LoneLady: "I was given a synth by Brian Eno. It’s a very crisp and weird digital-sounding beast"

Exchanging grey Manchester for a basement studio at London’s Somerset House, Julie Campbell broke out the machines and got started on her third album

Residing in a Manchester tower block for most of her adult life, Julie Campbell’s LoneLady project has been founded on the concrete brutalism of her environment and childhood memories of flickering VHS videos and art school.

Her debut album Nerve Up (2010) featured a crackling miasma of post-punk influences and was followed five years later by the spindly guitars of the funk-driven Hinterland.

For her third album, Campbell sought a new creative ecosystem and found a suitable gloomy residence at a decaying basement studio at London’s Somerset House. In drum machine heaven, the producer created Former Things, her most accessible album to date.

Bristling with heavily programmed electro-pop loops and synth bass, Campbell’s cleverly assimilated vocals eulogise on memories of lost youth with a renewed sense of vigour.

You took up residency at Somerset House, thus relocating from Manchester to London. What precipitated that move?

“Marie McPartlin, the director of Somerset House studios, was looking for a wide range of artists to join their new studios with a remit of bringing people back to London’s city centre. I leapt at the opportunity because I was dying to get out of Manchester and do something different having totally immersed myself and written a personal travelogue about where I came from on my second album Hinterland.

"I was frankly bored of Manchester so it came at a great time for me – a new city gave me totally new stimulus, which was a great starting point from which to write new material.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

We guess Somerset House still contains something of the concrete brutalism in its outwards appearance?

“I always end up in yet another concrete room. All the studios I was shown didn’t work for me because I would have had to share them with people, but we walked though this dilapidated basement room and I thought, hang on, what about this space? It was just perfect.

"The dimensions of the room meant that it wasn’t an obvious studio space because it was very echoey, but I have a history of operating in spaces like that and it was just a way to get me into the building and London.”

I get lost in digital plugins and don’t know where I am. I’d rather move to it just being me, a guitar and a drum machine

Did coming to London affect your mood and therefore the sound of your music?

“I come from an art school background so to be in the heart of London surrounded by loads of galleries was inspiring. I’d not been in a studio since my art degree, so it was the perfect setup.

"It gave me the autonomy and isolation I needed but I only had to step out the door and there were 50 other artists from loads of different disciplines thrumming away and doing their thing, so I had all that to bounce off. I just had a lot of energy while I was in London and that’s fed into the record.”

Did you find yourself sourcing ideas from the other residents there?

“When my door was closed it was just me and the gear in my creative inner world, but once I opened it I was bouncing down the corridor dying to chat to people. It had a more general impact on my creative well-being, but no one had any input into the album in any other way.

"I’m back in Manchester now and talking to you from a much reduced studio space squashed into the corner of my flat. I’ve spent a lot of time in this restricted space and that sort of thing can have a terrible effect on a person’s well-being.

"Sonically, it didn’t matter that I was in London because I wasn’t using the room as a live space, so I could have made the record here, but it wouldn’t have been the same album because I wouldn’t have been the same upbeat, confident person.”

