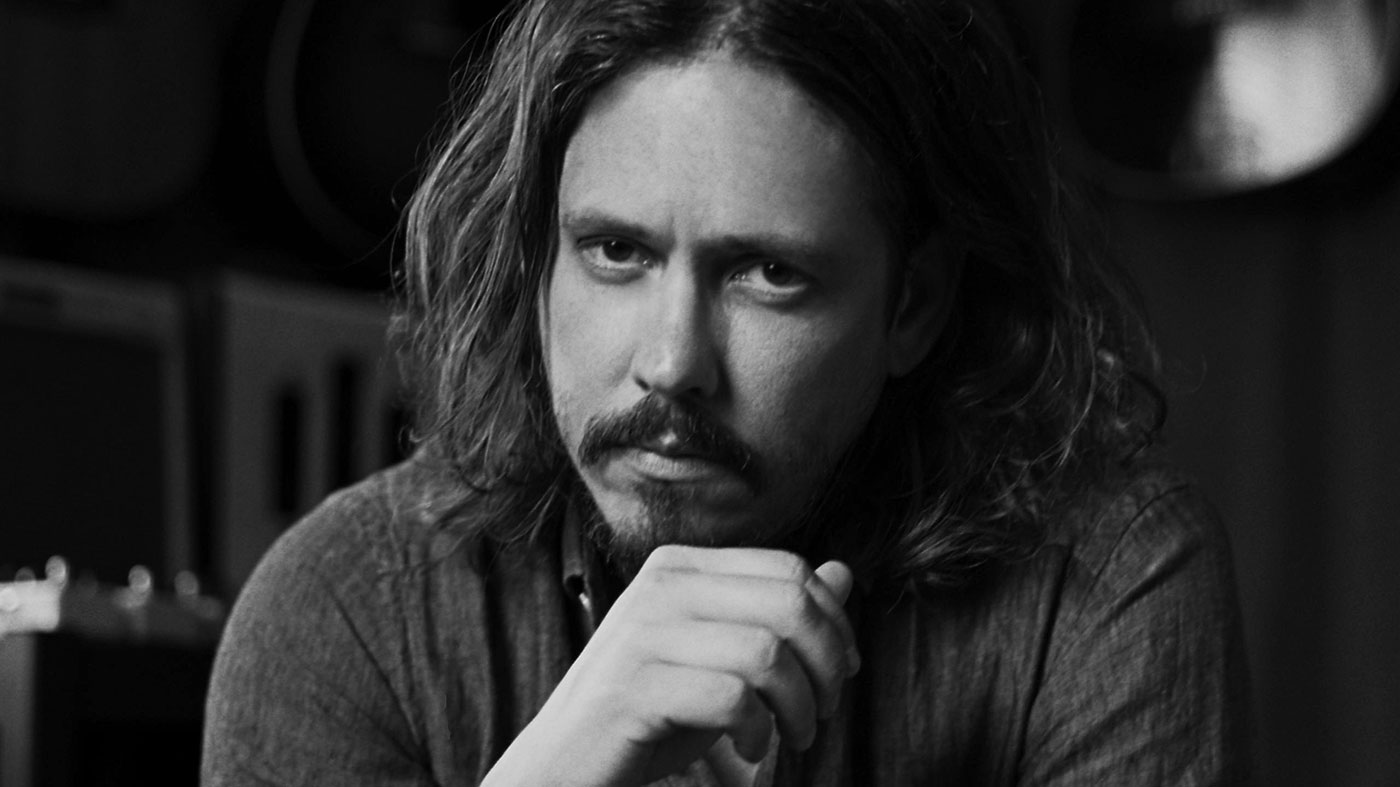

John Paul White on making his first album since The Civil Wars: "I didn’t know if I would do this again"

Beulah in-depth with the Grammy-winning songwriter

Introduction

After a long hiatus, John Paul White, formerly of The Civil Wars, is back with new album, Beulah. We talk to the Grammy winner about travel, bells and whistles and William Blake.

It’s all go for John Paul White at the moment, as he releases his first solo album since 2008’s The Long Goodbye, which was overshadowed by his work in the Grammy-winning duo The Civil Wars, who eventually came to rest in 2014. We catch up with him in the midst of touring the wonderful new Beulah record.

It’s kind of surreal; I didn’t know or care if I would do this again, to be honest

“I’m on my way across Arkansas, so if I lose signal, please bear with me,” he begins, in a friendly Alabaman drawl. “We’re driving across the desert to LA to play at a place called the Troubadour in a couple of days' time. I was adamant I wasn’t going to miss my wife’s birthday, so now we have a lot of travelling to do, but I’m kind of excited about it. I may not ever wanna do it again, but it’s fun this time so far!”

