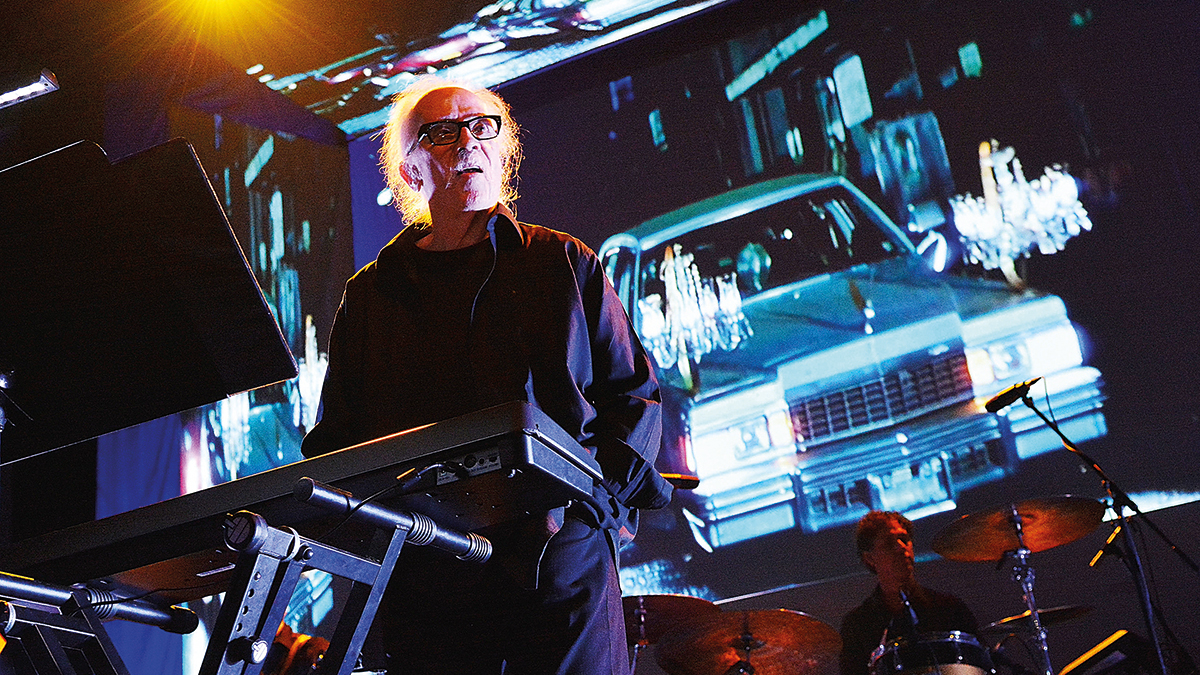

John Carpenter: "My son was kind enough to figure out the MIDI for each of those songs, so I’ve not had to suffer through listening back to too much of my old stuff.”

The master of horror returns to the world of soundtracks

MusicRadar's best of 2018: An undeniable icon of ‘genre’ cinema, John Carpenter is responsible for a string of genuine classic films that shaped the face of horror and sci-fi through the ’80s and ’90s.

To many though, Carpenter has been just as influential for his music as for his movies. From his debut picture Dark Star onwards, Carpenter has composed and recorded the soundtracks to most of his films, leaning heavily on raw, minimal synth compositions that combine his love of riff-driven rock with the influence of acts like Goblin and Tangerine Dream. Despite turning to synths originally out of necessity – providing a way to replicate the feel of an orchestral score on a low budget – they quickly became a defining element of his onscreen aesthetic, used to create dread-inducing soundscapes and build tension through driving arpeggios.

There’s no doubt that Carpenter’s compositions have had a major impact on the landscape of electronic music. For many musicians who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s – this writer included – Carpenter’s films provided early exposure to synthesised music, and would sow the seeds for a lifetime love of ambient, electronic and experimental music.

In recent years, Carpenter has shifted away from filmmaking to concentrate on his music. In 2015 he released his first full album, Lost Themes, a collection of tracks written alongside his son Cody Carpenter and godson Daniel Davies, devised as soundtracks to imaginary films. That was followed a year later by Lost Themes II, as well as the 2017 compilation Anthology: Movie Themes 1974 – 1998, in which the trio re-record a number of Carpenter’s best-known compositions.

This October he returns to the realm of film soundtracks for the new Halloween sequel, creating a score that pays homage to the iconic themes of his 1978 original, while subtly updating the sound palette with driving drum machine patterns and modern, digital drones. Ahead of the film’s release, we sat down with Carpenter to discuss his musical journey across the 40 years since he first composed that iconic theme.

The new Halloween soundtrack walks a careful line between vintage and modern sounds. How did you approach that?

“We started by doing what all composers do – having a spotting session with the director. David Gordon Green is directing this movie; he’s a great director. First I picked his brain on where he did and didn’t want music. Then my approach was to use much of the original theme but updated with new techniques and modern sounds. Then we built new music around that, so it’s a combination of those two things.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You worked with your son and godson on this project, like your recent albums…

“That’s right. This is the first time we’ve worked on a score for an existing film. Although the Lost Themes albums were really scores in your mind… so the difference is this is just a score onscreen.”

What’s the working relationship between the three of you like? Do you have set things you each work on?

“We have different talents and different things we can bring to the table. Basically we just started at the beginning of the movie, after having spotted it with the director, and just worked our way through it from the first scene to the last. We did some things that were innovative for us, we used some different sounds – we used a few new synth sounds and Daniel played some bowed guitar.”

How much did the process differ from working on the original 1978 Halloween score? What was the setup like for that?

“I recorded the original score in a warehouse in mid-city LA. I had three days to record it all. My engineer at that time was Dan Wyman, he was a synthesizer teacher at the University of Southern California. He owned the warehouse that he rented out, which was full of old synthesizers – this is way back in the ’70s. These old synthesizers you had to tune up before you could play them, then you had to choose and adjust the sounds from scratch. It was pretty crude compared to today’s work. But basically I just had a piano and all these synths, then I just had at it. Then once I had the theme down and I knew what I was going to do with that, everything else followed.”

How does that compare to today?

“I have my own setup downstairs in my house. It’s pretty much all digital and based around the computer; I use Logic Pro. I’ve got a big library of modern sounds, and we bring in various instruments, so it’s a whole different ball game. The sounds now are far more sophisticated, they’ve got a lot more depth to them. It’s just way easier – you don’t have to tune everything up!”

Are you using mostly plugin synths these days?

“It’s mostly digital but we do use some hardware. We had a couple of old synths for this project – we had an Oberheim on there – but it’s generally new stuff.”

With the original Halloween score, how did you go about working to picture?

“That was a really low budget effort back then, so we weren’t able to do any of that. What I would do is just play some music and I wouldn’t see anything. I basically had four or five pieces of music and then I’d cut those in where I needed them in the movie to make them work. I didn’t score to picture though. Nowadays it’s totally different though, you score right along with the image on the screen. So that’s how we worked this time around – it’s much better!”

Even though you’re perhaps known for vintage sounds, you sound like somebody who embraces modern technology…

“Absolutely, I embrace it fully. The movie business and the music business have both taken this massive turn towards digital, so you have to go with it. There’s no use fighting that. I mean, sure, you can – you can do a 35mm movie and it can look beautiful, but it’s a pain in the ass! I don’t know that it’s worth it. It’s the same with synthesizers, you can scrounge around and find the old synths but I don’t know if it’s worth it.”

You’ve spoken in the past about how you used synths on those early soundtracks out of necessity…

“That’s right. I couldn’t afford to hire an orchestra. Of course, I then started to enjoy doing it that way.”

If you were starting over today do you think you’d still go the same route, now that you’ve got massive libraries of string sounds easily available?

“Oh god, I don’t know man [laughs]. I’ve only lived this one life, who knows what I could do different. But yeah, if you’re young now you’ve got all this opportunity. All this gear to make your own movies and your own soundtracks, and that’s what makes this a great time, creatively.”

"Having no money is no fun! That’s just what I had to work with. People want to romanticise that sometimes, ‘oh, it was only because you had a low budget you could do that’. But that’s not true… it was just a pain in the ass!”

Do you think there’s anything to be said for the idea that having those limitations helped shape who you were, as a filmmaker and musician?

“Yeah, I guess those limitations did have an effect, but I wouldn’t say I liked them. Having no money is no fun! That’s just what I had to work with. People want to romanticise that sometimes, ‘oh, it was only because you had a low budget you could do that’. But that’s not true… it was just a pain in the ass!”

Are you the sort of person who gets attached to specific synthesizers?

“There are certain ones that I love. I absolutely love Oberheims, just the sound of them; all the different variations of Oberheims too. There are certain others too – the Mellotron is still really fun to play with, that has a totally unique sound. Nowadays though, the sampling technology is pretty great. You want a great piano? You can just load one up easily. So I’ve got to say, I do really love the modern sounds.”

We’ve read you talk in previous interviews about not wanting to watch your old films because you spot mistakes. Does that carry over to your music too? How do you feel about going back to old scores and recordings?

“Some of them sound pretty crude to me now. When we did the Anthology release, my son was kind enough to figure out the MIDI for each of those songs, so we could just bring them into the computer and start on them afresh. So I’ve not had to suffer through listening back to too much of my old stuff.”

Going right back, are we correct in thinking it was your father who first introduced you to playing music?

“That’s correct. At a certain age he decided he wanted me to play the violin. That’s what he taught; he was really great at playing it. The only problem was that I had no talent for violin. I moved on after that though; I started on piano, then I taught myself guitar. So I’ve picked up a few instruments here and there.”

At what point did you move on to synthesizers?

“As long as you can play the piano, you can play the synths, so it was just an easy transition. I guess [Wendy Carlos’] Switched-On Bach was something I enjoyed a great deal, and that showed me that there was this way to sound big with just a keyboard. You could approximate horns and strings and everything.”

So you turned to synthesized sounds purely for the purpose of creating scores?

“That’s right. I hadn’t played the synthesizer a whole lot before that. But with those movies, when you needed a little bit more to the score, I realised I could do that myself. I was a fan of those old scores, and I could write music anyway, so the rest of it came pretty easily.”

In 1978 The Sorcerer came out, and that had a soundtrack by Tangerine Dream. God, I went nuts for that, those guys were great.”

Dark Star was your first score, right?

“That’s right. I can’t remember what I used for that though. There was a guy who owned this synth that I borrowed; it was a really crude piece of work, but you know what, it did the trick. I don’t remember the name of it though, you’re talking 40 years ago… Anyway, I graduated upwards on Assault On Precinct 13 and Halloween, and from there I kept working on newer and newer equipment. It’s been really interesting: as the technology matured over the years, I’ve always moved along with it.”

What were your other musical influences for those early soundtracks?

“Rock ‘n’ roll was a really major influence. Riff-driven rock ‘n’ roll has always been a really big deal for me.”

Were you more influenced by that than existing film scores then?

“Yeah, although I was a big fan of Bernard Herrmann, so I tried to emulate a lot of his chords. Then there was starting to be electronic music in movies too. In 1978 The Sorcerer came out, and that had a soundtrack by Tangerine Dream. God, I went nuts for that, those guys were great.”

You worked closely with Alan Howarth for several of your film scores…

“He was an engineer and he owned a lot of equipment. We first worked together on Escape From New York. The editor on that film put me together with Alan, who was doing sound effects and had lots of electronic gear. We worked together for about ten years after that, into the early ’90s.”

How closely did you work with Ennio Morricone on the score for The Thing? Did you give him a lot of guidance on what you wanted there?

“On the main title music I did, yeah. I couldn’t speak Italian and he couldn’t speak English, so there was a language barrier, but right from the beginning he had some musical sketches he played for me and I just said, what I’d like you to do is something electronic, but fewer notes. So that’s how we developed the main titles. But he did some beautiful, beautiful string music for it too.”

You play his main theme during your live sets?

“That’s right, we’ve been playing that most of the time on tour.”

Has it been much of a challenge working out how to take your film compositions out live?

“No, well, at least it wasn’t the music so much. There were a couple of things that were tough. For one, we didn’t really know what we were going to do. People kept asking us, ‘What is this?’. We said we were going to go out and play some movie music, but nobody really got what that was about at first. I got a great band together though; not only my kids but we’ve also got Tenacious D’s rhythm section playing with us. Those guys are unbelievable. So once that came together it started to fall into place. I had to get over my fear of the audience too. Once I got past that though, it was really fun – just a blast.”

Did you have any experience of playing live with a band before that?

“Sure but only from when I was really young. I used to play in a cover band, but that’s a long time ago. This though… I was walking out in front of a really big audience. But once I got over being a little nervous, it worked out great.”

What are you actually playing live? Do you take a specific synth onstage?

“My son Cody and I are playing synthesizer sounds, but we’re working off of computer programs. All the sounds are stacked in the computer, and I’m just playing a MIDI keyboard that is basically just hooked up to all these sounds.”

Between your albums and live shows, you’ve been more focused on music than films over the past decade. Do you think you might swing back towards cinema at some point?

“Yeah, I might. But it’s a lot more fun to do the music right now. I’m involved in some movie and TV things, so we’ll see. But I’m more interested in having a good time at this point in my life!”

5 essential Carpenter soundtracks

Halloween (1978)

The score to Carpenter’s original horror masterpiece was composed and recorded in a warehouse in central LA. The main piano theme – a simple pattern in 5/4 time – has become one of the most recognisable motifs in cinematic history.

Escape From New York (1981)

The soundtrack to Carpenter’s early-’80s dystopian sci-fi thriller saw the director team up with regular collaborator Alan Howarth for the first time. It was also one of the first times Carpenter composed a score while watching footage of the film itself.

The Thing (1982)

The score for The Thing was actually composed by Italian master Ennio Morricone. However, despite a language barrier hindering communication, Carpenter’s influence can be plainly heard in the drawn-out, minimal synths of the main theme.

In The Mouth Of Madness (1994)

This mid-’90s addition to Carpenter’s ‘Apocalypse Trilogy’ might not be one of his best-known films, but its main theme is a highlight of his live sets. Its distorted, driving guitar riffs show the influence that rock music has had, alongside the more obvious synth touchstones.

Lost Themes I & II (2015/2016)

Recorded with his son Cody and godson Daniel, Carpenter’s two artist albums might not be soundtracking any specific films, but the director still envisions both as scores for films ‘in your mind’.

I'm the Managing Editor of Music Technology at MusicRadar and former Editor-in-Chief of Future Music, Computer Music and Electronic Musician. I've been messing around with music tech in various forms for over two decades. I've also spent the last 10 years forgetting how to play guitar. Find me in the chillout room at raves complaining that it's past my bedtime.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track