"This track is an undeniable banger, but it’s also extremely weird": The borrowed hooks and unstable grooves behind Michael Jackson's Wanna Be Startin' Somethin'

We put one of MJ's best-loved tunes under the musical microscope and explore the unlikely origins of its iconic hook

It’s always gratifying to find out that the kids these days like the music that I like. The week that I started writing this, a few different students of mine brought up Wanna Be Startin' Somethin' independently of each other. I guess the song is in the air. It’s my favorite Michael Jackson original, and one of my favorite songs of the 1980s across the board.

This track is an undeniable banger, one of Michael’s most reliable dance-floor fillers, but it’s also extremely weird. (All of Michael’s best songs are.) Its most memorable hook is an African-sounding phrase that no one knows the meaning of. We will get to that below, but first let’s examine the rest of the song.

Michael wrote Wanna Be Startin' Somethin' for his sister La Toya to express the conflicts she was having with her sisters-in-law. Both Michael and La Toya performed it, but Michael’s version is the famous one.

It was the fourth consecutive single from Thriller to hit the top ten on the Billboard Hot 100. It’s one of four songs on the album that Michael is credited with writing - the other three are Billie Jean, Beat It, and The Girl Is Mine with Paul McCartney.

You can hear Michael’s home demo below; aside from the unfinished lyrics, it sounds remarkably complete.

Michael programmed the beat on a Linn LM-1 drum computer, a drum machine that came to be most closely associated with his arch-rival Prince. In addition to Michael’s vocals and drum machine programming, the released version of the song features David Williams on guitar, Louis “Thunder-Thumbs” Johnson on bass, and Paulinho da Costa plays percussion. There are three keyboard players: Greg Phillinganes, Michael Boddicker and Bill Wolfer (who also played the haunting intro chords in “Billie Jean”.).

All of these guys are top-flight session musicians who you have heard on a million other songs. There’s a horn section consisting of trumpet, flugelhorn, trombone, saxophone and flute. The six backing vocalists include Oren Waters, who also sang the Jeffersons theme song, and James Ingram, who sang Somewhere Out There from the American Tail soundtrack. Finally, Michael, Nelson Hayes and Steven Ray are credited with “bathroom stomp board”.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Harmonically, Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ could not be simpler. All the excitement comes from the rhythm

Harmonically, Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ could not be simpler. The whole thing is in E Mixolydian mode, which is like E major but with a flatted seventh (D instead of D-sharp.) The bassline consists entirely of the notes D, E and B. The chords, when they are present, are a simple loop: a bar of D alternating with a bar of E. All the excitement of the song comes from the rhythm, which is wildly unstable for a dance pop song. To understand why, we need to do a little math.

