"The idea was that the computer would give us more time for creativity, but it was just the opposite...": Kraftwerk's Karl Bartos on how technology curbed the band's creativity

Ex-Kraftwerk member Karl Bartos on the backstory of his new soundtrack to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

We last spoke with Karl Bartos some 10 years ago for the release of his wonderful trawl through his own musical archives, Off The Record. For those of us of a certain age, Kraftwerk were arguably the gateway drug when it came to all of the electronic music that followed.

Bartos was a pivotal member of the ground-breaking German band for 15 years, contributing to what are considered all of their classic albums until leaving in 1990, frustrated at the band’s prolonged creative stasis. His recent autobiography The Sound of the Machine: My Life in Kraftwerk and Beyond is essential reading.

Post-Kraftwerk, Bartos formed Elektric Music, releasing two albums before collaborating with Bernard Sumner and Johnny Marr on their electronic project as well as also working with OMD’s Andy McCluskey. In 2021, he was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as part of Kraftwerk’s classic line-up.

The Cabinet of Dr Caligari has been a long-time labour of love for Bartos and the soundtrack itself is a product of a two-year-long creative flow between his Hamburg studio and the Düsseldorf studio of his friend and engineer, Mathias Black. According to Black, the pair “used FaceTime, screen sharing and, for file share, a cloud server. It cannot substitute working together in one studio, but it helps”.

The resultant album is an intoxicating fusion of the orchestral and the electronic; it beggars belief that this is Karl Bartos’ first foray proper into soundtrack work (having previously contributed to Kraftwerk’s track Metropolis, which was a paean to Fritz Lang’s movie of the same name).

We relished the opportunity to excitedly chat music and philosophy with the delightful Mr Bartos, over at his minimalist studio in Hamburg (as well as hearing more about his surprisingly cautious attitude to computers).

Incredible to discover that this is your first ever soundtrack project. How did composing this music for Dr Caligari differ from putting together a new album of songs?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“The difference in creating a soundtrack is that, like dance music, it’s functional music… it’s made for a reason that people on a dancefloor move their bodies to it. The same applies to film music. Some music, for instance, Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring was composed for a ballet.

"During the process of composing for this movie, I considered the movement of the actors as a ballet so, of course, the music has to fit their movements. It’s a reverse process of choreography. The process of writing a film score is very stressful; you don’t have much time, and someone will tell you to make it a certain way, but I chose to do this for Dr Caligari as I needed this movie in my autobiography.”

When we last spoke for the release of your solo album, Off The Record, you’d trawled your personal audio archive for material to work on. Did you do something similar for putting the soundtrack together?

“Actually, that’s a good question, as I incorporated some of the music I wrote when I was a student at the Rhineland State Conservatory of Music during the counterpoint lessons. So I put it all together with my musical partner Mathias Black. One of the reasons I wanted so much to do this soundtrack was because the film was almost like the big bang of pop culture.

"The character Cesare almost looks like David Bowie [laughs] or the predecessor of David Bowie, I guess. I have a lot of living that I still want to do and a lot of music still in my head, so I must bring it out.”

Did the warm critical reception that Off The Record received surprise you?

“Yes, and it’s steadily grown over the years too. Initially, I think it was slow to take off because we didn’t play live. I dont have a band, so we couldn’t do any live shows. So, it took quite a while, but even now it’s getting bigger and bigger.”

Are there still lots of musical delights to be extracted from the archive, and has the digital domain made storing everything too convenient?

“Yes, but for storing and administration the computer is perfect [laughs] which is almost the only thing!”

In your early days with Kraftwerk did you ever imagine a time when you could effectively have a functional music studio in the palm of your hand?

“No, not really. When we came up with the idea of making an album called Computer World, I always compare it to the book Neuromancer by William Gibson, which was written on a typewriter; analogue. The things he was imagining in his head were so far ahead of the time. So, when we did Computer World we had a Moog synth, an ARP synth and a 16-step sequencer but we had the image in our head. We couldn’t have imagined that in 2023 you could, in theory, reach everyone in this world with your music via a mobile phone.”

Do you think young artists and producers who started making music on Reason or Ableton Live have any idea of how difficult it was back then to even get two electronic machines to sync to each other?

“A few years back I had a professorship of the arts at the University of the Arts in Berlin, and some of the students were just DJs. Some of them came up with the idea that everything they would need to rely on was in their laptops. That really took me by surprise at the time. Usually when we had a new semester, we would go to the rehearsal for a symphony concert.

"I remember the first one we went to was with Sir Simon Rattle and, after watching the concert we sat outside the Berlin Philharmonie hall with some music scores, and I explained to them how similar a score is to a computer screen – the main difference being that a score doesn’t playback. So, you have to know how to write notes and use your imagination to put all the blocks together.”

