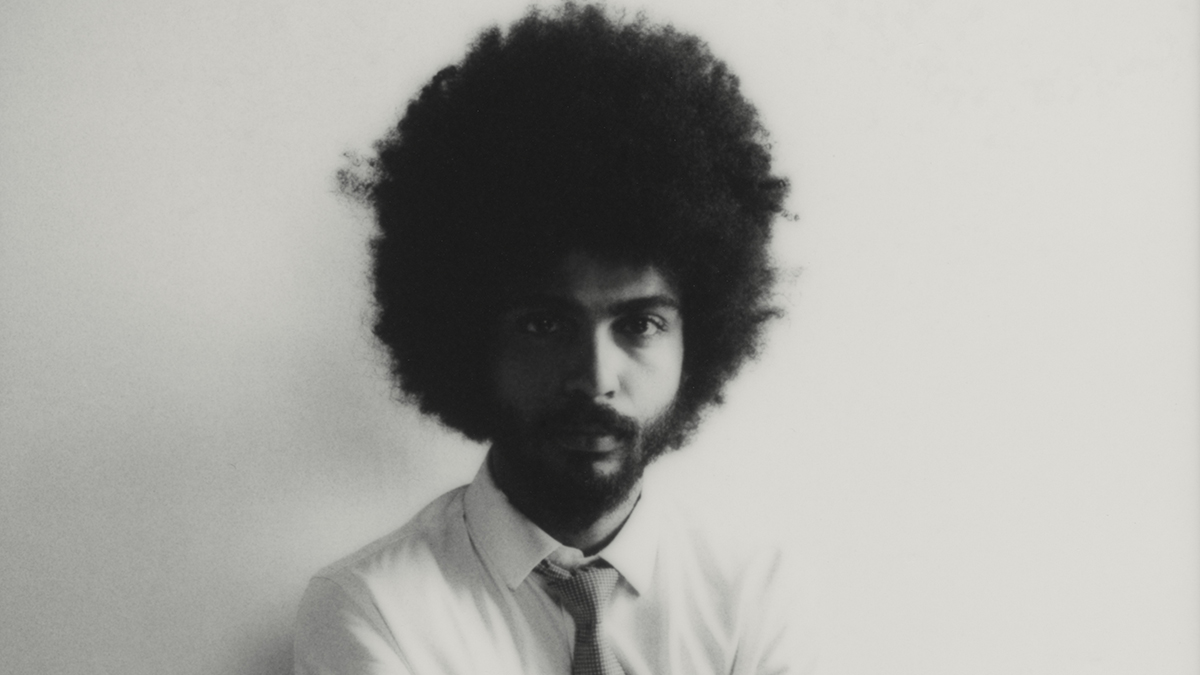

Martina Topley-Bird: "You need to keep adding fresh ideas, you have to challenge yourself. I was hyper-aware that I didn't want these to sound like Massive Attack songs"

Martina Topley-Bird's worked with Tricky, Massive Attack and The Prodigy over a three-decade career, but her fifth album, Forever I Wait, sees her embracing a newfound confidence

“I remember being, like, 13 or 14 and really struggling to work out who I was,” explains a thoughtful Martina Topley-Bird. “My mum was Afro-American and my dad was white. I was keenly aware that most of the black people I knew were either African or West Indian so, culturally, I felt like my family didn’t fit in. I was busy looking for my tribe, but it was obvious that I didn’t come from the same mould as all my peers.

“Looking back, I think that was the point at which music really started to matter to me. My parents loved music and it was always playing around the house – everything from opera to 80s R&B like DeBarge – but music suddenly seemed even more important. It gave me an emotional identity.”

Most of us first heard Martina Topley-Bird on Tricky’s 1995 debut album, Maxinquaye, her seductive yet lonely voice flitting across the cranky, disjointed musical backdrop like some sweet bird of truth.

