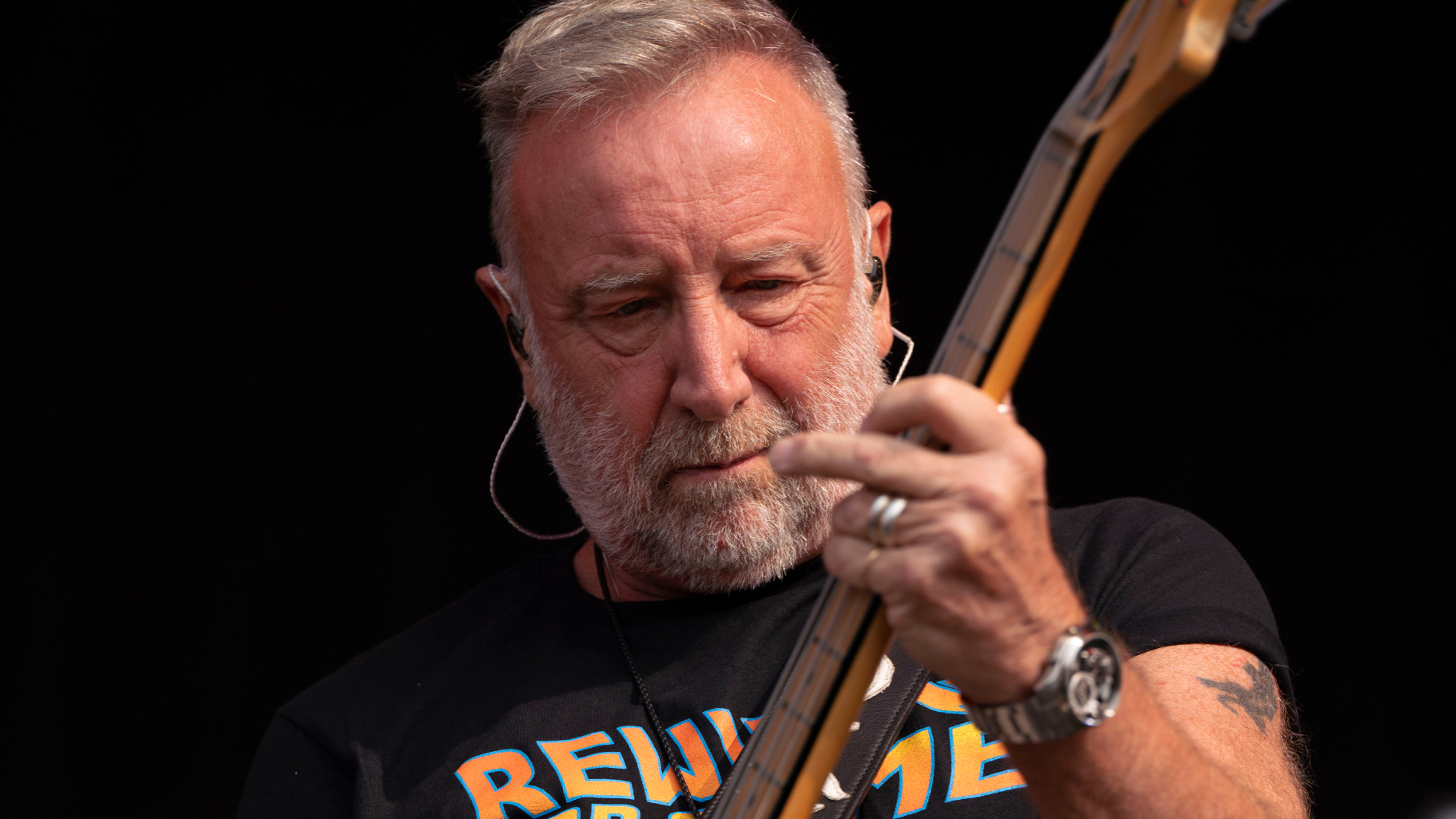

Kenny Passarelli: “I learned a lot from Stephen Stills about playing bass”

The CSN and Stephen Stills bassist reflects

Kenny Passarelli is a bass veteran, having supplied the low end for artists such as Stephen Stills, Elton John and Yusuf Islam over the last five decades. Here he recalls a particularly pivotal moment with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young...

“I was a classically trained trumpet player from the age of seven until I peaked out at 14. I had all this Bach and Haydn, and I was on my way to playing in major orchestras, but then the British Invasion happened. Popular music changed, and all of a sudden I was totally into the whole thing. Some guys in my high school bought guitars, and nobody wanted to play bass; everybody was on lead guitar or drums.

I got to hear the acetate of the Crosby, Stills & Nash record in probably March of 1969. It blew my mind

“My parents got a little Spanish guitar and I taught myself how to play bass with the first four strings. If you already have training in one instrument and you want bad, you can assimilate a new instrument very quickly. I became quite proficient on the bass right away because I practised so much and I was playing all the time.

