“Why you typically don’t lead a six-piece band with an acoustic guitar is because you can’t be heard! I am shocked that we are able to pull that one off”: Julian Lage on the electric shuffles and engineering miracles behind his most daring album yet

The jazz guitar maestro shares the secrets to guitar phrasing and discusses the irrational melodies and Eno-inspired “sound forward” approach behind his new album, Speak To Me

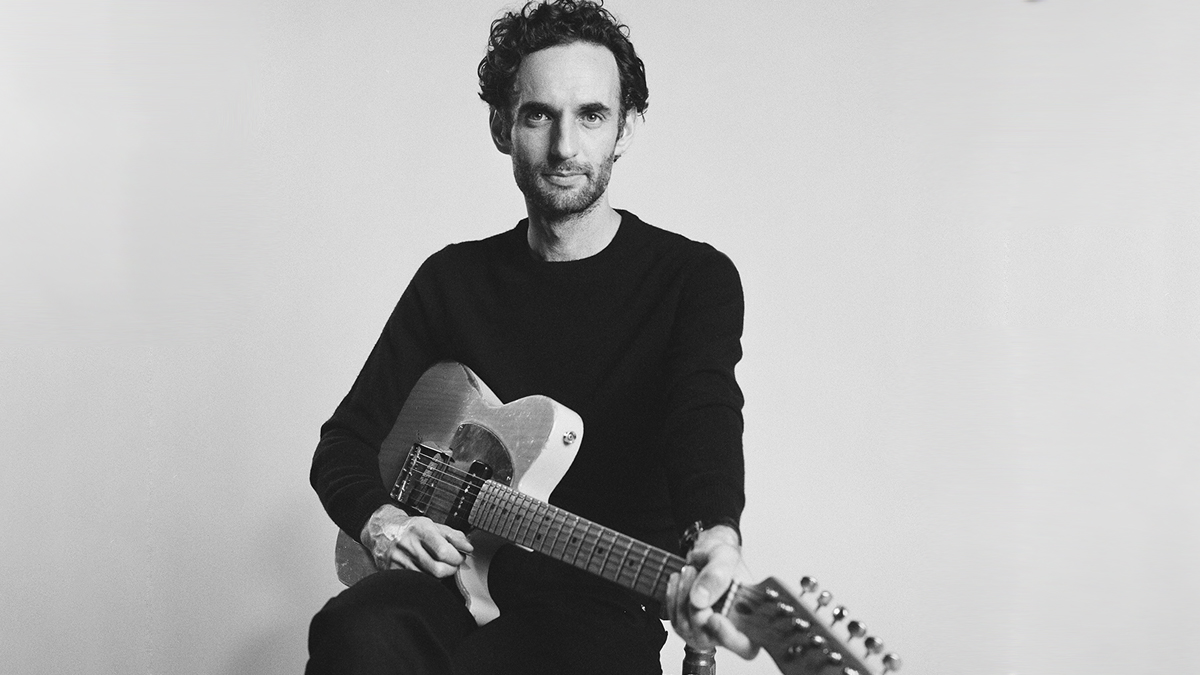

Speak To Me is unmistakably a Julian Lage record. There is the juxtaposition between the considered and the instinctual, the tension between the melodic and atonal. There is that live-wire audacity in his electric guitar, and moments of stillness, intimacies shared via an OM-sized acoustic, all to tell us a story. And yet Speak To Me is quite unlike anything Lage has done before.

His fourth studio album for Blue Note, Speak To Me expands Lage’s usual trio to a sextet, changing the dimensions of the songwriting, finding Lage’s jazz guitar touring through adjacent musical neighbourhoods, drawing from gospel, hymnals, acoustic folk, the blues, with the acoustic sharing more of the burden than we are used to hearing, his 1657 Nachocaster T-type with the Ellisonic P-90 at the neck shouldering most of the electric work.

But for a recording that stretches the dynamics between raw electric and pure acoustic there more occasions for Lage's guitar to recede into the background, to sketch out the track and let the other instrumentation colour it in.

Lage credits producer Joe Henry for being able to pluck his often improvisational ideas out of the air and make them happen.