The success of the album thrust Topley-Bird – then barely out of her teens – into a harsh spotlight that seemed to spend as much time focusing on her personal life as it did the music. It’s left lasting scars and, these days, Topley-Bird doesn’t particularly like talking about the work she did on Tricky’s first three albums.

“The problem with being involved in a project like that is that you are always compared with your history. I’ve done a few interviews for my new album [the recently released Forever I Wait] and all we ended up talking about was the 90s. Yes, I understand that some people are very attached to that era and its music, but it was a fuck of a long time ago.

At one point, I was talking about making four separate albums, each with its own theme

“Somebody described making music as a bit like studying yoga; once you start on that journey, you have to keep going. But to keep going, you need to keep things interesting. You need to keep adding fresh ideas. You have to challenge yourself or you end up becoming stuck in one moment. You stop growing.

“Constantly referencing the past isn’t useful. I don’t want to talk about what I ‘did’, I want to talk about what I’m ‘doing’. A lot has changed in 26 years. I’ve made a lot of music.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

She’s got a point. Forever I Wait is actually Topley-Bird’s fifth solo album – if you count the US version of her 2003 debut, Quixotic – and she’s notched up an impressive and extensive list of collaborations and guest appearances.

Amongst others, you’ll find Gorillaz, Common, Diplo, David Holmes, The Prodigy (vocals for the title track of 2015’s The Day Is My Enemy), Primus (on the leftfield funk-rock extremists’ 1999 album, Antipop) and, arguably her most frequent musical partners, Massive Attack.

Topley-Bird was, of course, part of the same Bristol/West Country crew that morphed into the early versions of Massive Attack, but she’s also provided both studio and live vocals for the band over the years and lists Massive Attack’s Robert “3D” Del Naja as a co-producer on Forever I Wait.

Topley-Bird is something of a restless soul, drifting from London to West Sussex, then New York, Cambridge, Bristol, back to London, Baltimore, back to London and now resident in Spain, which is where we caught up with her at the tail end of 2021.

It sounds like the new album was a long time coming. Apparently, you started work on it in 2015.

“It came together at different stages in different places. Some bits were written and recorded in Baltimore, but nothing much happened with it until I was back in London in 2017. My partner got so fed up with me talking about it instead of getting on with it that we started writing lyrics together in a pastry shop.

“One of the problems I’ve always had when it comes to music is that I’m not always sure about what I want. Most of the time, I’ve got a bunch of lovely stuff sitting on the computer, but it never goes anywhere. I’m pretty sure that I’ve got ADD, so I start flying around with all these different ideas. At one point, I was talking about making four separate albums, each with its own theme.

I was hyper-aware that I didn’t want these to sound like Massive Attack songs

“The other problem I’ve got is that I’m not very good at being a boss. Not good at telling myself what to do. Or anyone else. Consequently, I’ve often found myself in the studio working with other people and ending up with music that I’m not really happy with. We head down a particular road for a few months and then I realise that I don’t like what we’ve created. Well, it’s not so much that I don’t like it. It just doesn’t feel right. I’m sure it’s really annoying for anybody who’s worked with me.

“You know how music works, though… you just need that one idea or one lyric to really get things moving. You get a sense of something and that gives you the courage to say, ‘C’mon, just make your fucking record!’.”

There are quite a few collaborators on the album. Alongside 3D, there’s (Deep Dish cohort) Richard Morel, (occasional Depeche Mode programmer) Chris Berg, (Californian ambient experimenter) Tiadiad and (Baltimore-based multi-instrumentalist) Benny Boeldt.

“Once I’ve got an idea of where the songs are going, then I can start thinking about who I want to work with. I sent them to 3D and he started fleshing out the music side of things, but I was really hyper-aware that I didn’t want these to sound like Massive Attack songs. There was nothing straightforward with this album. Things were constantly moving all over the place.

