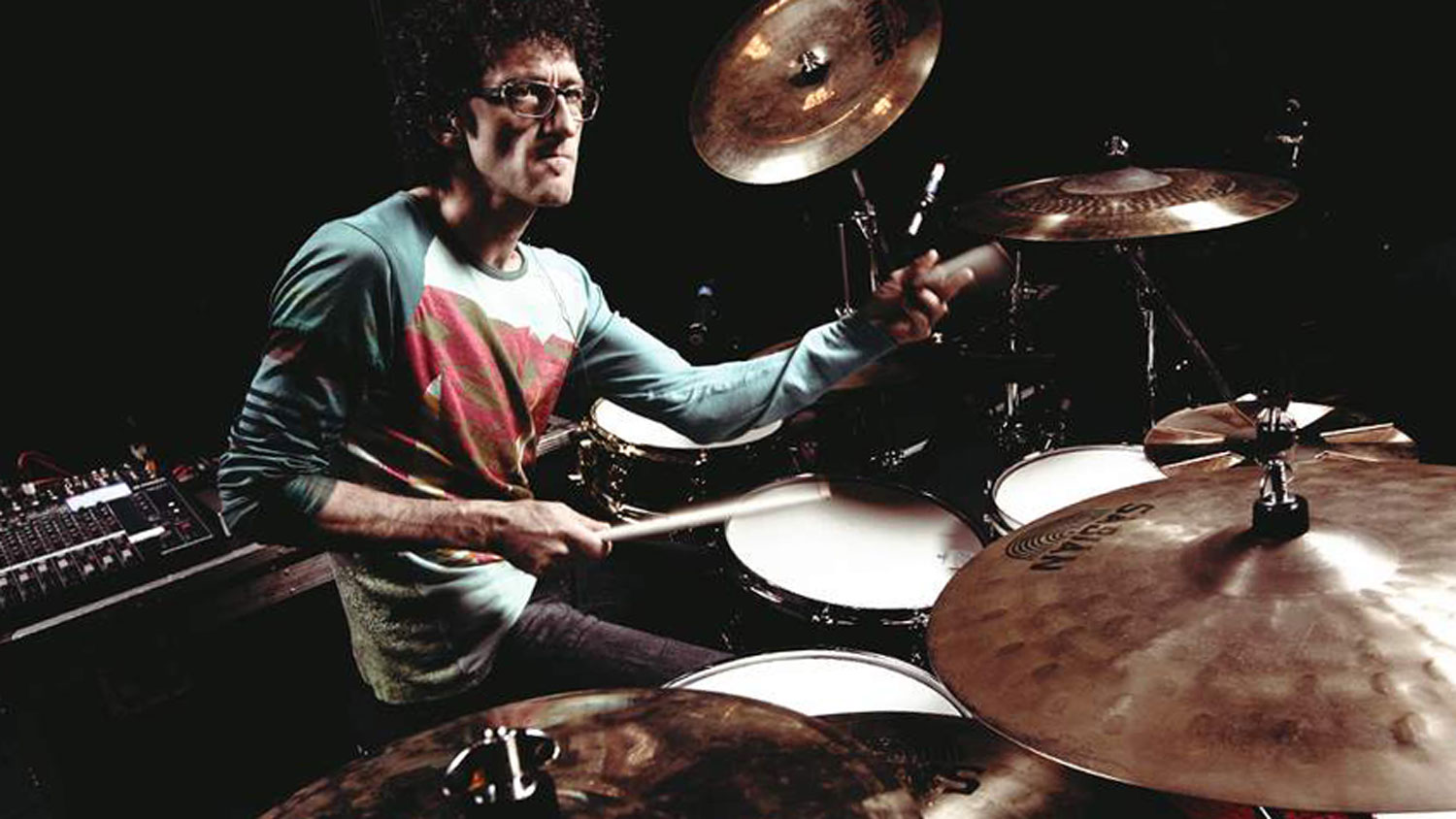

JoJo Mayer: “The music industry is already dead. Something new is going to happen”

The ground-breaking drumming pioneer taking audiences to places they’ve never been before

Born in Switzerland and based in New York, Mayer formed live electronica trio Nerve when he didn’t find the progressive spirit that he was looking for in New York’s jazz scene.

Instead, he drew influence from across the Atlantic. “I was looking for freshness,” he says. “I heard that freshness with music that was predominantly produced in this country – Massive Attack, Aphex Twin, the Chemical Brothers, all the old-school jungle stuff.

Music is a communal experience, always. That’s one of its powers.

"It was my dream to put together a band and make that. I started to organise party events where I invited people to jam, so eventually this group emerged.”

Mayer’s ground-breaking approach took the syntax and sounds of electronic dance music and applied those to playing in real time with live musicians.

