Mark Richardson: “Always insist on being in the conversation. That’s a tip for any drummer”

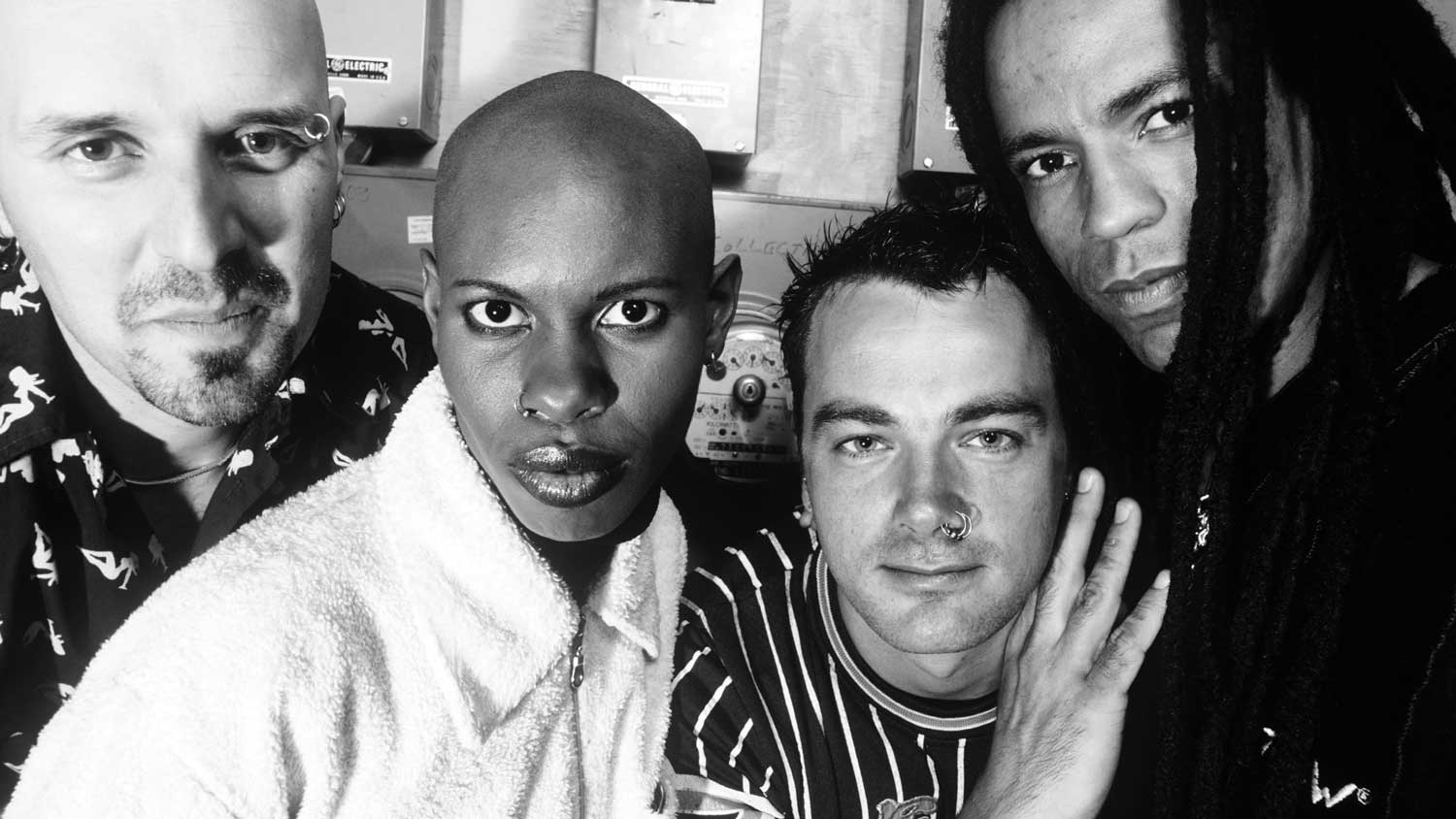

As Skunk Anansie reaches their 25th anniversary, we sit down with Mark Richardson for an open and candid look at one of the most varied and interesting drum careers in UK rock

As one of the best known drummers in '90s British pop, Mark Richardson has a lot of tales to tell, and with Skunk Anansie turning 25, what better time to relive them…

Let’s go back to Little Angels - you were 21 when Jam was released, what was that like?

