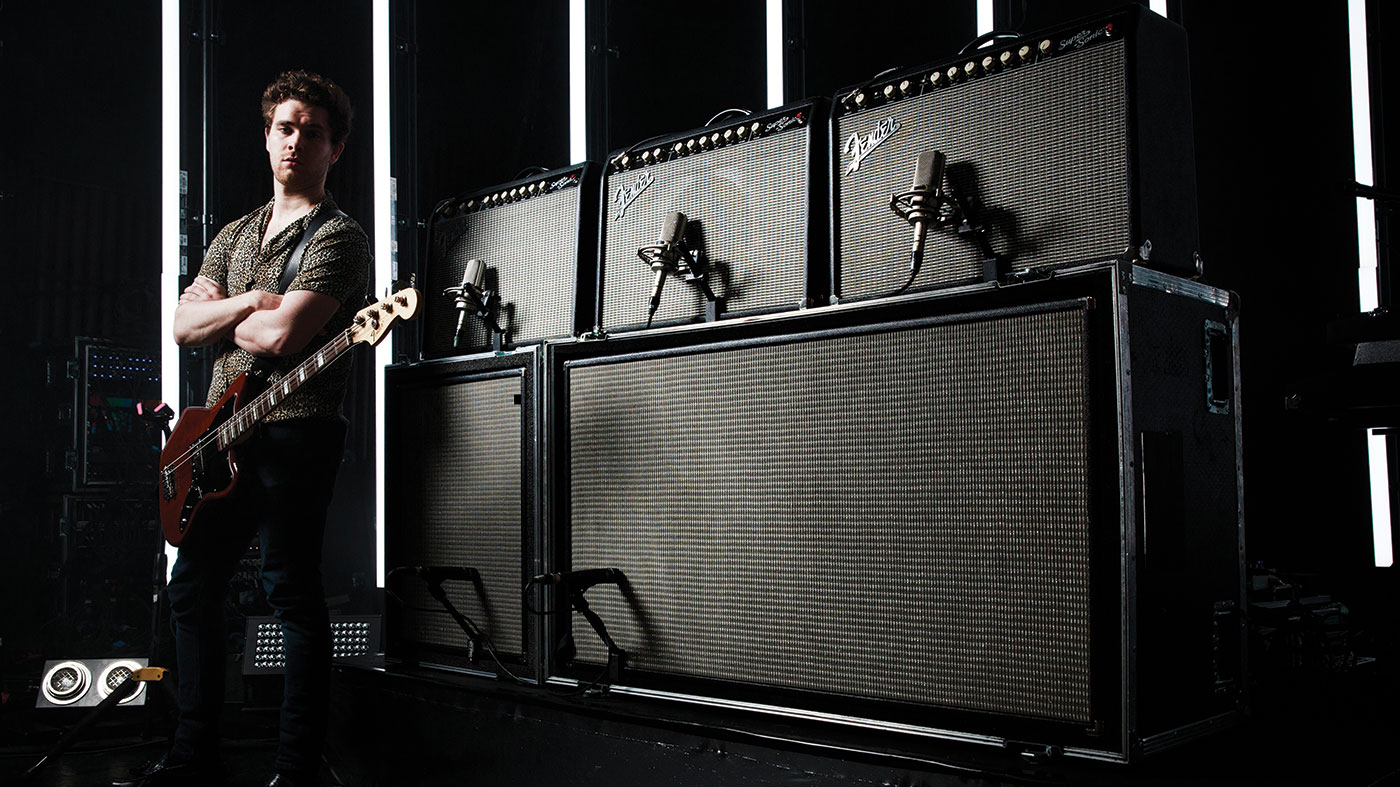

Mike Kerr talks Royal Blood's meteoric rise, his elusive bass rig and How Did We Get So Dark?

"You don’t get to decide whether you’re successful or not"

Introduction

Royal Blood are the coolest band in Britain - and unlike previous holders of that title, they do it all with bass and drums. Frontman Mike Kerr tells Joel McIver the unlikely story of his rise to glory with four strings, two amps and a mysterious signal chain…

“As soon as our first record came out, it went mental,” exhales Mike Kerr in evident disbelief, when we ask him if he can pinpoint the moment when Royal Blood’s sudden ascent to the public eye began.