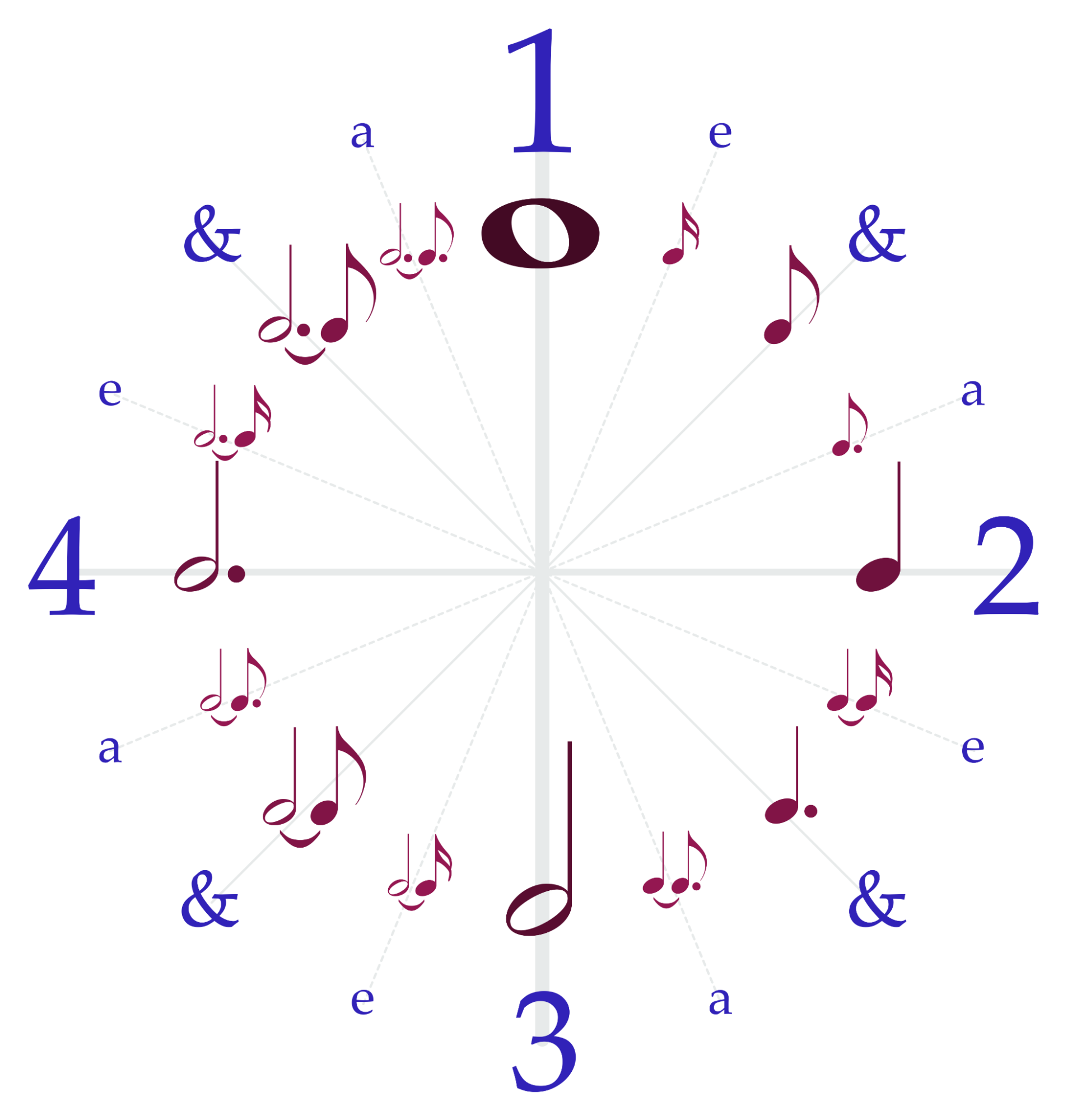

Think of a bar of 4/4 time, the “one, two, three, four” count you can do along with most Anglo-American pop songs, including Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’. Each of those numbers is a beat, and each beat is a quarter note long (that is, each one occupies a quarter of the bar.) You can subdivide each of the beats into halves (eighth notes) or quarters (sixteenth notes).

Some of these beats and subdivisions are stronger than others. You naively expect drum hits and other rhythmic accents to fall on the stronger beats or subdivisions. When accents fall on weak beats or subdivisions, it defies your expectation, creating a pleasurably surprising effect called syncopation. The key to creating a good dance beat is to balance predictable and syncopated rhythms.

So how do you know which beats and subdivisions are strong and which are weak? This is where the math comes in. The more times you have to divide the bar in half to get to a beat or subdivision, the weaker it is.

The strongest beat is beat one, the downbeat. Pop songs accent the downbeat just about all of the time, and the accented downbeat is how you orient yourself to everything else. The next strongest beat is beat three, halfway through the bar. It’s so strong that it almost acts like a downbeat itself. If you divide the bar in half again, you get beats two and four, the backbeats, which are weaker.

Every kind of Black American music of the past hundred years has had snare drums, handclaps or sharp guitar strums accenting the backbeats, and Wanna Be Startin’ Something’ is no exception. The accented backbeat is the rhythmic commonality that unites ragtime, blues, country, jazz, R&B, rock, funk, hip-hop, and every kind of electronic dance music.

The accented backbeat is the rhythmic commonality that unites ragtime, blues, country, jazz, R&B, rock, funk, hip-hop, and every kind of electronic dance music

Accenting the backbeats is a pretty tame syncopation; we have come to expect it, so it’s hardly surprising at this point. You can make cooler rhythms by dividing the beats in half and accenting the eighth note offbeats. For maximum syncopation, you can subdivide yet again and accent the sixteenth note offbeats in between the eighth notes. This is how you create the sophisticated grooves you hear in the music of James Brown, Prince, and of course, Michael Jackson.