“The person who ended up becoming my wingman when it came to finishing the album and helping me nail things sonically was Benjamin Boeldt. I knew him from Baltimore, plus he’s a friend of a friend, and he really seemed to know what I was after. He was great at following my instructions but there was nothing mechanical about what he did. He always added his own levels of skill and experimentation… that just happened to be exactly what I was looking for.”

Is there a place you call your studio?

“This is it, really [pointing to the room behind her]. I’ve got Logic running on my laptop, with a Nord Lead keyboard. I have tried Ableton, too. I was given an MPC a while back, but I never really got that far with it. Oh, I’ve got some Loop Station pedals, too. I really enjoyed playing live with them because they seem to have their own independent spirit.

“I do like putting down ideas on my laptop, but I’m not someone who thrives inside that big studio experience. There have been too many times when I’ve been sat there thinking, ‘This isn’t what I had in my head’. What I do enjoy is working with certain people and getting to that moment when you know the chemistry is there and you feel comfortable talking about the song. And there are other times, of course, when you just clam up and do everything by rote. That’s music with no soul.”

We know you as a vocalist, but didn’t you also study piano and violin back when you were a kid?

“Yeah, I studied them both from six or seven years old, but I was also in the school choir. I went to boarding school at ten and the choir teacher there was quite strict… in a nice way. She took choir practice very seriously, which was exactly what I needed. She was really into self-discipline and digging right down into the detail of a piece of music. That suited my obsessive nature. She made us do some really complicated pieces and we performed at the Purcell Rooms in London.”

Presumably, your vocal delivery was a bit different to what we hear on your albums. Or did All Things Bright And Beautiful turn into a piece of Bristol/trip hop-style melancholia?

“That’s hilarious! I suppose my voice was quite forceful compared to what I do with it now.”

We know you don’t like dwelling on the past, but that first time you went into a professional studio, did you have any idea what a Martina Topley-Bird vocal would sound like? Had you found a voice?

“The way I first ended up in a professional studio was almost by accident. I loved music and I found solace in music, but I don’t think… let’s just say the trajectory was very different to how I imagined it. I was all set to do A Levels and then go on to university. I wanted to be an oceanographer. But life happens in strange ways sometimes and this opportunity to get involved with music and record labels fell into my lap.

We’re in this strange place where there’s tons of amazing music being made, but very little chance that people will hear it

“Had I found a voice? Not consciously. God, it’s so hard to think about this because it was so long ago. That first record [Maxinquaye] sounded new and different, so I wanted my voice to sound new and different. It wasn’t cliché music. I wanted my vocals to help connect this music with other people. To connect with different feelings. It needed energy, but it also needed to express a lot of different emotions. Rejection, pain, love, obsession, vulnerability. It was post-trauma music and it really needed a post-trauma vocal.”

The success of that album seemed to come with built-in drawbacks. You didn’t like being ‘famous’.

“The way I try to look at things is whether they add anything constructive to your life. At 16, you think that being famous will be wonderful and it’ll give you the chance to talk about issues that concern you. But I definitely wasn’t cut out for that level of fame or whatever you want to call it. I found it very distracting and, frankly, I would have preferred to direct my energy elsewhere.”

But being a ‘name’ also puts you in a position where people are interested

in your music. Your debut album got a lot of attention.

“Absolutely. I completely accept that. But like I said earlier, being known for a particular project means that everything you do will be compared to that particular project.

Let’s take this and this and this, put it all together and see what happens. That’s me… that’s how I make my music

“What am I trying to say here? There’s a certain amount of infantilisation that happens in the music industry. When you start making money, there’s a tendency for people to start treating you like a child. You’re encouraged to not worry about whether the bills are being paid. You’re encouraged to be useless when it comes to all the common-sense everyday stuff. I found that quite frightening.

“If I compare the recording of this new album with the recording of my first solo album, it’s like two different worlds. I felt like I was in control this time around. There are still millions of things that can go wrong, but I was making the decisions and it felt like it was my record.”

Has that got a lot to do with technology and the fact that you no longer need to rely on record companies and big studios?

“Yes, but the problem you have now is getting people to actually listen to the music you’re making. Even with all the problems I experienced on that first album, the one thing I didn’t worry about was whether it was going to be heard. There was all this machinery in place that made sure your music was out there. Now, we’re in this strange place where there’s tons of amazing music being made, but very little chance that people will hear it. And even if they do hear it, there’s very little chance that you’ll make any money from it.”

Do you think that being in Bristol at that particular time had any influence on you becoming a professional musician? If you’d spent the 90s in Manchester or Birmingham, would we be talking about your new album or would you be on a boat in the Pacific, tracking a pod of whales?

Massive Attack on their production process, key collaborators and secret studio weapons

“That’s an interesting question and one that my partner asked me just recently. I’d like to think that, no matter where I was, I would have found my way into a studio and I would be making music. But there are other times when I watch the news and see a report about a bunch of scientists who are studying pink dolphins in the Amazon and I think, ‘Damn it, you stole my life!’.

“Did Bristol make a difference? I don’t know. I can’t answer that because that was how my life worked out. I was there and, yes, it had a lot of energy. Physically, I like Bristol. I like the topography. I like the fact that parts of it are high up and you get the feeling that you’re looking down on the city, especially at night.

"I like the fact that it’s close to the water. Some parts are very built up and some parts feel like you’re getting back to nature. It’s got some very old parts and some very modern bits. I even like the weather in Bristol.”

What about the music scene?

“We all know about the history of Bristol – it’s a city that’s built on slavery. And yet… it’s also a city that has thrown together a lot of different people and different cultures.

“When I was living there, I remember seeing street names like Black Boy Hill and being very angry about it, but also being blown away by all the great music I could hear in the various neighbourhoods. When I was growing up there, my elder sister was listening to ska and 2-Tone. There was reggae and hip-hop, funk, R&B, African stuff happening, indie music if that was your thing.

“When I was walking around Bristol, I could see all these different people interacting with each other. Interacting with all that music. If anything, I suppose Bristol had a passion for mixing things up. Let’s take this and this and this, put it all together and see what happens. Maybe that’s why I felt so at home in Bristol. That’s me… that’s how I make my music.”

A perfect collaboration

Baltimore-based producer Benny Boeldt helped write, record and mix several tracks on Martina's new album, Forever I Wait.

“I know Martina from the time when she was living in Baltimore and we actually started working on a few things before she went back to London. Life kinda got in the way for a while, but the pandemic was the perfect time to get reacquainted.

“Basically, Martina had a bunch of incomplete songs and we tried to get them into some kind of shape. I was in Baltimore and she was in Spain, but Zoom and Audiomovers took care of that. We could listen to things back and forth, try different mixes, add a few effects.

"Martina really liked the sound of the Eventide H3000 – I’ve got the hardware version – and we ended up using that a lot. You can hear it all over the second track on the album, Wanted. I also added a bit of percussion from my TR-606.

“I do use plugins, but a lot of my main gear is analogue. I’ve got a modular setup, a Juno, a Moog Rogue and the desk is a beautiful Phillips MD12. It’s from the late-60s, 12 channels, no panning and heavy as fuck. This thing weighs about 400 pounds!

“My platform is Reason, so I couldn’t just jump straight into Martina’s Logic sessions. We had to import everything into my setup. Reason is fantastic for audio editing. A lot of my friends who are in bands say, ‘I don’t get Reason,’ but all I can say is, as an electronic musician, I don’t get Logic. For me, Reason is the most intuitive platform out there.”

Boeldt is currently recording as Mezey, and his latest EP can be found on Bandcamp.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

![Gretsch Limited Edition Paisley Penguin [left] and Honey Dipper Resonator: the Penguin dresses the famous singlecut in gold sparkle with a Paisley Pattern graphic, while the 99 per cent aluminium Honey Dipper makes a welcome return to the lineup.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/BgZycMYFMAgTErT4DdsgbG.jpg)