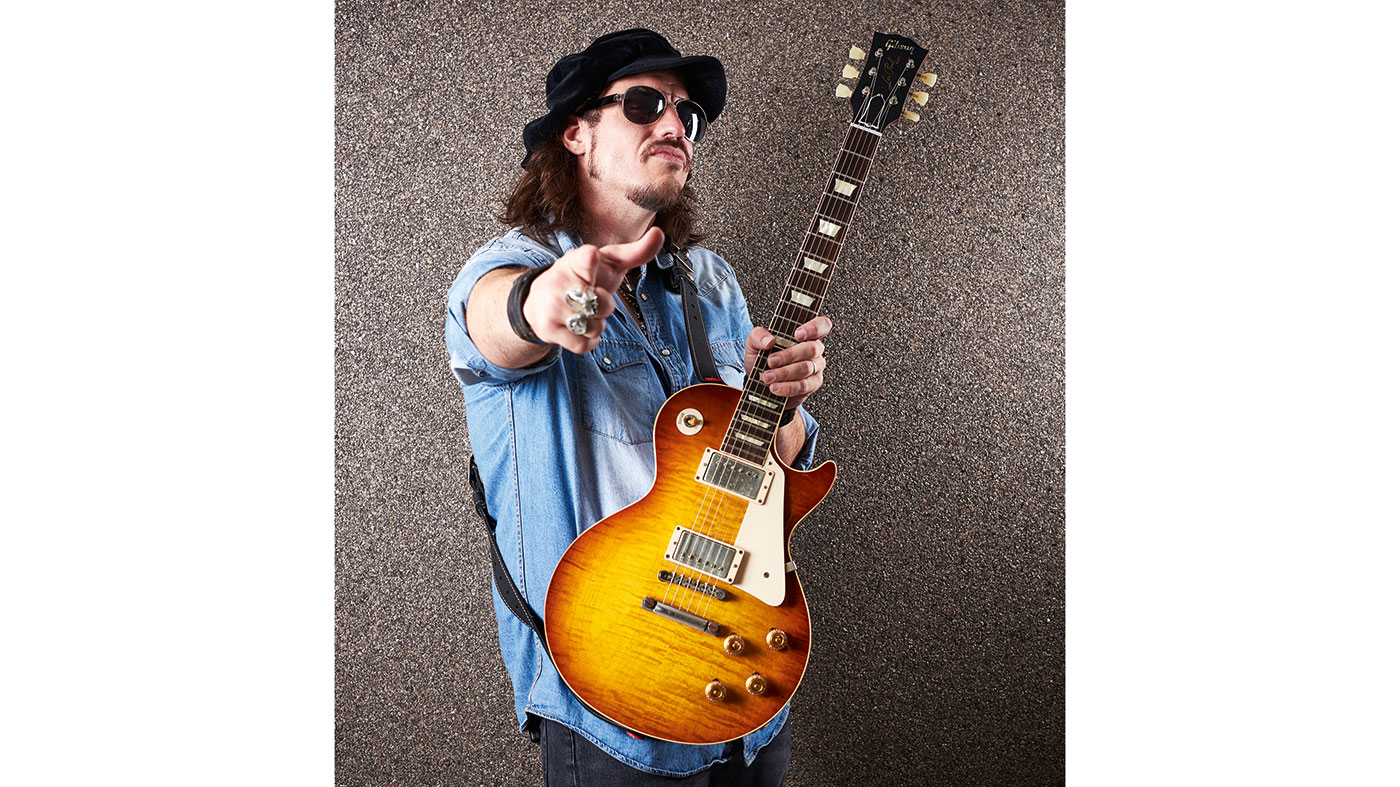

Lance Lopez: “Texas guitar playing is the attitude of putting everything behind each note”

Championed by Billy Gibbons. Mentored by Johnny Winter. Shattered by addiction. The Texas gunslinger tells his story

Lance Lopez wouldn’t wish his lowest ebbs on his worst enemy. The alcoholism that gripped him as he debuted aged 14 in the clubs of New Orleans. The addiction that blighted his role as teenage sideman to the blues titans. The demons that pursued him through a misfiring solo career.

Yet as the 40-year-old Texan reminds us in a rough as asphalt drawl, it’s those same hardships that fed into Tell The Truth: his sixth album that many are tipping as Lopez’s breakthrough, driven by tough, candid songs and fiery Les Paul work that runs with the heritage of his home state. “The underlying theme,” he considers, “is coming out of darkness, back into light.”

Let’s go back to the start. What was the lure of blues?

