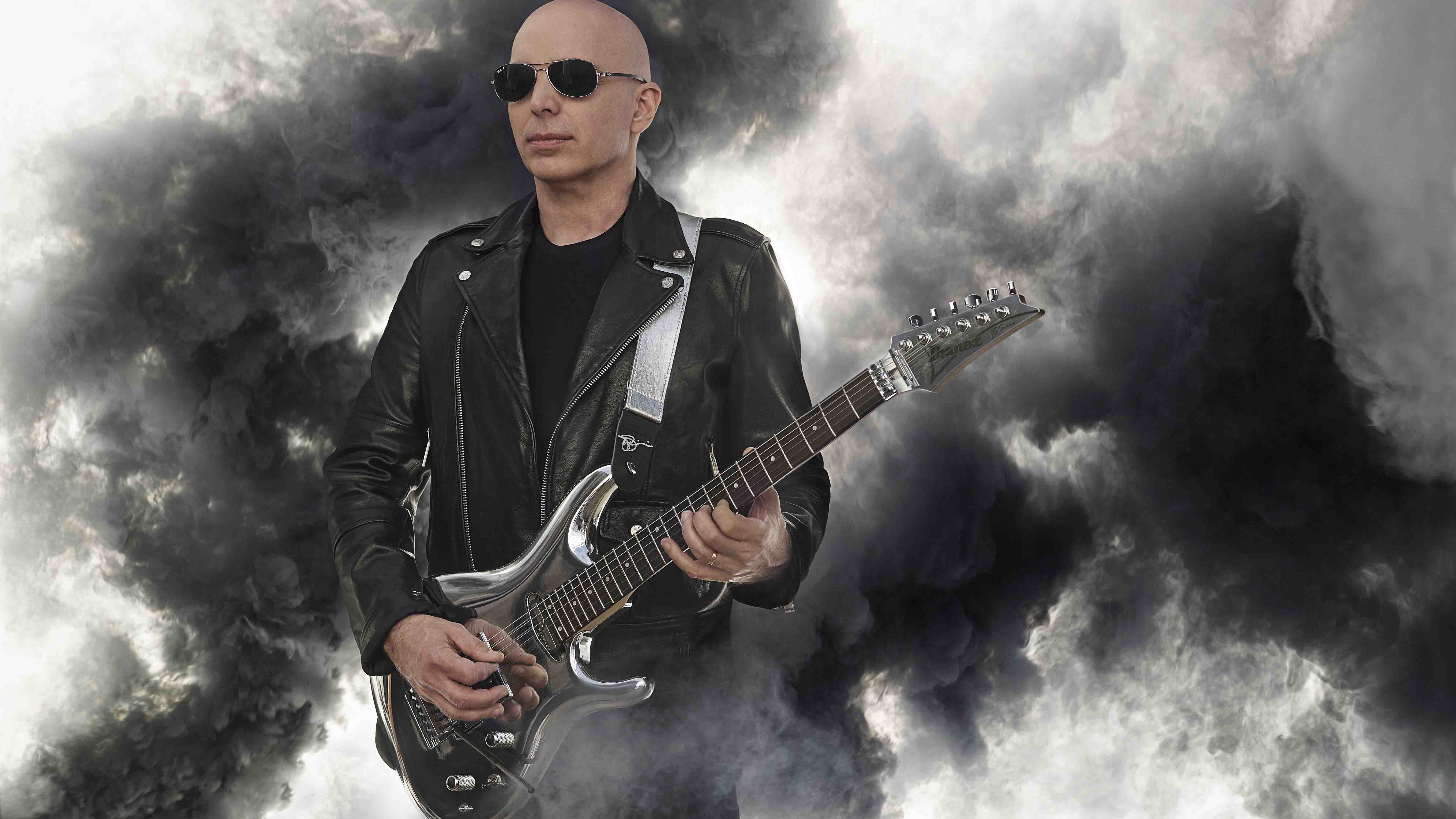

Joe Satriani: "I just wanted to raise my bar – I just wanted it to be higher on every level"

Satch tells us how went down the rabbit-hole of his imagination for new album The Elephants Of Mars

Few players have done more to deepen our understanding of the guitar and its musical potential than Joe Satriani. Even if the amiable Long Islander chose not to pursue a recording career he would still have done more than most to shape the way we think about and play the instrument. Satch’s alumni – Vai, Hammett, Skolnick, LaLonde et al – would have seen to that.