“I think with Joe Henry as producer, he was able to steward songs of mine that I think often do get left behind because they’re a bit enigmatic,” says Lage. “You have these songs like Hymnal, South Mountain and Vanishing Points, these are three songs on the record that are very gestural, and frankly aren’t guitar features either. The guitar has a voice, a certain character, but the majority is the orchestra playing.”

The Speak To Me ensemble brings together some formidable talents. Lage drafted the “powerhouse” Canadian pianist Kris Davis, with Patrick Warren joining her on keys. Levon Henry is on wind instruments, while the virtuoso Julian Lage Trio rhythm section we all know and love is in full effect with Jorge Roeder on bass and Dave King on drums.

The six-piece band presented new opportunities. New challenges, too. This might be a very different record but the same creative obsessions that drove his Blue Note debut, Squint, allied to a sense of storytelling that gives Lage this novelistic depth to composition remain animating principles here. Only this time it didn’t always have to be all about the guitar and how and what he was playing.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Joey Baron [Bill Frisell/John Zorn], the drummer, and one of my heroes, we were working together a while back and he was talking about the importance of not just playing the guitar but playing music,” says Lage. “He said that it was vital that you use your resources to tell a story and not feel like the point is that you can play, because hopefully by a certain point that’s established.”

Lage sees Speak To Me as “a record of spirituals, a form of gospel,” and at times a melancholy work.

“I like to think of it as a more three-dimensional emotional landscape than I have ever tackled on a record,” he says. When there are all these emotions floating around, then mood can shape the narrative and take it where it needs to go.”

Of course there is always a directive or narrative at play but I do not feel like it has to be my narrative

Jazz can be abstract when it needs to be, trafficking in moods and colours, and so it is here, where Speak To Me can take us from the papery textures and unfinished thoughts of Hymnal, right into the skronky über-groove of Northern Shuffle and its thrill-ride lead motif that has the character of Link Wray through the wormhole, and then on into the pastoral acoustic melodies of Omission.

“Joe’s mastery as a producer is that he can sow things together,” says Lage. “I can say, ‘I think they are connected because I wrote them, but surely when I go to record I have to focus it.’ And he will say, ‘No, no, no. Just put them next to each other and the ear will do the work for you.’ I’d say those were some of the key signifiers that make this body of music different to something else I have done before.”

