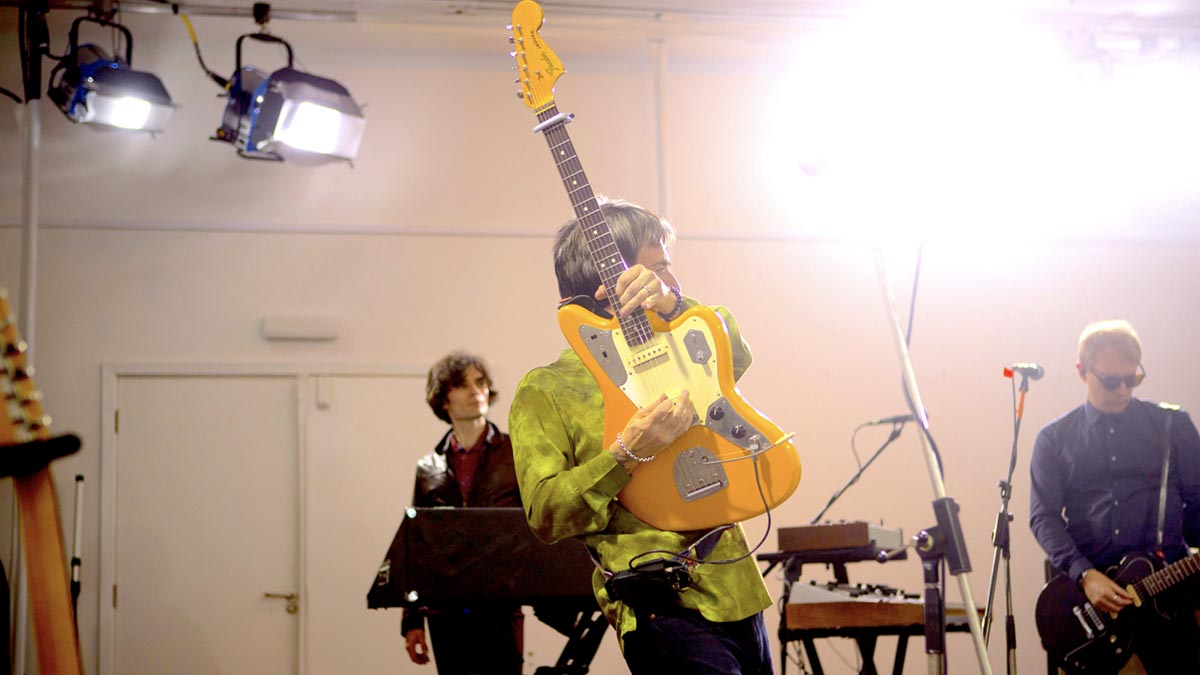

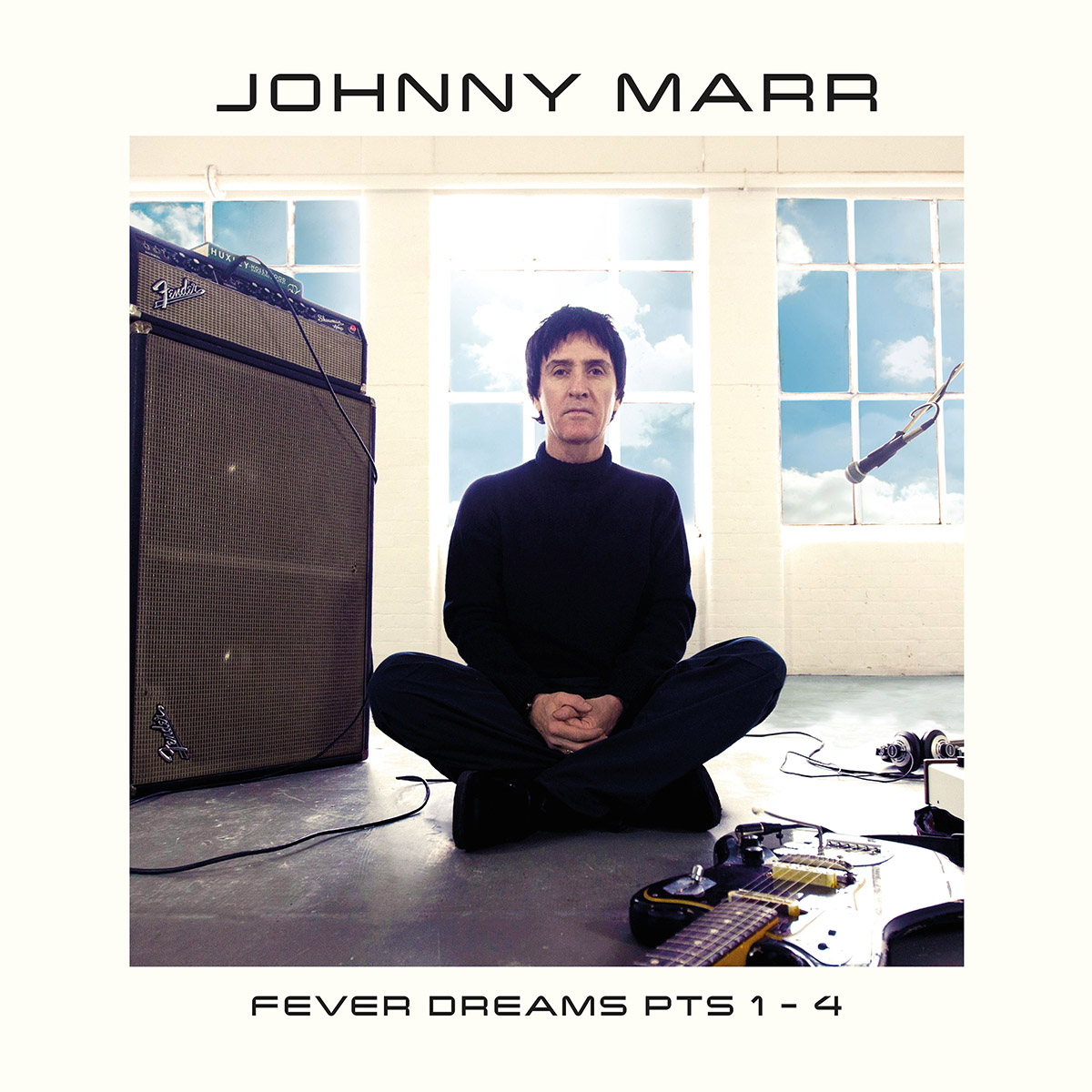

Johnny Marr: “I like synths but they don’t come anywhere near the fun you can have with a guitar, in every aspect”

Returning with the epic Fever Dreams Pts 1-4, Marr charts the evolution of his sound, and explains why the guitar retains a sense of mystery and wonder after all these years

When Johnny Marr first spoke to us about his new album, Fever Dreams Pts 1-4, it was February, 2020, and there were drum tracks that needed editing.

Even for an artist who takes great pleasure in production, drum edits are a chore, perhaps the one activity a recording artist would like to do less than speak to a journalist.

And so with a conversation ostensibly about the merits of the Fender Telecaster offering some respite, Marr took the opportunity to expound upon the making of the album, how his work on the Oscar-winning Bond score with Hans Zimmer et al informed his approach, and, ultimately, what role the guitar assumes in all of this.

Fever Dreams reframes the guitar’s place in Marr’s sound; it presents it in different contexts. Maybe that has something to do with the scale of the project. A double album presented in four acts, Fever Dreams is immersive and eclectic, a release on which the riff-orientated guitar songs share space with electronic-led arrangements.

For a record that started before lockdown before taking shape across much of that shapeless, timeless era, it has its share of celebratory moments, not least opening track Spirit Power And Soul, a “big electro banger” to reestablish communion between band and audience. There is an electronic pulse coursing throughout.

Two years and two weeks to the day later, Marr rejoins us on Zoom to explain that the sounds we hear on Fever Dreams are not simply a question of scale; it was seeing the potential for the guitar to inhabit new territory, and recognising that you can redraw the parameters of your sound for your fourth album, especially when the ideas keep on coming. As any artist worth their salt will tell you, when the ideas are flowing you stay at the wheel.