But he did, and Satriani’s latest studio album, The Elephants Of Mars, is a welcome reminder that Satriani’s understanding of the guitar is evolving all the time, and that how we think about and play it is far from a settled matter.

We live in a world of democratised virtuosity but The Elephants Of Mars is something else entirely. Audacious in scope and execution, Satriani and his collaborators made full use of the pandemic’s dead air and empty calendar to write something abutting the realms of the impossible.

I am so fortunate that I can spend all day writing music, recording, playing guitar, painting, imagining the craziest things and just transferring what’s inside and making it palpable so people can hear it and see it

As Satriani explains over Zoom, it’s not the first time he has attempted the possible. Back when cutting seminal instrumental rock albums with John Cuniberti there were moments – notably recording The Snake – when his imagination outpaced the physical limitations of artist and recording equipment alike. The Elephants Of Mars is of a different era. It is an album on which Satriani never used a regular guitar amp, running his Ibanez JS Series signature guitars through a SansAmp plugin exclusively.

But there’s something similar in how Satriani stitches together his arrangements of disparate styles and sets them alight with carefully chosen moments of technical ecstasy. Sometimes his technique is an emulsifier of what might be otherwise musically incongruous, resolving a lick with some harmonically off-menu sleight of hand, or with a peal of reality fracturing whammy bar noise – of which there is plenty.

On occasion, he’ll lean on effects as a bridge between two vibes. To complement the microtonal groove of Sahara he reached for a Dunlop Hendrix ’69 Psych Series Octavio Fuzz in the solo. The TC Electronic Sub ’N’ Up and Electro-Harmonix Micro Q-Tron augment the title track, and there’s always his Vox BBW wah pedal on-hand to lend a liquid, vocal quality to his legato lead playing.

I write for everybody and my hope is that the music can become the soundtrack to people’s lives, that it stands the test of time

There’s something avant-garde about all this, in the limitless fusion of musical ideas suspended in orbit around what is at its core an instrumental rock style. There is the sci-fi through line in both his visual art and music. But ultimately The Elephants Of Mars sounds like it does because Satriani gets a kick out of all this, from staking out new horizons for guitar – and he hopes that you do, too, whether you play or not.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I write for everybody and my hope is that the music can become the soundtrack to people’s lives, that it stands the test of time” he says. “I want people to listen to it over and over again.” He pauses. “And I love guitar! So I kind of manage the two things together.”

Does your visual art inform your music? Because there is a Joe Satriani aesthetic – the sci-fi sensibility in your painting, in the music. There must be a connection.

“Yeah, well I am definitely a spacey kid, I guess! [Laughs] I am so fortunate that I can spend all day writing music, recording, playing guitar, painting, imagining the craziest things and just transferring what’s inside and making it palpable so people can hear it and see it.

“I just love that. I always have. I grew up in a family of seven. I was the youngest kid. And there were artists and musicians in the family. Lots of music all the time. My parents listened to jazz and classical, and more older siblings went through rock ’n’ roll in the ‘60s and early ‘70s, and I was the recipient of all of it.

Guitar is the easiest instrument for me to play, and I should reinterpret that by saying that it’s the instrument that gives me the least resistance!

“I never really picked one thing; I just received all of it and said, ‘I like all of this. All of this is a part of me.’ So, when I put together an album, I feel like I have got all these resources that I have collected over my whole life, and it helps me interpret these feelings I have.

“Guitar is the easiest instrument for me to play, and I should reinterpret that by saying that it’s the instrument that gives me the least resistance! [Laughs] ‘Cos I would love to be able to play piano, and saxophone, drums and all that, but those instruments give me the ultimate resistance! [Laughs] But luckily the guitar allows me to go further so I can get these ideas out.”

