Junkie XL on soundtracks, Elvis and how we've never had it so good

We have a little more conversation with DJ turned soundtrack composer Tom Holkenborg

It’s not often that Elvis Presley gets a mention in the Tech section of MusicRadar, but in 2002, the Presley estate finally allowed one of the King’s tracks to be given a club-friendly remix, complete with chunky loops, beefed-up bottom end and the occasional squealing synth.

It was put together by Dutch DJ and producer Tom Holkenborg - aka Junkie XL, aka JXL - who took it to Number 1 in 24 countries.

“As far as hit singles go, this was about as big as it could get,” remembers Holkenborg. “Everybody around me was saying, ‘You gotta follow this up, you need another hit single. This is your time’.”

But much as he appreciated the opportunities that the Elvis remix had punted his way, Holkenborg wasn’t the least bit interested in a follow-up.

“I felt that I’d taken club music and electronic music as far as I could take it,” he explains. “So I shut down my Amsterdam studio, stuffed my laptop into a suitcase and moved to LA. All I could think about was being a film composer - that was my dream.

“My manager almost had a heart attack. ‘What are you doing? Are you crazy? Let’s write another hit single!’ Sometimes, you have to listen that voice inside your heart… even if it means walking away from a big pay cheque.”

It turns out that Holkenborg made the right decision. Still based in LA, he’s now one of Hollywood’s most in-demands composers, adding his name to Deadpool, Mad Max: Fury Road and Wonder Woman, and working with Hans Zimmer on a string of box office blockbusters including The Dark Knight Rises and Man of Steel.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Then there’s commercial work for Nike, Adidas and Cadillac; video games Darkspore and FIFA, and even the occasional club remix. He was nominated for a Grammy in 2008, after reworking Madonna’s 4 Minutes.

He still releases artist albums, too - 2012’s very melodic Synthesized - but these days, Holkenborg spends almost all his time locking music to pictures, and has already released two soundtrack albums this year: Brimstone and the Idris Elba/Matthew McConaughey-driven take on Stephen King’s The Dark Tower.

Was it a difficult decision to walk away from a massive hit like A Little Less Conversation?

“Of course. But I’d already fallen in love with film, and I knew that was the only direction I could take.

“There’s a huge amount of energy in club music, but let’s be honest here, if you take away the kick drum from a club tune, what are you actually left with? Most of the music I was making back then was geared towards clubs and festivals, which means there’s a certain type of harmonic, melodic and rhythmic language that you work with. I wanted to find out what was beyond that language.

“Some people might say, ‘They’re both types of music. Surely, it’s the same job’. Yes, they’re both types of music, but that’s where the similarities end. With film, you’re stretching far beyond a three-minute pop song or a ten-minute remix. Composing is storytelling - you’re making a film with music.”

Prior to the Elvis hit, you had an impressive production CV and you’d already dabbled with soundtracks, but did Hollywood take you seriously? Were the studios willing to take a chance on the bloke who’d just introduced Elvis to the dancefloor?

“It’s like you’ve just won a gold medal at the Olympics for the marathon, and suddenly you say, ‘I don’t want to run marathons anymore, I’m gonna play hockey’. Everyone knows that you’re a sportsman, but the hockey world is gonna say, ‘Who does this guy think he is?’.

“As far as the film world was concerned, I was a nobody. OK, I’d just had a big hit, but I had to go right back to the bottom of the ladder. I started out by working as an assistant to other composers, taking small steps and trying to learn as much as I could.

“I was classically trained [by his mother], which was an advantage… sort of. What I mean is that, yes, I knew about orchestration and writing for strings, but that alone is not going to get you very far. All it did was make me realise how little I knew and how much more I had to learn.

But then along came artist like Vangelis and Harold Faltermeyer. Suddenly, you could create a soundtrack with machines and electronics.

“And let’s not forget that film composing isn’t just about orchestras and conducting. In the past, that was certainly the case - you had a big orchestra and it was all recorded live. It was very similar to the world of classical music.

“But then along came artist like Vangelis and Harold Faltermeyer. Suddenly, you could create a soundtrack with machines and electronics. It didn’t matter so much if you were a master musician, you just needed a great set of ears, some good ideas and the ability to tell a story.

