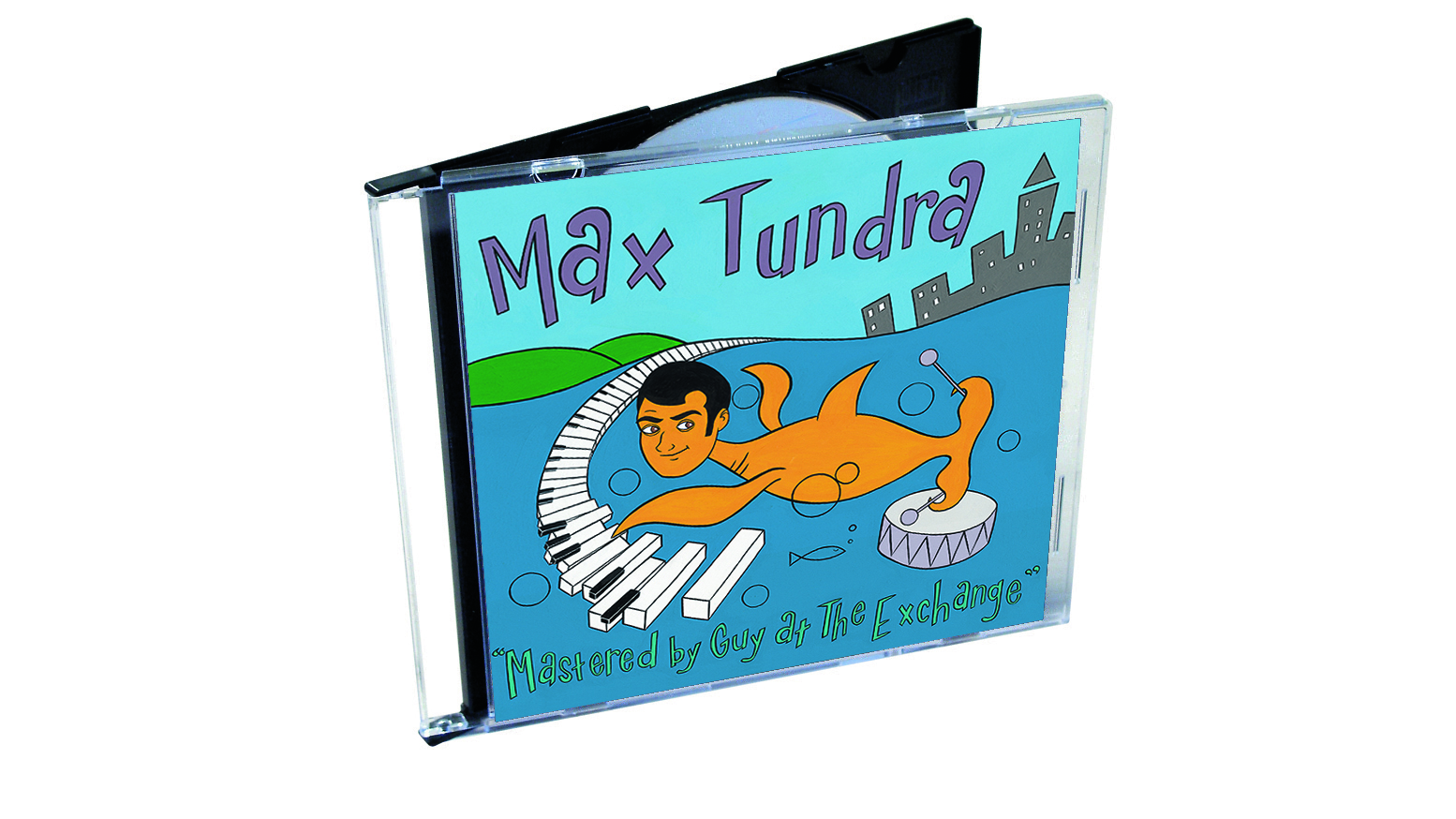

Classic album: Max Tundra on Mastered By Guy at The Exchange

The genre-defying producer on how he pieced together his sophomore album from a million shards of disco samples, time-stretched vocals, literary references, mutant disco and Game Boy bleeps

For the follow up to his category-defining instrumental debut, Some Best Friend You Turned Out To Be, Max Tundra wondered aloud what pop music should sound like.

During a glorious summer, with little else to bother him, he concluded that it should be made from a million shards of disco samples, layered and time-stretched vocals, in jokes, literary references, classic rock pomp, proto-dubstep drums, mutant disco, and Game Boy bleeps. His freaky findings would make up the meat of Mastered By Guy At The Exchange. An album of joyous noises and catchy, candy-land glitches and gear changes. All holding happy hands with digital diversions and loose and live instrumentation.