“Music is a communal experience, always. That’s one of its powers,” says Mayer who embodies the drummer as a Renaissance man: he’s someone who thinks deeply not just about their own craft, but about art in the widest sense and its role in the world.

He can even give a 20-minute off-the-cuff history of the bass drum pedal, as we found out before launching into our questions…

In the Changing Time documentary about your life and career, you talk about the values that are expressed through music. Can you explain?

“It’s about the validity of any performance. What are the values behind any performance? When it comes to art, what is it that you have to say? Is it going to be something that’s going to elevate people, or make them stupid?

“That’s important right now. Why do we do what we do? If I may quote a Swiss colleague of mine, Fredy Studer, a drummer, philosopher and a great musician, he said: ‘In this life you need to find something that keeps you from going insane.’

"That’s really what it is. You find something that you can put your energy into. If you don’t have that, you’re going to spin out of control, so find whatever it is that brings you that bliss or pain or whatever it is that you need.

“I don’t think music is going to go away but I think the music industry as we know it is already dead. Something new is going to happen. I don’t know what that is going to be. The birth of the drumset was not like one guy had a great idea, it was an informal process that was informed by economic measures, saving money.

"You can’t hire three percussionists – a cymbal player, a snare drum player and a bass drum player – because the orchestral pits of vaudeville were tight. ‘I’m the snare drummer. Well, maybe I can play that bass drum somehow,’ so double drumming came.

“Vaudeville was the cradle of double drumming with the dance bands and then when the silent movies came, that was the death of vaudeville. People wanted to see movies but they were silent movies so drummers got a new gig making sounds, so the instruments grew. They added temple blocks, which could imitate horses and gunshots, so the ‘contraption’ happened.

“When sound recording came, that was the beginning of jazz because there was the opportunity to record improvised music, whereas before you couldn’t do that. I think something similar is going to happen again. Somehow creativity will find a way. It’s just right now we have to plough through it somehow.”

How do you approach the sound of your drums with Nerve?

“My general approach to my drum sound is it has to work in the music that I play. Sound is alchemy, the frequencies, low-end, mid, high, they have to play in synergy with the other stuff going on, which affects how much I have, how much room I occupy.

“You can have a huge bass drum if you play by yourself, BOOM! It sounds awesome, but if you have a bass player next to it he’s going to be frustrated because there’s no room for his frequencies.

"I’m always thinking about frequency and palette, so I try to get as much range in my set-up from really high to really low.

"If I only have three voices, I’m going to have one really high, one really low and one in the middle. Hi-hat, bass drum, snare drum.

“Okay, now I have a floor tom, which is very close to the bass drum for the stuff that I do because I’m emulating some of the two bass drum beats. Our music is not really tom-tom music, so I have this almost bass drum I play with my hands.

"I use those Big Fat Snare Drum sheets on it to muffle it, it has a very short sound and it almost sounds like cardboard when you play it, but it sounds great in the house through a microphone. I have the small rack tom that I took away from here [over the bass drum, in front of the snare], because I need that real estate for my hi-hats.

“As a physical thing it feels more comfortable to play those patterns if I have the hi-hats in front of me, so the rack tom is next to the floor tom. And I tune that really high so it’s completely different. I really want it to sound as alien as possible so when I hit it, it actually speaks out.

I use some electronic stuff, pretty standard, like some claps and some 808s, really super-electronic. I’m not trying to be too artisan about those types of things

“That’s my concept with the cymbals too. I choose cymbals that have very high contrast sounds, high and shimmering, then dark and oriental, dry, not a lot of spread. Not so much homogenous but more heterogenic so if I play them together they start to sound more interesting.

“I use those Big Fat Snare Drum sheets on all my snare drums, which makes them really dead sounding. So for instance I have a 13" in the middle and a 14" to my left. With the 14" I tune the snare head pretty low, then I overtighten the snares to the degree where they start to go ‘doooooosh’.

"If you didn’t have the muffling on the snare drum it would sound really shitty but with the muffling it’s almost like a gated reverb sound.

“With the 13" I tune that as high as I can without choking the sound. There’s a point where if you overtune it the shell starts to buckle and it begins to sound like a woodblock. I still like the crispness of the snare so I tune relatively high and if I play Amen Break, jungle-type stuff I just remove the Big Fat Snare, so I basically have four snare drums instead of two.

“I have a lot of stuff to augment the drums, like the Hoop Crasher from Sabian, but then I use some electronics too. The cymbals are all Sabian and pretty much everything that I play I also designed, like the Fierce hats, very dry, they don’t have a lot of spread.

"It’s not really the perfect hi-hat for a jazz acoustic trio gig, but for what I do, it’s perfect. You can really hear the difference when I play with the butt of my stick or the tip, it changes the sound completely.

“I have the OMNI ride, which is basically a hybrid between a crash cymbal and a ride. I have a 19" Fierce crash, which is heavily hammered, a very dark-sounding cymbal. I have a stack that’s made out of a perforated 13" Fierce hat top and a 14" hand-hammered Chinese.