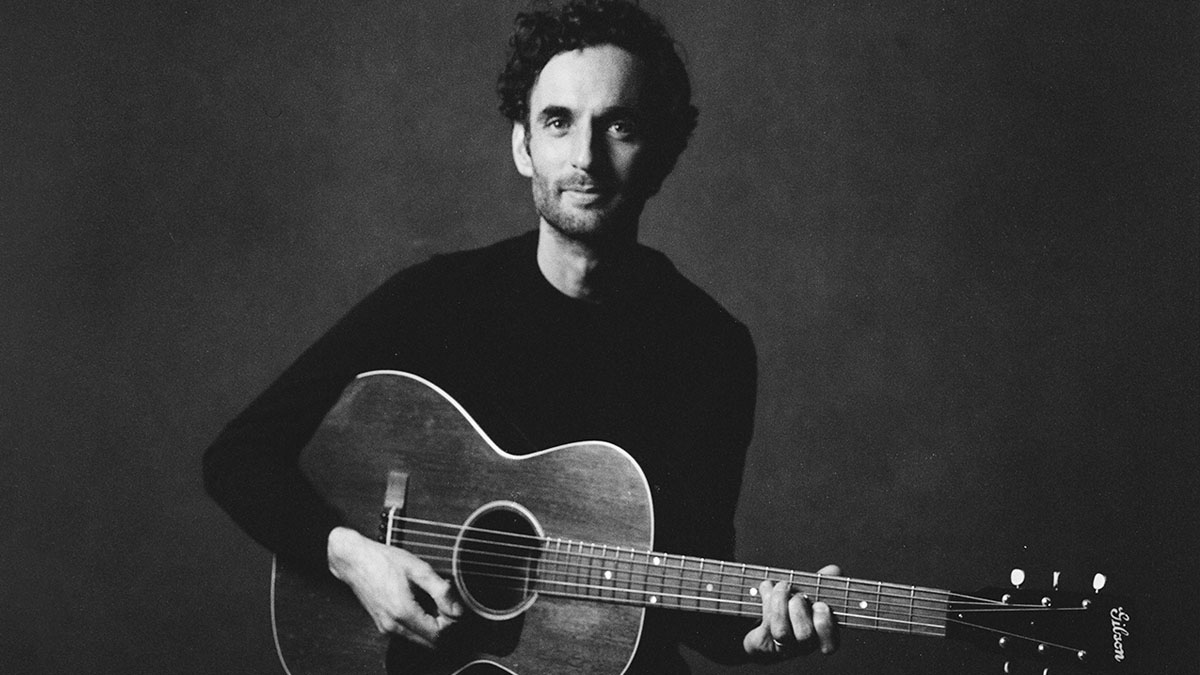

As to the story? That’s the audience’s call. But it is hard to resist the impression that this is some kind of journey, and we’re experiencing the agonies and ecstasies that come with it. There is a melancholy, but there’s also a playfulness, often within the same arrangement, as on Me Around You, which is six minutes of world-building with acoustic guitar, fireworks and watercolours on a Collings OM.

Ultimately, we terminate at Nothing Happens Here, and wouldn’t it be nice to be somewhere where nothing happens, just to escape for a little while?

“The dream is that you present music that has room, and a spirit of generosity, so the listener can have whatever relationship that is genuine to them,” says Lage. “That is as much the story as anything. I think just generosity of spirit. ‘Here’s all the resources. Here’s the material.’ And of course there is always a directive or narrative at play but I do not feel like it has to be my narrative.”

With track like Omission, in another dimension, another timeline, could this have had vocals?

“It could be on a vocal record, right? It’s funny you say that. We just, two nights ago, in San Francisco, performed with this band for the one and only time. We made the record in the studio, and we did Speak To Me live a couple of nights ago, and Joe Henry performed with us in the middle of the set

“He came on for two songs in the middle of the set. And to your point, he is such a storyteller as a singer, I think I was just struck by the instrumental music and his singing, lyrical music were one and the same and I don’t understand why. Frankly, I’m kind of perplexed. But I was thrilled by it.”

Speak To Me has a different focus for the guitar. There is less pressure on it – it has to carry less. With the other instrumentation, there’s room to not play. How did that develop?

“You’re so right. I was listening to a lot of Brian Eno at the time. I was really trying to figure out how you could present a record of sound that happened to have music and songs in it – but it had to be sound-forward. Our engineer, Mark Goodell, is a huge part of that.

Logistically, why you don’t lead a six-piece band with an acoustic guitar typically is because you can’t be heard! I am shocked that we are able to pull that one off

“I mean, to me, he is almost like a co-producer because one really distinct, singular part of this record is that it is centred around the acoustic guitar, which inherently is way quieter than everyone else on the record, and, logistically, why you typically don’t lead a six-piece band with an acoustic guitar is because you can’t be heard! I am shocked that we are able to pull that one off.

“It set a parameter where vulnerable acoustic music could lead the charge and, by the same token, be invisible and blend into the background, and I think you hear that on something like 76, where you have this guitar that’s really attempting to lead the charge and just as easily could be overtaken by Kris Davis, who is just a powerhouse, and completely decimates everything in sight with her brilliance. I just want to acknowledge that the sonic side of it is akin to production. And obviously, [acknowledge] the players.”

There is something about that in the recording, turn it up loud enough and there is this sensation of curved air, and that is something that we certainly feel in our guts when we see you live, especially when Jorge’s bass comes in. It’s like it takes blood away from the brain and toward the gut.

“Yeah, I think you’re right. You’re right! [Laughs] I think you’re spot on. This is stuff is so sensual. It really is so sensual and I think records are just fascinating; they’re fascinating in the sense that you can direct sensuality, or you can invite someone to experience something in a different way.

I think records are just fascinating; they’re fascinating in the sense that you can direct sensuality, or you can invite someone to experience something in a different way

“Even making it, I’ve never felt that way in a studio. I didn’t know you could be surrounded by so much sound and also have such a stillness, and a quiet to it.