Do you have a theme when you are writing? When we speak to some of your peers, particularly in the instrumental space, like Paul Gilbert, he will speak about how he likes to write his melodies to a lyric. Or is it a little bit more of a visual thing, like when you were talking about Shapeshifting, and you had these far out visions like on Ali Farka, Dick Dale, An Alien And Me.

“Oh yeah! On Shapeshifting, Ali Farka, Dick Dale and the alien and that whole thing, that’s like a daydream – a great film about how we are all together and we are at this party in North Africa an are jamming, and it is an absurd idea but I just thought it was a really fun daydream to think about. Wouldn’t that be great if that someday that would happen? What would we play? How would we hand off parts to each other?

Joe Satriani offers a track-by-track guide to his 2020 album Shapeshifting

“I was determined to write in as many different styles as naturally came to me, and not to worry about making the album a metal album, a blues album, an EDM record, whatever. I wasn’t going to force my compositions into a stylistic tube.”

“And then sometimes there are other reflections, like you said, Nineteen Eighty, that was really about me being so excited when Van Halen came on the scene, and how I was so invigorated at the fact that Eddie put it all together, and represented what I was really hoping would happen with the electric guitar. Because it was getting quite weird, I thought.

“As the ‘70s were wearing on, my perspective, being a young rocker and then working in a disco band and being disillusioned by it, and then starting to travel the world in search of something, then Van Halen shows up and it’s like, ‘Yeah!’ Like there are people who are adrift like me and they wanna rock, and they wanna innovate. And the Van Halen brothers were just so musical. They transcend their age in a way.”

But this one came out of quite different circumstances...

“With this record, the environment was so different, and it is real important to note that, when I finished Shapeshifting, I really did want to move on. I thought, ‘Okay, I’ve done two records in a row where it was really kind of classic rock, a modern approach but I was really dipping a lot into classic production; being in a classic studio, being with classic engineers, having guys in the band with me recording live with rock musicians.’

“So, this time I thought, ‘Well, we are, we are all remote, and I don’t feel so pressured by the clock on the wall and the date on the calendar. I don’t have to deliver this any time soon, and I can take 14 days to play one rhythm part if that’s what I want, y’know! [Laughs]

I just wanted to raise my bar, y’know, the standard for Satriani records, I just wanted it to be higher on every level

“And suddenly I realised, I can really dream up the craziest record. What should I do? First and foremost, I gotta get better. I wanted to write better songs. I wanted to arrange songs in a higher level than I have ever done before. I want to play better, and I want the album to sound better.

“I just wanted to raise my bar, y’know, the standard for Satriani records, I just wanted it to be higher on every level. And I thought now was the time because I have got the time. That’s how the whole thing got started and then I didn’t know where it was going to go! Which songs would wind up on the album, but you never do know that until it is done.”

There’s something of the avant-gardist in you. Listening to the new one was a great excuse to dig out your debut EP. You recently poo-pooed that a little bit but it holds up, and that sort of iconoclasm is still part of your sound. Some of the sounds on this record are insane.

“Yeah, well, I am I big fan of Kurt Vonnegut. Ha! I read all his books. The idea of the absurd is really important when you are creating art because you have to be able to look at yourself and realise that this thing that you are creating is the most precious thing ever, and at the exact same time, it is completely worthless and pointless. I mean, that’s the Kurt Vonnegut view; life is precious but it doesn’t matter.”

The idea of the absurd is really important when you are creating art because you have to be able to look at yourself and realise that this thing that you are creating is the most precious thing ever, and at the exact same time, it is completely worthless and pointless

So it goes…

“But once you get free of thinking, ‘Oh this is so precious, this album of mine,’ then you realise, ‘Oh, what am I protecting here? Is it my feelings? The perception of how people see me?’ All of these things are destructive in that they hold the artist back. On a practical level, recording in a room with a bunch of musicians, spending thousands of dollars an hour, knowing you have only got a week or two to record all of the songs, that’s a pressure that makes you pull the reins in, and compromise on an hourly basis.