“If somebody wants Aphex Twin to compose a film soundtrack, do they care if he’s classically trained? Or Trent Reznor. Atticus Ross. Radiohead. Chemical Brothers. Underworld…

“To go back to my original point, yes, I am classically trained, and maybe that has been an advantage because I can shift between the two worlds: the traditional world and the electronic world. I can bring together all these different influences and, hopefully, I can find my own voice somewhere in that mix.”

Even though club tunes and film scores exist in different worlds and do different jobs, are there any similarities in the actual compositional process? Both might start with a drum loop or a synth hook…

“The biggest and most basic difference is ego. If I’m writing a track for one of my own albums, the only opinion that matters is mine. I’m making that music for me. With a film soundtrack, you have to let go, because you’re not the one who’s steering the ship. The guy in charge is the director, but there’s also a whole bunch of other people who are involved in this huge project. All those people will have an opinion, and all those people are trying to make the movie - and the score - as good as it can be.

“From the first phone call to actually watching the film - complete with your soundtrack - on the screen can take anything up to two or three years, but usually you’re approached six months to a year before the deadline. You get sent a script, which comes in the form of a book, with lots of added detail and instructions. Stuff like: ‘Scene 1. John is sitting in a coffee shop in London. As the camera pulls back to reveal the city, the music begins to swell’.

“Even though you might have a few ideas, you can’t get too carried away because you haven’t met the director yet. And the director has probably sent the same script to three or four other composers. So, you talk to the director; you talk about the movie and you talk about music. If - and it’s a big if - everything clicks into place, you get hired.”

Then you start making some music?

“Maybe! At this point, the movie might not even be finished, but you can at least start getting a few ideas together and the director might even use some of your music to help edit the film. You’ll also get new instructions: the opening needs to be like this, or this character is no longer in the movie.

“Finally, you get to see a version of the movie, and you watch it 20 or 30 times and you start working on your final score; you talk to the director and other members of the team; they tell you that this works and this doesn’t; this character is now back in, so we need a new bit here…

“Then the studio gets involved. They want it to sound more orchestral or more electronic, so you go through another set of changes and, step by step, you end up with a soundtrack.

“Can you see now why film soundtracks aren’t for everyone? If you’re the kind of person who’s just going to bury your head and say, ‘This is my show. I do what I want’, then you won’t get very far. Maybe that’s why film composers tend to do their best work when they’re in their 40s and 50s - because you’ve got a bit more experience of dealing with the world and dealing with people.

“And you realise that you’re not always right. Other people have brilliant ideas, too, and it’s important to listen to those ideas because they all help you to create the perfect soundtrack.”

Can you see now why film soundtracks aren’t for everyone? If you’re the kind of person who’s just going to bury your head and say, ‘This is my show. I do what I want’, then you won’t get very far.

Before you moved to LA, you were based in Amsterdam. What was the studio setup back then, and how easy was it to shift your whole musical life across five and half thousand miles?

“Ha ha! It was a total nightmare. You see, when I was a kid, I used to work in a music shop. This was at the point where nobody wanted analogue synths any more, because everything was going digital. Guys were always bringing stuff into the shop and letting it go for practically nothing. I’m not kidding - one guy bought in a Korg PS-3300 and sold it for a hundred bucks! What are they worth now? Even if you can find one, you’ll be paying £30,000.

“Anyway, I was the one who was buying up all this old analogue equipment. By the time I did the Elvis remix, I had a massive arsenal of vintage gear all set up in a huge studio. The idea of moving that to the States was terrifying!

“It was obvious that I needed to downgrade, so all I took was my laptop, the Pro Tools and Cubase rigs, a pair of M-Audio monitors, a guitar and a bass. At my first place in LA, the studio was tucked away in a tiny laundry room, but that was all the space I needed. Being in LA wasn’t about having the biggest studio in the world, it was about learning.”

What happened to the Amsterdam studio and all the gear?

“For the first few years, it just sat there doing nothing; gathering dust. In my heart, I wasn’t sure if my film composer plan would work, so I figured that, at some point, I’d be back in Amsterdam.

