Mike Mills talks life post-R.E.M., bass beginnings and essential gear

"We sort of had the zeitgeist"

Introduction

For many years one of the biggest rock bands on the planet, the much-loved R.E.M. called it a day in 2011. What’s bassist Mike Mills been up to since then? Bill Kopp finds out...

I grew up just outside of Atlanta, Georgia, so when R.E.M. got together in the nearby college town of Athens and started making noises in 1980, my friends and I thought of them as a local group.

[At their 22 April, 1985 gig] Michael Stipe spent the entire evening with his back to the audience. Still, a great show

We followed their rise in popularity with interest. I recall an episode a few months before the release of Fables Of The Reconstruction, R.E.M.’s third album, and the only one to have been recorded in the UK.

The band had just received an advance from their label and had purchased a brand-new live sound system. Wanting to work the bugs out in front of a sympathetic audience, they kicked off the Pre-Construction Tour with a free concert at Legion Field.

On 22 April, 1985, my friends and I made an hour-long road trip east to Athens, and watched as vocalist Michael Stipe spent the entire evening with his back to the audience. Still, a great show.

R.E.M. bassist Mike Mills and I first met about a year earlier at Atlanta’s now-legendary 688 Club, where we had both come to see Alex Chilton play. We chatted briefly, but that was the extent of our direct communication, until very recently. I did keep up with R.E.M., though.

In spring 1991 they released Out Of Time: that summer I was living and working in London, and was more than a bit amused to find that wherever I went, I heard Losing My Religion and the other tracks from the hit album. Here I was, on my first excursion off the North American continent, and all I heard was a band from back home.

In a nuthsell

A founding member of the group, Mills remained with the band until its amicable dissolution 30-plus years later. In addition to playing bass, Mills provided harmony, vocals and the occasional lead vocal, played keyboards, and - with guitarist Peter Buck - was a primary songwriter for the band.

Though he describes himself as ‘semi-retired’ since R.E.M.’s breakup, Mills has continued to busy himself with musical activity: he’s a member of indie-rock supergroup the Baseball Project, he’s been deeply involved in the ‘Big Star’s 3rd’ concerts series, and in late 2016 he released Concerto For Violin, Rock Band, And String Orchestra, a collaboration with lifelong friend and virtuoso violinist Robert McDuffie.

I had sort of resisted the P-Bass, because everybody played them. But then I found out why. It was because they’re the best, especially for live shows

Mills was born and raised in Macon, Georgia, 90 miles south of Athens. “Piano was my first instrument,” he says. “I first took lessons when I was 14, and then about a year later I started to teach myself bass.” By the age of 16 he was in a band with future R.E.M. drummer Bill Berry. “Bill and I were really solid,” Mills says. He played a Fender Jazz that belonged to his high school.

His mid-70s bass setup was modelled after that of a local hero, Allman Brothers Band bassist Berry Oakley. “I had two Fender Dual Showman reverb amps: one cabinet with two 12s and one cabinet with four tens,” he remembers. Although Mills is most often associated with the Rickenbacker 4001, he went through a series of basses before finding the Rick.

“I played a beat-up Hofner for a while,” he says. “Then I played an Ampeg Dan Armstrong clear acrylic bass, followed by a Fender Musicmaster, and then I found that ’71 Rick.”

The 4001 remained Mills’ instrument of choice “until one of the horseshoe pickups went out. We couldn’t find another one.” He got a factory-replacement pickup, but wasn’t happy with it, so he went through another series of basses - an Ibanez and Guild among them - before trying out a 1970 Fender Precision he calls Old Yeller after its original finish.

“I had sort of resisted the P-Bass,” he says, “because everybody played them. But then I found out why. It was because they’re the best, especially for live shows. They’re just so durable, and they don’t go out of tune. They sound fantastic, and they feel good to play.”

Eventually, though, Mills’ bass tech located a working vintage horseshoe pickup, and the 4001 was returned to active duty. It’s actually a 4001S with Rick-O-Sound stereo output. “But I’ve never used it,” laughs Mills. “We tried it, but it was more trouble than the sound was worth.”

Mills has made a point of avoiding bass guitars with more than four strings. “I can’t stand them,” he says, admitting that five-string basses “just confuse me.” His strings of choice are D’Addario nickelwounds, 45-100 gauge. “I’m a roundwound guy,” he says. “I like a lot of midrange, a lot more than most bass players. And I like a little buzz in there.”

Picky player

More often than not, Mills plays bass with a pick. “It depends on the song,” he says. “Not that I’m a funky bass player, but sometimes there’s a rhythmic thing you can get with your fingers that you can’t get with a pick. I’ve never really been an effects guy either. The only time I ever really used a pedal was on the 1995 Monster tour. I had a Big Muff distortion pedal that I would use on two or three songs.”

When recording, he says: “I just run it through the amp and record one direct, and then blend the two.” He adds that the sound coming out of his amp - often a Mesa/Boogie or an Ampeg SVT - was “usually so good that I didn’t mind if the producer wanted to blend in a little bit of the direct signal.”

