Manu Katche on TV stardom, A-list sessions and groove-writing tips

Session hero reflects on a career at the top

Solo success

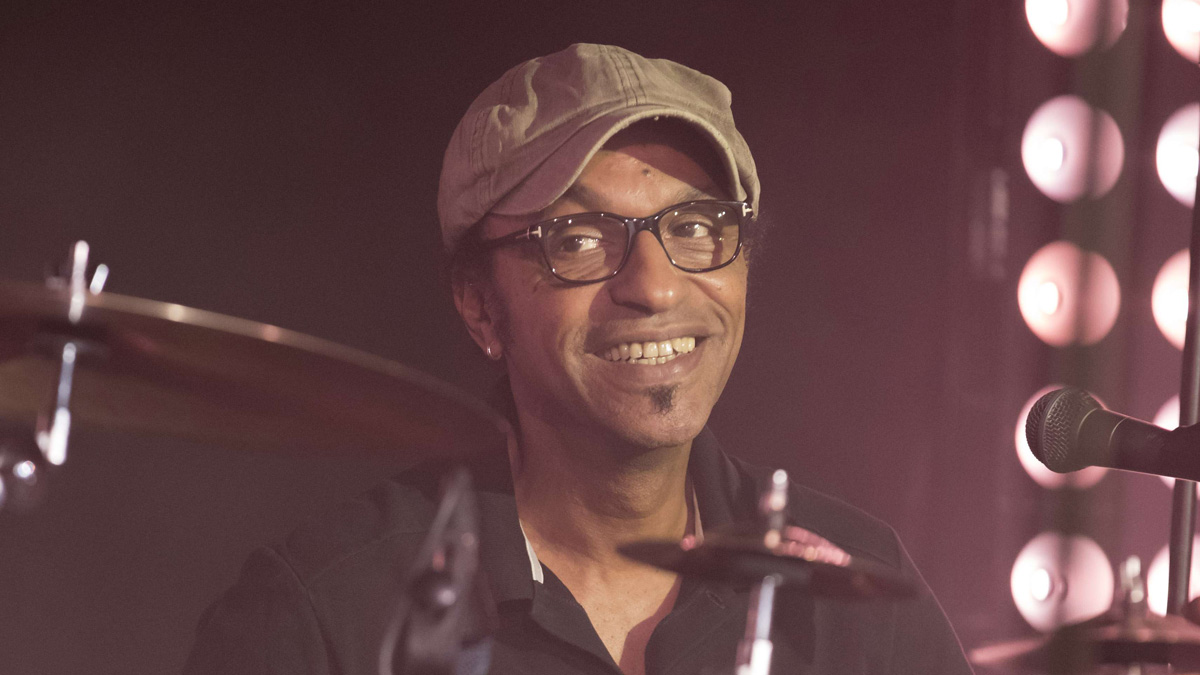

He’s one of the most respected session players in the business, he’s a bandleader, and a TV star in his native France.

He is that rarest of musicians, a chameleon able to adapt to any musical situation yet with a sound and style that are unmistakably his own. He’s Manu Katché.

As a youngster, Katché studied classical piano and percussion. He attended the Conservatoire de Paris but rebelled against the restrictive character of classical music, swapped timpanis for a drum kit and jumped into session work in Paris.

In 1986 his contributions to Peter Gabriel’s So gave Katché’s profile a massive boost internationally and in the decades since he’s worked with an imposing list of music’s biggest names. The drummer’s sublime groove and sparkling rhythmic punctuation have been heard with Sting, Jeff Beck, Joe Satriani, Tears For Fears, Joni Mitchell, Kyle Eastwood, Al di Meola, Jan Garbarek and more.

He’s released six jazz albums under his own name and was introduced to a new audience in France as one of the judges on Nouvelle Star, the French equivalent of X-Factor. He has hosted his own live music TV showcase, One Shot Not, published a book in French about his adventures in music, and turned producer on his latest album Unstatic, which he’s touring to support when we speak to him. “I’m quite busy,” Manu says modestly. “The thing is, it’s not to be busy. There are so many things to do, you want to do them.”

Manu, your band is joined by bassist Ellen Andrea Wang on Unstatic. Does having a bass player change your approach?

“On the previous album, [Manu Katché from 2012] I didn’t want to have a bass player and it was really for myself to try not playing with the basslines all the time. Drums and bass relate to each other so in a way you’re a bit locked to them. We toured for a couple of years as just a quartet with the Hammond B3.

“Of course, he [keys player Jim Watson] played some bass sounds on the pedal board or in his left hand, but it was different. Finally, I said, okay, we’re going to go back to a bass thing and I’m going to write in that direction. As you know I’ve been playing with great, amazing bass players and I thought if I’m using someone it would be nice to have a different attitude.

I write everything on piano then I put everything on Logic, which has all the structures, harmonies and voicing and themes.

“First of all, a female could have a different attitude to a male bass player, and if she is not very well known she won’t have those habits of recreating what you called her for. I thought, I’m going to propose what I wrote for the pieces to her and from that she’s going to go with it. In my mind, it’s hard to explain but I think I got there, it was having a bass player for the balance of the band and of the sound, because I needed that sound back in the band.”

Were there any overdubs in the studio or did you all play together?

“Just all together. We rehearsed a little bit in Germany before getting into the studio and of course when I write, I write everything on piano then I put everything on Logic, which has all the structures, harmonies and voicing and themes. Then I send that to everyone so they have time to rehearse and make it their own in a way because even if I’m writing for them, sometimes I can be wrong.