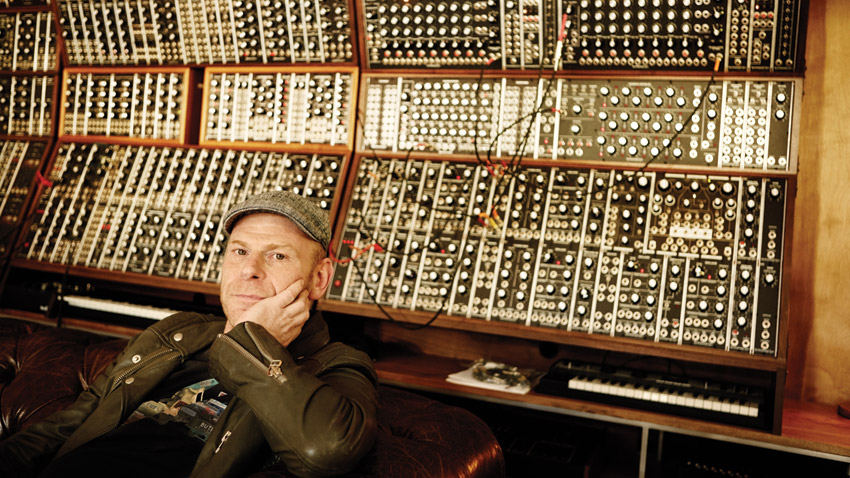

“In the end, it took about ten years for me to really establish myself. One day, I thought, ‘Looks like you’re going to be staying over here. What about the old studio?’. With things like the console and the recording gear, I did a deal with some friends of mine in Holland, but most of the synths and the best of the outboard came over to LA.

“Just recently, I moved into a new place and, finally, all the gear has found a new home. We turned around 3000 square feet into a studio.”

And the vintage gear gets used?

“Absolutely! There was a soundtrack I did last year for a Red Bull documentary called Distance Between Dreams, and that was 100% analogue. I had all this gear running live, with Cubase providing the MIDI information.

“Of course, there were limitations, but that was what made the whole project so much fun. If a synth has only got four voices and they’ve all been used, then you have to find another synth to get what you want. If you’re working with plugins, you say, ‘OK, I’ll have two more versions of this synth’, but hardware forces you to think on your feet and use your imagination. You need to find new ways to solve a problem.

“Please don’t misunderstand me! This is not a complaint about plugins. I love working inside the box and I have been celebrating computer technology for many years. The Atari, Pro 24, the early version of Cubase with only four audio tracks, early VSTs and plugins. I have embraced them since day one and I will continue to embrace them.

“But maybe… just maybe, things have got a little bit too easy in the studio.”

Should making music be harder, more difficult?

“That question is far too big for me to answer. But I’ll remind you of the discussions that took place back in the 80s, when samplers and drum machines were beginning to make their mark. You had a whole bunch of people saying, ‘Hey, these guys are using technology to make music - it’s too easy for them! They’re not real musicians, but they’re getting into the charts. It’s not fair’.

“Things went crazy for a few years, but music overcame those difficulties. The way that great music and great musicians were defined began to change. And the talented people used this new technology in imaginative new ways to carry on making great music. Music that has stood the test of time.

“The era we’re living through today has some similarities to the 80s, but there are also some very important changes. To start with, you have the sheer volume of information that’s out there: music, pictures, software, groundbreaking ideas…

“You also have to factor in artificial intelligence. I have friends who are working in Silicon Valley, and they tell me it’s only a matter of two or three years before we have software that will write the music for you. You will open GarageBand, roll a dice and create a piece of music. If you want to change the beat or the tempo or the vocal line, you will roll the dice again. Then, you call up your friend and say, ‘Hey, I’ve just written a song’.

“There’s no point in trying to fight the march of progress, because you will always lose. For me, I think it’s much better to welcome the future and see change as something positive. Yes, there will be problems and a period of upheaval, but nothing will stop people making fantastic music.”

Tom’s latest soundtrack, for The Dark Tower, is out now in CD format and on Spotify. Stay up to date via his official website.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track