I always enjoyed Chris Squire’s playing. I wasn’t a huge Yes fan, but I liked the way he played it melodically, like a guitar, and kind of up-front

One of the most distinctive qualities of the R.E.M. sound was the jangling guitar of Peter Buck. Playing bass behind that style - and along with what Mills calls Berry’s ‘orchestral’ drumming - meant that Mills often played in an active, melodic fashion with R.E.M. He names Berry Oakley as a major influence upon his style.

“I hate to be so obvious, but Paul McCartney was a big influence, too - and I always enjoyed Chris Squire’s playing. I wasn’t a huge Yes fan, but I liked the way he played it melodically, like a guitar, and kind of up-front.”

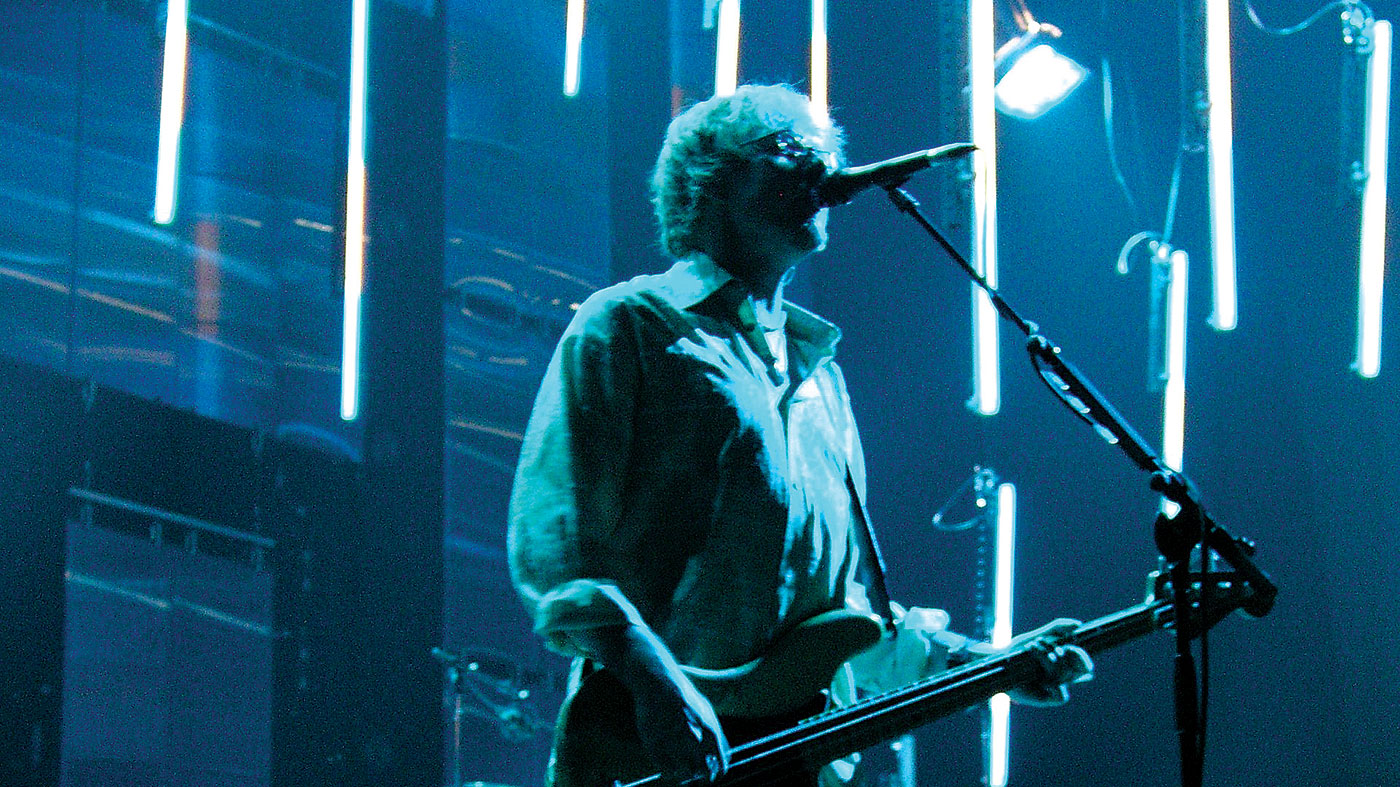

In his post-R.E.M. years, Mills has been most often seen onstage playing his trusty black Rickenbacker 4001. He’s used it on tours with the Baseball Project, and on his recent tour fronting the hybrid rock band/orchestra. For the latter, he’s part of a four-piece rock ensemble out in front of a 15-piece string section.

Regarding his next move, Mills is circumspect. “I have no idea what’s in the future,” he says, allowing that some things are likely. “There might be a few more Big Star 3rd shows down the line. Hopefully the Baseball Project will do another record soon, and I think there will be some more Concerto shows with various symphonies around the world.”

Most recently, Mills has been doing interviews in connection with the 25th anniversary expanded reissue of Out Of Time. That got him thinking about why the band was as successful as it was.

“What set R.E.M. off and apart was that we didn’t want to do things in a traditional way,” he says. “And we sort of had the zeitgeist.” That’s an understatement. Hats off, that man.