The following interview is edited together from both conversations, and it finds Marr revisiting early creative epiphanies with The Smiths, when what was considered pop and what was avant-garde was ripe for subverting. He also shares his thoughts on how technology has has augmented the recording process, for good and for ill, and declares that – no matter how his sound may evolve – the primal appeal of guitar playing remains eternal.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Did you know from the outset that Fever Dreams would be so epic?

“I did. I am thinking about the record the whole time while I am making one, to a ridiculous degree. I have heard about this thing called a work-life balance but in my case it doesn’t exist. When I think back to the start of it, I had this subconscious idea that it was going to be epic, and – I know this is obvious – but it had to evolve, it had to evolve from the previous record, Call The Comet.

When I was writing I just thought, ‘This is going to sound good, f**k it. If it sounds good, whatever!

“That was really well liked, by fans particularly. It was critically acclaimed and there was a lot of ‘it’s Johnny Marr’s best solo album’ and all of that. I guess I was feeling a certain amount of need to better it, and for it to be bigger.

“I am very lucky to have a great group. I have had the same band all the way through my solo career, so that is about nine years now. But the actual writing of the songs and the making of the demos I do myself. It is not like when I was in The The or The Smiths or The Cribs, where there’s four of you knocking stuff out. I present the songs in quite a detailed way to the band, and when I send them the demos they are very complete. It is quite a big task.

Was it the sort of album that became difficult to finish it gathered pace and size?

“It wasn’t difficult to finish, just because I’ve been doing it for so long. I’ve been making records since I was a teenager and I guess I just know what it takes. A big part of what I have been doing is as a producer. A lot of musicians are like that in this day and age with the change in the studio and the way that technology has gone along – we are all producers now.

“I learned a lot of stuff on those Smiths records – with all the bands I’ve been with – and either being in the hot-seat from a really young age, with really good engineers, and being around some legendary producers like Steve Lillywhite and Nick Launey.

“I often walk in with a producer’s head on: ‘What are we going to do today? When are the drums going to be edited?’ It’s a technical and creative job for me. It’s time management. I’ve always got whiteboards up. That was one of the things I brought in with Modest Mouse. A lot of professional musicians will know about that but it is really good to have some kind of structure.”

One of the things on this record is how the guitars and the electronic elements are held in equilibrium. Was that a conscious decision to strike that balance?

“I definitely had a wish to make the first single an electro song, which is why Spirit Power And Soul is how it is. I thought it would be a really exciting thing for fans and the band to have a really big electro banger.

“One of the early songs was Hideaway Girl, which is an almost Queens Of The Stone Age kind of thing, and I could hear the band in my head when I was coming up with the tune. And also, the other one is Ghoster, which is another organic, band-orientated thing.

“The first few songs I wrote were very much with the band in mind but then I went off to do the Bond movie. Whilst I was on the Bond movie, being around Hans and the team, you are around lot of technology, and we all like equipment, musicians, and that fed into [the record].

“I came up with Receiver while I was working on the movie, which has this almost cinematic [hums tune] and when I done it I thought I hadn’t done anything like that in any band I’ve been in. Well, maybe with The The…

The very first solo song I put out, The Right Thing Right, wasn’t to ape Northern Soul but it was to have that exact same feeling, that sort of exuberance

“But to answer your question, when lockdown happened, I wasn’t really supposed to be in the studio but I was going, ‘Hmm, well, what about these 30 virtual synth plugins I’ve bought over the last three years that I have never really tried?’ I was writing really quickly. I got really into the Arturia Spark drum machine, so I was programming a lot, but it was just a way of hearing good stuff out of the speakers and then being able to play guitar on it.

“Arial is a mixture of electro sounds, an electro kind of backdrop with that kind of ‘80s riff, and I was just enjoying the process of programming, and exploring all of the stuff that I had bought. But also, half of my brain was going, ‘This sounds different to Call The Comet.’ It excited me. It snagged me, because it wasn’t sounding like Call The Comet. It was sounding all shiny and big and new.”

