"People think you just press a button and make a hit song - if it was that easy, everybody would have one": Who will pay the price for AI-generated samples?

We sit down with King Willonius, the "AI storyteller" behind the AI-generated track that ended up at the heart of the Kendrick vs Drake feud

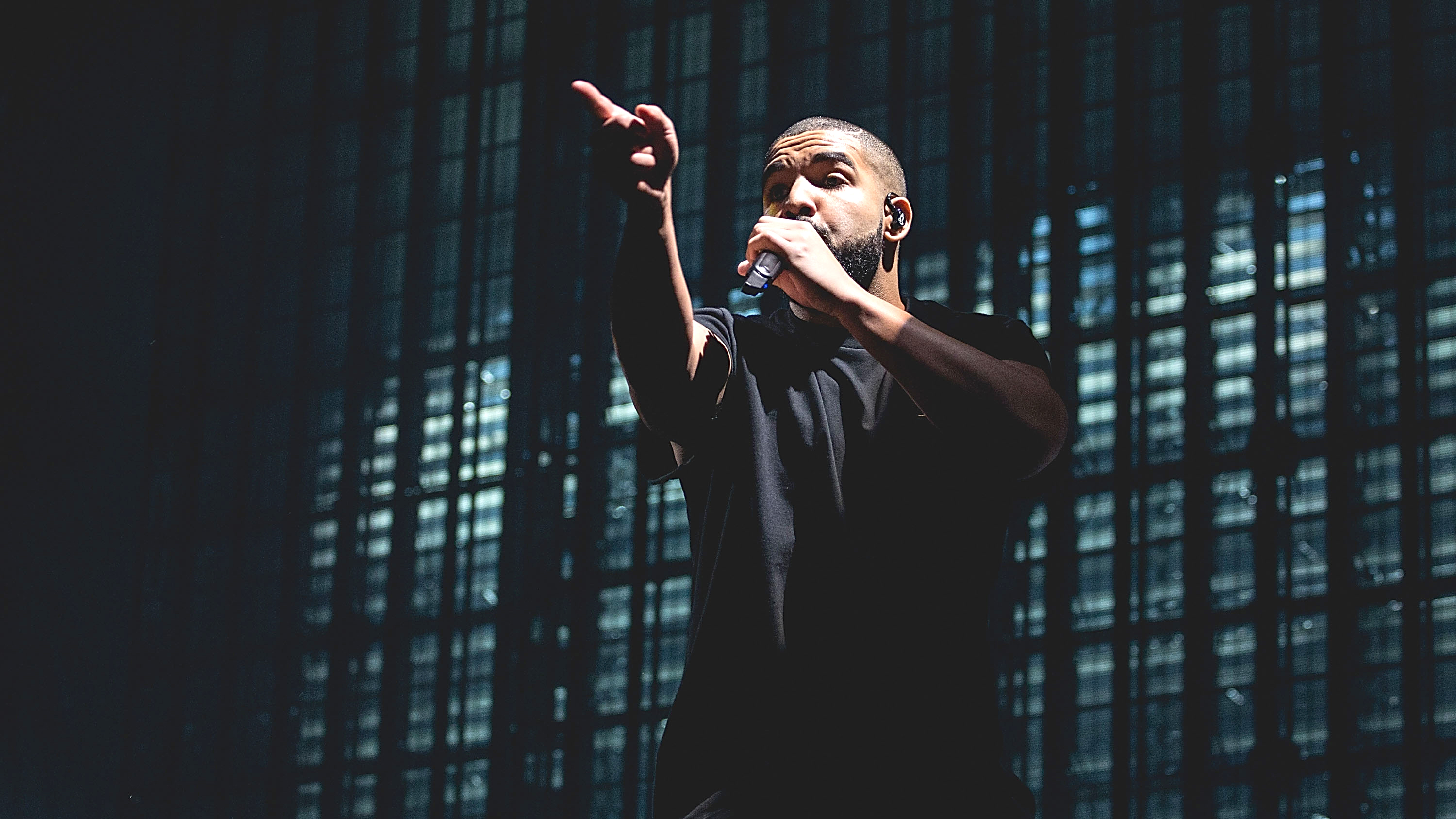

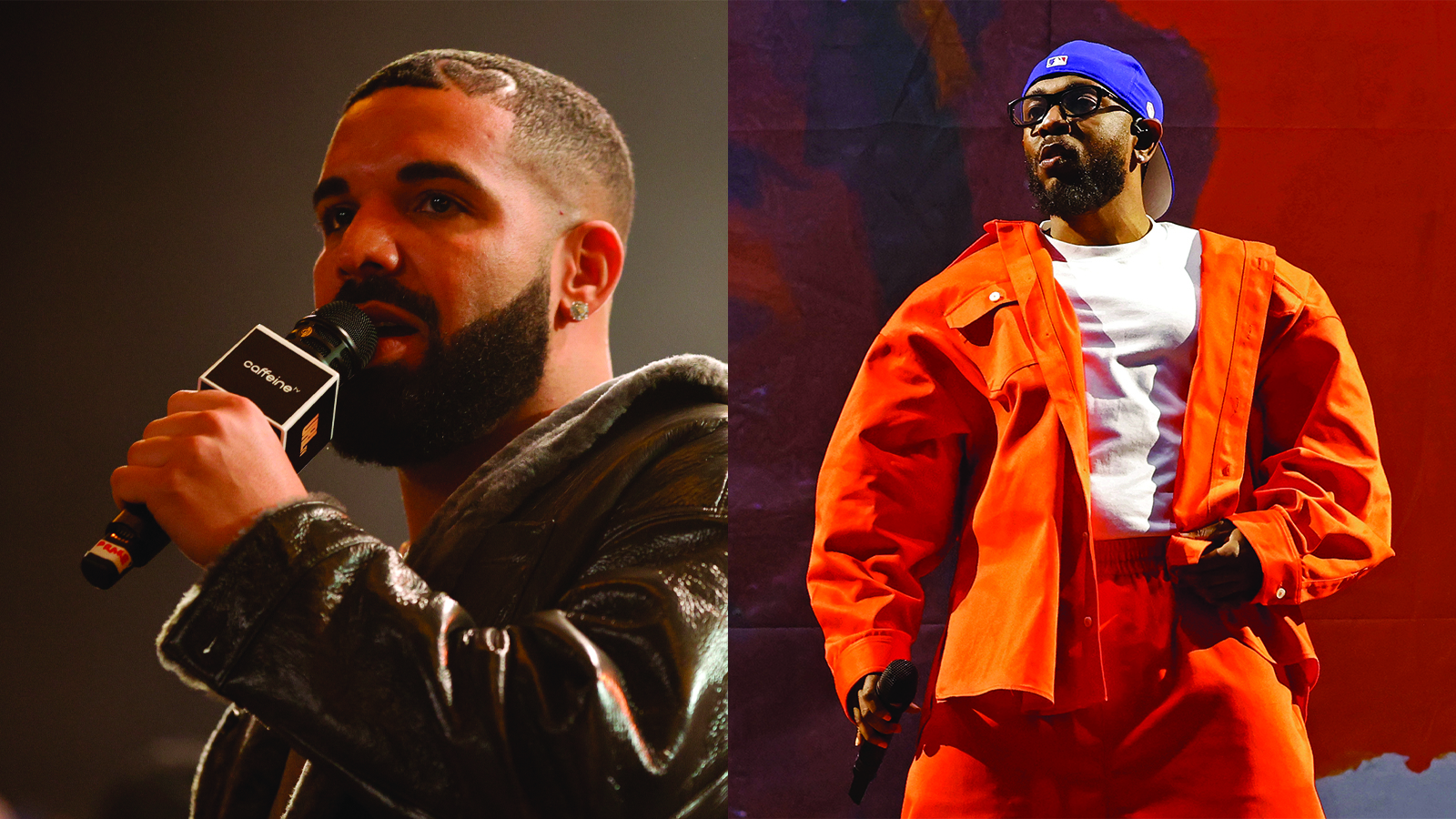

As the closing shots fade out on the feud between Drake and Kendrick Lamar - undoubtedly the biggest hip-hop fallout this side of the year 2000 - another, less ego-fuelled conflict is brewing following producer Metro Boomin’s contribution to the heated exchange.

After grabbing the attention of just about everyone on social media, the track in question, BBL Drizzy, also seems to be causing some stir in the legal professions. That’s because, despite its uncanny resemblance to a soul track straight out of the ‘70s, BBL Drizzy was built around an AI-generated song of the same name, courtesy of the AI content creator King Willonius.

Drake, the intended target of the track, has since sampled it himself in a song called U My Everything, perhaps seeking to take the sting out of the diss. Entertainment value aside, though, with this being yet another chapter in the Drake/Kendrick saga, it’s also been a precedent-setting series of events for the music industry.

BBL Drizzy seems to be one of the first seriously viral AI-generated tracks from a known artist and, with Drake’s official release of U My Everything on streaming services, it now appears to be one of the first forced to navigate the world of copyright law.

