Massive Attack on their production process, key collaborators and secret studio weapons

Stew Jackson and Grant Marshall talk guitars

Introduction

In the backwoods of Bath, the creative cogs of Massive Attack are turning as Stew Jackson and Grant Marshall, aka Daddy G, discuss the inspiration and execution of the band’s world-class music.

Stew Jackson, while sharing stages with the likes of Sugar Man superstar Rodriguez, is as much at home on the road as a guitar-toting hired gun as he is in the studio, having produced and toured with a range of artists from The Black Crowes’ Marc Ford to Bristolian country-soul virtuosos Phantom Limb.

For nearly 30 years, Massive Attack have instinctively fused together myriad sounds

For the best part of a decade, he has also collaborated alongside Massive Attack founding member Grant Marshall with a divergent line-up of vocalists such as Nick Cave, Patti Smith, Mazzy Star’s Hope Sandoval, Blur’s Damon Albarn, Rival Sons’ Jay Buchanan, reggae old-schooler Horace Andy, and Mercury Music Prize-nominated artist Ghostpoet.

The band’s latest release, The Spoils (featuring Hope Sandoval)/Come Near Me (featuring Ghostpoet), is a single from the Jackson-Marshall wing of Massive Attack and the most recent addition to a super-eclectic musical legacy that stretches back to the 1980s.

For nearly 30 years, Massive Attack have instinctively fused together myriad sounds from hip-hop, reggae, funk, soul and punk to produce electronic masterpieces of multi -form music, with guitars often featuring heavily in the mix.

With more music on the horizon and a recording session in full swing, the guys invite us down the garden path to an unlikely studio location - a humble shed, favoured by both Stew Jackson and Grant Marshall as their creative base for the last few years. Fittingly, it’s the kind of unassuming, common-or-garden - albeit offbeat - place that evokes a sense of grass-roots fantasia and everyday nostalgia…

Shed heads

We bet you didn’t think, 20 years ago, that you’d be sat in a shed at the bottom of a garden?

Stew Jackson & Grant Marshall: [laugh]

It’s all about experimenting. The thing is, just get the idea down! In a rough form

Stew: “Ahh… The lifestyles of the rich and glamorous, eh!”

Grant: “It’s all about the basics and the ideas; it’s not about plush studios and stuff like that. It’s about brilliant ideas, being innovative and having a great imagination.”

How many tracks do you guys have?

Grant: “We’ve got a lot of tracks. How many we’ve started and how many we’ve finished is completely and totally different!”

Stew: “On this hard drive, there are 131 tracks. On my other one, there are about another 160. Some of them are just guitar parts. Some of them are just grooves. Some of them are whole tunes that we now hate.”

Grant: “There’s a lot of legs left in them, y’know. It’s all about experimenting. The thing is, just get the idea down! In a rough form. There’s a lot of things that we’ve gone through now that we laid down about a year ago that we’ve dragged out of the cupboard and dusted down.”

Stew: “Sometimes, we’ll be farming ideas out to singers - you can hear all the possibilities where it can go in your head, but you have to resist because you don’t know what that singer’s gonna do.”

Grant: “If you want to work with someone, you want to work with them because of their thing. You think, ‘Maybe a little bit of their thing would mix really nice with our thing.’”

From singer-songwriter to orchestra

How do you get an idea to them?

Stew: “Sometimes it’s just grooves and chords. Really basic chord structures are generally the thing. We’ve been known to re-record ideas that we know would suit the singer better.”

A lot of what we’re trying to do is songs as well as cinematic pieces of music. Just good songs

Grant: “Hope [Sandoval], for instance. We’ll do an acoustic version of it [the track]. Stew will give it to Hope in a form that she would probably be making a song in - an acoustic guitar and chords.”

Stew: “A lot of what we’re trying to do is songs as well as cinematic pieces of music. Just good songs. So you know this tune [plays Massive Attack single The Spoils], this was the original idea… [plays acoustic guitar/vocal demo version]. This is what she sent back - same vocal.”