You’ve spoken about Fever Dreams requiring you to look inward, it being maybe less urban, but there’s still something distinctly Manchester about the songs. There are lots of ‘going out’ songs. Talking about Spirit Power And Love, it sounds like you’ve taken that Northern Soul spirit, something that might have been heard at the Twisted Wheel, then reinterpreted that through your sound and sensibility.

“Nice! I’ve got another song like that, the very first song that kicks off the first solo album, The Messenger. Thank you for that. I’m glad you picked up on that because we’re talking about a feeling, and the very first solo song I put out, The Right Thing Right, it wasn’t to ape Northern Soul but it was to have that exact same feeling that you are talking about, that sort of exuberance.

There is a lot of fun in the physical art of making records and I am still very enthusiastic about that

“And I think you are also right with the Manchester thing, because there is probably a thing I have done with electronic [instruments] and maybe in the guitars in the Smiths days, with what people associate with my sound, and some of my peers – 808 State, New Order, of course – and when you hear those kinds of sounds your mind thinks about the northwest of England, and I think that’s something to be proud of.

“Spirit Power And Soul, I was thinking about Cabaret Voltaire. The beat, some people would think it sounds like New Order, and that’s not incorrect, but that is because all of us – Cabs, myself, A Certain Ratio, New Order, Pet Shop Boys – were into Giorgio Moroder, Kraftwerk, and Human League. This place that I am in now, it has an industrial association to me. It is in an old factory. So I am glad that it all sounds like that. That’s good.”

You talk about your peers back then and it is interesting, because sometimes it is hard to parse all the influences because everyone was using the same gear. Synths were so new and expensive, and that in itself established a sonic vocabulary for that whole era. These ideas and sounds got shared around.

“Yeah, that’s an exciting thing about culture, I think. The technology now is so vast. You can have literally hundreds, thousands of sound sources on your laptop, and then you start getting to this option fatigue, and maybe, if you’re not careful, you’ll have a generic sound.

“I am very conscious and always have been of having parameters sonically and aesthetically, setting myself parameters… But, now I say that, one of the things that makes this album different is that I actually was just like, ‘Whatever!’ on this record. [Laughs]

“You see, on The Messenger, and on Playland – and the band will tell you, this is a fact – I was like, ‘We don’t use loops. We certainly don’t use hip-hop loops. We don’t really use string simulation, and if we do we use that Yamaha string machine, which Magazine used to use. If we use string simulation it has to be synthesizers. There were a whole load of don’ts.

“I suppose I’ve got to album four now and without being particularly conscious of it I just dropped that, which is why there is a song like Lightning People on it. That song has Simone [Butler] from Primal Scream. It has choir backing vocals. There are still no hip-hop loops per se, or strings, but I definitely expanded… To be honest, when I was writing I just thought, ‘This is going to sound good, fuck it. If it sounds good, whatever!’”

Perhaps it’s a question of feel, or a sensibility that allows you to cheat on your parameters for the good of the song.

“Yeah, from being a boy, when I was making tapes, my really early attempts at songwriting, when I got my first drum machine, I could hear a picture emerging on my very early demos. This was pre-Smiths, and I would often be like, ‘Does it sound like a record?’ And I am not talking about technical things about compression. I’m talking about, ‘If I wanted to put 10 guitars on there I would have to make it sound like four or five.’

“I got a sense – and I’m still like this – of, ‘What kind of record are we making here?’ I think I am someone who makes records and I have to write a song to make a record – I think of myself as a record maker. It’s different when I am out with the band onstage. That’s a different mentality. But I have a consistent sort of judgement of what’s going on, which probably makes me a pretty good producer.

“I used to study records at 12. I used to study them, and I would play them over and over again, and be like, ‘Oh, that’s quite clever; that’s just dropped out because this has come in. I see why they’ve done that.’ I just learned to do that through study.”

There’s a grammar to songwriting and production, how sounds stack with each other, and how you use your vocabulary of sounds to make a song and a production work.

“I am not a master of the dark arts or anything, though I have been doing it a long time, but I have to say, I hear records made by young people, certainly younger than me, on modern technology, and I marvel at the skill of it. And I am talking about spatial awareness. Grammar is a really good word for it.