The travelling side to the musician’s world is something White is less familiar with these days, having not released or toured an album since the demise of The Civil Wars; what made him write another album, we wonder.

“It’s kind of surreal; I didn’t know or care if I would do this again, to be honest,” he laughs. “We have a little studio in the Shoals called Single Lock Records, so I’ve been helping other people make music and writing songs with artists, for their records, and I’ve been completely happy doing that. This came out of nowhere, but I’ve been enjoying it. I actually tried not to write Beulah, so when the songs came into my head I paid no attention to it.”

He gives a small laugh and says that when he told his wife he was going to write, she was “incredibly surprised”, but he went and rattled off eight or 10 songs in three days.

Dormant energy

“I don’t even know where it came from,” he admits. “I just wanted to capture it. Strangely though, I automatically began thinking, ‘I wonder what people will think of this, if they will be moved by it or will connect to it.’ It was unusual, because I generally didn’t care what people thought about what I did, but with this all of that came flooding in.”

With analogue, if there’s a flaw, we have to ask ourselves if we want to go back and re-do the whole thing, or keep the flaw

There is a freshness across Beulah’s 10 tracks that will reassure any listener that, songs excepted, the album’s crafting was smooth. “Maybe because I was quiet and dormant for so long, this one has a sense of energy,” he considers, after a pause.

“I’m really happy about that, because I didn’t set out to accomplish anything in particular. There was no certain sound, be it small, large, more guitars, less guitars, or anything else. It was more that as the song was written, it made sense to portray it in a certain light. And also,” he continues, “I have had the fortune to make records with local artists, so I was able to take time to decorate these things how I wanted to.”

The studio time and space helping or hindering the creative process is a significant part of the whole recording process, it seems. “It was definitely liberating not having a clock ticking on the wall, or another band trying to get in there. But,” he states, with a chuckle, “that can be a curse and quite overwhelming and it can lead to overproducing. I was lucky enough to have my friend [Alabama Shakes’ keyboard player] Ben Tanner there to be able to tell me when it was good. He would say ‘I know you could technically sing it better, but I think that was the one; that take had it.’

“The thing about digital versus analogue recording,” White muses, “is that with analogue, you have to make choices. With digital, you can keep polishing until you achieve your ‘perfection’, whatever that is! With analogue, if there’s a flaw, we have to ask ourselves if we want to go back and re-do the whole thing, or keep the flaw. We recorded Beulah digitally, but we kept an analogue mentality, so we would take the cuts that felt right and keep the flaws.”

Acoustic core

But we all know that the best records are the ones with the mistakes don’t we? “Yes!” he immediately answers.

“And it’s not a coincidence. If you smooth it all over and put everything in exactly the right place, you take the human element out of it. These things need to breathe and feel real and feel live, rather than a painting in front of you. Yes, sir.”

I’m a sucker for those Beatles records and ELO and Rufus Wainwright and stuff like that, with the orchestral elements

The album does feel live and cohesive, but it has its own textures present throughout as well. “Well, to be honest, I get bored pretty easily,” he laughs. “So as I’m listening, it needs to keep my interest as well as everybody else’s. Luckily, we have a lot of bells and whistles in the studio to enhance the sound. I’m a sucker for those Beatles records and ELO and Rufus Wainwright and stuff like that, with the orchestral elements. Those albums have a lot going on, but they can maintain an acoustic core, so they can be very simple or very grandiose.”

The acoustic core is what feels important on this new album, and it’s always there in the songs. “That’s how they all started and what they all grew from. I remember somebody telling me that they went on tour with just a guitar and quickly found out that parts of their songs were boring without the guitar solos and drums. That has become a test for me, so I make sure before anybody puts another note on there that I feel good about the basic song top to bottom as it is; and with these ones I do.”

Before moving on, we touch on the interesting album title, Beulah and its significance. “The word Beulah is a word we use around the house a lot,” he explains. “It’s a term of endearment; I call my wife and daughter Beulah; my dad used to call my sister Beulah. It has biblical and divine connotations,” he continues, “but my take on it is from William Blake. He had his own spiritual mythology and one of his terms was Beulah; he deemed that it was a place you could go for spiritual healing, to re-centre and get your lot together, before returning to earth to start anew. And I feel like that’s really where this record is coming from.”

Gear

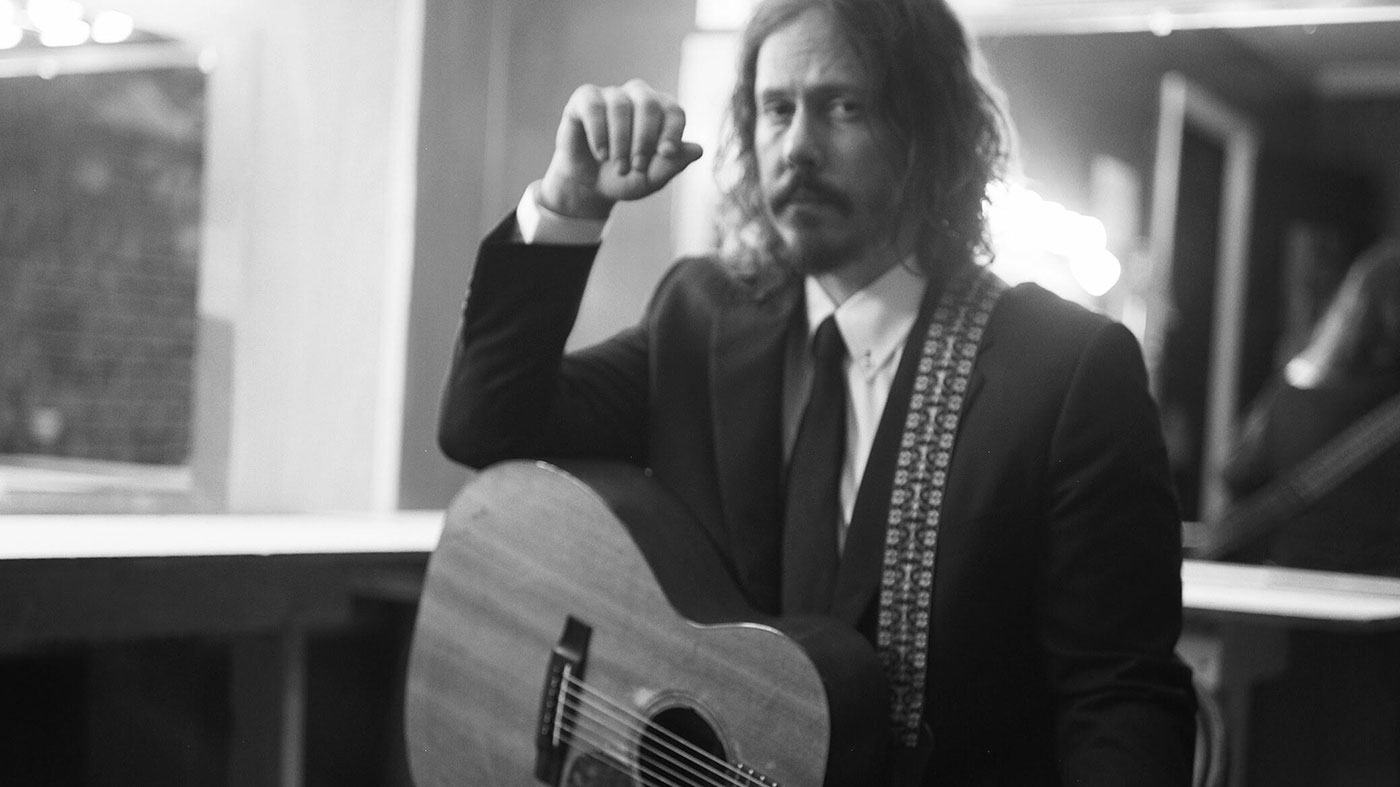

“In most of the photos I’m in, I’m holding a Martin 000-18 from 1957. It was given to my family by a friend, and when he brought it over he looked at us four kids and said ‘surely one of them will play.’

I’m of the belief that certain songs would not be written without a certain instrument

“So it sat there until I was 15 and wanted to play guitar, but I didn’t want an acoustic guitar, I wanted to play electric! So I took this Martin and tried to pawn it, and luckily the storeowner was a good guy and he said ‘you don’t know what this is, do you?’

“He took the guitar and looked it up and came back and said ‘keep hold of this one man, you’ll really hate yourself if you sell it.’ I still give that guy love, his name is Mike Looney, and I’ve written most of my songs on that Martin.”

He pauses a moment. “I’m of the belief that certain songs would not be written without a certain instrument. I also have an old Gibson L-OO, and on that I write completely different songs that would never have been born on the Martin. Guitars are very important tools for me, and I like to play to their strengths and stay away from their weaknesses.”

Beulah is out now on Single Lock Records.