“When you finish the record and go, ‘I’m so happy I have the ability to make an album. One of these days I’ll have time to do it the way I want to do it.’ And that kinda goes on and the end of your career comes and you go, ‘How come that never came!? How come I never got to do it?’ So, last year I thought this was the time, ‘You have no excuse about performance now.’ Because there’s nobody in the room. You’re not going to get embarrassed if you make a mistake.”

And that is very freeing...

“You’re not going to get shy and want to cry when you are playing because there is no one to look at you. You can do what you want. You can be as happy as you want or you can be as sad as you want. And you can try to play things you can’t play, and it’s okay ‘cos you don’t have to put it on the record. But you can try everything and take as much time as you want, so that was a real gift that I gave myself.

I routinely humiliate myself by putting on a live DVD of Tommy Emmanuel, and I go, ‘I will never achieve that!’

“I should have done it before but I never had the economy, the budget to be able to do that kind of thing. Records have to get done, basically [Laughs]. Once I got into that and I started sending the songs out to the other musicians I told them the same thing, which is, ‘I know your situation is not exactly like mine but, if you want to take two weeks to do this one part, you go right ahead because we don’t have a delivery date. Wait until you’ve had fun with it and you have decided you really want to do something interesting with it. Then send it back and we’ll react to it as a group.’

“So I was getting Rai’s keyboard stuff from Australia. Ned [Evett] was in Galveston, Texas, when he did the voiceover for us. And the other guys are in the general LA area but travelling. Kenny Aronoff is travelling around the world all the time. So it was very interesting putting the record together that way and giving all of us that carte blanche to just relax and apply ourselves more than we would if we had that tight three-hour session time.”

And those performances are wonderful. Kenny and Brian, what a rhythm section… It’s a Joe Satriani record, your name is above the door but everyone adds something great to this. Pumpin' is a great track, so very ‘90s New York. Brian is having so much fun pulling it forward and you’re kind of sitting at the back of the pocket. There is a great conversation in that groove.

“Yeah, that is one of those songs where I didn’t know if anyone would want to play it. You got it right in terms of the vibe, that sort of early ‘90s vibe – funky, techno, groovy, whatever – and I was putting my guitar in the backbeat, sitting on top of it. It has got these three really weird sections that almost don’t go together, but it was all programmed, and so, when I sent it to Brian, I said, ‘Can you actually play something like this and make it sound comfortable, or is it too automated?’

“The drum loops that I had going were totally inhuman, so Kenny’s job was to sort of make it human-sounding, y’know, and so, it’s funny, when we sent it off, when we finally had a really good version of it, we sent it off to Rai and we had no idea [what to expect]. I never told Rai what to do and what he played I just thought was so perfect.

“It was just so funny and yet… He has a way of just playing the deepest musical lines, even though it can have an uplifting and bright kinda attitude, which is really part of his personality. He is just a fantastic human.

“But how the song winds up is just really funny. That ending has a lot to do with what Kenny and I were doing with Doug Pinnick in ’19, when we were touring with the Experience Hendrix Tour. It was a lot of that groovy Mitch Mitchell late ‘60s rock/swing kinda thing going on.”

Talking about inhuman, let’s talk about the title track. You really push the envelope of the unorthodox there, where it’s almost anti-music in places. One minute and 50 seconds in there is one of the coolest guitar sounds ever.

“First of all, thank you. It’s a great example of how collaboration is so important to complete a new level, an artistic level that you are trying to reach. You have to really open up to ideas. The Elephants Of Mars got its start with this shorter piece of music that I had.

“It had the elephant sounds, and it had that guitar solo on it. However, that guitar solo was not in a breakdown section. It was a super-clear, bluesy sounding bit of guitar, not too many notes. It was really drifty and really ethereal sounding.

