Jordan Rakei: “For this album, I tried to finish writing a song a day”

The singer-songwriter-producer on his gear and creative process

Having spent his formative years programming beats in his Brisbane bedroom - resulting in two early EPs - Jordan Rakei’s decampment to London in 2015 launched a flurry of creativity. He lent his distinctive vocals to Disclosure for their album, Caracal, then released his own debut album, Cloak; both showcase his soulful tones and precocious talents as a songwriter.

Things went to another level when Rakei signed to ever-innovative label Ninja Tune, before releasing second long-player, Wallflower to copious plaudits in 2017.

Over and above the eponymous releases, Jordan Rakei has also functioned as one quarter of the Are We Live crew (aided and abetted by Tom Misch, Alfa Mist and Barney Artist) whilst DJing and releasing more dance-centric tracks under his Dan Kye alias. Meanwhile, Rakei has been championed by luminaries such as Simon Green (aka Bonobo), Nile Rodgers and LA behemoth producer, Terrace Martin.

Jordan’s newest offering, Origin, is a stunning set of well-crafted, soulful songs that see the 26-year-old exercising the freedom of having his own designated recording space, while the singles, Say Something and Mind’s Eye, show Rakei at the top of his musical game.

We ventured to South London to catch up with Jordan and to find out more about the synths and circuitry that let the soul flow.

Is having your own studio setup essential to you as a songwriter/producer?

“It’s been huge as it’s the first time I’ve had my own setup since I moved to London. Back in Australia, I lived with my mum and I had all my gear in my room, but I’ve lived in London for four and a half years without having any proper place to work. I was mainly just working on a laptop with headphones and having to hire studios. Having the workspace for this new album, I basically tried to set myself a nine-to-five work routine, and to try and finish writing a song a day. Finally having a studio with all my gear here was amazing.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You sound very disciplined about your writing process. Is that part of your secret?

“Definitely. I’ve been asked a lot in interviews about writer’s block and I’ve been referred to as a prolific songwriter, but I don’t necessarily think I am prolific, I just do it more. I assign myself more time to do it and I force myself to come out of a day with at least something I can work on. I think that the time you have to put in is actually the toughest bit.”

Do you suffer from the modern day problem of too many options or are you well disciplined?

“Sometimes, but with this album, I was writing everything on piano and I wanted to have around 25-30 songs that were pure piano songs. Then I would choose my favourites, maybe 18 songs, out of those, and do some pre-production on them before choosing my favourites to finish and record.

“So, I kind of knew as I was working on them which were the strongest songs and which way I was wanting the album to go, so I was cutting songs as I went along. So, yes, I guess I had to be disciplined cutting back.”

Does the tech help you write or do you write and then add the technology later?

“In the past I would maybe make a beat then write some lyrics around it; I’ve always had different processes. With Origin, I specifically wanted it to sound like traditional songwriters and arrangers like, say, Stevie Wonder, with a proper pre-chorus and a bridge.

“To do that I had to sit at the piano and come up with interesting chord changes, which I’d then mess around with to make them sound fresher and more modern. It was really challenging as I’d never done it like that, producing after I’d written the songs.

“So, it was just trying to have the vision as I went along that something might be a piano at the moment, but it might become a Prophet or a Juno part. I needed to keep that in mind the whole time.”

So being both the artist and the producer can be useful?

“It’s so helpful. The problem was that I was letting people hear my demos and they couldn’t hear what I had in my head! I had to tell them to trust me as things like fake strings would be real strings. I just had to trust it from the beginning and, finally, when we started mixing the album, everything started falling into place.”

What are the essential pieces of kit in your studio arsenal?

“So, the big things for me are an upright piano and a Fender Rhodes, which were my main songwriting points for Origin.

“It’s more like a nice little solid writing room so I’ve got an original Juno-60 and a Prophet Rev 2... the 16-voice one, which is amazing. I’ve got a vocal chain that’s always set up in case I get any ideas; basically what I’d do as I was writing the songs is to sit on the chair with a U87 mic that goes into a Neve preamp clone made by BAE, which is amazing.

“So, all the vocals were done with me sitting down clutching my mic stand!”