With all of that knowledge in mind, let’s take a look at the drums and bassline of Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’. If you try to count or clap along, you may have a hard time locating the downbeat. This is not because of any deficiency in your rhythmic sense. It’s because the kick drum and bass never play on the downbeat. Instead, they accent the sixteenth note subdivision immediately before and after the downbeat.

This is wildly unconventional! I can’t think of a single other song from the American pop mainstream that does it. There’s a hi-hat on the downbeat, and the vocal melody starts there too, but these elements can’t overcome the instability in the groove’s foundation. Everything else in the track gets its energy from that instability.

In structural terms, a groove is a small musical cell that repeats indefinitely. A song is a hierarchical organization of smaller cells that form a linear sequence with a beginning, middle and end

The musicologist Anne Danielsen studies funk, and she draws a distinction between songs and grooves. Yesterday by the Beatles is an example of a song. The Payback by James Brown is an example of a groove. In structural terms, a groove is a small musical cell that repeats indefinitely. A song is a hierarchical organization of smaller cells that form a linear sequence with a beginning, middle and end.

Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ is more of a groove than a song. It has an order to it, and the sections have different melodies, but the background parts are one continuous rhythmic loop, with layers entering and exiting but nothing really changing or progressing. The track could be two minutes long, or twenty minutes, or two hours, and it would work just as well.

American popular music is a blend of songs and grooves. To grossly oversimplify: the song-ier parts mostly descend from Europe, and the groove-ier parts mostly descend from Africa. If you listen to a groove expecting large-scale structure, then you miss out on all the rich structure present within the repeating cells. This kind of listening requires practice. I was listening to a Babatunde Olatunji recording in college, and my roommate complained that he didn’t like it because there was no “beat” and no “melody.” It was nothing but drumming and singing! He meant that he didn’t like the absence of linear structure.

Pop and dance music are groove vehicles. Very often when people think they like a pop song, it’s because they really like the groove underneath it. The charts have always been full of songs with silly or meaningless lyrics that people (rightly) love because they have strong grooves.

The KLF explain this concept in their guide to writing a number one hit: "The club D.J. (like his forerunner the dance band leader of the thirties, forties and fifties) realises that the most important thing is keeping the dance floor full and the thing that keeps the dancers dancing now (as it was then) is the music with its underpinning groove factor. Singing throughout has always just provided a distraction from the main event – what is happening on the dance floor and not on the stage."

Music that’s meant to be listened to alone can be lyrics-oriented and built around a vocal sound. But social music needs to center on the beat.

Given how memorable the ending chant is, it’s easy to forget how weird the rest of the lyrics to Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ are

Given how memorable the ending chant is, it’s easy to forget how weird the rest of the lyrics to Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ are. They are mostly in a confrontational second person. The first words you hear are the main hook, and they are threatening a fight. This conflict is a painful one, like thunder, and there is no escape from it, because it’s too high to get over and too low to get under. The whole situation is dire: the baby has a fever and a breakdown, and someone is always trying to start her crying. Your tongue is a razor, and you are treacherous, cunning, and declining.

On the bridge, Michael repeatedly calls you a vegetable, reminds you that they (whoever they are) hate you, and that you’re just a buffet that they eat off of. Billie Jean makes an inexplicable appearance. You are warned not to have a baby that you can’t feed, and in spite of your hustling, stealing, and lying, the baby is slowly dying. That is a lot of anger, regret and paranoia for a fun dance song.

At the end, the song’s mood abruptly shifts to become uplifting and inspirational:

Lift your head up high and scream out to the world

I know I am someone and let the truth unfurl

No one can hurt you now, because you know what's true

Yes, I believe in me so you believe in you, help me sing it

And then comes the iconic ending, the “Ma ma se ma ma sa ma ma coo sa” chant. It takes up more than a minute of the song, and I have heard DJs extend it far longer than that. But what does it mean? It may surprise you, as it surprised me, to learn that it doesn’t literally mean anything in particular.