The rock world reacted with massive enthusiasm to the band’s combination of catchy choruses, Zep'-style riffs and keen songwriting dynamics

We’re in the catering area at Newcastle’s O2 Academy and he’s chowing down on a bowl of curious green soup, but even though he’s focused on the task of getting his lunch down, he’s clearly still blown away by how fast his band have risen up the ranks.

As well he might be. Royal Blood, a duo formed by Kerr and drummer Ben Thatcher in Brighton just four years ago, released their debut, self-titled album a year later. The rock world reacted with massive enthusiasm to the band’s combination of catchy choruses, Led Zeppelin-style riffs and keen songwriting dynamics.

Royal Blood bassist Mike Kerr: my top five tips for drummers

A slew of industry awards and festival appearances followed, plus innumerable magazine covers, and by the time Royal Blood’s new album How Did We Get So Dark? was released last month, Kerr and Thatcher had built a rabid international following.

That said, you’d never know Kerr was the hottest rock star this country has seen in years from our conversation backstage in the Toon. Slurping down his soup and suggesting that we find a quieter spot for our interview, he seems preternaturally relaxed, ready for any question we might throw at him.

That includes the $64,000 inquiry about the contents of his pedalboard, a long-time secret that every bass and guitar hack in the Western world has tried to prise out of him over the past few years. Since we’re here, we might as well have a crack at it too - but first, let’s find out what it’s like to live on Planet Royal Blood...

Growing pains

How come your band has got so huge in such a short time, Mike?

“I honestly don’t know. Outsiders have theories about it. At the time we came out, we were probably the only rock band that were writing pop tunes. Maybe people were psyched that there were two of us, I don’t know... It’s hard to tell, really. It’s a mixture of being ready for it and being in the right place at the right time.

I used to play keyboards through loads of amps and pedals, so I just plugged a bass in and started messing around

“It must be something to do with the songs being good. I think the songwriting is what we value the most, really. That’s the most important thing to us.”

How did the idea of a bass and drum duo, with the bass also playing the guitar parts, come about?

“I started playing bass because Ben had joined a punk band as a session drummer. They needed a bass player, and it was a bit of paid work, but I didn’t play the bass at the time, so they sent me the songs, and they were beginners’ kind of basslines. So I just picked a bass up. I was probably 21 at the time.”

How old are you now?

“I’m 26. I just made it up and blagged it. But before I played bass I used to play keyboards through loads of amps and pedals and made these mad keyboard sounds through all the equipment I had, so I just plugged a bass in and started messing around with that. And then suddenly I started making this really big sound with guitar amps and bass amps.

“That got me really excited about playing the bass. I didn’t really have any intention of playing bass... I felt more like a guitarist. I’ve got this theory that all bass players want to be guitarists, really. Haha!”

Where did the idea of splitting the signal into guitar and bass amps come from?

I’ve always had a fascination with using more than one amplifier... just putting one at the other side of the room suddenly felt 3D

“I’ve always had a fascination with using more than one amplifier. The first time I played keys in a band, I used to play the basslines, because we didn’t have a bass player, and I got really into using two amps and realising what a big tone you could make. It was really powerful.

“Even just putting one amplifier at the other side of the room and switching between the two suddenly felt 3D, as if there was more than one person in the room. I’ve always done that, so when it came to the bass, I worked out that you could sound like three people just by turning an amplifier on and off.”

So what came first, the sounds you could make with an instrument, or the choice of instrument itself?

“I got excited about the sound first. That made me play in a certain way. I think if you plug a new pedal in, it makes you play differently. You play in a completely different style to how you would usually, because you’re adapting to a sound. When a new sound comes out I play bass in a completely different way. It’s the same when I want to write a new riff or a song idea: I pick up a new bass or plug into a different amp. It’ll just make you do something unpredictable.”

Six vs four

Did you play guitar before bass?

“Well, there was always a guitar in the house and I could play a few chords here and there.”

So, playing devil’s advocate for a minute, why not play guitar instead of bass and create the bass parts with an octave pedal, like the White Stripes did?

I don’t think it’s achievable with a guitar. It’s harder to fabricate a bottom end than it is to fabricate a top end

“I don’t think it’s achievable with a guitar. With all the two-pieces that are fronted by a guitar, I just felt that the bottom end wasn’t as good, because it’s harder to fabricate a bottom end than it is to fabricate a top end. With true sub bass, there’s something real, and starting with the bass, I had that bit covered - and by the time I emulate the top end, fuzz it and put it through guitar amps, it sounds great.”