“Before I knew it, I bought myself my first bass, and by eleventh grade, I was in a band, playing on weekends in Denver. A blue Mosrite was one of the first basses I played, but it was too much like a guitar, so I bought a Gibson EB-3, the red semi- hollowbody. After my first year of college, I got into another band called The Beast and we got a deal with Atco.

“Somebody in town who knew me as a bass player said, ‘Stephen Stills is coming to town. Are you hip to it?’ I said ‘Yeah’ because I saw the Buffalo Springfield when they came through Denver and I was blown away. I was a big fan of Stephen’s, so we met in the mountains in Colorado, and I got to hear the acetate of the Crosby, Stills & Nash record in probably March of 1969. It blew my mind. I sat with him, he played me his acetate, and when I heard Suite: Judy Blue Eyes it changed my whole life. I’d never heard anything like it.

“He said, ‘What kind of bass are you playing?’ I said ‘I play a Gibson’. He took out his bass, the original bass on Suite: Judy Blue Eyes, which is a ‘61 Fender P-Bass, and he said, ‘This is what you’ve got to play. This is the sound. You’ve got to do this.’ So that was it. From then on, I played Fender, but I immediately got a Jazz because I felt it was better for me. When I started working with Elton John, I got some more P-Basses in London, and that’s what I used with Elton on the Wembley Stadium gig and at Dodger Stadium. I play four-strings. So many other people are playing the five- string, but I didn’t make that switch.”

Back together

“By 1974, I’m working with Stephen, we did Carnegie Hall, we’ve done the Stills record [released 1975], we’ve done the live record from Chicago [Stephen Stills Live, also 1975] - which is a great recording in many ways; not mixed great, but it’s a great performance - and Stephen said to me, ‘Crosby, Nash, Stills & Young are going to get back together again, and if you work with me, you’ll get that gig.’

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“So we’re rehearsing up there at the ranch. I can’t believe it’s finally happening, and I’ll be damned if Stephen pulls me aside and says, ‘Graham [Nash] and David [Crosby] think you’re too young for this gig’. [Passarelli was 24 at the time - Ed.] I just couldn’t believe it, because I’d rehearsed with them and it sounded incredible, I was playing a guitar in one of their houses, and they were all standing around. It seemed like the perfect time to confront Graham and David. I said, ‘What do you mean, I’m too young?’ And they looked at me like, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about’.

The bottom line is that Stephen was one of my big teachers

“Little did I know that [late, acclaimed bassist] Tim Drummond had been promised the gig by Neil. I guess they decided, ‘We’ll let Stephen come up, but it’s not going to happen’. We go to rehearse, and Neil had a different plan. I didn’t know it until 30 years later when I read Neil’s book, Shakey. I happened to just open it up and there was my name: ‘Kenny Passarelli was Stephen’s guy for bass, but I wanted Tim Drummond’. That was the first time I really knew the truth. I was never told until then.

“I finally did get the chance to play in ‘83 with CSN, but never with CSNY. Neil came a couple of times, and then I did work with Stephen and Neil a couple of times. I went to Europe with them, but David, even though he could still sing, was really into the depths of his debauchery with his drug addiction at the time, which didn’t make it easy on everybody. But the gigs were really good. He was incredible. I can’t say any more about how this guy still could sing.

“Anyway, the bottom line is that Stephen was one of my big teachers. I learned a lot from Stephen about playing bass. He really taught me a lot. He could be kind of abusive, but I was so close to him that I understood his aggressive tendencies. You add a bunch of blow and scotch and you’ve got a monster. He’s got a bad reputation for going off on people, but he’s a genius, there’s no doubt. He’s definitely one of the smartest and most brilliant. At his time, nobody could touch him. I really think that nobody could touch this guy. He had it all, man. He could play acoustic, he could play electric, he could play drums, he could play keyboards. He was absolutely the best. I was originally going to play at Woodstock with him, but again, Neil Young always had a different angle. I get along with him, but he was always a guy that was in the way of me working with CSNY.

“I produce a lot nowadays. I started producing back in the mid-90s. I started with a blues artist by the name of Otis Taylor. I launched his career. I did five of his first CDs and got a bunch of attention for him, went back and forth to Europe. From there I moved on and produced his guitar player named Eddie Turner. There’s another writer by the name of David Jacobs-Strain, kind of a prodigy, and I did about five CDs with him. So I’m busy, and life is good.”

“I’m beyond excited to introduce the next evolution of the MT15”: PRS announces refresh of tube amp lineup with the all-new Archon Classic and a high-gain power-up for the Mark Tremonti lunchbox head

“These guitars travel around the world and they need to be road ready”: Jackson gives Misha Mansoor’s Juggernaut a new lick of paint, an ebony fingerboard and upgrades to stainless steel frets in signature model refresh

![PRS Archon Classic and Mark Tremonti MT 15 v2: the newly redesigned tube amps offer a host of new features and tones, with the Alter Bridge guitarist's new lunchbox head [right] featuring the Overdrive channel from his MT 100 head, and there's a half-power switch, too.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/FD37q5pRLCQDhCpT8y94Zi.jpg)