“Just this morning I was comparing the inside of 10 Miles High to the inside of the new Skunk record. Those collages never get old, the laminates, broken drum sticks… and spliffs!

“There were some pictures in the 25 Live box set, and there’s loads of me still drinking in there. I haven’t had a drink in 15 years, but I had 10 years of good times before that! It’s weird looking back at that stuff.

“I grew up in Whitby, and I was at college in Scarborough. At the time I wanted to go into the armed forces and become an electrician. That was my fallback, even though I thought, ‘I will be a musician and a drummer in a rock band’ there was also the realistic side to it. That seed was mainly sown by my dad going: ‘You need to have a proper job, son.’

“I was in my own bands – King Louie and Black Ice and all sorts of crap names. Good little bands, but none of them went anywhere. I went to see this band called Mr Thud [Little Angels’ early name] at the Stephen Joseph Theatre In The Round, which is more of a dramatic theatre, really.

“But they also had this little venue at the other end that held about 100-150 people. They played there every week or two and I got to know them a bit, then eventually started helping them out loading their gear. I thought, ‘The life of a technician isn’t too bad, maybe that’s something!’ They went from there to a bigger theatre in town: about 2,500 seater, and they’d fill out the ground floor.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Then to cut the story short, they were building this amazing reputation and got management and were signed to Polydor. They got a new drummer called Michael Lee who we all know and love.

“I always like to tell it this way round: I have Steven Adler’s heroin addiction to thank for my start in the music business. Steven Adler got fired from Guns ’N Roses, then Matt Sorum moved from The Cult to replace him, and Michael Lee moved from Little Angels to The Cult, and I moved into Michael Lee’s seat.

“They rang me when Michael left, because I’d basically made a nuisance of myself! I’d auditioned for them a couple of years before but I was a bit too green at that point. They called and asked if I could do this TV show with them.

“I didn’t realise at the time that they were testing me out, the following day they asked if I could come and replace the drums on these drum machine demos they had recorded.

“So they tested me in the studio, but I think the biggest thing with Little Angels was that we were from the same town, same sense of humour and I could do what they needed me to with the drums. They knew I could play, and they knew they could get on with me. You’ve got to have a laugh and you have to get on.”

Have you ever got to tell Steven Adler that story?

“No, I’d love to meet him though! I hope he’s doing alright. It would have been so good if he was back in on the reunion, I guarantee it would mean more to him than anyone else.”

I made plaster of Paris moulds for false teeth. I did all sorts of jobs just to get money to buy drum sticks!

So you went from being at college to playing in a signed band fairly quickly?

“Yeah, and going from dreaming about it: waking up everyday and thinking, ‘I have to be a drummer in a rock band, otherwise I don’t know what I’m going to do.’ Because I couldn’t sit in an office every day, I couldn’t work in a warehouse every day.

“I worked in a warehouse sat at the end of plastic moulding machines cutting the excess off Hoover crevice tools for eight hours a day. I made plaster of Paris moulds for false teeth. I did all sorts of jobs just to get money to buy drum sticks!

“But I sort of knew I had to do it, I didn’t know how, but I just had this belief that it was going to happen. There was no doubt in my mind, and I don’t know where that came from. It was just there.

“So then when it actually happened it was just incredible. I was this kid who had grown up dreaming of the bright lights, then all of a sudden I was in London living in a rented room in Wood Green going, ‘How the f*ck did I get here?’”

What were those first sessions like?

“Well, it wasn’t my first time in the studio. The studio where I replaced those drum machine parts, I think it was called Samurai, near London Bridge. I definitely felt the red light fever.

“Yeah, it was fairly relaxed, but there was a weight to it where I knew how important it was to get it right. I’ve never been an extremely fancy drummer, I’ve never needed to be.

“I love what I play and what I’ve recorded and in some respects it’s been sort of a blessing having a more simplistic overview of a song. I was just listening to that artist, Fink – just beautiful patterns, really well played. And that’s what I love about drums, when you can listen to a beat and just float away.”

How much of that do you credit to the way you learned to play - self-taught playing along to records?