Growing up in the 80s... Everybody was two-hand tapping, playing Crazy Train; I wanted to play Mississippi Queen

“I remember being five years old, pulling up to a stop light in Louisiana. The window was down, and there was this old black gentleman sitting on the porch playing slide. I remember thinking, ‘This is the greatest thing I’ve heard in my life’. I was always drawn to the players from the late-60s and early-70s: Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Alvin Lee, Leslie West.

“But growing up in the 80s, that wasn’t cool. Everybody was two-hand tapping, playing Crazy Train; I wanted to play Mississippi Queen. But in June 1990, we moved from Louisiana to Texas, and within a week, we saw Stevie Ray Vaughan and BB King jam together in concert. That’s what started it. I went back and studied country blues and Chicago electric blues, got into Robert Johnson, Son House, Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, Magic Sam. All the way, y’know?”

You started in the New Orleans clubs, then backed up Johnnie Taylor, Lucky Peterson, Buddy Miles. What are your memories?

“It was all about being a supporting musician. With Johnnie, we’d back up other artists like Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland, Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, Little Milton. And it was the old school, where if you made a mistake, you got fined $50. Or each wrong note cost $25. Some nights, they’d go, ‘Man, you were so bad, you’re not gonna get paid.’ So if you wanted to eat, you had to be on your game. There was no coddling.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“At 17, it was a great school. Would I ever want to go through it again? No way. Y’know, Eric Gales and I get together and tell stories about that world. Eric came from playing in church, and the African-American churches in the Deep South are almost the same - just without the crazy drugs. There’s not a big difference between the preachers and bandleaders, y’know? They’re both real hard!”

Sounds tough…

“Yeah, but it taught me to be an ensemblist, and everything about rhythm chops, because for many years I was strictly a rhythm player, didn’t play solos at all. Later on, in the blues-rock world, I’d see a lot of guys: all they could do was play lead, and when it came time to play with another guitarist or big band, they were lost.

“That was what drew Buddy Miles and I together. He watched me play with Lucky Peterson and he said, ‘Man, the only way you know those voicings and strumming patterns is you must have played on the Chitlin’ Circuit. You had to have played with Wilson Pickett, Solomon Burke or Johnnie Taylor...’”

Kicking the habit

Were there rough crowds coming up?

“Absolutely. When I was on the Chitlin’ Circuit, those venues were 99 per cent African-American. And here I was, a 17-year-old, long-haired, rock ’n’ roll-looking guitarist. Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson called me ‘young blood’, but Johnnie Taylor just called me ‘white boy’. I don’t think anybody knew my name for months!

“There were several venues - I remember one in Georgia - where they had a sheriff deputy escort me. I had to stay on the bus until it was time and he’d bring me in and stand on the side of the stage.”

The first line of the new album is “nothing worth having ever came easy to me”. What have been the hardest points of your journey?

I was a severe alcoholic. Y’know, I began playing bars in the French quarter of New Orleans aged 14. There was an endless supply

“I was a severe alcoholic. Y’know, I began playing bars in the French quarter of New Orleans aged 14. There was an endless supply of especially alcohol, but also drugs. As I grew up, it was abundantly clear that a lot of the blues musicians I was working with had severe issues. I wanted to be like them, and I’d be right there and partake with them.

“One day, I looked up and I was completely addicted. Cocaine and heroin had just taken a hold of me. I just couldn’t get well. In and out of rehab. Struggling to get clean for so many years. It just ended tragically for me. Then there’s the other side of the story: so many relationships, marriages, girlfriends. It’s the same story you’ve heard a thousand times… but for me it was a personal one.”

You were friends with Johnny Winter. Did he help?

“Yeah. I was on tour with Johnny and struggling really bad with the heroin. Johnny had been a long-time addict, and he had since gotten healthy. One night in Atlantic City, we were sitting on the bus, I was at the table with Johnny and I was visibly high, y’know, nodding from the heroin. And I’ll never forget it. Johnny looked up at me and said, ‘Trying heroin was the stupidest thing I ever did.’ It impacted me so hard. That was a month before I went to rehab.”

How did you finally beat your addictions?

“In 2014, I was contacted by MusiCares. They provided the means to get treatment and saved my life. I’ve been clean ever since. But all through the making of the first Supersonic Blues Machine album [the supergroup of which Lopez is the singer] and Tell The Truth - which started in 2012 - I was struggling. Those albums were the only things that kept me alive, gave me the drive to not just sit around and do drugs. Today, I’ve gotten on top of it, and life is not perfect, but it’s way better than it was.”

The lyrics are certainly powerful. But how did you get such attitude into the guitars?