“That’s a testimony to Patrick Warren and his sensibilities, and Kris Davis and hers, and Levon’s, Dave and Jorge. These are incredibly centred and giving people, and I think you can hear that radiate through every track – and I am very lucky that I got to be there frankly!”

The fact that Northern Shuffle is the longest track on the album is not surprising. What’s surprising is you found a groove like that and could quit it. Tell us about this groove, and how much fun that is to play.

“Over the course of preparing for the record, which we did mostly in Europe, on the European tour with just the trio, I would write and we would play at the soundcheck, then I would go home from the gig, rewrite the tunes. I think we had a body of 30, 35 in that range, and I don’t think at that time how it was going to become a bigger orchestra. But I knew it would.

“We practised as a trio. At Union Chapel [in London] we were working on some of the tunes that didn’t make it on the record, just because I didn’t get them done in time. One of the through lines I kept coming up with was, ‘Let’s find a groove.’ Obviously I have this fascination with the history of guitar but also with the history of bass playing, and the history of drumming, and one of the things I think we are all obsessed with is the shuffle, the history of the shuffle and African-American music.”

“And shuffles sound different played by different people. I think the shuffles I am most obsessed with are what you hear with T-Bone Walker and Muddy Waters, and Howlin’ Wolf. We’re talking history of the drums but the shuffle is a big part of the history of guitar. Dun-dah-dun-dah / dun-dah-dun… Whatever that is, and it is different for everybody – it is no way shape or form meant as trying to replicate [something] but finding your own personal shuffle because people feel that very idiosyncratically.

“Northern Shuffle, that particular tune, I wish you could hear the original because it is really a solo guitar piece, and it is a study. There are kind of two songs happening at once. There’s the shuffle and then, in a way, this irrational melody that has its own tempo. It’s almost a Paul Motian melody. That’s how I thought of it.”

What is so interesting about phrasing – and it’s the same for speech – is dramatic pauses, accentuation, change in pitch of the voice, change of speed, where you feel like you are rushing towards something and then all of a sudden you pull back

“It's a little bit of rubbing your stomach and patting your head, where you go between the shuffle and the free melody shuffle, and then at the V chord they converge for the grand finale. Yeah, I’d say that tune represents the rhythmic and kind of physical heartbeat of the record, and developed from this three-way fascination. Then you bring in the full band and it just sort of erupts.

The tone on it is so gnarly and wiry.

“Also it’s the song where I am using a guitar from the studio. It wasn’t my guitar. It was an old Epiphone electric, tuned to down to C, standard tuning in C, so I am playing it in E to accommodate it but I am almost lost this whole time because I am trying to figure out this guitar – an Epiphone Coronet, courtesy of Andy Taub, whose studio it was. But anyway, that song, there is a lot going on, at least for me!”

There’s something really unworked and raw but cerebral too about Northern Shuffle. It’s like Michelin-starred food in a roadside diner. How much distance is there between a rock ’n’ roll and a jazz phrase?

“Oh my God, let’s just take a moment and acknowledge how spot on you are. I am a student. I am a student of this music. I love it, and I am so humbled by it, and when I say ‘music’ I mean just music. And when you are dealing with the relationship between rock ’n’ roll phrases and blues phrases, or what we consider folkloric phrases, or jazz phrases, bebop phrases or the phrasing of a modern improvisor, absolutely there’s crossover.

“I mean, it’s that classic thing that a phrase doesn’t really start till you stop. That’s when the reflection begins and you go, ‘Oh my God, I just head a phrase.’ And so I do think of phrasing as something that is about punctuation, which is not novel, and I think it is what a lot of people teach.”

And phrasing can be as individual to a player as the shuffle is.

“Because I am not terribly capable when it comes to effects – I don’t know how to use pedals really! [Laughs] I don’t have that ability to think about sound the way so many of my friends can, where you can develop this real deliberate, guitaristic thing, with delays, reverbs, all these things, and so I feel like I am dealing with duration of notes, whether it is loud or soft, high or low. Those are the dimension most people are dealing with – any acoustic instrumentalist, right?