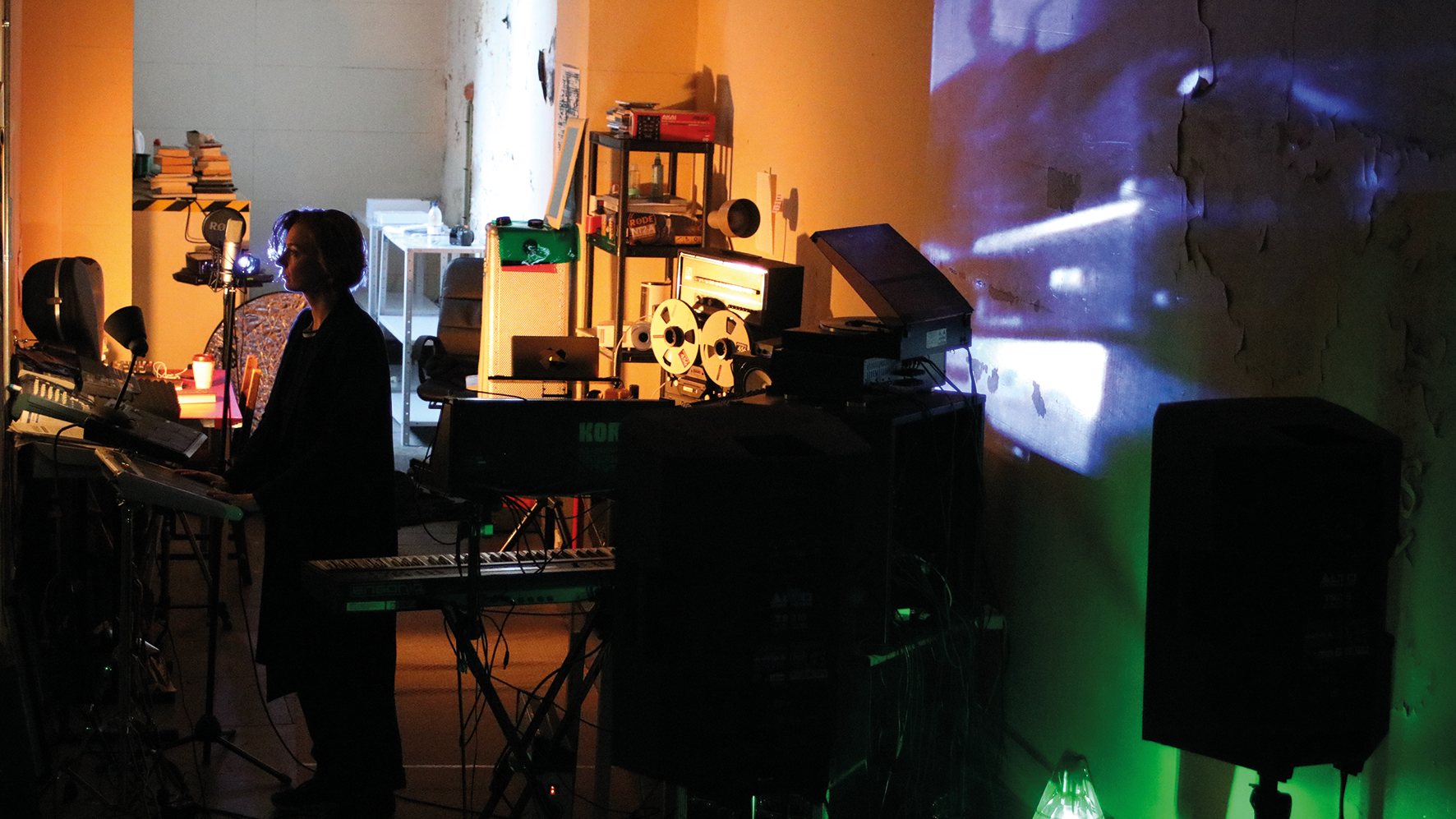

We read that you used projections, notably a selection of Bergman movies and Cabaret Voltaire videos. Was that just for fun or as an act of creative impetus?

“I am fully pretentious and love to make the space I’m in really creative. The room had really big paint-flaking walls and I love projectors so I had three of them going off in there. I projected Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf and Through a Glass Darkly, which is my idea of fun.

"It could be a bright sunny day outside, but I’d get all that going in the morning [laughs] because it stimulated me and put a bit of movement and company into the space.”

I was given a synth by Brian Eno. It’s a very crisp and weird digital-sounding beast

Former Things seems to have more of an electro-funk sound, almost as if you’ve retroactively shifted from the ’70s to the ’80s?

“I never set out to be retro and think there are other artists that are way more retro to the point of being pastiche, which I have no interest in artistically, but I do gravitate to certain sounds and electro reminds me of my childhood.

"I was a little kid in the ’80s and wasn’t aware of cool stuff like Cybotron, but I was aware of films like Beverley Hills Cop that had some of those electro-funk textures. Sonically, the album’s going back to my childhood because I’ve always loved those sounds.”