“On previous albums, I’ve wheeled in big 100-watt Marshalls and 4x12s. We needed a big room to capture the sound, and even then it didn’t translate. With Tell The Truth, we went smaller. We had the Bogner Brixton with 2x12 Marshall cabs: one with Greenbacks and another with Vintage 30s. The approach was to go for lower-wattage, more gain - y’know, as opposed to trying to get the big Marshall stack sound, let’s go with more control.

“We also used a 50-watt Super Dallas head. Derek Trucks and Warren Haynes had been using it. I had a version that Doug Sewell had originally built for me with 6L6s, but Warren and I had dinner one night and he told me, ‘No, you need to send it back and ask for EL34s.’ It came out so fantastic. Then there was the Helios 100, which is basically the platform of a ’68 Super Lead and a mid-60s JTM45. I also used Bogner cabs with Creamback M65 and H75 speakers.”

A Winter's tale

You’re a Les Paul man, right?

“We had a ’58 VOS Custom Shop reissue, and this great Iced Tea ’Burst R9, which is my main guitar now. It was built in 2016 by the Custom Shop and it’s a special guitar. As it was explained to me, the Custom Shop would build one specific Les Paul, taking random specs from each of the signature guitars - y’know, Jimmy Page’s guitar, Billy Gibbons’ guitar, Joe Walsh’s guitar - and they would hide it in a certain series of builds. So they would take the pickup output of Jimmy’s guitar, with the body size of Billy’s, with the top of Don Felder’s - so you would go through a line of Les Pauls, and all of a sudden you’d pick one up and go, ‘My gosh, this is fantastic.’ I think mine is Page’s body, Gibbons’ neck - but we haven’t gone through their actual guitars to A/B, so I’m not real sure. That’s the mystery of that guitar!”

What other Gibson gear did you use?

“The main slide guitar was a modern Firebird. However, we pulled out the pickups, and I had a tech in Dallas wind me two Alnico V Firebird pickups. The bridge read out at 15.5k and the neck at 11.5k. So it didn’t make it hotter, louder or more high-gain - it made it wider, more like a PAF. Cash My Check and Never Came Easy To Me, those slide parts are a ’63 Melody Maker straight into an 80s Marshall Silver Jubilee.

With the slide, I was mentored on the road by Johnny [Winter]. He’d share so many of his licks

“The other Firebird was my ’65 VOS reissue Pelham Blue V, with the Lyre tremolo. I used that on almost the entire Californisoul album from Supersonic Blues Machine, especially for the funky parts. On Tell The Truth, it held the key function of the clean parts. The Alnico V mini-humbuckers were specially wound: they have great sustain and just enough output, yet retain the chime and twang of the classic mini humbucker.

“One of the oddities came in on Blue Moon Rising, where we deviated off into Fender world with a ’63 Tele. It had that Steve Cropper, Stax, R&B kinda thing happening. We also had a PRS DGT Custom on the solo to The Real Deal. Brent Mason - who’s a friend and session player - told me: ‘All of us in Nashville are using those. Just have one handy and you’ll be surprised.’”

How about pedals?

“Mojo Hand has a nice little overdrive called the Rook. Robben Ford turned me onto the Vertex Boost. We had a vintage [TS] 808 Tube Screamer and the Big Joe [B-304] Delay. One of the fun parts was Angel Eyes Of Blue where we actually used an MXR M222 Talk Box. I used an old Fulltone Clyde Standard wah that I bought at Rudy’s Music in New York, many years ago.

“Y’know, I love the old V847. However, I would always break ’em, I was just so tough on ’em. The thing about the Fulltone, I could achieve the tone of the best vintage Voxes - but it had durability for the road. I think some of the best wah tone we got was on the solo from Raise Some Hell.”

Are you a very different guitarist when you play slide?