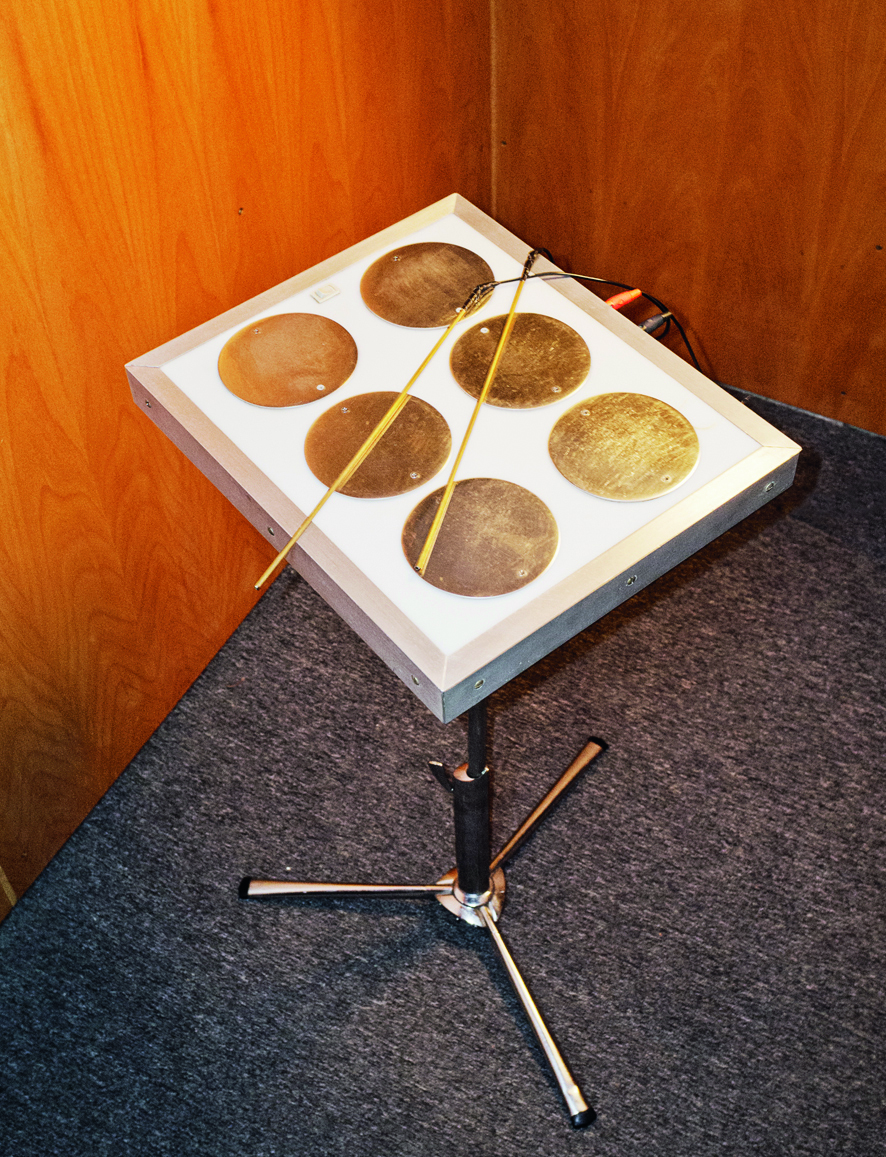

What bits of gear have you utilised in your studio for the Caligari album?

“Well, over there is an original Polymoog and it’s still working! A lot of the music on the album was made with the Polymoog. I work from this studio in Hamburg and my musical partner Mathias (Black) has his studio in Düsseldorf, and sometimes he comes crawling into my computer from there.

"He sometimes helps me with all the technology when it gets too complicated with the computer, as my brain is used to more abstract things like music. Computers always make you feel like you have problems to solve. It’s so anti-creative, so I get Mathias to help with it, and he’s also a good musician, which helps.”

So, you think computers in the music-making process can potentially create as many problems as they solve?

“Sometimes I get the feeling that music culture today is made by computer scientists, because you need to always fill in a form. So, I had to fill the forms while making Caligari even though Caligari was composed in my head, and the piano is supporting the imagination and my Martin D28 acoustic.

"So, I work on the idea, write it down, and then I turn to the computer. In the early days of Kraftwerk we had a tape machine, and now I basically use the computer just as a recording tool.”

Do you carry any portable devices around with you for capturing ideas in transit?

“No… I made an observation that, if I have an idea for a song, I take my guitar and sing along with it, and I don’t record it. I don’t even write it down. Then, next time I pick up the guitar, my subconscious will add something. Chords are the bricks of pop music, so I play some of these brick-chords and my subconscious fills in the gaps. That way it’s not planned and it comes up from somewhere in my soul…[laughs] or from my stomach!

"It just appears, and I have no idea where it comes from. I don’t even write this second idea down. I have some songs for the next musical project I’m working on that I haven’t written down. I have a few lyrics and sometimes I’ll write down some chord changes – just like Paul McCartney did in the beginning, or at least that’s what he always says.”

Your computer is far from a musical hub for you, then?

“You have to keep this process going and you have to remember what you did before. With a computer, it plays every little idea back to you… why? I just want to fill in the blank tape in my mind, not in reality. The process of creativity is not like filling in a form. It’s more about observing the world and nature and trying to imitate that, put it into art and interpret human feelings.