“When Eric and I were working on the song, Eric had this idea of taking that guitar solo and just playing different chords underneath it, so when he sent it back to me it totally blew my mind because the way that he harmonised it was completely the opposite to my sort of Nine Inch Nails meets Mark Knopfler version on the demo! [Laughs]

I wanted to use the symmetrical scale but I also wanted to somehow throw in some rock guitar – like if Chuck Berry had known music theory and applied his brilliance to jamming on a symmetrical scale using a Sustainiac and a whammy bar, that’s what it would sound like

“Because, originally it was [hums guitar part]… Y’know? It was really different. The key change was there but he just played some extra chords and then delivered it right back to where I had delivered it, which was at the main Elephant theme.

“When you compose with other people and you give them room and license to try stuff, you hope that you are going to get surprised like that. And then once I heard that, and we had this idea of doing a long solo at the end, I knew what I wanted to do based on that.

“I wanted to use the symmetrical scale but I also wanted to somehow throw in some rock guitar – like if Chuck Berry had known music theory and applied his brilliance to jamming on a symmetrical scale using a Sustainiac and a whammy bar, that’s what it would sound like. [Laughs]”

This record has a feel for the spectacular but also the small moments. Are you very conscious of those dynamics when writing and sequencing the record?

“Oh yeah. I’ve always loved having the studio as the place to do the last bit of writing, and being able to really explain the meaning of the song through the process of not only instrumentation and editing but the mixing. In the old days we had to take out the razor blades and cut tape, and it was pretty dangerous and very destructive.

“I remember there was a song on Not Of This Earth called The Snake, and as I explained it to John Cuniberti – I had written it on a piece of paper – I had no idea of how I was going to record it because I can’t play it humanly. It’s impossible to play the whole way through.

“So I said, ‘Here’s this section, aluminum foil on the strings, pick scraping on this section, whammy bar section, and there’s a blues section…’ And he’s looking at me, going, ‘Okay, I’m just going to record each section separately and then we’ll cut the tape together, and we won’t know if it is going to work until we are done.’ So, I thought, ‘Okay, I’ll try it.’

“So, we recorded each section in that whole thing while the drum machine is going, and then we waited, we took out the razor blade and the tape and we cut the whole thing together, the two-inch tape. You do that once and that’s just about it. You make a mistake and it is never quite the same. It’s very risky, especially when you can only afford one reel of tape, or two, for a whole album! [Laughs] I think it was 150 dollars a reel and that was all I could spend at the time.

I am just a little kid in the candy store when it comes to music, and I really don’t know until the end if it is going to work

“But when we finally taped that whole solo section together and I sat back and I listened to this incongruous litany of sections together, originally going back to this RnB song, I thought, ‘That’s the greatest thing I’ve ever heard in my life.’ It’s so funny, and yet it is so heavy, and it allowed me to innovate on the guitar and give people a fun song but at the same time show them that you can do this with an electric guitar that maybe you hadn’t thought of before.

“Once you have that experience you go, ‘Ooh, wow! I wanna do that a lot!’ And with digital recording, you can do it at home because non-destructive editing is like sitting down with manuscript paper. You can keep changing it and it’s non-destructive. It’s great. In a way, it harkens back to pre-recording days, when artists felt free to arrange and rearrange sections at will.”

We have stumbled on the working title for the next album – ‘incongruous litany of sections’. You must have established an internal logic by now that you instinctively know what works, that the crazy ideas can be put into the composition?

“[Laughs] I like to hear you say that but no, I have to say, honestly, I really don’t. I am just a little kid in the candy store when it comes to music, and I really don’t know until the end if it is going to work. And we really don’t know, as a group, and as a production team, if it’s really going to work. Now, of course, it will work for other people, but does it work for yourself? When you are making an album, you are really making it for yourself and you are the harshest critic ever. However, you have no idea how it is going to be received.

When you are making an album, you are really making it for yourself and you are the harshest critic ever

“I always remember what Glyn Johns said to me many years ago. He goes, ‘It’s not your job to decide what people will like and what people will not like. It is your job to play your guitar.’ And it clears all the anxiety away. You can’t force people to like it and you can’t force them to listen to this specific part that you think is so great and innovative. They are just going to hear it the way they want to hear it. So, when you’re done, you smile and say you did your best, ‘I’m proud of my work,’ and move on.”