I would hear the way bands like Sparks will do something with guitar and piano, and you would hear this little organ thing come in, the clever backing vocals… I used to imagine the process

“It is almost a given by now. Of course you have big name producers like Inflo, and Paul Epworth, and people who are very skilled, almost setting the modern template. But you hear so so many young bands whose bass player is the engineer, and they are mixing it in their mate’s studio – I won’t say a bedroom because I am not sure you can do it so well on headphones – and people have got really, really good at putting records together.

“I think that’s great. If it is a good listen, it’s a good listen. When I was a kid, I would hear the way bands like Sparks will do something with guitar and piano, and you would hear this little organ thing come in, the clever backing vocals… I used to imagine the process in the room.

“Frankly, it has to be said there is a lot more fun in that, in getting some of your mates round. I did that with a lot of guitars stuff on The Smiths with John Porter at three o’clock in the morning, and I’m hitting the chord as he’s hitting the tremolo pedal. ‘Oh no, do it again – it’s not quite in time.’ Whereas now, you’d just move a mouse. There is a lot of fun in the physical art of making records and I am still very enthusiastic about that.”

It’s related to performance, and we sometimes have to remind ourselves that each take is a performance and it counts. It’s funny when we talk about making records because it is still such a young art form. We’re only at the beginning.

“Unfortunately we have got used to listening to a lot of music that is not what you are talking about; music that is just cut and paste. And we have got really used to it. It drives me mad… The worst, man, is when you are sitting on a plane, waiting to take off, and it’s really deafening, generic. I think it’s really bad for you! It’s bad for me anyway.

For a lot of my clean sounds my go-to is my 1984/’85 red Les Paul... That has been on more records that I have done than any other guitar

“It is audio toxicity. It is horrible. I am getting ever more sensitive to it, that cut and paste thing. Overall I am still overawed about the skill of young musicians. It’s all about taste at the end of the day. There is a lot of people doing a lot of good stuff out there.”

What were the key guitars for this record?

“There is my signature Jag always in the mix, obviously. And then there’s a few go-tos. I have a Yamaha SG-1000, which I use a lot. I use two different 1973 Les Paul Customs a lot. For a lot of my clean sounds, people might be surprised, but my go-to is my 1984/’85 red Les Paul that I got for The Smiths’ second album. That has been on more records that I have done than any other guitar. I used that through the Cribs, Modest Mouse, everything.

“And then for the 12-strings I used the [Gibson] 1275 double-neck because it is the best electric 12-string sound. I used an early 2000s Telecaster. And for the acoustics, I used an Auden custom 12-string that they made for me, and a six-string, and they are absolutely great.

“Sometimes I use them for tracking, double-tracking arpeggios particularly. But you hear them most effectively on this song Counter Clock World where I am doing this Eddie Cochran kind of thing. That is a 12-string and a six-string tracked. Those are the main guitars.

Occasionally I will use my old Gretsch 6120 with something like a very expressive whammy bar thing but my signature Jag takes care of a lot of business

“I’ve got a ‘60s P-Bass, two ‘60s P-Basses that I use, and what else? I have one of my signature Jags which is high-strung [E, A, and D strings tuned an octave up, wit G, B, and E strings in standard tuning] that I took the finish off. I might be tripping out but I think that because it is now pretty dried out and it’s just down to wood it complements the high-strung zing pretty well. Occasionally I will use my old Gretsch 6120, with something like a very expressive whammy bar thing, but my signature Jag takes care of a lot of business, y’know.”

Absolutely, it’s like the one pair of jeans that looks good no matter whatever else you’re wearing. We were talking Telecasters earlier and how Tim Mills at Bare Knuckle wound a Yardbird pickup that ended up in your Jaguar.

That cross-pollination of Fender designs is very exciting. It’s like if guitar tones were the Waltons, all quite different in their own right but you can instantly tell which family they’re from.

“A hundred per cent. Obviously, there are a lot of things you can say about Telecasters, about their functionality, about the simplicity of them, the fact that like a lot of great things they got the design right straight out of the gate. The lack of unnecessary switches, options, means that they are very practical. Fewer things can go wrong on the road or onstage. They do the job very well. All of those things are part of the Telecaster’s story.