Michael is loosely approximating the main hook from Soul Makossa, a 1972 disco classic by the Cameroonian saxophonist Manu Dibango. (Michael probably drew on the Soul Makossa beat for his drum machine pattern too.)

But just because Michael didn’t know what Dibango’s chant means, surely Dibango meant something by it? Again, no, not really. Dibango is playfully scatting around with the word makossa. The Cameroonian linguist George Echu explains that makossa is a Duala word meaning “I dance”. On the Language Log blog, Ben Zimmer says that makossa derives from the Duala word kosa, which means to peel a fruit or vegetable, and that the twisting and shaking motion inspired the dance.

Dibango wrote Soul Makossa as the B-side to Mouvement Ewondo, a praise song for the Cameroonian football team on the occasion of the 1972 Tropics Cup.

In his autobiography, Three Kilos of Coffee, Dibango recalls:

"On one side of the 45 I recorded the hymn [praise song]; on the other I recorded Soul Makossa, written using a traditional makossa rhythm with a little soul thrown in. In my Douala neighborhood, at my parents’ house, I rehearsed this second piece. The house had no air-conditioning, and the windows were wide open. All the kids flocked around. Hearing me rehearse, they fell over laughing. Unbelievable — how on earth had I concocted that mishmash? Poor makossa really took a blow.

"My father was astonished: “Can’t you pronounce ‘makossa’ like everyone else? You stutter: ‘mamako mamasa.’ You think they’re going to accept that in Yaoundé?” The Cup organizing committee reacted the same way. The march on side one they found 'impeccable.' But the other side… 'Really, Manu has gone nuts. What possesses him to stutter like that?'"

Michael’s chant is not identical to Dibango’s. The most obvious difference is in the syllables, but there are musical differences too

The New York DJ and party promoter David Mancuso heard Soul Makossa and put it into heavy rotation at his loft parties. The song became an underground hit, especially when it started getting airplay on WBLS. The few copies floating around New York were quickly snapped up by other DJs. Several bands rushed out their own covers to fill the gap, most notably Baba Olatunji and the Lafayette Afro-Rock Band. Their versions are fun, but nowhere near as funky as the original. Finally, Atlantic Records released Manu Dibango's version on one of their sub-labels, and it cracked the Billboard Top 40 in 1973.

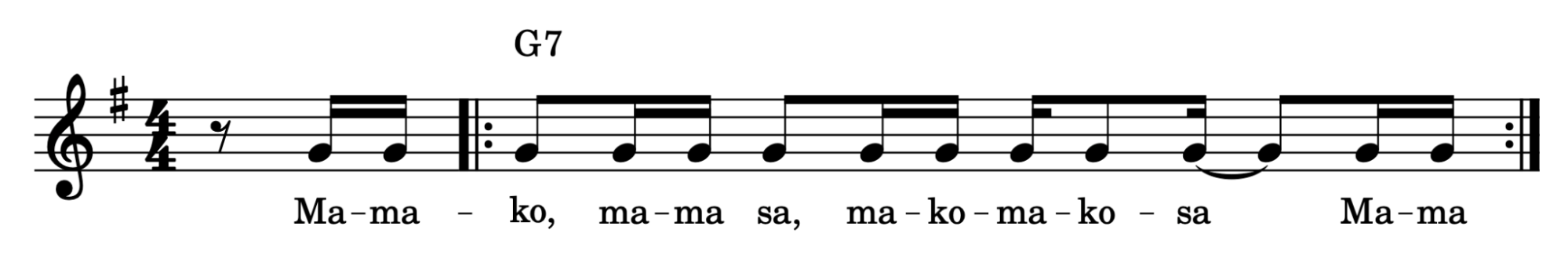

Manu Dibango sued Michael over his interpolation and got an out-of-court settlement of one million French francs. I can understand why he filed suit, but it’s worth pointing out that Michael’s chant is not identical to Dibango’s. The most obvious difference is in the syllables, but there are musical differences too. Manu Dibango’s chant is a one-bar phrase sung/chanted entirely on the note G, over an unchanging G7 chord.