You do force us to listen to it in a sense because a track like Dance Of The Spores makes you think, ‘What did I just hear?’ And you have to revisit it as soon as the record is finished to hear what’s going on. It’s almost like something Susumu Hirasawa would write, very playful.

“Oh thank you. I was having this idea that all the world’s troubles are always on our mind, 24/7 news cycle, climate change, the pandemic, politics, all this stuff, that on a smaller, almost microscopic level, there is life and they are having the time of their lives. The spores, they don’t care about whatever is happening to humans, and they’re out in space, sitting pretty and having a party. And I thought, ‘I should write about that.’

“I had this vision in my head of these spores having this beautiful sort of circus party in the middle of the forest during the night, and what it would sound like. The funny part about it is that it’s a combination of dark and menacing and really light and romantic sounding.

“Then there is that breakdown section that I had written and recorded with piano and guitar, and as a joke, just to make my producer angry, I added pizzicato strings, and that’s because over the years he has always complained that I use that sound too much. And he always ends up trying to eliminate it from the final mixes.

“This time, I turned it up really loud when I sent him the demo, and I was waiting for him to call me back to say, ‘Damn you, Satriani! Those pizzicatos!’ But he didn’t. Days go by and I am wondering why that joke didn’t work. And so then he sends me his version of it, and he has taken that whole section there, and kept my piano and guitar, and he added the Bulgarian women’s orchestra and the Mexican horn band, and all the other fantasy stuff that I couldn’t even fathom! And it was his way of punking me back.

“But of course once I heard it I thought, ‘That is magical. That’s so magical!’ That inside joke turned into something really special and it helped balance the song out and support the title and the meaning of the song.”

We have spoken before about North African influences on your writing, and it it sounds like that’s what you are referencing on Sahara, playing around with those microtonal bends and that mood. Was that the influence there, and maybe players such as Mdou Moctar?

“Yes, yeah, that’s what I was thinking. The story and the lyrics that I had written for Rai to sing were all about a guy who was lost in an urban environment and he feels like he is in a spiritual desert and slo he can’t find anybody. In the middle of the night in New York City there’s just nobody. There’s no life, no anything.

“I was trying to represent that feeling of being lost, and I’m not really sure why I wound up using those 12-string electric guitars but I can tell you that once the song went from going from being a vocal song to an instrumental, and I went to play a melody on top of it, I realised it was a minefield for a guitar player. Because, as you said, there are these microtonal bends and when you try to get a melody to be in tune – in a western sense – with these microtonal bends, it’s like, ‘Woah!’

“I had to come up with a melody that had a lot of upbeats in it, and syncopation to represent the anxiety that the singer has when he is singing these verses. And I also had to dodge landing on the root when these 12-strings were bending almost to a flat 9. You know what I mean? Real guitar nerd stuff! That took a while.

“It was like walking through a funny little microtonal minefield but it wound up creating this sort of sexy rhythmic vibe that I really loved, and then I was able to keep the melody in the breakdown section that was originally for Rai to be repeating like a mantra.

Sahara was like walking through a funny little microtonal minefield but it wound up creating this sort of sexy rhythmic vibe that I really loved

“He gets really quiet at one point and says, ‘Everything is going to be all right / Everything is going to be okay / Everything is going to be all right, like it was before’ and he keeps repeating that. When I was doing the instrumental version, I got to that and I went, ‘I’m just going to play that, just because that mantra is so important to show how lost this guy is.’ And he’s hanging onto his sanity by a thread, repeating this thing over and over again.

“To my surprise, Eric added a lot of eastern influences, from North Africa to India, and fleshed it out, adding a lot of interesting textures around that clean guitar, before my total Hendrix octave guitar takes over! [Laughs]”

That is one of the songs that we do listen to as a guitar player, because it makes us tense. You are Mr Intonation, one of the physical laws of Joe Satriani is that the intonation will be on-point, and you would have worried about that tuning a lot.