You used to do all this with fairly affordable gear, correct?

“People buy an amazing vintage guitar that costs loads of money, and they plug into an amazing amp with all these tubes, but if you’ve got a pedal that’s designed to sound fucked up between them, then you don’t need that stuff at either end. So I figured it didn’t matter as much.”

Are you happy to discuss your pedalboard, or is that still classified?

“To be honest with you, it’s got to the point where even I don’t know what’s going on any more! There’s a few key things that I keep close to my chest, but the principle of the sound isn’t really a secret any more. I use octave pedals and guitar amps. It’s more like the routing of everything [which is secret] and a few things on the way that are sort of taking [the pedalboard] from being budget to gourmet, ha ha! There’s a few things on the way that just make it tidier.”

So are you going to tell us what’s in there?

Everyone knows I use an Electro-Harmonix POG 2 and some pedals for pitch-bending. It’s all about continually refining my sound

“Not really, no, but everyone knows I use an Electro-Harmonix POG 2 and some pedals for pitch-bending. It’s all about continually refining my sound. It’s always evolving and hopefully progressing.”

In what way?

“I’d just say there’s more sounds. I used to have one sound on the first album, whereas on this new album the whole rig has a new configuration on every song. It feels like a step forward.”

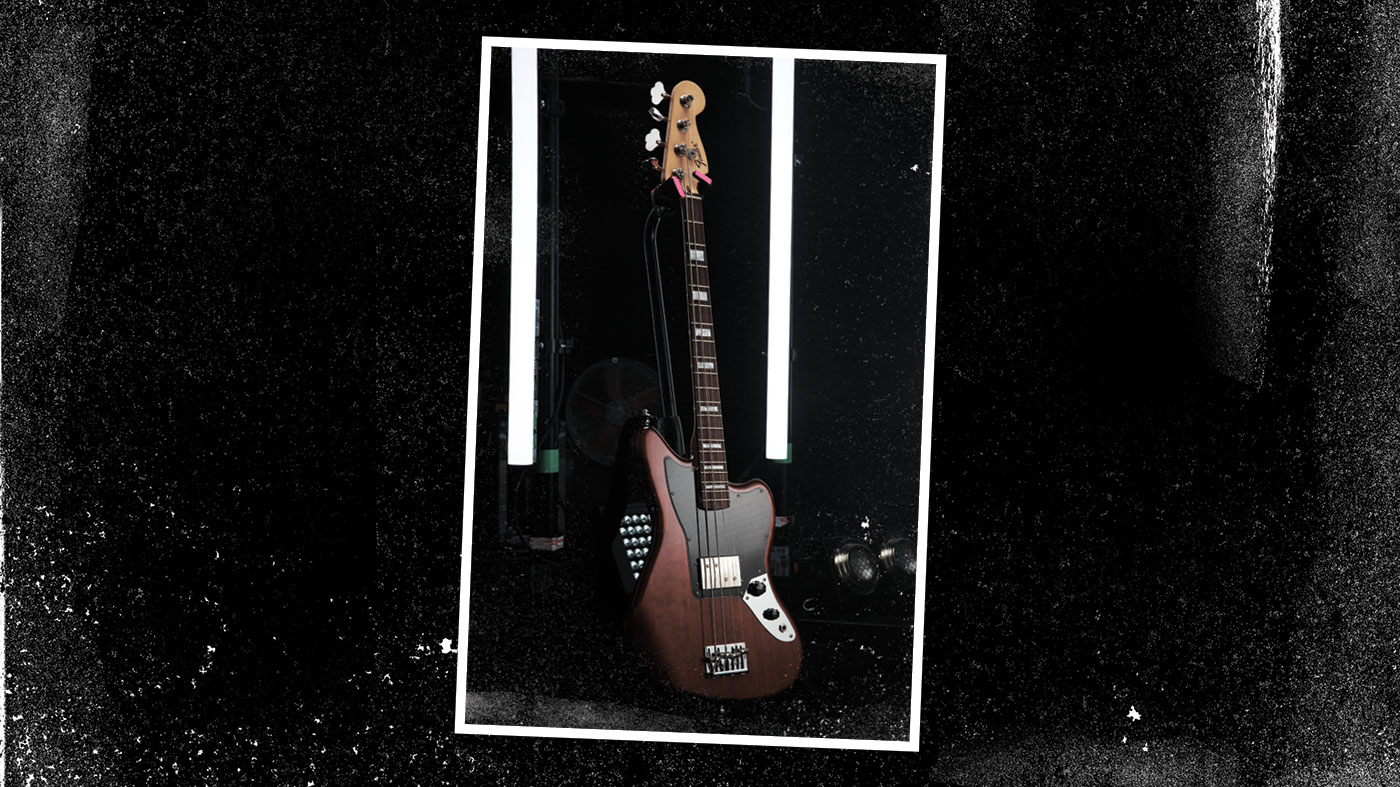

You used Gretsch basses for ages, but you’re now playing Fenders. Why the switch?

“Originally I used short-scale Gretsch Junior Jets. That’s how the Royal Blood sound started, on them. It’s a really cheap bass, 300 quid new. Eventually I was approached by [Gretsch’s owners] Fender, who realised that I was using all Fender amps and walking on stage with their Gretsch guitars.

“They were very nice: they said, ‘Is there anything we can do?’ and we got talking. They made me this über-Jaguar with a humbucker which I really like. They’re just tiny, and they feel like a guitar. As soon as I played one of them I was like, ‘There’s no going back’.”

Jag-style

Does it have the microswitches that the original Jaguars had?

“No, it literally just has one pickup, tone and volume. Just one output. I also use Fender Starcasters for certain songs. We have a new tune in B standard, so I need a bass that’s going to take that low tuning.”

Do you play five-strings?

“I’ve never gone there. We just tune down. There is one bass I have for the song Hook, Line And Sinker that has two guitar strings and two bass strings on it, just to get more reach on the scale. I always think of it as if you were sat at a piano, bass is the lower two octaves and your right hand is two octaves up, and is more extreme.”