There are a few good examples of punky Telecasters. There is a no nonsense, stripped-down, to-the-point functionality about them which suits that attitude

“But for me, if you are talking about tonality, what I was looking for from my Jag – which I wanted to bring from my Telecaster world – was from Joe Strummer, and I think that he had something going on in the Clash records which wasn’t about rockabilly or that classic kind of piercing, very present, clean, focused sound; it was that clang. That was what I wanted from the Yardbird pickup that Tim was doing at Bare Knuckle, that went into my early 2000s custom ‘60s reissue.”

That’s right. You like a darker clang on your Telecaster.

“It is such a specific thing that I am looking for. It was a no-brainer that I would put that in my Jag. You’re right, there are all these common yet different aspects as you go through the Fender permutations. Tone and sound is quite a difficult thing to put into words sometimes, but guitar players and guitar fans tend to have a bit of shorthand! [Laughs] We know what that sort of out-of-phase Strat thing means!”

Exactly, it is a whole language unto itself that makes everyone else in the room turn off and go blank when we start talking like that.

“Yeah, yeah! Exactly. [Laughs] But, that was really important for me, that punky sound. I wanted that from a Tele. I had that association with Teles that I knew was not necessarily the thing that is usually talked about. There are a few good examples of punky Telecasters. I guess there is a no nonsense, stripped-down, to-the-point functionality about them which suits that attitude.”

And it suits guitar players. We are simple creatures.

“I think so! On the one hand, guitars are very simple to plug in and play for the most part, but, speaking personally, I can get pretty nerdy, too, and I have had to find the right balance.

“It was an interesting thing for me to think about when I made my custom guitar; not being complicated for the sake of it, being straightforward so that most regular guitar players would not get frustrated or bored, but at the same time have loads of options which I like. But, essentially, we all get to the place where you do what you do, you know what you like, and you wanna get there pretty quick.”

Listening to you over the years talk sounds and chasing new tones, and styles, you are something of a seeker.

“Yeah, thanks. I’d say that’s true. [Laughs] With most things, I am, yeah. That is a nice thing for me to think about. It is one of the things that attracted me to the guitar; there is still a mystery to me about it and still things to find, and you can look at it as being quite a simplistic instrument, which again, the Telecaster – we keep coming back to it – and the only guitar I can think of that would be more simple than it would be a one-pickup Les Paul Junior.

“I am always thinking that there are so many things I don’t know about sound and what guitars do that I am excited to discover. That is before you even get into the realms of pedals. So yeah, I am always seeking!”

Marcus King once told us that the journey is the destination…

“Well that’s a very zen way of looking at it. And I think that is right. Being a guitar player can be a journey for life.”

You are cast the great pop songwriter but also the seeker, chasing weird sounds, and then there’s that tension in getting the two sensibilities to meet. How do you make sure the song always lands on its feet?

“It helps if you like things that are catchy, because I am such a melody freak. But I also like things to be a little heady. There is loads of music, pop music and otherwise, that is cleverly disguised, that is very melodic, and that’s all well and good, but with everything in life I always want it to be various degrees of psychedelic.

I love pop but it is not enough for me… I never want it to be too straight

“I guess that’s what I mean by heady. I am looking for that. With The Smiths, How Soon Is Now?, Well I Wonder, That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore, they can be considered a ballad but there is a different kind of emotional dimension to it. Or with The The, Good Morning Beautiful and Dogs Of Lust have got more of a three a.m. testosterone vibe but are still slightly otherworldly. I am always looking for that, even in a pop song. I love pop but it is not enough for me… I never want it to be too straight.”

There’s a dreaminess to some of your writing, and when you put that after hours vibe in a pop song you can really subvert it. It would be fascinating to hear you work with Angelo Badalamenti and David Lynch.

“Well that’s a nice thought. Dreamy is really good. I like that. Even in the daytime, dreamy is pretty good. Because, I have said it many times, but I do believe you are what you play, and, ha! I try to be a functioning person but dreamy is absolutely fine by me. I was like that as a kid, and I have always tried to keep that quality.