“I use some electronic stuff, pretty standard, like some claps and some 808s, really super-electronic, I’m not trying to be too artisan about those types of things. I trigger my bass drum, that’s the only thing that I trigger.

"My latest toy is a do-it-yourself kit, it’s a clone of the Pearl Syncussion SY-1, it’s an electronic drum brain, two-channel brain, that was made by Pearl in 1981. It was only in production for two or three years, they’re really hard to get and very cumbersome. There’s a company in Sweden that makes a clone of that, so I just got one of those.

“It’s a really cool machine, it’s really temperamental and it’s completely analogue. You can’t save presets, you have to go the old Minimoog type of way. It has some really cool facilities, you can produce sample and hold-type effects, so when you hit the same pad in succession it changes the pitch or expression, the type of thing Billy Cobham has in the intro to ‘Spectrum’, really vintage electronic-sounding things.

“It’s a lot of fun to play and I have an Eventide H9 multi effects processor, which is controlled by an iPad. I use a lot of timed delays, compression, distortion. It works for me in improvisation settings because I can adjust the tempo on a whim.

"Everything else that’s not coming from my hands or those things is Aaron Nevezie, our engineer. He mangles my signal out there. I don’t hear everything that he does, I control the input, he controls the output.”

In contrast to the band’s live sound, why did you go for an acoustic format on the most recent Nerve album, After The Flare?

“That was an experiment. We do everything at The Bunker Studio, which is a studio in Williamsburg [New York], owned by John [Davis, Nerve bassist] and Aaron and also Jacob [Bergson, Nerve keyboard player] works there as an engineer, they’re all engineers.

"When we did the previous record, the self-titled one, as we were mixing it, they prepared the A room for a jazz recording session for the next morning.

“They had a little jazz kit and I started tinkering and playing around with it. John walked in and picked up the bass and we started to jam. Jacob sat down on the grand piano and we just jammed for about 20 minutes. Then Aaron went, ‘Yo, we’ve got to record that,’ and everything was set up for the next day.

“It sounded really good so we decided to put one of those segments from that jam on that last record and we called it ‘After The Flare’, which we thought was a nice touch, because we thought this is probably how we would play if a solar flare wiped out all electricity and we had to play a gig.

“We were falling back a little bit on the jazz vocabulary without actually playing the syntax of jazz and the form. The syntax is much more what we do when we play electronically. Then we decided, ‘Okay, let’s try to make an entire record,’ so we went into the studio and played all vintage gear.

“We recorded everything straight to two-track, no overdubs, this is what it is. We all recorded in the same room, no headphones, so I had to play really quiet like in the old days not to drown out the acoustic piano. It was cool.

“John showed it to John Patitucci, the bass player, and he really loved it: ‘It’s great, you’ve got to put it out.’ He was kind enough to write the liner notes for it too. I don’t know if we’re going to do that again or not but we thought nowadays you’ve got to have the licence to do whatever you feel like. There’s no record company executive to tell you what’s up.”

Are the Russians going to invade Norway? What is going to happen? We live in that reality where I think improvisation is going to become more important than planning

Is it important to have your own space to experiment, like your Nublu venue in New York?

“Nublu is a community of downtown musicians and I know everybody really well. We play at Nublu usually as a warm-up before we go out on the road. We’ll play for three, four days. It’s a small place. It’s like a little laboratory.

“You need one place where you can try things out because what we do is very improvisational. We have our modules that we fall back on, we don’t make a set-list before we go out, like: ‘Okay, let’s start with that, end with that,’ in the middle it’s always different.”

How does Nerve work when you play live? Is it like jazz where the songs have an A and a B part?

“Some of those modules are connected: ‘Okay, if you play this, you’re going to have a B part coming up. Once that B part is over, you have to invent the rest.’ We’re getting deeper into it. I just think what is required right now from an artistic standpoint is that you need to react.

“You can’t plan ahead anymore. The future is completely opaque, not just the next 15 years, but next Thursday. We don’t know what the f**k is going to go on. Are the Russians going to invade Norway? What is going to happen?

“We live in that reality where I think improvisation is going to become more important than planning, or just as important, and we have abandoned the improvisational factor of art, the real-time thing.

“We’re descendants of foragers, they were improvising all day long before they had cattle and agricultural structures: ‘It’s cold today, let’s get some meat, or it’s nice, let’s get some berries. There are no berries here, let’s go somewhere else.’

“That improvisational thing is a part of who we are and I think it’s going to be important to cultivate our ability to become resourceful on the spot and troubleshoot. Not just have a billion jokes that we know by heart, but to be genuinely funny.

“This is the way I see improvisation. I grew out of that legacy like all of us who play jazz and it’s a really rewarding incident when you go out there and you create something on the spot and the audience can feel it.