“You can almost hear The Beatles influence and the Led Zeppelin influence at the front of the song”: How Dave Mustaine channelled unlikely influences for Megdeth's Hangar 18

"These were songs that I took with me to that first band – didn’t get a chance to get them out in my second band – but my third one I did”

The front-to-back brilliance of Megadeth's 1990 classic Rust In Rust In Peace, was an unexpected artistic miracle.

Given the wreckage arising from the band’s late-80s drug issues, you’d have had more chance of throwing a stick of charcoal to a gorilla and getting a scale drawing of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man in return than Megadeth writing and recording a career-defining album. Megadeth were a shambles.

With trusted lieutenant, bassist and (back then) Owen Wilson look-alike Dave 'Junior' Ellefson by his side, guitarist and vocalist Dave Mustaine directed operations, but the pair of them had long-standing issues with cocaine, heroin and God knows what else that had seen Megadeth bail on a seven-date stadium tour with Iron Maiden. But everything that made Megadeth so exciting – Mustaine’s sneering polemic, hyperkinetic riffs etc – was about to coalesce in Rust In Peace, and it started with a changing of the guard.

Drummer Chuck Behler was on his way out as the touring cycle for So Far, So Good, So What neared conclusion. His tech, Nick Menza, had already filled in during soundcheck when Behler was AWOL. To paraphrase Gary Busey in Point Break, Menza was young, dumb and, er, full of ambition. Megadeth needed somebody like Menza, a dude whose excesses were restricted to piss and vinegar – and unshakable self-confidence. They needed a lead guitarist, too. Former guitarist Chris Poland had demoed four tracks for Rust In Peace but there was no chance of him rejoining. Then, from nowhere, enter Marty Friedman.

When he came into the studio – I had been sober – I felt I had lost grasp of my trade... I couldn’t believe he was that good

Dave Mustaine

“He was wearing vile shoes. The knees were ripped out of his pants,” Mustaine told US extreme music mag Decibel. Mustaine might not have cared for Friedman’s appearance and thought his name wasn’t metal enough, but he knew that he had found a player. Friedman’s name was already recognised in the pantheon of shred guitar after partnering Jason Becker in Cacophony. “I went back into the room and told him he got the gig, but he had to get his hair fixed and get some new clothes so that he didn’t look like a bum. He was an incredible musician. Very willing to do what it took. When he came into the studio – I had been sober – I felt I had lost grasp of my trade... I couldn’t believe he was that good.”

The contrast in styles between the exotic Friedman and the feral pentatonics of Mustaine was the most exciting dynamic in Megadeth’s Rust In Peace. Mustaine was adamant that rhythm parts were doubled, but Friedman let loose for the solos. Both players used Jacksons during the recording. Mustaine used a King V with a Kahler bridge, and his classic Seymour Duncan humbucker combo of a Jazz in the neck and SH-4 JB in the bridge. Friedman used the Jackson Kelly, it too fixed with a Kahler fixed bridge, with a single SH-4 in the bridge position. Mustaine used his Marshalls. Friedman used a variety of amps, most notably a Bogner Triple Giant.

Mustaine’s seemingly bottomless well of ambition, dug out from his perceived slights at his ejection from Metallica, could have been one of the reasons that he hired producer Mike Clink. Sure, Clink had worked with Michael Schenker and UFO, one of Mustaine’s heroes, but it was his success with Appetite For Destruction that sealed the deal. As it transpired, Clink left when Axl Rose came calling again, and Micajah Ryan finished the album.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Megadeth had put together a compendium of thrash metal jams that changed the game. And it was looked at as a game, a competition, an arms race between themselves, Slayer, Anthrax and Metallica. It seems preposterous, but the one-upmanship delivered an album with such knucklebenders as Tornado Of Souls, Five Magics, and the extraterrestrial panic of Hangar 18.

Conceptually, the track was sketched out by Menza, a perma-stoned alien nut – Friedman told Decibel “I thought he was out of his mind, rambling on about aliens and government conspiracies” – but Mustaine had written the music for Hangar 18 years before Megadeth were formed.

“I wrote a lot of songs when I was really young,” Mustaine told Total Guitar magazine's Ed Mitchell in 2010. “Rust In Peace... Polaris was written before I was in my first band, Panic. So was Mechanix. Hangar 18 was just another one of those songs, although it was actually under a different title. These were songs that I took with me to that first band – didn’t get a chance to get them out in my second band [Metallica] – but my third one [Megadeth] I did.”

The intro chord progression, familiar to anyone who can play the haunting clean part to Metallica’s The Call Of Ktulu [on which Mustaine is credited as a co-writer], sets the tension bar high; Hangar 18 might have been a fantasy skit on Roswell, Area 51 and various pop-culture alien tales, but it is also perhaps the purest expression of the tension within Megadeth. Not between each other, per se, but the tension and compulsion to create a record that would usurp anything their peers could come up with.