What gauge are the guitar strings?

“I’ve no idea. They’re the top two strings of a guitar. It really screams. I’m not the first person to do that, but it’s a cool little trick if you want to find something different and amuse yourself a bit by putting the wrong strings on.”

You have a custom Manson bass, too.

“I do, but I don’t use it. There was a song I was working on at the time, and I worked out that I needed to make a certain guitar sound using a bass with guitar strings, but I ended up not using the song. So I have this amazing bass for no reason! It’s really, really good.”

So is the Jaguar your go-to bass?

I like to play open riffs, so if I want to change the key of a song I just throw the whole thing down or up

“Yes. The whole of the new album was done on those, apart from one song. I had them in lots of different tunings. Well, they’re all standard tunings, but I like to play open riffs, so if I want to change the key of a song I just throw the whole thing down or up.”

Presumably that makes singing across the riffs easier.

“Yes, exactly. I think you’ve just got to do it really slowly and practise. All of it is hard at first, but after a couple of shows it feels easier and easier. I had to concentrate a lot on these new songs.”

How many basses do you take on the road?

“Seven, in different tunings from B to F.”

What amps do you use?

“They’re all Fender: a Supersonic and a Bassman.”

Do you take a spare pedalboard with you?

“A few key spare pedals. Everything has a contingency plan. The way the pedalboard is set up now, it’s a lot safer. If one pedal goes down, the whole thing doesn’t go down, whereas before it was all one big chain.”

Complexity

The songs on How Did We Get So Dark? sound more complex than the older stuff.

“Yeah, but also, the way I wrote this time was I wrote the bassline and then I wrote the vocal part, so when we recorded the songs I’d never done them at the same time before. Suddenly I was like, ‘Shit, how am I going to do that?’ But it makes it interesting, and it means you’re at the peak of your ability as well. Even beyond your ability. You don’t even know if you can do it yet.”

Is it stressful playing a tricky bass part and singing a part over it?

“Not if I know it’s possible. I’d stress out if I knew it was impossible, or if I was overdubbing things that I couldn’t do.”

What’s the toughest Royal Blood bass part?

“There’s one song on the new album that I’ve only just learned. It’s taken three months. It’s the end of the song How Did We Get So Dark? It’s like a Rubik’s cube! I don’t have a musical explanation for it, but it’s a mantra lyric over a riff that’s constantly evolving. I just go into a daze and do it.”