Do you get the impression that ‘retro’ is perceived as a bit of a dirty word?

“It’s very interesting that the dreaded word ‘retro’ gets applied to electronic music and not guitar-oriented music because the electric guitar’s been around since the ’40s yet a four-piece band is always perceived to be really ‘happening’ and current.

"No one ever describes the guitar as retro, so I do think there’s something weird going on there. Also, there are multiple different types of ’80s music, there’s Cybotron, The Human League or mainstream Stock Aitken Waterman – so what are we talking about when we’re talking about the ’80s?”

We understand Neneh Cherry was an inspiration – the Raw Like Sushi album?

“It’s funny because I had that cassette as a kid but hadn’t listened to it for years. After writing the track (There Is) No Logic I thought, God, this reminds me of Neneh Cherry and when I listened back to Raw Like Sushi I was really blown away by the incredible programming on that."

I’ve owned this £30 Yamaha keyboard since I was about 10 and it’s appeared on all my albums

"Her vocals and delivery were so lively, crunchy and fresh – I think it’s a classic. The new jack swing of Janet Jackson is another – that hard Jam & Lewis sound was incredible. Sometimes there’s a snobbish dismissal of artists like these as ‘pop’, but the sounds and programming were fucking amazing.”

Having a snobbish attitude to pop almost seems to be part of the British psyche. Did creating a more commercialised sound create conflict in you?

“I agree that the album’s a bit more commercial-sounding, but commercial is not a dirty word to me. I worked with Bill Skibbe who mixed Hinterland and that had more of a funk ebb and flow where things were a lot more woozy, loose and groovy, but Former Things was intentionally on the grid, really tight and super-sharp.

"The fidelity of the sounds is brighter and cleaner and my vocal delivery is more direct. I’ve always loved pop music and I’ve always wanted my music to be catchy, so this is my pop album – to the extent that I can get an album to sound like pop.”

You’ve mentioned that you sometimes mourn lost youth. Does some of that derive from the pressures of adulthood and trying to sustain a career in the music industry?

“I reached a point in my life where I thought, God, being a child was quite a long time ago now. I kept thinking about myself as a 13-year-old teenager in Audenshaw. There was an orange light outside my bedroom window and I’d watch VHS videos and dream excitedly about all the things I was going to do and be.

"I’m a sort of romantic, mournful person and those feelings and images are at the centre of the album and I’ve poured all of that into the lyrics.”

The album’s a joyful smorgasbord of different drum machine textures and percussion, which forms a kind of scaffolding

Your vocals have undergone a noticeable change. It sounds like you’re no longer holding back with it?

“[Laughs] I didn’t know I was holding back until I listened back to Hinterland and thought, God, I kind of was – I could hear my shyness. On this record I felt that was stripped away and it was time to tell things as they are.

"The music’s very urgent and so is how I’m feeling about everything. It’s very hard to sustain myself and living in London as a full-time artist I did hit a very rocky patch when I came back to Manchester, in terms of finding a way to finish the record. It was two-thirds done but I struggled to get the last third over the finishing line.

"Lockdown actually reduced my feelings of anxiety because the world got a lot calmer and stiller – so it helped me. It was interesting to see the world forced to function how a solo artist or any freelance person functions, working at home and experiencing a lot of financial instability and uncertainty. It was a weird flip.”

How do you think financial pressure affects artists creatively?

“All the practical apparatus around having a career are a different thing to creating art. For me, the last few years have been like being dragged over broken glass, but I’m really happy to have the album out.

"I’ve had a bit of bunker syndrome, which is a bit intimidating and I suppose it was always going to be hard to step out blinking into the light, but I’ve got a new backing band and we’re preparing the live show now, so that’s going to be great.”

How do you think you’ll present Former Things on the live stage?

“It couldn’t be the same as before when I had a classic line-up with real drums because I got rid of real drums altogether. The record is more of a celebration of drum machines, so I’ll be using a more electronic-oriented setup and stripping things down from a four-piece to a three-piece. I’m currently in the middle of figuring that puzzle out.”