Grant: “We went to Spain to do the orchestra on this - a 50-piece orchestra.”

Stew: “Dan Jones did the arrangement. He conducted it as well.”

The people that you give ideas to - are you fans of their music?

Grant: “Yeah! The good thing about working with Stew is that he’s brought a lot of people to my attention. Stew really likes Nick Cave, so we thought, ‘Why don’t we do a track with him?’ You can go from Horace Andy, a Jamaican singer, to Nick Cave. It’s a brilliant thing that we can do that, as Massive Attack.”

Jump in the pool

So it’s a creative pool in a way, like DJ’ing, for example?

Stew & Grant: “It is that!”

It was easy to go in and make a collage of music from bits of music that we love, because growing up on hip-hop, it was all about that

Grant: “It is that ethos that we had when we started Massive Attack; it was all about the different elements that D [3D/Robert Del Naja] brought, which was the punky thing and the reggae thing. Mushroom [Andy Vowles] was a complete hip-hop head. There’s always been a broad base that we’ve been able to draw from.”

Stew: “As a collaborator, from my perspective and from listening to your records before I started working with you, it’s like a collective kind of thing.”

Grant: “Yeah, it’s always been that. It was easy to go in and make a collage of music from bits of music that we loved. It comes totally naturally to us, because growing up on hip-hop, it was all about that.”

When did hip-hop arrive in Bristol?

Grant: “That was around ’82. We saw Kurtis Blow - that was when we sort of dissected the whole thing about hip-hop. It was amazing that you could create your own soundtracks from two records. The ‘Do It Yourself’ thing was what was so good about it. It was all rebellious music, wasn’t it, really, punk and hip-hop? And hip-hop did have that ‘Do It Yourself’ ethic. And the same thing with punk, really.”

Punk practice

Were you into punk?

Grant: “Yeah! Totally into punk - loved it! I used to go to all the punk gigs. We formed [a punk band] once, to play up on Purdown [in Bristol]. My friend used to work at a mental institute there and every Christmas they’d have a band. We’re talking about 1978.

“We formed this band, The Nutjobs. I was the singer and we got a couple of other guys in and we did this gig. We got thrown off halfway through. These guys were going, ‘Get off the stage! You guys are fuckin’ MENTAL!’ In a mental institute, mind…”

It’s good to be involved with someone else who can bring something else to the table

Stew: “It’s funny, the punk thing. Grant and I talk about it a lot. The rastas and the punks back in the day had a lot in common. Quite fascinating how things, incredibly different in an aesthetic way, are actually coming from exactly the same place.”

Grant: “It’s good to be involved with someone else who can bring something else to the table. I couldn’t work on my own, technically. But working with someone like Stew is perfect. It’s really hard to find this kind of relationship. Ultimately, it’s all about taste.”

Stew: “Taste is everything. And that’s all subjective. How you put a record together is subjective. The technical aspects of putting music together can be helpful, but the only reason to know the rules is so you can break ’em.

“We use weird things for bass a lot of the time. A lot of the sounds are made out of guitar that aren’t any more - like the original guitar signal is taken out completely - using it to trigger tuned reverbs, or whatever.”

What about drums?

Stew: “There’s the tune we did with Nick Cave that’s got samples from the Chamberlin, which was a precursor to the Mellotron. It had a thing on it called a Rhythmate that had a load of drum samples and I cut up a bunch of samples from that.

“Gyroscope is the working title for the Nick Cave track and it’s got an old Chamberlin Rhythmate thing on it, which is odd and is incredibly noisy, but it sounds cool. We do a lot of banging shit that shouldn’t work. There’s a cake tin behind you that makes a pretty good snare drum when you put paper on it.”

Key gear

And is that a Martin 000-28?

Stew: “That’s a 000-28, yeah, with a wacky scratchplate on it. ’98, I think. It used to belong to a flamenco guitarist. It records well.