“I never had any lessons… actually that’s not true, I had about six lessons from a guy called Fred Adamson who used to be Bruce Forsyth’s TV drummer, funnily enough. But that was it. I was never a big one for practising. Give me a drum kit, put on Queen’s Greatest Hits and I’ll play it note-for-note, you know? I was just always a huge fan of playing along to other people’s music.”

And as well as picking up beats and fills, you were probably subconsciously picking up a great appreciation of songcraft…

“Yeah, transitions, and how simple 99 percent of popular music is. The stuff I was listening to was Iron Maiden, Queen, Led Zeppelin, The Police, Blondie, Thin Lizzy, all these brilliant bands. But one thing all of those guys had in common was that there was an obsession with supporting the music and not being flash and showing off.

“Not saying that I wouldn’t love to be able to do that flash stuff, of course I would! But it’s not something that ever really interested me, I put a lot of work into playing simply really well.

“‘How can I play the section before the chorus in order to make that chorus even better than it already is?’ It’s more that thinking that I come from. There are tonnes of brilliant drummers out there doing clinics and all that kind of stuff, doing unthinkable things with all four limbs and I admire it immensely, but it’s never been attractive to me to learn.

“It’s hard to say that without sounding like a) I don’t want to put the work in or b) that I haven’t got the talent. It’s not that, although both of those might be partially true! It’s about a love for simplicity of music.”

Your body of work wouldn’t sound the way it does if you were trying to throw polyrhythms over them…

“And actually, all the songwriters that I’ve played with – I’ll put complicated and interesting things forward, always, because I want to know where the boundary is. Things like ‘Skankheads’, ‘Charlie Big Potato’ will get through, but more often than not it comes back to providing a very simplistic bed on which the song can build from.”

The drums on Jam [Little Angels] sound huge - you got a taste of that sound right at the end of the ‘hair rock’ production trends

“It was incredible. Pete Thomas [Elvis Costello] recorded a bit of it, and I recorded some of it. Because I came in late and it was a big expensive studio, they needed to guarantee that they were going to get it down.

“They were still using two-inch tape and it was being edited and all of that kind of stuff. Pete was amazing, he taught me an incredible amount about being in the studio.

“Everything from choosing the right drums and heads, tuning, cymbal selection, what sound suits the song. He knew how to tune the kit to get that massive explosive sound, he was very generous.

“It was an awesome time, and it was my first big session in a big studio. It was intimidating and daunting, if you look at the inside sleeve you can see the weight on my shoulders.

“I’m first in the frame, looking down having a bit of a break and you can see I’m thinking, ‘Fucking hell, this is tough!’ But I’m surrounded by drums and having a great time too.”

Then it went to Number 1…

“Yeah, my first big record I was involved in and we had a Number 1 hit! That’s kind of the only Number 1 album I’ve been involved in.”

I always find that the jazz players who turn rock are the most interesting. Like Jimmy Chamberlin, Robbie and Charlie Watts to some extent

You did some big tours with the likes of Bon Jovi and Van Halen too…

“Yeah. I’ve played supports with some big bands throughout my career, and one thing I’ve noticed is the bigger they are, the nicer they are. A lot of the time the smaller the band is the more attitude they have. It’s strange, but makes a lot of sense as well.

“There are so many stories. We toured with Bryan Adams, he was like a brother, just so nice – he’s on ‘Too Much Too Young’ and he’s in the video. We toured with Bon Jovi, and got to ride on their private jet. They said, ‘Why don’t you come on the plane with us!’ It was amazing.

“Jon Bon Jovi came into our dressing room at the end of the tour, which was Milton Keynes Bowl, and gave us all one of those yellow waterproof Sony Discman when they first came out.

“He came in with this massive bag, and he’d taken a helicopter into London. £500-worth of presents, must have cost him about eight grand! But it was so nice, just to say thanks for being the support on the tour.

“Bon Jovi and Bryan Adams were amazing, but somehow Van Halen seemed to have this extra gravitas to them. They hadn’t been to Europe before with Sammy Hagar, and we were supporting them. They were lovely, and Michael Anthony really taught me to drink.

“You wouldn’t see it now, but their stage went up with these wings at the side of the stage. Their techs were underneath these risen wings at the side of the stage, and on Michael Anthony’s side one of his flight cases turned into a bar! You lifted the top off and there were all these optics, ‘What do you want, Jack Daniels or Jack Daniels?!’

“We’d go down there to watch the show from there and there was a stripper pole in one corner, and you’d get given half a pint of JD and half a pint of coke. That happened every night for the whole time, it sounds really wrong these days but it was incredible! Nobody died, nobody got hurt, it was just good innocent fun.”

From there you found your way into Skunk Anansie…

“After Little Angels split, Bruce, Jimmy and I started B.L.O.W. We released a live EP and a couple of bits and bobs on our own label. We got put up for an award at the Kerrang! Awards in 1995 for Best New Rock Band.

“The week before the awards – I was living in Nottingham at the time – me and a mate saw the video for ‘I Can Dream’ in a kebab shop! We went and saw them at Rock City and it blew me off my feet.

“I saw them over the other side of the room and went over (a little bit pissed) and said, ‘I saw your gig and I loved it, but your drummer’s a bit shit!’ and I didn’t mean to say it like that, and I apologise every time I tell this story because Louie is such a lovely guy. I just meant that he didn’t have the ‘oomph’. Skin just laughed and invited me to audition. I went along and that was that!”

It all happened quite quickly for Skunk didn’t it?

“Yeah, Robbie France recorded the first album and then they had an appearance at Glastonbury early on the bill. But in between that, ‘Little Baby Swastika’ came out and got played by John Peel.

“They did two gigs at the Splash Club, one for friends and family and one for the industry. By the end of the night they were signed. I joined and then ‘Weak’ came out.”

With the toy drum kit and you playing traditional grip in the video!

“Yeah, which I don’t ever play, that grip, but I had to on that kit. The story behind that is that the label One Little Indian didn’t want to pay to release another single. We went, ‘You have to release the single, it’s the best song and the biggest chance we have of a hit!’

“So the short version is that we were in the US on tour and we said, ‘You have to release this song’. They said, ‘We don’t, and we’re not paying for another video.’ So we said, ‘We’ll pay for the f*cking video, will you release it then?’ And they did.

“So we paid for the video and shot it very quickly and cheaply at an airport in Santa Monica. We shot it in between flights taking off!

“We had the same problem later with ‘Hedonism’! There was no rhyme or reason. We’d saved that song from the first album so we would have a hit on Stoosh then we had a fight on our hands, again. Labels are just weird, and that’s putting it politely!

“Sounds weird, but when you get a song like ‘Hedonism’ – a lot of bands get sick of playing songs like that – but for me that song, and ‘Weak’, it’s a celebration.

“Those songs paid for my flat. When all I dreamed of was being a drummer in a rock band and maybe make enough money to save up for a deposit on a house, along comes a song that pays for it.”

And when fans are paying to see you, they want to hear their favourite songs played enthusiastically...

“Exactly, you have a duty to play those songs and be proud. Not fart around while you’re playing and chat to each other, but to do them justice.

“Those are the songs that the fans are really invested in. The amount of people who come up to us even now and say, ‘Those songs helped me through a really rough time’… it’s really humbling.”

The toms sound big on Hedonism too…

“Yeah, and that’s all Al Jackson! I was listening to Al Green at the time and I was playing a straight groove to ‘Hedonism’. Skin asked if I could do something a bit more interesting so I went, ‘Yes I can, thank you Mr Jackson!’ Mr Jackson, whose fills consist of opening a hi-hat and hitting a single tom!”

A lot of the time these big arenas are so echo-ey and crap sounding that the simpler you play, the better

Skunk has always had a strong sense of groove – an ability to make people’s heads move, that’s partly down to you

“When we had our break and got back together, the first thing we wrote was ‘Tear The Place Up’, which is sort of drum’n’bass, gets you moving. So, yeah, we do like to consider making the audience move when we’re writing!”

You came into Skunk after Robbie France. What was that like?

“I used to watch Robbie’s drum videos. What an amazing drummer – I always find that the jazz players who turn rock are the most interesting. Like Jimmy Chamberlin, Robbie and Charlie Watts to some extent, I guess. It’s just a unique take on the kit.

“But, weirdly, I took to Robbie’s parts a lot easier than some of Jon Lee’s stuff in Feeder. Jon was incredible, there’s some really tricky bass drum parts in there, especially in the earlier stuff.

“On some of the longer songs there are these really cool patterns that make you go, ‘Bloody hell, how did you come up with that?’ Taka is always 16ths on the bass, so that freed Jon up to put the bass drum wherever he wanted.

“When I joined Skunk he just said, ‘Just make it your own, don’t try and play like Robbie.’ So that’s what I did. In all three bands I replaced really great drummers – Michael Lee in Little Angels, Robbie France in Skunk Anansie and Jon Lee in Feeder.

“So I’ve not been in any of them from the start, apart from B.L.O.W. so I was in this position where I had to make the songs my own, but keep the essence the same. That was really fortunate because a lot of artists might have said, ‘Do it exactly the same’ but I’ve been allowed to be myself within these songs.”

Does the first Skunk album feel more like ‘yours’ after so many years?

“It does now that the live album has come out. I was listening to ‘Intellectualise…’ for example. The way I play it is much simpler, but much heavier in some respects than how Robbie used to play.

“His tuning was higher, his sticks were smaller, he was a lot more ghost note-led than I am. And not that I don’t play ghost notes, but they won’t cut through the gates. It just sounds a lot more dense… for want of a better word!

“It becomes more about ‘What are they hearing at the back of the room?’. A lot of the time these big arenas are so echo-ey and crap sounding that the simpler you play, the better.”

Your drumming became heavier, more industrial for Post Orgasmic Chill.

“Yeah, we brought in more electronics, which we’ve always loved to do. We’re going to do some writing in March, and that’ll be the same.

“That’s where we experiment and go way out there with ideas and then bring it back to resemble something that Skunk Anansie would play!”

Was there a learning curve to using electronics and loops?

“It started off being a very different thing. Like the intro for Charlie Big Potato, for example. We never really thought about how we’d integrate that into the song because it was just a separate piece.

“On that record and Stoosh there were electronic segues between the songs. It wasn’t really until the Wonderlustre tour – Skunk Part II – where we started over-laying samples live.

“‘Black Traffic’ has six or eight kick drum samples, and my acoustic one. We came up with this mix of samples with Chris Sheldon. In the studio on ‘I Hope You Get To Meet Your Hero’ I played the song twice: all the way through on the electronic kit then all the way through on the acoustic kit, then we just mixed the two.”

So you’re playing these loops live in the studio?

“Yeah, we tend to always do that. We’d rather make up our own electronic loops with stuff that we find interesting. There’s a track called ‘Spit You Out’ which is really electronic on one hand, but on the other it’s real early-80s punk: that real stiff hi-hat hand, which was a very deliberate feel that I wanted.

“Solid eighths on the hi-hats. We’ve always mixed and matched the electronic stuff, and we used a lot of orchestras too. On the last album we had a song called ‘Love Someone Else’ which is almost entirely electronic.

“I think one of the reasons we can get away with it is because when we’re writing we go way beyond what Skunk Anansie is, then bring it back and find the boundary of what we can and can’t do.”

Two hours is quite a long time when your wrists are f*cked, your back’s f*cked, and you’re just a bit old and f*cked really

You’ve worked with some great producers over the years, what was it like working with GGGarth [Richardson]?

“That was interesting… let’s just say I struggled. I think we’re just very different people. He wanted a very different thing out of me than what I was capable of giving.

“It’s not always smooth sailing with producers and you don’t always get on with everyone. Different producers have different agendas, the best producer I’ve worked with by miles was Andy Wallace who worked closely with us beforehand to get the best out of us as players, for the song and to work with us on them so that when it came to recording we knew exactly what we were doing. The guy’s amazing, he’s just done so much.

“With GGGarth, I’d go into the cutting room and they’d be cutting all the human-ness out of my drum tracks. I’d do my take and then Doug, his engineer, would spend all day cutting it up and removing all the gaps which was essentially my groove.

“My argument is, ‘That’s my personality that you’re cutting out.’ It was tough for me, and it completely shattered the little confidence that I had built up to that point. I was fortunate that the band had my back.

“I knew something was going on, because I’d be sat in the live room after doing a take, and they say, ‘Yeah, just hold on there for a minute’ and you can’t hear them chatting.

“So now I always insist that I have an open mic to the live room, so that I can be involved in the conversation. That’s a little tip for any drummers who are going in to record in a studio for the first time – tell them to keep the mics open so you can hear what’s going on.”

Gil Norton, who you’ve also worked with, is notoriously hard on drummers.

“Gil is a really good person and knows how to get the best out of somebody. He’d communicate with me directly, saying, ‘Can you give me a bit more of this, less of that, bump it up a couple of BPM, try this pattern…’

“I’m really easy going, but the one thing I can’t stand is when people are uncommunicative. I can take criticism, but when you ask someone how to improve something and you get nothing back it just doesn’t work.

“Gil was very cool to work with, I think my favourite tracks I did with him were on a little EP we did in Feeder for Japan called ‘Seven Sisters’. I love the records we did together, especially Comfort In Sound.

“Probably one of my favourite drum sounds: analogue, old-school drum sounds on that old Yamaha. I loved working with Gil, he had done a lot with The Pixies, obviously, and Foo Fighters so he had all these great stories.”

It must have been unimaginably difficult joining Feeder after Jon Lee passed…

“It was horrendous. I remember introducing myself to one of the women in the office. I was so nervous, I said, ‘I’m Mark, I’ve taken over from Jon, I was at his funeral.” It was so wrong, one of those things that you forever regret. It wasn’t that I was saying, ‘Hey! I’m the new guy!’ I was trying to humbly introduce myself, but it was just too soon.

“But, yeah, it was horrible, because Jon and I had a lot of great times together. We met up at a lot of festivals all over the world and we had a very good time. He was a great drummer. That’s the other thing, not only have I replaced drummers in all three bands, but they’ve all died. That was a big part of my sobriety, and giving up messing about.

“Stepping into Jon’s shoes wasn’t exactly pleasant, I don’t think the fans really wanted to accept it. And why would you? You want your Feeder back, with Jon Lee. But it was either accepting someone else or the band doesn’t carry on.

“Grant was very much of the mindset that not only did he want to carry on, but Jon wouldn’t have wanted the band to fold. So they asked me, and Skunk had been over for a year so I said, ‘Yes.’”

Was there a point between Skunk and Feeder where you were unsure about what to do next?

“Yeah, I did little projects, but nothing of note. I’d actually applied to do a tradesman’s course, because session work just wasn’t on my radar at the time. I’d had two amazing, life-changing opportunities by that point and the chances of getting a third seemed pretty slim.

“I thought, ‘I need a trade, I need to be able to make a living if music doesn’t happen.’ I don’t know why I thought that, because I could have done functions, there’s lots of playing stuff I could have done. But then I got the chance to join Feeder. Grant wrote an amazing set of songs on Comfort In Sound. It just made it so easy to play to.”

It must have been cathartic?

“Yeah, I really think it was. Especially for Grant. His way of dealing with everything and anything that happens is to write a song about it. It’s why he’s so prolific, his work ethic around songwriting is just completely incredible. I’ve never met anyone like him – really, he’ll easily write a song a day.

“So that album was very easy to play to, he could hear the whole album finished in his head. So if it wasn’t what I was playing he’d just very gently redirect me and because of that we got a great record.

“We went on to do another two in the same sort of way, really. Some of those songs on the subsequent albums were songs that didn’t make Comfort In Sound. Obviously he’d written a lot of new stuff by then too.”

The album and singles were hugely successful, it seemed like it was being played everywhere

“I think the hardest bit for Taka and Grant, and Matt their manager, was that by that point the band were perfectly poised to make that next jump into the arena circuit, which is of course what happened.

“They had ‘Buck Rogers’ and ‘Just A Day’ between records, they’d made these huge strides up, and then Jon wasn’t around to enjoy it, which was just really sad, and that’s another reason why I ended up starting the Music Support charity.

“There are so many people in the industry, musicians and crew alike that need mental health support. It’s a tough environment, touring. In a way, bands get it easier because they come in and do a soundcheck, have a bit of food, do the gig and then go home.

“Whereas the crew are in there from early doors, first in last out. They’re in there all day with no natural daylight, rigging and putting up PAs. If you’re struggling mentally in any way, then it’s a really tough environment to work in.

“It was something I’d always wanted to do, so we managed to set that up. They work alongside other charities like MIND and Help Musicians UK.”

Tell us about how the charity started

“There were four of us who started it, and we took it in turns to answer the phone. We didn’t have any protocols in place, just, ‘Hello, Music Support, how can I help?’

“The thing that stuck with me most of all was this one guy. He was sat in his car with a pipe from his exhaust into his window and he was about to switch the engine on. He thought he’d give us a shout just to see if there was anything anyone could say to stop him.

“I just spoke to him and said, ‘Will you do me a favour and just not go through with this today?’ He had three kids, married. He was depressed and it turns out his meds were all messed up, he’d been on the same ones with too heavy a dose for too long and they’d stopped working.

“He went back to the doctor, got them adjusted. Then he called back and said, ‘Thank f*ck you were there to pick the phone up, otherwise I’d be dead.’

“Even if we went through all of that shit, just for that one phone call, it was worth it. It’s a huge problem.”

25LiveAt25 spans the whole gamut of Skunk Anansie’s career, what are the highlights of a set for you?

“I really love playing Robbie’s stuff from the first record. I was listening to it this morning. The second track in is ‘Intellectualise…’ and it just makes the hairs on my arms stand on end.

“The only way we could get all the songs in was by using different shows, so it’s mainly one in Italy and one in Poland and then a couple of others. But there are lots that I look forward to: ‘Skankheads’, ‘My Ugly Boy’, ‘Charlie Big Potato’, ‘Intellectualise...’, ‘Selling Jesus’…

“It’s such a fun set of songs to play, and the tours are never that long that it gets too much these days. It’s a long set, it’s two hours. That’s quite a long time when your wrists are f*cked, your back’s f*cked, and you’re just a bit old and f*cked really!”

Headbanging takes its toll, not only on the mush of your brain but on the bones as well! I’ve just had to rethink how I play, and realise that the sound is no different out front whether I’m headbanging or not

You’re known for being an incredibly hard hitter…

“Don’t do it kids, it’s not good for you! I’ve mellowed a bit now, mainly because a few years ago I put a couple of discs out in my neck. I guess from years of bad posture and headbanging.

“My left arm went completely numb, and I couldn’t lift it! My wife plays with us now doing backing vocals and keyboards and percussion and stuff, and she looked over at me like, ‘What the f*ck’s wrong with you?’ I finished the set off with mainly one hand, and the rest of the tour with not much more.

“So, I’ve stepped back a little bit, mainly from the headbanging because I’ve been doing that since I was 10! That shit takes its toll, not only on the mush of your brain but on the bones as well! I’ve just had to rethink how I play, and realise that the sound is no different out front whether I’m headbanging or not.

“And actually what happened was that the band all turned round and said, ‘It sounds really good!’ because I wasn’t performing as much, and therefore much more accurate in my playing. I’ve just reigned it in from going completely mental.”

You were involved in the Tuner Fish Lug Locks...

“I was hitting the snare so hard, it would detune all the time. I spoke to my friend Mike Bigwood who made drums and said, ‘Surely there’s a better tuning lug lock than these plastic things?’

“So we came up with this design over a few prototypes and it ended up being fish-shaped. Mike said, ‘How about we call them tuner fish?’ It was only ever going to be something that we made for me, but then people started asking for them.

“Now there are loads of people out there using them – Abe Laboriel Jr uses them, Thomas Lang loves them.”

You’re playing Tama these days too.

“They’ve been really amazing. They supply me with gear all over the place. I play a matt black Starclassic and it’s just gorgeous. You can tell which one it is on the live album too, it’s really obvious to me because the toms just sound amazing. I felt like I needed to thank Yamaha and Sakae on the record too, because

I had been with them for so long too.

“I’ve played Zildjian my whole career and it’s just the most incredible company to have been with, same for Remo and Vic Firth. They’ve always been there and been really supportive to me. Whenever I need anything, all of these brands just get it. It’s amazing to have that support after 25 years of drumming.”

Stuart has been working for guitar publications since 2008, beginning his career as Reviews Editor for Total Guitar before becoming Editor for six years. During this time, he and the team brought the magazine into the modern age with digital editions, a Youtube channel and the Apple chart-bothering Total Guitar Podcast. Stuart has also served as a freelance writer for Guitar World, Guitarist and MusicRadar reviewing hundreds of products spanning everything from acoustic guitars to valve amps, modelers and plugins. When not spouting his opinions on the best new gear, Stuart has been reminded on many occasions that the 'never meet your heroes' rule is entirely wrong, clocking-up interviews with the likes of Eddie Van Halen, Foo Fighters, Green Day and many, many more.