“I’ve got a big Korg studio tuner, and they’re pretty close. Y’know, what I did with that, and it’s interesting you mention it, I realised that my performance on the 12-string was a little crazier on the beginning than it was in the second half, the second verses that come after the solo section, and then I also thought, well, it’s the beginning of the song, and I kept referring back to the lyrics, and the lyrics were really scary in the beginning.

“I mean, the guy’s really out of sorts. But after the first chorus and the breakdown, and the solo section, he is beginning to see how he is going to be able to move forward. But he is arguing. The thing is – I know this is really weird. [Laughs] In the song he meets this female deity who says, ‘Love is the answer’ and he hates the answer; it’s not what he wanted to hear. Because he can’t understand it.

“How can love be the answer to this complete emptiness that he’s feeling? So, he starts screaming it, ‘Love is the answer!’ But he doesn’t believe it, so you can hear it in the sound of his voice. It’s like a John Lennon kind of a song, where he is saying something with words but the voice is telling you something else that’s the opposite of the words, right?

“This made it difficult for me to sell the song to the band because it was too complex, and maybe my lyrics weren’t very good. But I kept going back to them and saying, ‘Okay, that’s why the guitar solo is so freaky.’

“It’s like Hendrix freaking out thing, but that melody comes back in, and when the verse comes back in, suddenly there’s less tension, less micro-tonal tension there, and that was intentional, because he’s getting stronger. He’s angry now. And I couldn’t use the vocal melody that love is the answer. It just didn’t work as an instrumental melody, so I had to write a new melody to go with the end.

“Then Eric added some descending chords underneath those two melodies that I had and that completed the whole thing. But yeah, the microtonal thing, I’m glad you brought that up because that was a thing that, as a musician, I really had to scratch my head and think about how I was going to deal with it.”

That motif comes over a little like a sedative. It draws you in. Though, again, from a musician's POV it sounds like it was the one great idea at the beginning that soon became a Schumann situation where that was the note that would drive you mad.

“[Laughs] We had a mix where we took it, because we all noticed it right away, but what we decided was that, when it was there, it added this vibe that was so essential to get you into the mood of the song, and to make you feel like, at the end of the song, you really went through something, like it was cathartic. So yeah, I’m glad you pointed that out.”

Finally, tell us a bit about The Doors Of Perception. We sometimes do think of you as a pure electric artist – there is that current and voltage to your performances. This acoustic track though is fascinating, it has a Ravi Shankar/Jonny Greenwood soundtrack vibe, and it has a very different energy.

“I think if you were to put all my acoustic songs together I think you would hear a very different approach and it is because I routinely humiliate myself by putting on a live DVD of Tommy Emmanuel, and I go, ‘I will never achieve that!’ [Laughs] But thank God for Tommy for doing that. And Adrian Legg, same thing, and we have toured together, and it was just like, ‘Oh God, these people are just connected to that instrument in a special way.’

“But I love the instrument, and it is on a lot of songs in my catalogue. You’d be really surprised. It might be on If I Could Fly with six and 12-string acoustics, or on this record 22 Memory Lane and as you said The Doors Of Perception. I love open tunings, and do a lot of stuff on acoustic guitars and then see where it is gonna work.

“That particular track has a got a good balance of my [Ibanez] JSA which is very modern and has full [fretboard] access and the intonation is a little better than the Martin. But the Martin, of course, is a Martin, so you put the two of them together and you multilayer them and you get something really special out of them.

“I had this idea that the more that you open the doors of perceiving the world you let good and bad in; you have to be ready for some scary things, and wonderful things to, and that’s why, when the song ends, it ends with a sort of strange, eerie questioning riff. It doesn’t end all pleasant! [Laughs]”

- Joe Satriani’s new album “The Elephants of Mars” is released worldwide by earMusic on April 8th. Info: www.ear-music.net and www.satriani.com

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.