“Then in the studio we have a couple of days, as it is for jazz recordings, not a lot of time. We cut the tracks pretty quickly, so in two days it was done and then we mixed it. No overdubs. Just the one thing overdubbed is when I talk at the end of the track [Presentation] and present the whole band. That’s an overdub, otherwise everything is done all at the same time, all together.”

Hold that taxi!

It must be very different making an album in a few days versus working with someone like Peter Gabriel who takes months to make a record.

“The album So, that was my first contribution with Peter and we took months to cut the tracks. I remember at the end of the sessions, I was supposed to go back to Paris so I had a taxi booked to take me to Heathrow because we were in Bath, two hours away.

“In the morning we just had to fix a few things in the studio and Peter says, ‘What time is your taxi coming?’ ‘Just after lunch.’ ‘Okay, we’ve got three hours. I’m going to make you listen to something.’ so he made me listen to the track Sledgehammer, which was not Sledgehammer yet, with Chester Thompson playing the drums. I’m a big fan of Chester and I said to him, ‘man, it sounds great,’ and he says to me, ‘yeah but there are some technical problems and it’s not exactly what I was expecting for that track. Can we try it?’

“I said, ‘Of course but remember Peter in a couple of hours I have to go.’ Knowing him it could take months to do one rhythm track and, funnily enough, we did maybe two or three takes maximum and that was it, that was Sledgehammer.

“Sometimes it’s nice to have the comfort and the time to take months to cut tracks and to think about it, and sometimes it’s not. Maybe in a short period of time you’re very concentrated and you just go for the goal instead of fooling around, trying this and trying that. I remember doing some work with Jeff Beck and Tears For Fears, you didn’t have months to cut it. You do three, four, five, six takes but you don’t have months to re-do it.”

I don’t practise drums at home. I play a lot and sometimes I go somewhere else to practise my drums, but what I do at home is I play piano.

When you’re writing music, do you ever start with a rhythm or groove?

“That’s a good question. The answer is no, never. It’s kind of surprising. I don’t practise drums at home. I play a lot and sometimes I go somewhere else to practise my drums, but what I do at home is I play piano.

“I’m a classically trained piano player which means I can’t really improvise, I’m not a jazz player. What comes to my mind first are melodies and harmonies so I sit at the piano and play around, whistle the theme and find the right voicing. I guess maybe somewhere in the back of my mind there’s a groove going on but I wouldn’t say I’ve been inspired by that groove first and then I put the music to it.

“It’s always the opposite. I write on the piano, I put everything in my computer software. If I write a groove on the drums, if I start with a drum loop, a beat, then I’m going to be stuck to it in a way, which means I’m going to add harmonies, the melody, the bassline, the brass section, and then when you get to the studio, I will have to stick really close to what I wrote months ago.

“By not doing this, I have the spontaneity with everyone playing what I wrote, but they’re playing it the way they do, so they’re proposing something new. Then I can have a different approach instead of being stuck to the groove I wrote before. That’s probably why I do that.”

Manu the TV star

You’ve worked with some amazing bassists - Sting, Pino Palladino, Kyle Eastwood. How much does the bassist impact your drumming?

“The thing with Kyle is a bit different because Kyle has a huge knowledge about jazz music and that comes from his dad [Clint Eastwood]. Kyle told me when he was a kid he was going to Montreux Jazz Festival every year with his dad and had to listen to everything, so he’s got tons of information about music and then the way he is, he’s very humble and very quiet.

“When we played together for the Metropolitain album, that was produced with Michael Stevens and the son of Miles Davis, Erin Davis. I remember Kyle coming to me saying, ‘Manu, I like your playing, let’s just go ahead and be free.’ There were some charts for the structure, but that means please do what you do normally.

“Michael Stevens and Erin Davis were in the control room listening to everything and as soon as we cut the track we’d go back to the control room and those guys would say, ‘I like that, it has a good relationship with what Kyle is playing,’ etcetera, so you don’t really ask questions about that. Pino Palladino, Nathan East who did the Joe Satriani album, or Marcus Miller, all those guys are amazing talents like Kyle, but you don’t have any pressure.

“Bass and drums are like a couple, it works or it doesn’t work. Instantly you know and I knew with Kyle and from his personality, he’s not introverted but he’s quiet and quite humble so you know you’re going to be able to propose things in your playing that he’s going to take and then send you other information.”

I was explaining tempo, groove, pulse, rhythm. it made the whole thing pretty awkward at the beginning, they said, ‘Who is that guy? We don’t know him. He’s a drummer, what is that?’

You were a judge on the Nouvelle Star TV show. It’s amazing to see a drummer in that position. Do people know your name and face in France?

“I became well known because it’s on TV, like six million people watch it every Thursday night. I did it for four years so you can imagine doing press and radio. The interesting thing about it is, I’m a drummer so my point of view was very different than just being a judge saying ‘this sounds good, this sounds s**t.’

“I was explaining tempo, groove, pulse, rhythm. it made the whole thing pretty awkward at the beginning, they said, ‘Who is that guy? We don’t know him. He’s a drummer, what is that?’ Then after each programme people knew me. We had a lot of mail from families saying, ‘My daughter wants to play drums now.’ And I was going for it, I was straight ahead, I was not trying to be nice.

“I think people just took me for what I was, serious and passionate. The funny thing is when I started doing some jazz in France with the band in 2004, I met some people who saw me on the TV. Because I was talking about jazz, they were curious to come and check me out and they came and were very surprised.”