On the Ghostpoet track there’s a sound that’s the Martin through an amp

“I had a D-28 as well - I did like it, but it’s too boomy for a lot of the stuff that I do, whereas with [the 000-28] you can keep them exactly as they are and there’s loads of bottom-end in it. It just has a ceiling of how loud it’ll get. It doesn’t feel squished, but it will only get so loud.

“On the Ghostpoet track there’s a sound that’s the Martin through an amp. That’s using the BMF Effects El Jefe [overdrive pedal], which I love, and the Fishman Rare Earth pickup, just plugged into my Fender Blues Junior III - one of those limited-edition Texas Reds.

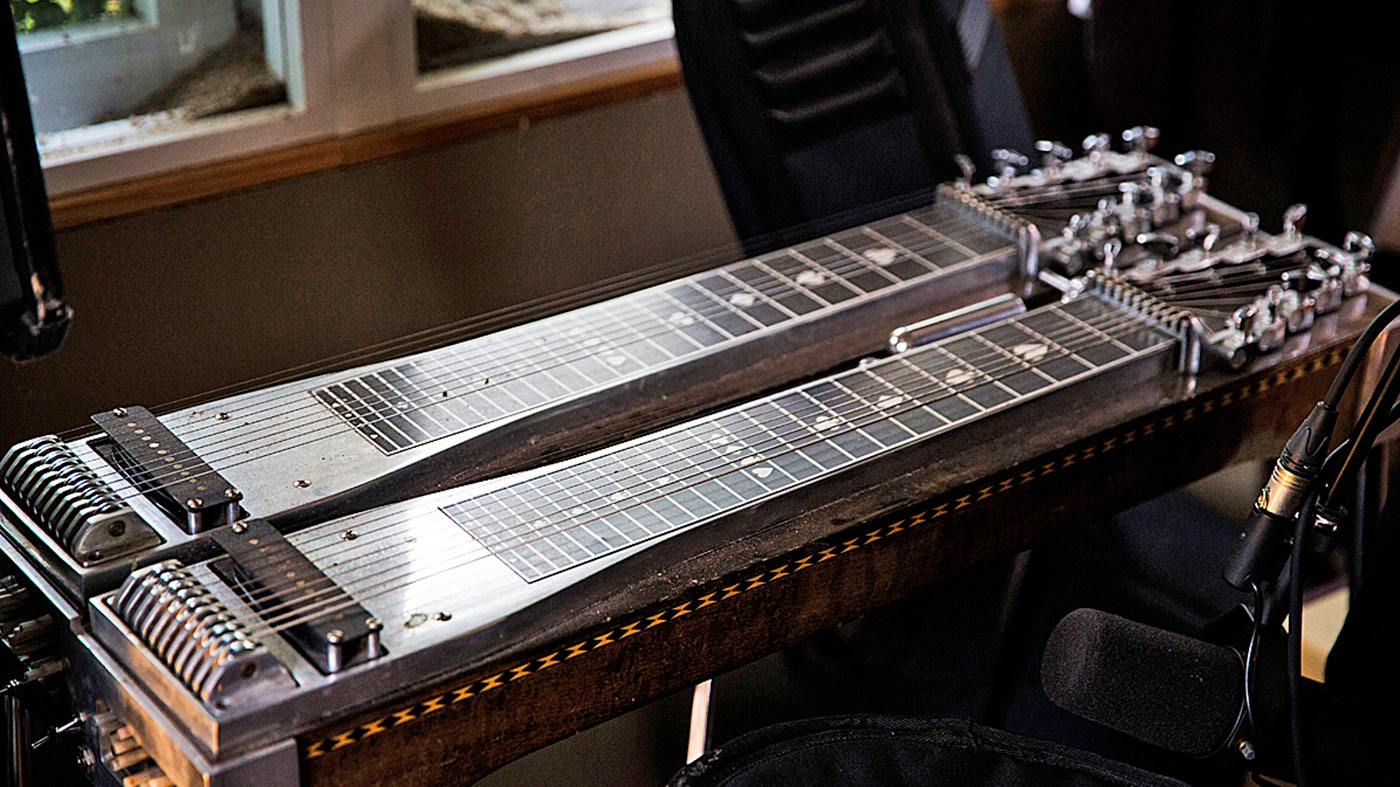

“I have a couple of Blues Juniors, a Fishman Loudbox, an Orange Tiny Terror, a Sho-Bud Super Pro pedal steel, an Ozark resonator, a banjo, a ’73 Fender Precision Bass, a Kala U-Bass…

“Pedal-wise, I use the Electro-Harmonix Freeze quite a lot. I use an Analog Man Sun Face germanium fuzz; this one’s the NKT-275 one. I also have a Red Witch Pentavocal trem, which is rad, and an MXR Carbon Copy, which I use a lot. When I go out live I use the BMF Effects Fat Bastard, El Jefe and the Ge Spot.”

Gibson guy

And you’re more of a Gibson player?

Stew: “Yeah, but that’s just what came my way, rather than anything else. One of the first guitars I had was a Westone Thunder IIA - that was the only [left-handed] guitar around I could play. It was a Gibson scale, so I just got used to it, and when I played Fenders, it didn’t feel right. It does now, but I still don’t play any.

I told him I wanted my SG to sound a bit like a Tele, so I think it’s a Twangmaster in the bridge that’s really underwound

“This is the only thing I’ve got that has a longer scale [Stew shows us a custom guitar that his brother and Bristol luthier Martin Bailey built]. It’s an Alnico IV in the bridge and a super-microphonic lipstick tube pickup.

“It’s quite cool to record with, but it can be a bit squeaky. I toured this guitar once with Rodriguez. I just used it on a couple of tunes for that really stupid, very-little-sustain, open, bassy tone. But I wouldn’t have taken it out with Marc [Ford].”