Sometimes I get the feeling that music culture today is made by computer scientists because you need to always fill in a form

"If I do this, then I don’t want to hear it again from the computer. I want to explore, and find the next generation of the chord. Then I play it the next day, and my brain comes up with another chord. You have to always keep in mind the act of creation, which is about an idea, isn’t it? The question shouldn’t be what I have in the studio or what equipment I’m going to use, the question is, ‘what do I need?’ It’s a fight between idea and reality… always, to put my idea into reality.”

We remember last time we talked, we discussed how easy it is to get swamped by options amidst all the new technology. Is that still relevant for you?

“That’s why I reinvented this procedure of not recording something but developing it. Again, like Paul McCartney said in his last book, he’d go over to John’s and there was a coming together of creativity, and they’d come up with an idea. Next day they’d return and if they couldn’t remember the idea, then it wasn’t any good.”

It’s like a filter?

In the beginning we often called our studio an electronic garden, but that garden developed into a factory farm

“Yeah it’s a brain filter and if you can’t remember, then forget it. If you can remember, then next day, something else pops up; the bridge, the chorus or the words, whatever. If you write pop music then, of course, you have to have words. They have to put your everyday life into poetics. Unfortunately, this wonderful machine, the computer, has employed so many administration tools that you’re always distracted by them. So, you have to always remember how to turn off the computer.”

That ethos is certainly in keeping with a growing trend at the moment to take music-making back outside of the box...

“It’s pretty much a dead-end street. Ray Davies said in Waterloo Sunset, ‘every day I look at the world from my window’ and then he says what he sees. That’s exactly what you do if you’re a composer. You look at the outside world and you try to transpose what you see into music.

"With Kraftwerk, we had that concept of the man machine, which was taken from Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis about the female robot called Futura, but we (Kraftwerk) were playing together in a room and looking each other in the eye. We put our communication into music. The turning point for us was digitalisation, and when Kraftwerk became an institution we stopped being contemporary [laughs]. Instead we became salesmen of nostalgia.

The turning point for us was digitalisation, and when Kraftwerk became an institution we stopped being contemporary

“You know, when the computer turned up it was the dream of a businessman. In the beginning we often called our studio an electronic garden, but that garden developed into a factory farming industry. When we wrote Computer World we were still human beings playing together.

"We were playing with the Music and Rhythm Laboratory sequencer, aka the Friend-Chip “Mr. Lab” – Kraftwerk also used the Synthanorma Sequenzer around this time, but the computer came and turned us into a musical box. We became a musical box and also our brains became digitised. We spent all of our time solving problems with technology.”

What equipment do you have at your disposal in your Hamburg studio?

“I have many computers. For the Caligari project Mathias and I worked with Logic Pro on a Mac Pro each, with every plugin available like Organteq, Vienna Symphonic Library, Waves and hardware from Neve, Tubetech, BSS, Lexicon, Sony.”

Would we be right in thinking that you have a trove of desirable old synths in storage too?

“I still have my two Minimoogs, the Polymoog, ARP-Odyssey, Korg PS-3100, Ms-20, Ms-50, Roland MC-202, TB-303. Some diverse keyboards like the Roland D-50, Yamaha DX-7, Nord Electro, Virus B, Novation and others. They all sound great, but then you have to go into the virtual space for the production. All the analogue gear is recorded into the digital space, and this is the confusion again.

"With Kraftwerk, we’d turn up at the studio and start playing and we’d have an aim. Or we’d even just celebrate the improvisation. We’d talk to each other, have fun, look each other in the eye and transfer all that into music. That was the whole secret! The idea was that the computer would give us more time for creativity, but it was just the opposite. We spent too much time with the organisation of sound and with the computer technology. The human beings were not at the centre of everything, the computer was. And we were serving the computer industry.”

So, ironically, the computer impacted negatively on Kraftwerk’s music process?

“Yeah, we didn’t speak to each other and there were many engineers coming into the studio. It’s like every business now thinks they need a computer. It’s not true, but the industry is so clever that they’re selling their computers to everybody… to shops and schoolkids. They all think that this is our future but that’s not true, as the future is what we make it.

"Some of my partners in Kraftwerk believed so much that it was progress, but I actually couldn’t follow that. I think innovation and progress are not synonyms. Would you consider the machine-gun or the atomic bomb as being progress for human beings? I’m not so sure about that.”

This seems like a perfect point to ask for your thoughts on AI in music?

“It’s overestimated, I think. It’s just an archive of human logic. So, if you were to remix The Gutenberg Galaxy [Marshall McLuhan’s revered book from the early ’60s], the Mona Lisa and the Goldberg Variations, what would we get with copy and paste? I don’t know! I think it’s a wet dream from some of those guys in Silicon Valley. They’re really clever at selling us AI… where’s the results?”

You’ll be playing some live screenings of Dr Caligari in the near future. How will you go about presenting the music for those?

“Mathias will be playing alongside me. He’s my friend and my musical partner. I don’t know if you’ve seen any footage of Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry performing their musique concrete? Where they used tape machines, we have the computer, because the foundation of the sound is the symphonic orchestra, and then Mathias and I play along. So, Mathias is doing what Stockhausen referred to as ‘sound direction’. There are so many musical things to be excited about just now.”