Is it a pain recording your own vocals?

“No. I’ve got a really fast vocal recording workflow. I’ll sit there, press record, create a new track, record the backing vocals. Because I stack lots of vocals, it’s better that way than standing up and going back and forth to record. I just turn my head and sing! I share the studio with a friend of mine called Alfa Mist and he’s got his drum kit in a separate room so we can record some drum and percussion stuff. He’s also got a Yamaha Montage keyboard, which is amazing. I’ve got a little bit of outboard gear too, but nothing crazy.”

Have you any particular favourites amongst your outboard?

“I have the Warm Audio EQP-WA tube equaliser, which is the Pultec clone. I use that on my voice. When my drummer, Jim, and I were mixing Wallflower we always found that when we were mixing my vocals, every single track we’d be scooping a section around 200/250Hz where it sounded really muddy. So, I just committed to destructively recording with the Pultec clone active and scooping out a little bit in that range. In mixing, we found that sounded fine and not too thin. Doing stuff like that saved us a lot of time in the long run.”

What DAW are you running everything into?

“I go into Logic. So, I record the vocal into the BAE Neve preamp clone, into the Pultec clone, through my UAD interface and into Logic. I’ve been using Logic for around four years.

“I started making music on Fruity Loops when I was 11, then moved on to Cubase, which I was using right up until my first album. I’d developed all my keyboard tricks and shortcuts with Cubase so I had to start from scratch again when I switched to Logic.

“My workflow is really key to my music-making, I like to get things done quickly and I remember when I first moved to London, spending two days just researching every shortcut and, like, practising editing so I was basically practicing my shortcut chops! Watching my drummer, Jim, who’s really quick on Logic, helped too, and now I couldn’t see myself leaving Logic, purely because my workflow has become so quick.

“I know Ableton is super-quick, but I’d have to learn all its shortcuts again and I’m not really willing to do that.”

With the complexity of modern DAWs it certainly is a daunting prospect to leave a familiar one behind to learn a new one, isn’t it?

“It was mainly because everyone was using Logic when I moved to London and that’s why I made the switch. Like I said, I’d been making music in my bedroom for about ten years and I’d never collaborated with anyone so had never felt like I had to learn any other platform. I was still using Cubase V3 right up until 2015 [laughs]... then I learned that there’s more in the world!”

Do you wish you had an engineer working with you to handle drop-ins and technical issues?

“Weirdly, because I’ve got my own flow, when other people do it, I’ve found that I’m not great at articulating what I need them to do and that actually stunts the process. Like, when I do that gang vocal thing, I’ll do four of the same with each note and I do three harmonies so there’s, like, 12 tracks. I always level them similarly so in every song I know my high harmonies will be sitting at a certain level. So, when I’m doing it myself I just know my little way of doing it.

“That was one of the massive things about getting my own recording space, being able to do my own vocal recording like I used to back home in Brisbane. I tend to lay down the vocals really quickly and if I do a bad take I just delete it rather than sit there and comp it all up.”

Is comping the thief of studio time?

“You’ve done four lines of the chorus really great, but the last line. I find that if I do it all again then I can get it whereas if I try and just punch in on a line, I can never get it that way. So, I try to do full takes.”

Sounds like you’ve evolved a template that’s helping you streamline your studio workflow...

“Yeah but what’s weird now is that I’ve done all three of my albums slightly differently. I want to challenge myself in some new way: I don’t want to change DAW, but just want to try a different way of doing things for the next album. Maybe not the vocals, but maybe just the rest of the process differently. I don’t really know how yet, but it’s something I’m thinking about as I’m preparing for the next album.”

Is it hard to achieve a good balance between soulfulness and synthesizers?

“It really is [laughs]. There’s always the urge to add technology. If I’m writing a song on my Rhodes and it sounds good - which the Rhodes always does - I’ll be thinking, ‘But loads of my songs have Rhodes in them’, so I’ll be trying to force in a new instrument. So, I’ll maybe try to create a similar sound on the Juno, but then some friends who make dance music said to me that Junos are on everything, so I move to the Prophet... [laughs]. I’m constantly trying to make different sounds!