At the end of it, if it sort of sounds like anyone else, then I’ll try and start again

And as fun as it is to listen to, it must have been a waking nightmare to rack correctly on record shop shelves. You might settle into a track that opens with lo-fi rock, only for it wander off into reimagined disco territory. Then, as you get your head around a song about facial herpes medication, another one’s in Spanish. It’s music intended to amuse, confuse, delight and unsettle. Often in the same eight bars.

Max explains: “When I make a piece of music, it’s always like, ‘I want this not to be a genre’. So, every single time it’s like, ‘Oh, I’m not going to do a techno track’. Or, you know, a sort of old country track. There might be elements of both, or neither, of those. But, then at the end of it, if it sort of sounds like anyone else, then I’ll try and start again.”

As the album celebrates its 20th anniversary next month as part of a trilogy of reissues, it’s never felt so contemporary. The current crop of hyperpop artists like A.G. Cook, the late SOPHIE, and Charli XCX have all liberally spliced its DNA into their globe-smashing music, and more people are tracing that sound back to this one man and his Amiga.

“People always point out that this album heavily influenced that scene,” says Max. “And, I don’t want to blow my own trumpet, like I did on several tracks [laughs]. But, if they say I’m responsible for all that, then who am I to argue?”

“I recorded mainly at The Electric Smile, which was where I was living in Bristol at the time. The main workhorse was my Commodore Amiga 500, which I no longer have. Which was running a sequencer called MED. Just a tracker sequencer. So that would drive, basically, the Amiga. I just stuck a MIDI interface in the back and it would control my Akai S1000 sampler.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I had a Nord Lead 3, which I’ve still got in the attic. And then things like a Kurzweil PC2R, which is a sort of sound module, like a general MIDI sound module, with a really nice realistic orchestra and piano sounds. And then various little sort of toy synths and things.

“There’s a lot of ‘so-called’ real instruments in amongst the synths. I had guitars, cellos, a Fender Rhodes. Then the Roland VS-2400CD, and I had this [TL Audio] Fat Man compressor. It was a red box with a valve in it, and almost every single sound on the record went through that.”

Merman

“This was my ‘jazzy show tune’. I wanted to do something that was the antithesis of the boring, faceless, techno, laptop jockeys you get a lot of, you know? I was just thinking, ‘What’s the least likely sound to come out of that sort of setup?’ And it was this track.

“Most of the sounds came from the Kurzweil PC2R, and possibly a Yamaha QY20, which I had for a time. So, some of those general MIDI sounds and basically, fake trumpet, fake brass band, fake double bass, and things like that.

“And then it’s all sequenced with a kind of jazzy vocal on the top, where I’m bemoaning the downstairs neighbour playing really bad trance music [laughs].”

Mbgate

“The only vocal is from The Third Policeman by Flann O’Brien, which is my favourite book. The line is repeated atop this choppy disco background that comes out of a lo-fi rock intro.

“I spent a lot of time in the early 2000s just making these micro samples. And if you’ve ever worked with the [Akai] S1000, it’s painstakingly slow by today’s standards. Like, ‘Here’s this 20 second piece of library music. I want the synth stab at 3.5 seconds. I’ll just trim it to that. Set the start point, set the end point, press trim.’ And then it’d take 15 seconds to process just that cut. So, imagine, on that track, there would be 200 samples. And so you’re doing that every time. Luckily I didn’t have a day job.”

Lysine

“This track rolls out of the previous one. It starts on the major fourth, above the last trumpet chord. I’m always very sympathetic to what key something was in.

“It’s also the first song with Becky, my sister, singing about Lysine [medication] and cold sores.

“And for the instrumental break, you’ll hear an egg slicer. I sampled lots of different plucking sounds. There’s probably some other kind of kitchen-based item in there, too. And then it’s just mixed in with drum machine sounds, and other percussive elements.

“Oh, and a ticking noise. That’s a recording of a clock in the British Museum. It just felt like a nice event going there just to record this sound, then coming home and using it.”

Fuerte

“This is my own Spanish language track, and the sounds are done using the internal Amiga sound chip, Paula.

“Generally speaking, I would only use the Amiga for sequencing external hardware. But, on this one, I just wanted to get that 16-bit computer game-y sort of sound. So, it’s just pure Amiga, with a bit of reverb on top.

“In terms of the conception, like all the songs, it had a melody-first approach. Quite often I’d dream the melody, or think of it just before going to sleep. And if it’s still in my head in the morning, it’s a keeper. Which is quite scary, because you forget loads of stuff. I used to sing into a cassette-recording Walkman.”