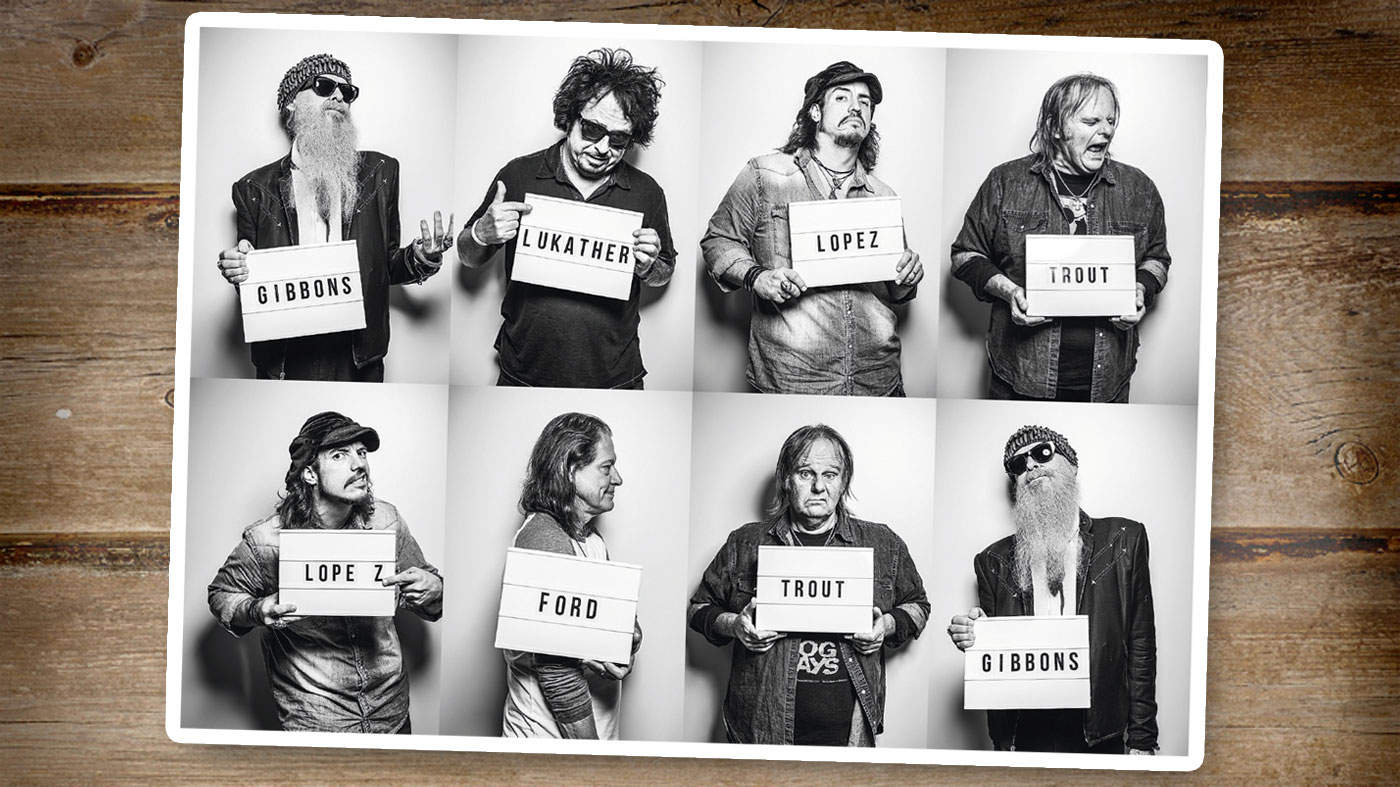

Gibbons, Ford, Lopez, Lukather and Trout talk Supersonic Blues Machine

“Absolutely. Y’know, with the slide, I was mentored on the road by Johnny [Winter]. He’d share so many of his licks, and he always stressed the importance of having open strings in-between the licks. My slide is very traditionalist, because of who I studied with.

“When Johnny imparted that knowledge, it wasn’t a matter of, ‘I need you to keep this going’… but looking back, maybe it was. Y’know, we didn’t think about that until he was gone. With my regular playing, there definitely is a different approach: more patterns, more speed and agility things, in a minor pentatonic scale. I’ve had so many conversations with Billy Gibbons about tone and feel, and making a statement count without too many words.”

The other ingredient, of course, is Texas itself. How does that flavour your playing?

“There’s so many attributes of Texas guitar playing. It’s definitely the attitude of putting everything behind each note. There’s two schools of thought in Texas. We have a traditionalist camp that likes Jimmie Vaughan, then on the other hand, you have Johnny Winter and Stevie Ray Vaughan. I like to get somewhere in the middle.

“I’m a huge blues purist - however, I’m also more of a rock guy. It’s also been a while since we’ve had anybody from Texas playing a Les Paul. For a long time, after Stevie Ray, the Stratocaster dominated. However, it was definitely the nudge from both Johnny and Billy to go back to the Firebird and Les Paul. Our tradition was built on those guitars. So it was good to go back there - and kinda carry that tradition on.”

Tell The Truth is out now on Provogue/Mascot.

“Its mission is simple: unleash the power of any amplifier or line-level source without compromise”: Two Notes promises a “watershed” in tube amp control with the Torpedo Reload II

MusicRadar deals of the week: Enjoy a mind-blowing $600 off a full-fat Gibson Les Paul, £500 off Kirk Hammett's Epiphone Greeny, and so much more