You seem to be slowly phasing guitars out of your music too?

“I’ve wanted to work with electronic hardware for ages and get my hands on a couple of analogue synths. Instead of using the guitar as a writing tool, I used a Doepfer MIDI-analogue sequencer, which completely changed the way I wrote.

"I was mainly connecting it to an ARP Odyssey and Korg MS-10, so they’re at the heart of this album along with multiple drum machines and samplers. I also used the ARP and the Korg to make synth basslines with a little bit of real bass used as a frequency backup.”

You clearly have a love for drum machine rhythms. How’s that evolved over the years?

“I’ve owned this £30 Yamaha keyboard since I was about 10 and it’s appeared on all my albums. It’s got a drum machine pattern bank and I used to spend hours writing songs by pressing play on something called ‘16 beat’, ‘funk’ or ‘disco’ and playing guitar along to them.

"Over the years everything’s evolved from that starting point. I don’t have all the classic drum machines, but we managed to layer real samples from real drum machines like the Roland T-909, 808, 606, the Drumatrix, E-mu Drumulator, Roland CR78, Korg Rhythm 55 and a Linn Drum, so the album’s a joyful smorgasbord of different drum machine textures and percussion, which forms a kind of scaffolding.”

How did you gain access to all those vintage drum machines?

“Bill Skibbe had those, but he’s based in Michigan. I physically went there to finish Hinterland with him and was meant to go out to Detroit to mix this album but the pandemic put paid to that so we had to do everything via Zoom.

Part of me is interested in taking the laptop out of the equation completely

"He had all these drum machines and samples his end, so that’s how we layered up the sounds. I’ve got a modern MFB Tanzbär drum computer and a Roland TR-505, so I programmed and layered all the beats and rhythms and Bill used a trigger that automatically copies the beats to add more to what was already there.

"We had two screens going, one so we could work on Pro Tools sessions at the same time and the other was just his head – a virtual Bill [laughs]. We basically tried to get as close as possible to the two of us sitting together at a desk.”

How does the more modern MFB Tanzbär drum computer compare to the vintage machines?

“The Tanzbär is made by a company in Berlin and has a standalone sequencer. I bought it because it’s got a really harsh techno sound and I’m a fan of techno and electro. Cybotron’s Enter album was very present in my mind when I started writing, so I wanted a machine that sounded really cutting.

"Every drum machine has its own timbre and texture – its own personality. So you can never have too many of them. I’m not too keen on the remodelled classics or the mini ones, but I’m not a snob that only uses classic 909s. I’ve got a really cheap drum machine called a Zoom Micro RhythmTrak MRT-3B that cost £99 and it’s got a great pad bank.”

Are you putting the machines through a lot of outboard or looking to retain their raw sound?

“Retain the raw sound because that’s what I like about them, but I’d love to have more processing units because that’s where a lot of the magic happens. I did use a couple on the album – a vintage Deltalab Effectron II, which has a really cool flange/delay sound, and a cheap Yamaha EMP700 Multi Effects Processor from eBay, which I bought because I discovered it was on the gear list of Richard Kirk from Cabaret Voltaire.

"I do love processing units and would like to get my hands on more of them, but my sound isn’t super-processed. I suppose I’m celebrating the hardware for what it is rather than processing it to the point of obscurity.”

The songs are full of interlocking tones. Does that make it slightly tricky to put too many effects onto it?

“I’ve really gone for it when it comes to the minute details. I used the Roland SPD-20 percussion pad a lot and there are layers and layers of hi-hats and triangle sounds. I’m a fan of detail and think that the interest in my music comes from the gear I use and the way it’s arranged, so there isn’t much room for weird distortions of sounds.”

Do drum patterns form the basis of your songwriting process?

“It nearly always starts off with a beat and me faffing around with a sequencer clocked to a drum machine or sampler that’s got loads of different, cool samples on it.