“The stuff that I have done over the years that I really like best is, hopefully, a good combination of otherworldly but accessible. I am not interested in being in the ghetto because I think it is almost too easy to make an interesting noise and call it art. I think you really hit the bullseye when you do something really interesting, call it art, and people want to listen to it… On their way to school, or on their way back from work, on the train, and it puts them in a slightly different place.”

You are kind of hot-wiring the brain, giving them something catchy, but with a deeper dimension. The Beatles were masters of that sleight of hand.

“Yeah, that’s a good example. There are so many great examples. For me, growing up as a kid, it was Roxy Music with Street Life or Both Ends Burning. You listen to Both Ends Burning, that was a pop single! And the attitude of the singer and what he is saying, and the way he is putting his voice across, and just the start of it… That is the best kind of avant-garde, I think.

“They were the values I grew up with. We were excited to bring that to Smiths records, whether it was Sheila Take A Bow, starting off with the brass band playing [hums intro], starting a pop single with that. That was a subversive act. The start of The Queen Is Dead, [with the sample of Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty from The L-Shaped Room], the musique concrète aspects, fade in/fade out, all those kind of little arty things are subversive.

“Once the music is sorted out, you can work on the presentation. All of these things are why I think pop music is art, and it is art with a capital F-U-N.”

Sure, we don’t need silk gloves and airs and graces to appreciate art on any level. You stare out the window to it. You turn it up loud on a Friday night.

“Yeah, and you can walk into your classroom to it and send out a code that says, ‘This represents me and my kind of philosophy,’ which is quite important for a 15-year-old.”

Do you think that sensibility that you have, is from that sense of growing up and maybe being a little dissatisfied with the mundane, and the greyness – that many of us who grew up in similar British urban environments can relate to – that pop culture and art creates a world that is all the more interesting to live in?

“Yeah, well I think you just answered your own question there. That is what it’s for. That’s why you identify with [certain] groups, and the sound of pop music. Aside from the aesthetic, what sound does, what makes it the most exciting art form for me – and I love great moves, great directors, and I love great painters – is there is something so physical that an amazing intro will give you. For some people, that might be the start of Smells Like Teen Spirit. For me, it is often done on a guitar.

The stuff that I have done over the years that I really like best is, hopefully, a good combination of otherworldly but accessible

“And there are plenty of records that I like the sound of that don’t involve the guitar, say, Blue Monday, or some great Buddy Rich song, but there is just something about a record starting with a riff that is very different to looking at an amazing photograph, or an amazing painting, even if it is saying the same thing.

“We live on a quirky, ever more quirky, eccentric little island that has amazingly produced lots and lots of those little moments. All of us, as music fans, can go on forever with our playlists, and say why this stuff is so important. I feel very fortunate for it to have been my life and for it to continue to be my life.”

At the risk of being overly romantic about it, there’s something magic even about the words electric guitar. Perhaps that’s the nature of the beast; there’s something endless about the instrument’s potential.

“It is the nature of the beast, but it is also the nature of the person, and guitar players are definitely a breed. I identified very early on, in my teens, that the guitar could be an utterly romantic object to be fetishised – gazing at them in guitar shops or catalogues, talking to your friends about them, or listening to Django Reinhardt, reading the story of Djanjo Reinhardt, or Jimi Hendrix, et cetera. But, at the same time, you pick it up and it is an electronic machine.”

You can be as romantic or utilitarian with it and get what you need from it.

“Yeah, occasionally I’ll pick it up and play the dumbest kind of riff. It might be Upstarts, or on my last album, The Tracers [hums the riff], which is I guess is sort of a throwback to American psych garage, and I was a long way from thinking about Lenny Breau or John McLaughlin. I was trying to be as dumb and to the point as possible.

“There are other times, particularly when I have been in the room with Karl Bartos, where I feel like, ‘Well, if Kraftwerk were a guitar player, what would they do?’ There are all these associations we have with guitars, which is fantastic, and that is what you’re talking about with the romanticism and the fetishising of it, which, God, I’ll never lose, because I’ve had that since I was a boy. Then on the other hand I like the idea of never forgetting that it is [just] an electric instrument.”