If there’s a Rhodes part that works then I’ll just keep it and try not to overthink everything.

“I did do this process where I didn’t want to be too judgmental as I wanted the album to sound quite fun. So, if there’s a Rhodes part that works then I’ll just keep it and try not to overthink everything. That said, I did use the Juno quite a lot on Origins, too. Someone sold me the Juno about a year ago and they were like, ‘I’m probably gonna regret this and email you in a year asking if I can buy it back’, but I said, ‘Sorry, no’, [laughs] as they’re so hard to get and it’s in great condition, too. The Juno has a lot less functionality than, say, the Prophet, but you’re paying for that warm, chorused sound with the Juno.”

You’ve mentioned your hardware chain for your vocals going in to Logic. Once they’re in there do you use much software on them?

“We use a bit of compression on them as sometimes I sing really low and really dynamic, so we compress heavily on one chain then just level it on the next chain, basically.

“I grew up listening to lots of dub reggae, so I find you can merge sections really easily by throwing the last line through a dub delay. Generally, I’ll track a vocal and set up a dub delay buss as that’s always a nice touch to blend sections. I never have anything too crazy, though. On this new album I have a few songs where I have double-tracked vocals and try to make it sound a bit retro with weird slapback delays and stuff.”

A lot of the lyrical content on Origins explores the creep of technology into our lives; do you have a love/hate relationship with technology?

“It sort of is. I’m coming at a lot of the songs from the point of view of me putting myself in that fictional future where it’s not all great, and asking what we can do to stand up for ourselves when there’s AI running our governments. I guess it’s a projection of where I think things could go, but I think part of me tries to embrace the inevitability of technology yet there’s also a part of me worried that we’re going to lose a lot of the humanity inside us.”

Could you talk us through how you assemble a track like the beautiful Oasis?

“The main sound in Oasis is the Juno-60. I got in the studio with my friend and we were writing the keys and the guitars with the same melody. It’s basically a song about a character who has relocated to a new planet where he’s alone because he’s trying to create a new civilization for humans. I didn’t want it to have a typical arrangement and I wanted it to get really chaotic at the end with the drums representing his mind going into a frenzy before coming back into the groove.

“I worked with Richard Spaven on the track, who is an amazing drummer. I built up the instrumental track and then sent him a beat-boxed version of what I wanted the drums to sound like! He couldn’t believe he’d just received demo drums from a beatbox. What you hear on the track was basically his second take... he just killed it!

“I had an idea in my head of marching drums, but a bit more hip-hop style and he totally got it. That’s one of my favourite tunes on the album.”

To quantise or not to quantise?

“Sometimes it’s hard because I always record one thing at a time. I have done songs in the past where there were four of us recording with a drummer and I haven’t quantised. If the drummer sways then so will the chords.

“There are some songs on the album where I did have to lock in, because I’d recorded the bass and the keyboard to a grid. So, sometimes the drums, or a guitar part that I’d played in had to be quantised so I could get them to sit in.

“I’m not a big quantiser but if I need a synth line to be exactly like I imagined it in my head, then I’ll use it. It’s a handy tool to have sometimes, and that’s why I feel lucky [laughs]. I can’t imagine what Earth, Wind and Fire must’ve done back in the day!”

You’re attracting the attention of important players like Nile Rodgers. What tech did you take along with you when he invited you to Abbey Road for a writing session?

Getting to work with Nile Rodgers at Abbey Road was amazing. He's really charismatic with so many great stories; a really funny guy.

“I just took myself. Getting to do it at Abbey Road was amazing. Nile’s really charismatic with so many great stories; a really funny guy.

“It was wonderful learning from him and I actually played him some new songs from the album and the song Rolling Into One, which is built around a bassline with one chord for the whole song - that got him excited. He was like, ‘We’ve got to make a one-chord song just like this,’ so he started playing a riff and his engineer, who was one of those Americans with insane skills that doesn’t even need a mouse for Pro Tools, he was just boom-boom-boom with all these shortcuts.

“It was quite surreal to be asked to do it, but when you get there it becomes real and, when I left, I felt proud that I could hold my own in a session like that.”