“You can almost hear The Beatles influence and the Led Zeppelin influence at the front of the song,” Mustaine told Total Guitar. “Then in the middle of the break when we go to the first extended solo section, it’s a very Spanish kind of part. Then the end solo, when the guitar duel takes over, it’s no holds barred, get the fuck out of the way!”

Good luck with that part. Mustaine should consider himself fortunate; he only had to compete with Friedman. To master Hangar 18 on guitar you’ve got to master Friedman and Mustaine.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

“A fully playable electro-mechanical synth voice that tracks the pitch of your playing in real time”: Gamechanger Audio unveils the Motor Pedal – a real synth pedal with a “multi-modal gas pedal”

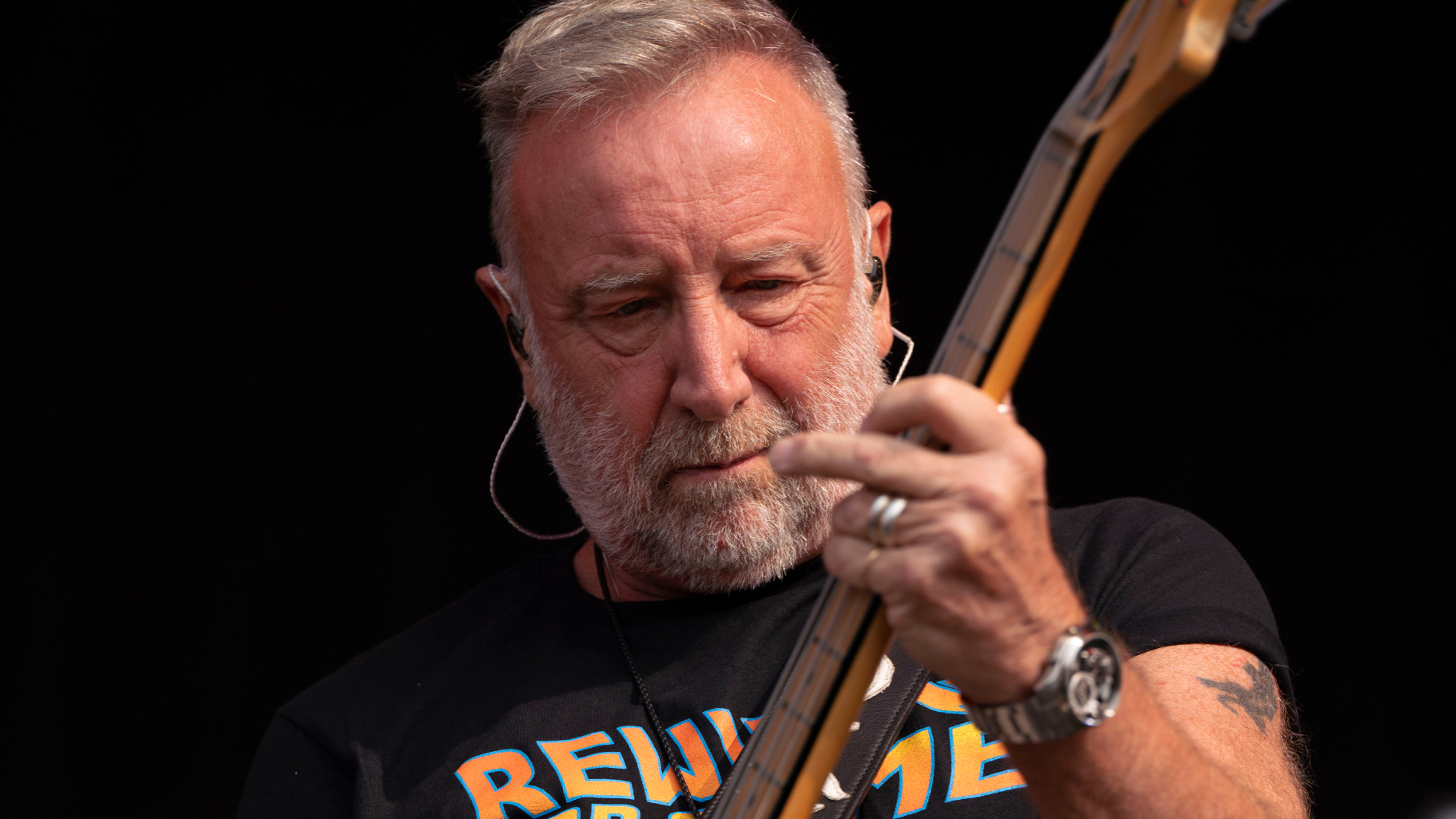

“I don’t think they’re New Order. They don’t sound anything like them”: Peter Hook takes aim at his estranged bandmates

![PRS Archon Classic and Mark Tremonti MT 15 v2: the newly redesigned tube amps offer a host of new features and tones, with the Alter Bridge guitarist's new lunchbox head [right] featuring the Overdrive channel from his MT 100 head, and there's a half-power switch, too.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/FD37q5pRLCQDhCpT8y94Zi.jpg)