Did you take your SG out with Marc Ford?

Stew: “Yeah, I took that out. In the States people were like, ‘What’s goin’ on?! Are they wide range pickups?’ They were Lindy Fralin pickups.

“I told him I wanted my SG to sound a bit like a Tele, so I think it’s a Twangmaster in the bridge that’s really underwound - I think it’s less than 8,000… And it’s a P-92 in the neck. That’s a cool sounding guitar - it sounds amazing.”

Going live

How are guitars transferred to a live context from Massive Attack records?

Grant: “D works with [guitarist] Angelo Bruschini, so if he’s doing a guitar part he’ll get Angelo in to do it. So when it comes to rehearsing it’s already a known quantity.

We work with a brilliant team of musicians. ‘The A-Team’, we call them. They’ve reinterpreted Blue Lines, Mezzanine, Protection, Heligoland…

“With us, Angelo will just reinterpret what Stew does. We work with a brilliant team of musicians. ‘The A-Team’, we call them. They’ve reinterpreted Blue Lines, Mezzanine, Protection, Heligoland…”

Stew: “With a lot of the stuff that Grant and I work on, the guitar’s not used in a typical way. We fuck with stuff immensely: massive amounts of making instruments not sound like instruments any more; making drums sound completely synthetic when it’s actually a drummer in a room.

“We do a lot of stuff like that, but we tend not to use presets or stock anything. It’s also a comment on making something, as Grant says, ‘future-proof’. All you could say is, ‘That song was probably put together some time after 1981, rather than after Chuck Berry.’”

Rod Brakes is a music journalist with an expertise in guitars. Having spent many years at the coalface as a guitar dealer and tech, Rod's more recent work as a writer covering artists, industry pros and gear includes contributions for leading publications and websites such as Guitarist, Total Guitar, Guitar World, Guitar Player and MusicRadar in addition to specialist music books, blogs and social media. He is also a lifelong musician.