How does delay actually work?

It's one of the most widely used effects for producers, synthesists and guitarists alike, but how does it work?

Of all the various studio processors, delay is one of the most widely used. From a thickening vocal slapback to an echoey synth line, you’d be hard-pressed to find a modern record that doesn’t feature delay or repeating treatments. A delay device stores an incoming signal in its buffer, then plays back a repeat of that stored signal after a predetermined interval.

The first delay units were initially designed to emulate the echoes heard in everyday life, and were famously used to create the short ‘slapback’ guitar effect that defined the rockabilly sound in the ’50s.

Delay vs reverb

Whereas reverb effects use multiple short delay lines to replicate acoustic reflections in a physical space, a delay device stores the input signal in a buffer, then repeats it after an amount of time determined by the ‘time’ parameter. The time can be set in milliseconds, or in the case of software plugins, set in rhythmic divisions (1/4-note, 1/8-note etc) clocked to your DAW’s tempo. Increase the delay’s feedback amount and the delay’s output is fed back into the input, causing the repeats to increase and intensify to create the classic repeating echo effect.

Delay traditionally operates in mono by default, but there’s usually an offset dial for delaying the timing of the repeats between the left and right channels by a few milliseconds – ideal for giving mono sound sources instant, impressive width. Plus, many devices feature a ping-pong mode, whereby each repeat is panned to an alternate side of the stereo field for a bouncing left-to-right effect.

Dry/wet control

With most delay applications, you’ll usually want to hear both the target sound and the delayed signal in the mix. Therefore, if a delay effect is inserted in series over a channel, the dry/wet mix control is used to set the balance between the dry source sound and the repeats.

Alternatively, a common studio technique is to use send/return set-ups: by placing the delay effect on a mixer’s aux return channel, then sending various amounts of multiple mix signals to this single delay, you can share processing resources across the different tracks, and even apply extra effects such as filtering or EQ to the delayed signal in isolation.

But when should you place a delay directly on a signal, or when to use send/returns? Well, the latter offers maximum mixing flexibility, as you have a separate channel containing just the delayed signal, making it easier to level and sculpt the delay on its own, using additional processes such as filtering, EQ and more. This also helps if you need to print your multi-track mix to stems, as you’ll capture the delay signal as a separate audio file, giving more possibilities for editing and processing come mix time.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Also, fading up the delay on a separate channel keeps the dry signal at 100% volume, whereas using an insert delay effect’s dry/wet mix will turn down the dry signal slightly. However, in the current age of super-fast computers and multiple plugin counts, it can be more convenient to throw separate delays across different channels and dial in settings quickly.

Change of tone

Many delays feature onboard low-cut/high-pass and high-cut/low-pass filters for altering the delayed signal’s tone. This simple process can have a big impact upon the effect you’re going for – for example, a low-passed vocal delay can add dark, aged, analogue-style ambience; and extreme high-pass filtering over the same delay might add subtle treble width and sparkling character to the voice.

Best delay plugins 2024: Add depth and dimension to your mixes with these must-have plugins