“One of the things that kind of gets in the way of phrasing is run-on sentences, sometimes, and it is not to say you can’t play long phrases but it is a classic thing, at least for me as a guitar player, to think so legato, that you’ve got so much smoothness that the ear doesn’t get interrupted.

“What is so interesting about phrasing – and it’s the same for speech – is dramatic pauses, accentuation, change in pitch of the voice, change of speed, where you feel like you are rushing towards something and then all of a sudden you pull back.”

There are already so many variables with what you can do with your phrasing on the instrument before you even think about the tones and the other dynamics you want to use.

“Also, incongruence, when you are playing a completely different tempo from the other person, or speaking faster than the person you are speaking with. Those are the things that fascinate me. Okay, now you connect that to the history of rock ’n’ roll and jazz, and I think they are hallmarks of our favourite players. There are infinite ways to do it. Context is everything.

“I don’t think phrases exist out of context. Between the bass and the cymbals on the drums, you already have this full spectrum of sound, which I think as a third player in that dialogue. I have the opportunity to point that attention more towards the bass, more towards the drums, more towards what’s not being made [in sound], and I say with complete humility that it is an obsession of mine to learn how that works, and I keep learning about it all the time. All the time.”

Sometimes the lessons or inspirations for the phrasing don’t come from music. They’ll come from literature, or prose, and how punctuation in words can be used on guitar. And those long phrases are hard work, physically, and high-risk musically, but they can make the audience hold their breath.

“My God, yes, it’s physical, and you’re right, it does come from other sources. I mean, I think it is even in speaking to you about the record. I am still learning about it. I wrote music. I played, and I loved every second of it, but I can’t pretend to understand the life that any project has of its own, and in sharing the music with others I look at it and go, ‘Wow! Now that you say it?’

“I didn’t think of it that way but that is exactly what’s going on. I think just the lesson that keeps coming to mind is that there’s room for everything, and you hear that musically. You hear that emotionally on the record.”

It is the most orchestral record... but I didn’t write anything but the melody and the chords. I wrote a tune and then these players know what to do and their contributions are my favourite parts

“There was an interesting moment, I think it was the second day, when Kris Davis came in, but I had a song, South Mountain, or maybe it was Omission, regardless, I got really nervous. The conversation was as follows: ‘You know what? I prepared as much as I thought I could but this song, I couldn’t come up with marching orders for the band. I am kind of hitting a wall. I’m so sorry.’

“And, of course, [Joe Henry] being the experienced master that he is like, ‘Thank God you didn’t have anything prepared. I would like to treat it differently.’ I said, ‘Okay, what did you have in mind?’ I’m paraphrasing but he basically said, ‘How about we get in a circle, the whole band, and you sit down and you play us your song, and we’ll honour it, we’ll consider it, and we’ll do our best.’ I was so moved by that.”

That’s what the BeeGees used to do.

“Exactly! It’s true. It is. Just be together with it. We’ll honour the space. And I don’t think I had ever considered throttling back from this, ‘I gotta be ready! I gotta do this!’ What a kind and gentle way to hold a space for me, and also what a kind and gentle way to invite the others to be themselves.

“The great irony and beauty of this to me is that, in many respects, it is the most orchestral record. I’ve attempted things like this before but I didn’t write anything but the melody and the chords. I wrote a tune and then these players know what to do and their contributions are my favourite parts.”

One thing about Jeff Beck was he was always himself, and he left space for others

Maybe it's a case of, the better the guitar player you are, the better you understand that you want to hear the other musicians play as well.

“The other people! I feel like that’s Jeff Beck’s thing. One thing about Jeff Beck was he was always himself, and he left space for others. I say that, not that I am even getting close to that, but it is one of the things I was thinking about Jeff a lot since he passed, and I never met him and I’m a big fan. I continue to learn that specific thing from him.”

What microphone did you use for the acoustics, particularly on Me Around You? Because the tone sounds so sweet. The whole track plays like a meet cute.