Is there more pressure on stage because there’s only you and a drummer there?

“I guess so, yeah, but the rig sounds so good and so loud that I forget that there’s only two of us. It’s like being on your own in a sports car.”

How do you connect with a big crowd from the stage?

I think [with big audiences] it’s about engaging with them in a way that makes it feel like a smaller room

“I’m still working that out, but after watching the Foo Fighters play, I think it’s about engaging with them in a way that makes it feel like a smaller room than it is. Sometimes you have to physically bridge the gap between the stage and the audience. But once the lights are on and the songs are going, it feels pretty good.”

Which other bass players do you like?

“There’s Nick O’Malley of the Arctic Monkeys. I like his style of playing. I like bass players who go unnoticed: people who actually serve the song and don’t feel the need to draw all the attention to themselves. When you tune in, you realise how smart all of their parts are, and how musical the parts are, rather than being showy.

“I like all the basslines in Queens Of The Stone Age’s tunes, too. They enhance the grooves and change the whole feel of the melodies. It’s really smart bass playing.”

Riffs, rhythm and wrong-doing

Do you always play with a pick?

“I played fingerstyle when I first started, but the nature of how I play is guitar, really, so I need that bite for that classic guitar feel.”

Do you play slap bass?

“No. I would like to be able to. It probably wouldn’t have a place in our music, but I’d like to learn anyway. It looks fun.”

What advice do you have for aspiring bassists?

There’s no wrong way of doing anything. If anything, if you’re doing something wrong, you’re onto something

“Have fun. Nothing is important unless it’s fun, and if it’s fun, the rest will come naturally. Find a way of doing things that is enjoyable: there’s no wrong way of doing anything. If anything, if you’re doing something wrong, you’re onto something.

“Also, it’s important to listen to all types of music. It’s the only way to be forward-thinking and corrupt your genre, and the only way to do that is to bring in elements of other genres and break some rules. Listening to hip-hop and R&B really affects the beats in a lot of our tunes more than people might realise.

Talking of which, you and Ben must have a pretty close musical bond, as a rhythm section that is also the whole band.

“Where I would lay down a riff, any other drummer would come in with a classic rock beat, whereas Ben won’t even play any cymbals - he’ll go straight to the toms and keep it sparse with a big beat and a hiphop beat. Removing cymbals makes things sound twice as heavy.

“We juxtapose against each other too, so if Ben’s doing a really big rock beat, I think, ‘How do I fuck that up?’ If I just rock out with the drums, everyone’s heard that before.”

How do you write new riffs?

“I try not to look at the fretboard sometimes, because you know where everything is. You know what it will sound like if you go to a certain place. That doesn’t seem very creative.

“Sometimes I put all the strings out of tune, or I just try and write it all on one string. I always try to confuse myself a little bit, so I’ll follow my ear rather than following what I know.”

Pacifier

Do you write songs on the road?

“I write a lot of my riffs when I’m drunk and I sing into my iPhone. The next day I’ll sift through the ideas and when you translate them, they’re great. If you think of a riff, it’s usually cooler than if you sit and write one.”

What defines a good riff?