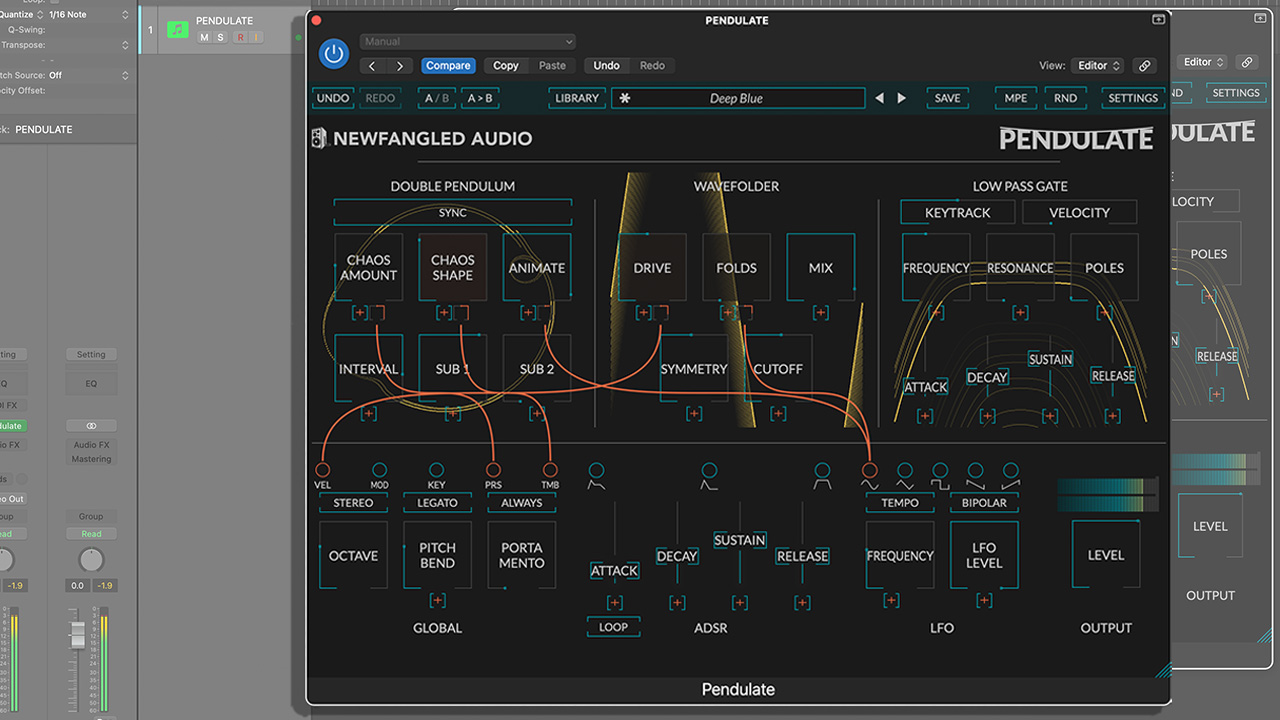

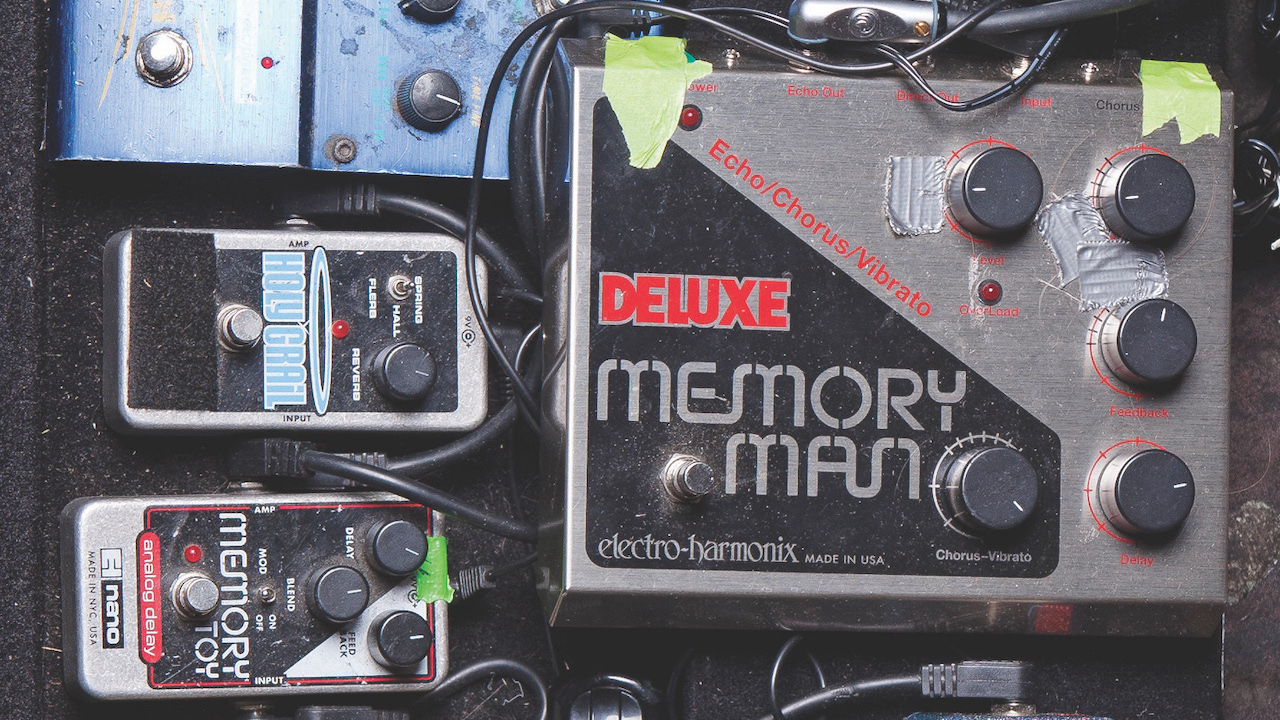

Some delay processors even feature dedicated EQ controls for shaping the delay’s frequencies further. Many delay plug-ins also offer internal saturation stages for dialling in the exact amount of drive; while others allow you to switch between various delay algorithms or modes to emulate specific iconic hardware delay units and pedals such as the Echoplex, Roland Space Echo, and Electro-Harmonix Memory Man.