Presumably the same applied when Kendrick Lamar’s producer, Terrace Martin approached you to do a session with him in Los Angeles?

“Exactly. He’s another one I learned from. In that LA songwriting world, he had like ten people in the studio; it’s such a different way of working. One guy who makes beats for Dr Dre and others was on headphones making the drums on his laptop. He played the beat and Terrace said it was cool so they did like a stereo out from his laptop with an Aux cable and tracked it in.

“Obviously, he trusts the programmer as he can’t then mix the drums as it’s just a stereo file. That way of putting things together was different but made me think: I could get the drum production ‘guru’, a cool guitarist, then I could do producing in the sense of directing, rather than actually playing. That way of producing - where people are directing the session as opposed to playing every part - is really interesting.”

Exposure to those different techniques can really open your eyes to new processes, can’t it?

“Absolutely, and I think I would really enjoy working that way with my own stuff. A couple of songs on the new album, I wanted the basslines to be really crazy, so I got a guy in to play it and similarly, with a keys part, I wanted to be really musical. So, I was directing them, but not actually doing anything, and it was fun because the songs came to life way more than I would ever have been able to. It did make me wonder if that’s what all the big artists with the huge budgets do - just get the best players to come in and lift the music to another level?”

What do you lay your own beats down with?

“I probably do my beats in a more unconventional way than other people do, I think. I basically get lots of sounds I like, then drag and drop them onto my DAW. I don’t play them in with a MIDI keyboard or anything, I just visualise the drum pattern in Logic then I mass copy and paste it over the session. It’s pretty simple, really. For me, it’s making a song with produced beats then just playing bass or keyboards over the top of it, and that’s pretty much how I started making music; beatmaking on Fruity Loops and learning how to arrange.”

Are you all in the box now?

“My studio is only in the box. When Jim, my drummer, mixed it with me at his studio, he was sending some of the tracks out of the box to his Trident-series desk. Plugins these days are amazing, though, and we managed to create most of the things we needed with the UAD stuff.”

Any new kit you’d like for the next album?

“I had a wishlist of things to buy for myself, which I wrote as I finished recording the new album. I’m sure everyone wants one, but I really want to get a good condition Neumann U47. That’s something I’m saving for! On Origins, I recorded the backing vocals with the same mic as the lead vocals and sometimes it sounded like it was almost phasing and someone suggested to me that if I did my lead vocals on one mic chain, then did the backing vocals with a different mic, it would add a nice character. [laughs]. So, I’m thinking the most expensive backing-vocal mic in the world could be a U47.”

I’m the Deputy Editor of MusicRadar, having worked on the site since its launch in 2007. I previously spent eight years working on our sister magazine, Computer Music. I’ve been playing the piano, gigging in bands and failing to finish tracks at home for more than 30 years, 24 of which I’ve also spent writing about music and the ever-changing technology used to make it.

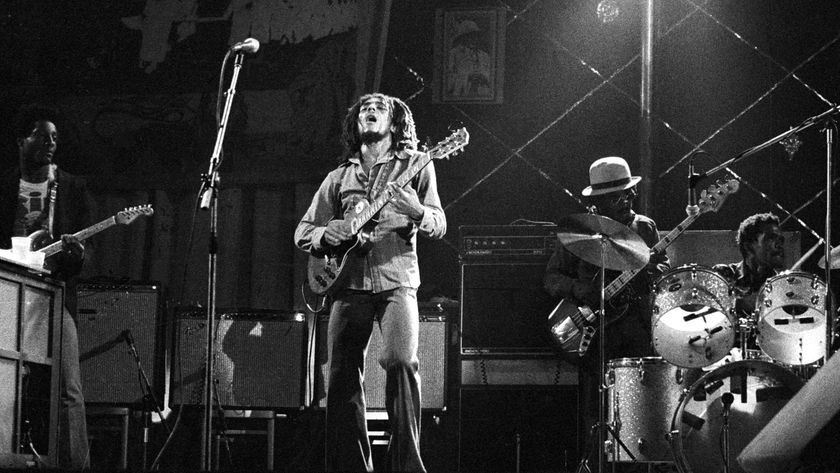

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues