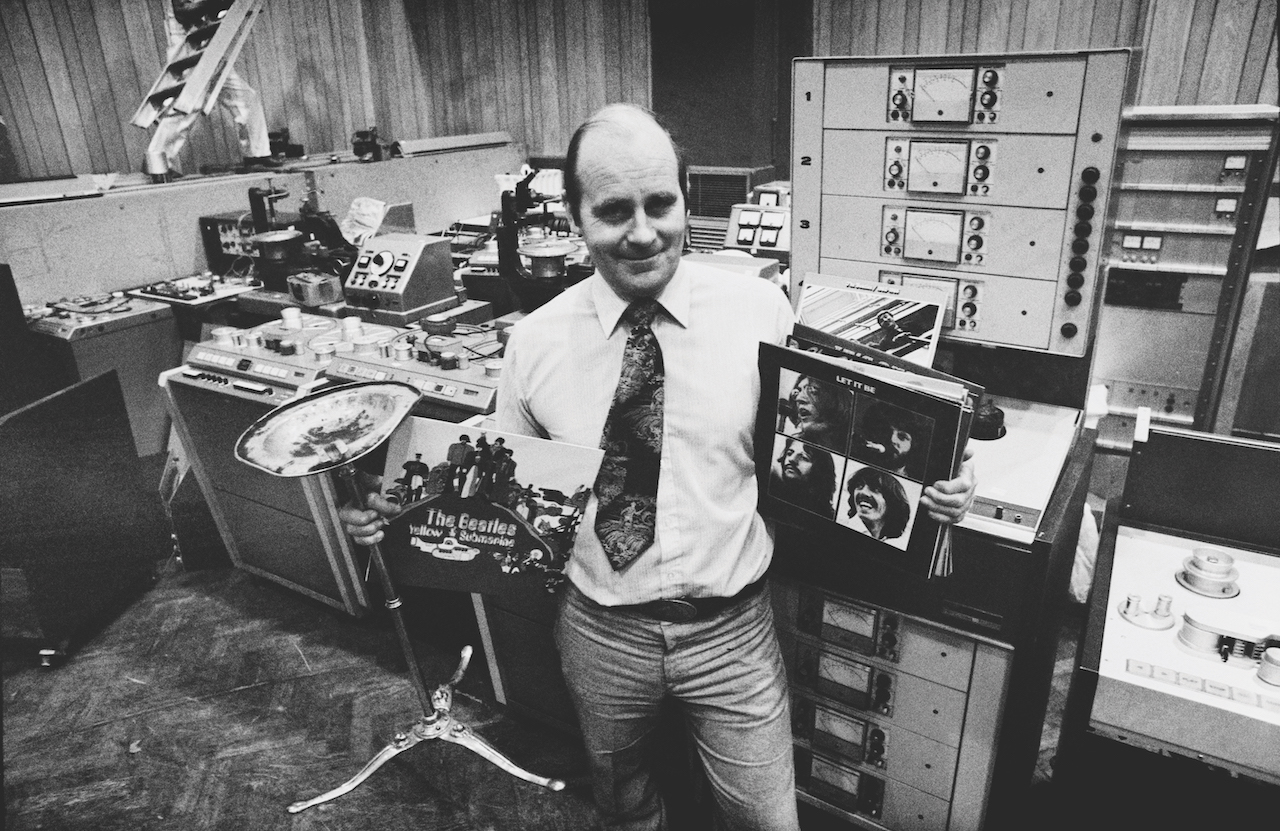

The Joe Meek effect

Joe Meek was one of the first producers to really exploit pushing audio gear to its limits, cutting his teeth as a studio engineer in the late 1950s. On a very simple level, but radical at the time, he would send everything to the max, getting compressors to pump and limiters to deliver such hot signal levels that everything was at a maximum, at the same level on tape, so mixing requirements were at a minimum (as mixing gear was also at a minimum).

Meek was such a studio geek – some say the first studio geek – that he ended up building a lot of his own gear

But it was his radical studio practices that really sealed the studio deal, and according to who you believe, he invented close miking (to focus on the target and reduce room noise), artificial reverb to lessen the need for said room sound; he created synced delays, was one of the early pioneers of multi-track recording, and pushed the width of stereo. Wow, that’s quite a CV, even if some of it is in doubt.

Meek was such a studio geek – some say the first studio geek – that he ended up building a lot of his own gear. But it was known that he owned Fairchild and Altec compressors, so if you own either, you too can go Meek. For anyone else, check out our compressor and EQ tutorial.

Joe Meek’s hard compression (and his EQ settings!)

Meek would go all out with his compression and while we don’t have either his Fairchild or Altec to hand, we can get hard compression fairly easily in plugin form. We’ll start with fast attack and release times, so set these to around 10-20ms and 100ms respectively.

Now we set the Knee dial to a maximum and dial the Threshold to 10. You should start hearing an increase in punch. We’ve now pushed the Ratio and Makeup dials up. Experiment with these until you get as much pump as you wish.

Finally, according to an online fan page, the frequency spectrums of Meek’s Tornados and Heinz recordings were as follows: “the bass is particularly present at 125Hz, the mids at 2.5 and 6.3kHz, the highs at 8kHz”, all of which Meek tweaked with an early filter.

The ultimate gear misusers

As more ways were discovered to use recording gear in more colourful ways, artists and producers were asking what that meant for their music, none more so than The Beatles. Alongside Joe Meek, producers like George Martin pieced all the gear together to see the studio itself more as a creative tool or instrument. The Beatles, Martin, and studio boffins like Geoff Emerick and Ken Townsend became the ultimate gear misusers – or as they might prefer, experimenters.

Yes it might have been because Martin and team had access to the best equipment, but when they got it, they weren’t afraid to take it away from its chosen path. Record John Lennon through a Hammond Leslie speaker, you say? Why not? Play a bunch of tapes backwards and see what they sound like? Hell yes. Splice together two completely different takes of the same track and shove it in the song? Give it a go!

By the time they were done, Martin et al had solidified multitracking as an art form, had a good shout as the first band to sample, made the Minimoog ‘a thing’ that could be used in the recording studio by a guitar band, turned guitar feedback into an instrument, and invented flanging (almost).

Most of these ideas came from the band’s devil may care attitude, but Martin, Emerick, Townsend and more were the bridge between the ideas and analogue. It’s unlikely that we’ll ever see this kind of creativity in a studio again (nor so much gear getting a kicking).

Experiment with Minimal Audio’s Ripple Phaser

Minimal Audio’s new Ripple Phaser takes phasing to new heights, widths and depths. It can sound like a 24 peak phaser – already quite cool – or a lot more.

This preset, for example, turns a plucked guitar into a swirling, peaky pad that moves around the spectrum like a ghost in a far off cave. For the first time, presets are worth fully exploring.

With this one, our guitar now sounds like it has a ticking clock under it – pan right and it’s a kick drum under Captain Kirk shooting someone. Make mistakes with this one and it doesn’t matter – you just may be the future of music.

Dub effects in the Roland Space Echo: putting our theory of contrary gear use to the test

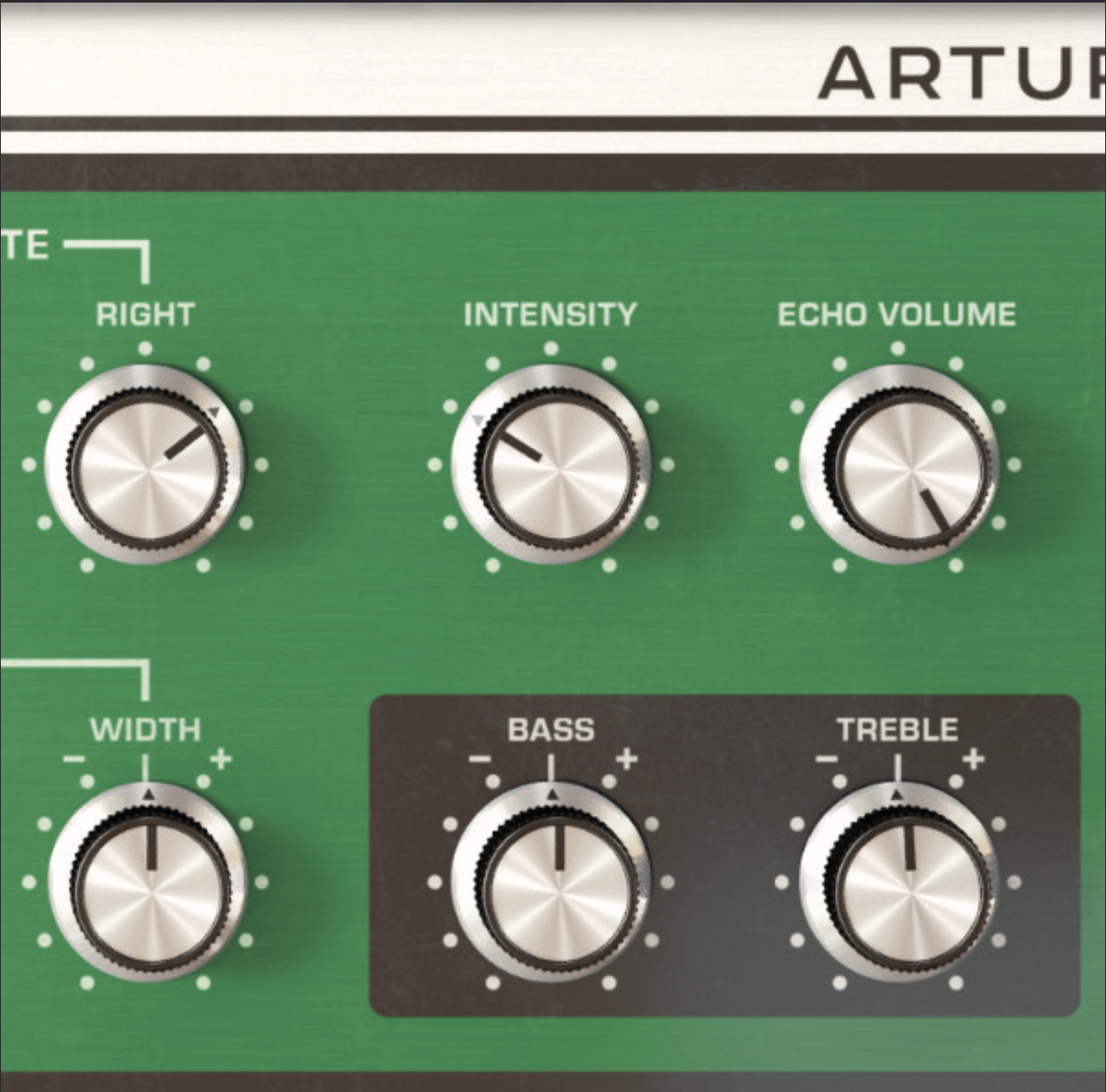

All sorts of creative effects can be squeezed out of a Roland Space Echo, so here’s a rundown of this curious device and how to create some classic dub effects. From left to right, you start with 12 main modes based on how the echos are combined with the delay, and which delay heads they use. We’ve set it up with some drums going through it.

Set it to mode 1 and you already have a fairly dubby laidback sound. Now adjust the two (linked) Repeat Rate dials and you’ll hear some amazing pitch effects as the virtual tape is sped up or slowed down which alters the time between the initial sound and its repeat.

Now try the Intensity dial – and you’ll need a delay for this to do its thing as it controls the number of echos, and may not do anything until it gets a repeat. Push it up and the Space Echo will eventually reach self-oscillation. Here we’ve set it up with our beats for the perfect dub break, with a touch of that lovely reverb.

Now we’re going proper dub delay with a bass sound, using one of the Arturia plugin version’s presets as a starter. Here we’d say take the Stereo Rate Offset and Width controls back to a centre point as these control how the bass works in stereo (which you might not want!).

Now we’re back on the Default settings but with a vocal. The Space Echo is amazing with vocals as you can get some weird and whacky effects. Try these settings and move the Repeat Rate dials in real time for some dubbed up vox.

Finally we’ve upped the stereo spread of our repeated vocals and increased the dub with the Intensity dial and it’s truly mesmerising; the unit that launched a genre by not being used for what it was originally intended.

Andy has been writing about music production and technology for 30 years having started out on Music Technology magazine back in 1992. He has edited the magazines Future Music, Keyboard Review, MusicTech and Computer Music, which he helped launch back in 1998. He owns way too many synthesizers.