“Yeah, yeah, right! Ha! I’ll be hard pressed to remember exactly but it was an old RCA ribbon mic with a [Sony] C-37, I think. I made a record years ago called World’s Fair, and it was all acoustic guitar, and I was obsessed with the C-37. That was the main sound, and I think a Neumann. It is a couple of mics here and then maybe one further back. But I think it’s an old ribbon, and I think an old Sony, but it does sound awful good.”

Shin-ei made a pedal that highlights just about everything on an electric guitar that I love. It’s high-end but it’s not the brittle stuff, and it glues to the midrange

There are some tones that have got a bit more gain and grit on them. Going back to Northern Shuffle, what is pushing the amp there? Is that your Shin-ei B1G 1 boost?

“Well that’s always on. I never turn that off. It’s always on and I’m proud of it – not proud because I did anything but I am proud of them because they made a pedal that highlights just about everything on an electric guitar that I love. It’s high-end but it’s not the brittle stuff, and it glues to the midrange.

“Often with Fender amps especially you can have this scoop in the middle, where you have this beautiful low, and kinda scooped mids, and then this bright high. This, I wouldn’t say it fills this gap but it connects the high-end to the scoop. It bridges the high-end to the scoop. I’ve had pedals that fill the high-end. I used to use a JHS Morning Glory, and that kinda just filled the bowl, and I love it for that reason, but this one just universally works.”

“There were two ways we got gain on the record, and I couldn’t tell you when one which one happens. The dominant one is two amps at once, so probably what you are hearing are the Magic Amplifiers Vibro Deluxe – and that’s basically a black panel Deluxe – running with a ’59 tweed Champ at the same time, right next to each other.

Depending on how much grit we wanted, Mark Goodell just turned up the Champ. But there’s also – maybe on Speak To Me – a Pete Cornish compressor, and that’s always on, barely on... Depending on how much grit we wanted, Mark Goodell just turned up the Champ

“And so the Champ is turned up louder and it’s getting gritty, and the Deluxe is just a bigger, clearer signal. That was one way. Depending on how much grit we wanted, Mark Goodell just turned up the Champ. But there’s also – maybe on Speak To Me – a Pete Cornish compressor, and that’s always on, barely on, just barely, barely on, before everything. It just makes that impact a bit softer, but it’s almost impossible to tell the difference to when it’s on or off but I can feel it and I like it.

“My wife, Margaret [Glaspy], has a Cornish overdrive/compressor pedal and I think for Speak To Me I borrowed the pedal but just used the overdrive, and then that is probably going into the two amps driven. But the bias is just towards the Champ and the Deluxe simultaneously.”

Those two amps sound so nice together.

“They are both beautiful. Pete Cornish, I mean have never had the privilege and pleasure of meeting him. I think he is maybe an hour-and-a-half or so out of Brighton. He is in the UK. But he is the original master, the inventor of the pedalboard guy.

“The EQ profiles on his overdrives and compressors are so favourable to a guitar. They sound like old amps. But there is nothing like turning two amps up loud and seeing what happens.”

This record has got everything. There's a wide sweep of sounds. You’ve got that Marlon Brando in The Wild Ones vibe with the gain, and then the Joni Mitchell folkish sounds, like on South Mountain, where we’ve got this guitar sound that’s homely and familiar, and then avant-garde noise.

“You’re so right! That guitar was one of Joe’s. That’s an old Gibson. I have one, too, that I brought out for the session. I want to say his was a ’30 or ’31 Gibson LG-0. There was a rare batch and they were all mahogany, and 13-frets to the body, and that’s what I am playing on those songs. He’s got a beautiful one, and that’s the guitar down a whole step.”

And going back to the larger ensemble, maybe that range is because there is more instrumentation there to offer sounds for your guitar to explore.

“When I listen to Speak To Me, I think a big part of it is Joe, and Kris Davis, Levon Henry and Dave and Jorge. It’s that sense of a big orchestra. I think what I love about it is that I am allowed to rest. I made this record during a pointedly difficult time.

“All times are difficult and all times are wonderful; that’s kind of the way of human nature. But I can’t stress how much I needed this band to allow me to be where I was with the music. You’re seeing a vulnerability and not only is nothing lost [when I don't play] but a lot is gained because of that, and for the ensemble I am very grateful.”

- Speak To Me is out now via Blue Note.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.