"I want to work with rhythm in a more efficient and immediate way, generating multiple lines of drums, percussion and melody in sync, which I can do with three channels on the sequencer. I generated a chunk of new music with no vocals and that came out okay, then I created a second wave of music until something cohesive started to evolve.

"This album definitely started off sounding a lot more hard-edged and techno; then I built up layers and layers of arrangements over a long period of time and took them towards my LoneLady sound world.”

(There Is) No Logic is quite symbolic of the album in that it has a sense of simplicity but on closer inspection the mix is quite busy with big attention to sound placement…

“It’s crazy really – making this record nearly killed me. It was a hell of a lot of hard work, but if there’s something wrong in a track, even if it’s one hi-hat, a massive siren goes off in my head and I can’t rest until it’s sorted out.

"Maybe that’s partly why I don’t churn out albums every two years. I could never live with the idea of putting an album out and subsequently thinking, hmm, I wish I’d done this or that. Music for me is like a possession.

"Sometimes I was in Somerset House for six or seven days a week but sometimes I was just watching a Bergman film or taking photographs, so I do think you have to let the music side of your brain rest for a bit and do things that make the soil fertile again.”

The vocals are also cleverly edited and integrated into the mix. A few techniques you used were slightly reminiscent of Paul Hardcastle’s 19 sample style…

“I love the sound of that song and all that stuff was in my mind for No Logic. I don’t sing vocals as a live performance and can never do a take from start to finish. Because I want it just right, I’ll do one sentence or word at a time, so it’s very detailed and exacting.

"That doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have emotion, but the delivery is a lot sharper – even a little R&B as some of the singing is quite fast with clear diction.”

We heard a story that you were lent a synth by Brian Eno. What’s the truth to that?

“I was given a synth by Brian Eno. He was, or still is, a trustee of Somerset House studios and visits from time to time. My studio was very long and thin and, unusually, I had the door unlocked for a change, so one day I saw Marie at the end of this long room standing with a man.

Having surrounded myself with a lot of gear I’ve now got a desire to strip everything back down again

"I was working with an apple core in my hand and when I turned around Brian Eno was stood right in the middle of my very weird higgledy-piggledy studio. I didn’t have time to feel nervous, so we had a chat and he was really friendly and had a little nosey around my equipment, then he remarked that he had too much equipment so I playfully said there’s plenty of room if he wanted me to take some off his hands.

"One week later, a Korg Triton arrived in a parcel at my door. It’s a very crisp and weird digital-sounding beast, so I’d love to know what album Brian used it on, but I found a place for it on the track Time Time Time.”

Do you think you’ll be collaborating with Brian anytime soon?

“We don’t write very similar music do we? I can’t see myself making an ambient music record but if he wanted to produce something I’m doing that would be really interesting. So, yes, I’d love to.”

You were working with modular enthusiast Benge at one point. Did he manage to persuade you to integrate those tools into your sound?

“It depends what you do with those tools. I’ve never had a problem with modular itself but it did suddenly seem like everybody was using modular gear and not doing much with it.

"For me, everything evolves very gradually from album to album – I don’t know what the next one will be, but having surrounded myself with a lot of gear I’ve now got a desire to strip everything back down again.“

It sounds like the detail you put into this album sent you a bit stir crazy and you want to move further away from gear rather than towards it?

“It’s more about where you want to be in your mind, so it’s more of an existential thing. For example, I feel like I get lost in digital plugins and don’t know where I am.

"I’d rather move to it just being me, a guitar and a drum machine and developing the riffs and songs in real time than recording bits and bobs and spending god knows how long sifting through a load of audio on a screen.

"Part of me is interested in taking the laptop out of the equation completely and going back to using a Tascam 4-track cassette recorder, so I might do that.”

LoneLady's new album Former Things is out now on Warp Records.

“A synthesizer that is both easy to use and fun to play whilst maintaining a decent degree of programming depth and flexibility”: PWM Mantis review

“Do you dare to ditch those ‘normal’ beats in favour of hands-on tweaking and extreme sounds? Of course, you do”: Sonicware CyDrums review