Have you had any gear epiphanies on this record?

“The amount of boutique devices in the world right now is astonishing, and they’re so much fun, and I am just a big a sucker as anybody for experimenting with those things. But I have been working with Boss a little bit on the new GT-1000 Core to just see how much programmable options and craziness can be put into a little device, and pushing the limits of that. Other than that, I’m not going to tell you my secrets. You’ll have to read the manual! [Laughs]”

The riffs you mentioned, when you hum the melody it could be a children’s song, really elemental. But you can really change its character just by changing the guitar sound.

“With the stuff I have been doing on movies, for example, I have been using the 12-string a lot, like the electric 12-string on Inception. Most of the stuff I have been doing on the new Bond film are these really bugged-out noises that we all know about but that just cannot be done the same way on a synthesizer because it is to do with wires. It is to do with steel and wire and the microphonic nature of pickups, and spring reverbs, and that’s even before they are manipulated.

“I have had plenty of interesting sounds out of synths, particularly when working with the band Electronic, which were experimenting in guitars. There is a guitar solo on a song we did called Forbidden City, which is entirely a conceptual solo. I wanted the guitar solo to be like a pop-art painting but still melodic.

“That was me sampling a load of notes I was playing through Marshalls, and then playing it with a MIDI guitar so it still felt like I was playing with a guitar, but through a keyboard, and then with a Doppler effect on it. You can go to that extreme.

“What really excites me about working on movies at the moment is actually being in competition with these incredible synthesizer programmers and sound designers, and bringing the guitar into it and surprising everybody.”

A post shared by Johnny Marr (@johnnymarrgram)

A photo posted by on

That’s the challenge. There’s also all that free space to run into sound-wise, that might on occasion be closed off when you’ve got a song to hold together.

“I’ve been working on it for quite a while now, just stuff you wouldn’t even recognise as a guitar, but if you took it away the scene would be different. And I guess you could try and emulate it on a synth, or with a violin or whatever, but it is to do with the electricity and the fact that it is steel and you’ve got different ways of bending things with your fingers. It’s just a different physical beast. And I like synths. I like synths but they don’t come anywhere near the fun you can have with a guitar, in every aspect.”

- Johnny Marr's new double album Fever Dreams Pts 1-4 is out now via BMG. Johnny Marr will perform live at the BBC Radio 6 Music Festival in Cardiff 1st - 3rd April, before a UK arena tour with Blondie beginning 22nd April at Glasgow's SSE Hydro.

- Johnny Marr on tour in April

- Fri 1st Guildhall, Gloucester TICKETS HERE

- Sat 2nd Old Fire Station, Bournemouth TICKETS HERE

- Sun 3rd BBC 6 Music Festival, Cardiff

- Tues 19th Foundry, Sheffield TICKETS HERE

- Wed 20th Students Union, Northumbria University TICKETS HERE

- Fri 22 The SSE Hydro, Glasgow (with Blondie)

- Sat 23 Motorpoint Arena, Cardiff (with Blondie)

- Mon 25 Pryzm, Kingston-Upon-Thames (with Banquet Records) SOLD OUT

- Tues 26 The O2 Arena, London (with Blondie)

- Thurs 28 The Brighton Centre (with Blondie)

- Fri 29 Bonus Arena, Hull (with Blondie)

- May

- Sun 1 AO Arena, Manchester (with Blondie)

- Mon 2 Liverpool M&S Bank Arena (with Blondie)

- Wed 4 First Direct Arena, Leeds (with Blondie)

- Thurs 5 Motorpoint Arena, Nottingham (with Blondie)

- Sat 7 Birmingham Utilita Arena (with Blondie)

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

“Every note counts and fits perfectly”: Kirk Hammett names his best Metallica solo – and no, it’s not One or Master Of Puppets

“I can write anything... Just tell me what you want. You want death metal in C? Okay, here it is. A little country and western? Reggae, blues, whatever”: Yngwie Malmsteen on classical epiphanies, modern art and why he embraces the cliff edge