3 types of classic hardware delay

1. BBD

As ’70s technology advanced, the ‘bucket brigade device’ (BBD) gave birth to the solid-state delay pedal as we know it. This small BBD circuit could store just enough of a signal to generate convincing echo effects, and could be fitted inside a smaller, more convenient, battery-powered chassis such as a stomp box, giving birth to the ubiquitous guitar pedal suitable for the touring guitarist’s gig bag.

BBD echoes are characteristically dark and band-limited, with their extreme 2kHz-ish high-frequency roll-off and maximum 500ms delay time contributing to their restricted yet iconic sound.

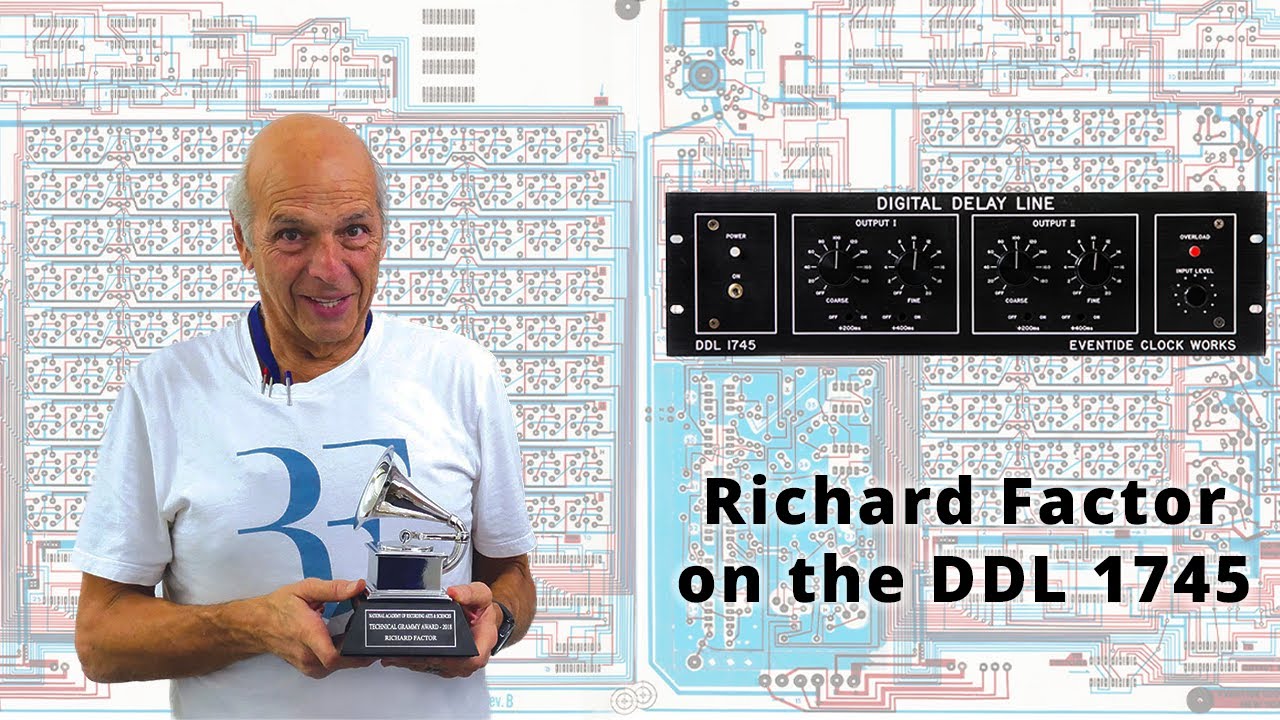

2. Digital delays

Once digital technology came into play in the late ’70s/early ’80s, a cleaner, more full-frequency type of delay effect became the norm. Instead of using mechanical tape or analogue circuitry, the digital delay unit was finally able to loop the input signal in its internal digital memory and spit out mathematically-perfect repeats that never degrade or age over time.

As with most ’80s digital audio technology, this cleanliness was seen as a huge benefit over the old haggard delays of years gone by – but now, funnily enough, we all seek those crusty, dusty repeats, with most digital delays emulating the degradation and ageing of analogue delay.

3. Tape echo

The first studio delay effects used magnetic tape to record the incoming signal and play it back at a momentary interval. Under the hood, an ‘endless’ tape reel is continuously looped, then the incoming signal is recorded onto the tape via a record head and played back by several playback heads.

By altering the tape speed or distance between heads, the time between repeats could be changed, with the former process creating a trippy pitchbending effect synonymous with classic tape delay and early dub reggae effects.

As the tape degrades over time, the delays become ‘aged’, unstable and more lo-fi, giving tape delay its distinctly wobbly, dark sound that’s so sought after in the modern age of full-frequency digital delays. Famous hardware tape delay units such as the Echoplex (1959), Watkins Copicat (1960) and the Roland RE-201 Space Echo (1973).

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.