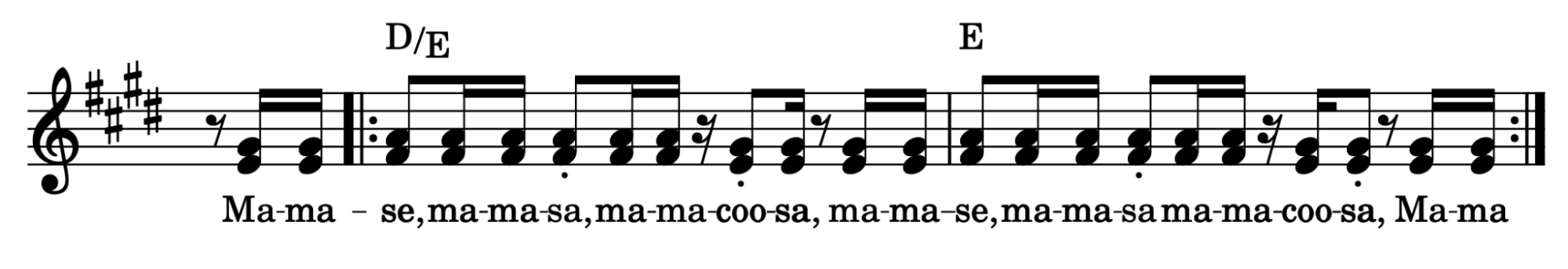

Michael Jackson’s chant is a two-bar phrase with a call and response structure–the “coo-sa” is accented differently in the first and second bars. He sings a two-note melody harmonized in thirds over that alternating D and E chord progression. He also adds a little more syncopation. I’d say that Michael’s chant is more of an adaptation than a direct theft.

Dibango’s chant is quoted and referenced in a thousand rap and R&B songs, as is Michael’s version of it. I especially love Startin’ Somethin’ by Lord Tariq and Peter Gunz from 1998, which interpolates many elements of Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’.

Rihanna had a hit of her own with Don’t Stop The Music, which samples Michael directly.

The chant is not the only culturally impactful part of Soul Makossa. Beyoncé quotes Manu Dibango’s horns in Deja Vu from HOMECOMING Live.

By the way, Manu Dibango’s career is so much bigger than Soul Makossa. I highly recommend his 1985 album Electric Africa, produced by Bill Laswell and featuring Herbie Hancock.

Soul Makossa must have been meaningful to Michael; he didn’t base any of his other songs on quotes or interpolations. But what did it mean to him? Nelson George gives a possible explanation in his book Thriller: The Musical Life Of Michael Jackson. The Jackson 5 traveled Senegal in 1973, and the experience had a profound effect on teenaged Michael.

Soul Makossa must have been meaningful to Michael; he didn’t base any of his other songs on quotes or interpolations. But what did it mean to him?

George quotes him as saying, “I don’t want the blacks to ever forget that this is where we come from and where our music comes from. I want us to remember”. Michael Jackson’s racial identity is much too big a topic for this article, but suffice to say that it was complex. He did love Black music unreservedly, though, and maybe interpolating Soul Makossa was his way of connecting his own music back to its ancestral source. Maybe there would have been a way for Michael to celebrate that connection without appropriating Manu Dibango’s chant, but I am in no position to judge him.

Nelson George’s book also tells the story of a public dance party that Spike Lee threw in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park to celebrate Michael’s 51st birthday. I was one of the several thousand people at that party, and in spite of the rain, it was a great time. DJ Spinna played Michael’s songs and everybody danced. The party peaked with Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’, with the crowd doing the Makossa chant in unison for what felt like hours. Did the chant mean anything to us, or was it just an excuse for a large and wildly diverse crowd to dance and sing together? Maybe not, but maybe that’s all it needed to mean.

Ethan Hein has a PhD in music education from New York University. He teaches music education, technology, theory and songwriting at NYU, The New School, Montclair State University, and Western Illinois University. As a founding member of the NYU Music Experience Design Lab, Ethan has taken a leadership role in the development of online tools for music learning and expression, most notably the Groove Pizza. Together with Will Kuhn, he is the co-author of Electronic Music School: a Contemporary Approach to Teaching Musical Creativity, published in 2021 by Oxford University Press. Read his full CV here.