How AI is being weaponized in Drake and Kendrick Lamar's rap beef

According to Donal Woodard, Willonius’ legal aid, the master recording of Willonius’ BBL Drizzy is considered “public domain” and not subject to copyright, though the track's lyrics are being credited to Willonius. He reportedly used AI-powered music generator Udio to create BBL Drizzy in the first instance, and artists are increasingly exploring and experimenting with other AI music tools.

This raises the question of what it means to own a piece of music generated by AI. On the one hand, much of the work has been shifted from the musician to the technology - think chord progressions or drum patterns created at the beck and call of a chatbot.

Some may feel that this undermines the creative rights a musician has over a piece of music - if it was the AI that created the music and not the musician, then should the musician really get any credit?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

What about the rightsholders behind the music that the AI was trained on? Many have speculated that platforms like Udio have been trained on vast amounts of copyrighted music; the world's biggest record companies are currently suing Udio and Suno, another AI song generator, alleging that the platforms have exploited the recorded works of their artists.

On the other hand, AI is only a technological tool and, in many ways, not all that different from the DAWs most of us use as standard today. And, much like a DAW, AI requires technical skill and understanding to utilize it. In order to get the desired output from an AI system, a user must know how to operate that system.

"It gives you a baseline of what the song will potentially be, and then from there, you have to keep rolling and extending it to get the sound that you actually want"

Willonius’ certainly seems to have put in the work behind the scenes, telling MusicRadar that there’s still a complex process to go through when creating an AI-generated song. After writing the lyrics, Willonius said, it was then a process of going into the platform to start crafting the prompts. “It's a lot of … trial and error,” he says.

“It gives you a baseline of what the song will potentially be, and then from there, you have to keep rolling and extending it to get the sound that you actually want,” he adds. Willonius rather quaintly likens the process to making a stew. You have your ingredients and then you add in your seasoning, a “little bit” here and there to make sure you get the right end product.

At the end of the day, it’s a creative process, and there are parallels to be drawn to other technologies previously seen as disruptive or downright threatening in the music industry. As Scott Keniley tells us: “Pro Tools and computers and laptops came about, and now you've got people in a room that don't need musicians”.

Keniley, the chief legal officer (CLO) at Soundscape and senior partner at law firm Keniley-Kumar, says that, while this changed music creation, it far from eliminated creativity.

“It's the art of using Pro Tools” that matters, Keniley says. Just because there are new forms of technology available, does that mean “that me or you can go in there and to do the same thing that a Mike Will does? … We don't know how to use the technology like they’ve perfected”.

“They've learned how to warp and alter the samples, they've learned how to do MIDI rolls and drop in plugins, they've learned how to do all these different things,” he added.

“I put in my 10,000 hours perfecting my craft”

There’s a narrative going around, Willonius says, that AI music generation is “super easy,” that all a musician needs to do is “press a button” and make a hit song. If that were the case, Willonius says, then “everybody would have one”. In reality, the process isn’t as simple, he says, and Willonius wants to make sure people know this - “I put in my 10,000 hours, perfecting my craft”.

Copyright is a different story, of course. The legal structures which exist around the monetization of musical creations are complex, and decisions won’t be made quickly. Take the case of computer scientist Stephen Thaler who has been arguing that copyright should apply to AI-generated works, a legal process which Keniley brings up in our chat.

The courts have rejected Thaler’s case on the ground that human authorship is required for copyright protection. As Keniley suggested, however, this does not entirely reject the idea that AI-generated content can be copyrighted. The court has not rejected that a human could own a copyright for AI generated content, but rather it has rejected that the AI system itself can own the copyright.

While the Thaler case rested upon this question, Keniley thinks that the industry as a whole is headed for a level of copyright protection in the area of AI-generated content.

It takes a human to “create” a piece of music using AI, Keniley said. The question will come down to the prompts that were used, the amount of prompts that were used, the extent to which the musician in control of the software asked the AI to generate more instruments and so on.

“I think the person who designs it - who actually creates this thing - I think they're going to own it,” he added. “And I think there are gonna be copyrights. Eventually, I think they're gonna come around.”

Willonius echoes these sentiments, or at least hopes that the conversation will change. “I definitely want to see a world where … the things that you create or imagine, you can monetize. I think that'd be a good thing.” Willonius said.

So while King Willonius is only receiving payment for his contribution to the lyrics, there may well be a future around the corner in which he owns his AI-generated content outright - whether or not it gets used to poke fun at a platinum-selling recording artist.

Though a full-time tech journalist at ITPro, George Fitzmaurice finds time to indulge his love for music by writing up the occasional piece for MusicRadar. When he’s not keying in a drum pattern on FL Studio or (infrequently) practicing the guitar, George enjoys finding hidden gems on Spotify and going to live shows.