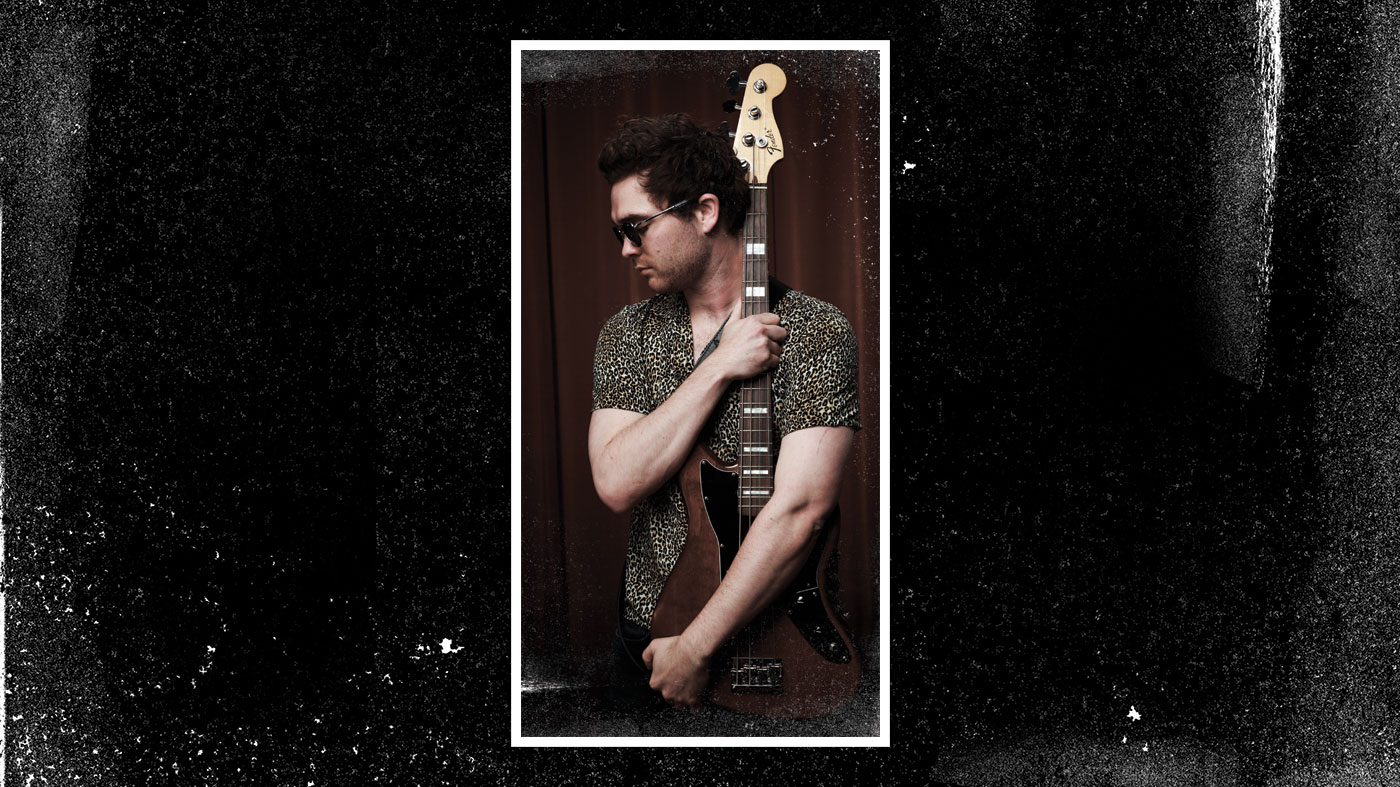

I’m always playing, because I like it. I feel more comfortable holding a bass. It’s like a dummy or something...

“To me, it’s more impressive to write something which people wish they wrote and which is easy, rather than something that they’ll never be able to play because it’s too hard. Like Seven Nation Army by the White Stripes. That could literally be the first thing you might teach someone to play, yet it’s one of the most iconic riffs of our generation. It’s international and it’s sung in stadiums all round the world. I’d rather write something like that than some progressive shred.”

Is practice important for you?

“I never sit down and practise, but I’m always playing, because I like it. I feel more comfortable holding a bass. It’s like a dummy or something... but I never sit and do scales, or anything like that. I’m always looking for the next riff or the next song idea. Maybe I should learn more scales, I might get more ideas. But the whole idea is that I want to know less.”

Does life on the road suit you?

I always wanted to play music in front of people, but you don’t really get to decide whether you’re successful or not

“We love it, and we enjoy it, but I won’t see home now for two years. My family are happy that I have a proper job... well, not a proper job, but you know what I mean. Before that I worked in restaurant kitchens and Ben worked in bars. I always wanted to play music in front of people, but you don’t really get to decide whether you’re successful or not: that’s something that happens to you.”

Which brings us back to our first question: has there been a secret to Royal Blood’s success?

“No. When we started jamming together in 2013, if we’d wanted to be successful we wouldn’t have formed a two-piece dirty rock ’n’ roll band, we would have tried to emulate someone who was experiencing success. We were just doing what we wanted to do.”

Your life must be rather surreal.

“Yeah, it’s mad. Every morning, I walk into the venue and I think, ‘Why are people coming?’”

How Did We Get So Dark? is out now on Warners. Royal Blood play a UK arena tour in October and November.