“That’s lots and lots and lots of layered vocals from me and my sister. Like 20 passes of a vocal to get that crowd sound. There’s real violin, and real cello in the weird breakdown bit. And, probably, real drums.

“The bass is either a bass guitar, or a pitched down electric guitar. It might have even been the pitched down cello, being plucked like double bass. And that’s a very short track, less than a minute long. I was just trying to explore weird gaps between musical genres on this album.”

Cabasa

“This could easily have been broken down into three or four different tracks, but I wanted one where it was about the evolving of an idea.

“I like to see where I can go from a starting point, almost like an Exquisite Corpse. Like, ‘There’s the head, and the body is completely different than the feet. No, they’re not feet, they’re weird tails’ [laughs].

“It has a very sort of anonymous techno-sounding thing, and then this weird sort of slightly triplet-y, offbeat rhythm coming in. And then there’s some piano, and then it ends up in that almost Ben Folds Five territory, right at the end. Which was just a sort of test to see if people were sticking around, I guess.

“Then everything would have gone through a Fat Man compressor. In those days, it was all I had.”

61over

“This is a cover of ‘6161’ from my previous album. It’s a wheezy, harmonium take on that. The original is hectic, this is contemplative.

“I used an old answerphone message from a house I lived in. For some reason it taped an entire conversation. I thought, ‘That sounds pleasant. Let’s stick it on the record’.

“I had time to do things like that. Once your bills were paid, you could treat yourself to a week off a month to make music. I mean, free time is so precious these days. You have to magic it out of thin air. But, back then, there were whole long yawning summers of opportunity. And everyone’s out playing in the sun, and you’re inside, chopping up 20 seconds of library music [laughs].”

Lights

“The vocals sound chopped on beat. But, I built the instrumental track, which is essentially just a synth and a drum sound. Then time-stretched it, twice as long. Then sang along with a slowed down version. Then time-stretched it back.

“So, the vocal sounds like I’m singing really fast. And, because of the quality of the sounds, and the time-stretching algorithm in the Akai sampler, it sounds like there’s kind of aliasing and glitching. Quite sympathetic with where the beats fell.

“And then there’s a reference to time-stretching in the lyrics. I just thought it’d be quite fun. It’s very autobiographical. That lyrics also list off some of the jobs I used to have.”

Hilted

“The intro is done on a Game Boy, actually. There’s a piece of software called Little Sound Dj, which comes on a cartridge. And you can use it on the original bulky grey Game Boys.

“So, I just laid out that pattern... I think I was on a train journey, one day. And then it sort of bursts into this, kind of, XTC-sounding, I suppose, indie pop?

“I wanted to do something, again, distancing myself from the traditional, anonymous, bloke-on-stage-with-a-laptop, electronic, kind of dude.

“And then the cello comes in. And there’s actually a banjo, as well. The only time I’ve played the banjo on record. It just kind of lifts it a bit.”

Acorns

“When I listen to some types of dubstep records, the rhythm is very similar to the rhythm in this. Maybe someone on that scene heard this?

“Then it’s me and my sister, singing. And there’s trumpet harmonies, and a field recording of a friend of mine who’s about to embark on a vocal performance.

“So, it’s just her introduction, which is in the background of the intro to the song. And then it goes into our singing. For no reason at all.

“I just like the idea of making people feel ‘happily unsettled’, I guess. I’ve never said that out loud.”

Gondry

“That’s a reference to director, Michel Gondry. It’s essentially me requesting he directs a video one day [laughs]. He ended up using it on his compilation DVD, as closing credit music. So, that was quite funny.

“The music has a loose, disco-y sound. And the BPM slowly creeps up as it’s playing. As if it’s a real, old, live, disco record. Like, a real drummer playing for 10 minutes.

“All the keys are played live. And it’s a real Fender Rhodes, which I no longer have, but you can see it on the back of the album sleeve. And there’s no sequencing on it, apart from the drums, just to give it an organic feel.

“Yeah, it’s just my effort to do a proper-sounding disco track.”

Labial

“I think I was running out of six-letter track titles [laughs]. Anyway, in the first two thirds of this, all the sounds, including percussion, are from the Nord Lead 3 sound palette.

“There’s a Japanese musician called Kimitaka Matsumae, who’s a huge influence on me. He made music with only a Nord Lead 3. So I wanted to showcase this synth. It’s about setting myself these limitations.

“You could do so much on it. And, because I’d get hyper detailed with the sequencing, I’d layer each track, one-by-one into the hard disk recorder, and do live turns of the dials. There were so many, that one was bound to affect the psycho acoustic property of the sound.”

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues