Jeff Beck: "I was pretty down at the time, I'd lost my girl, Hendrix had come and smeared everybody across the floor… I’d fallen out with the Yardbirds"

Classic interview: More than 55 years on from his ousting from The Yardbirds, we revisit this classic interview where Beck looked back on an incredible story

The music world is paying tribute to legendary guitarist Jeff Beck, who has died, aged 78.

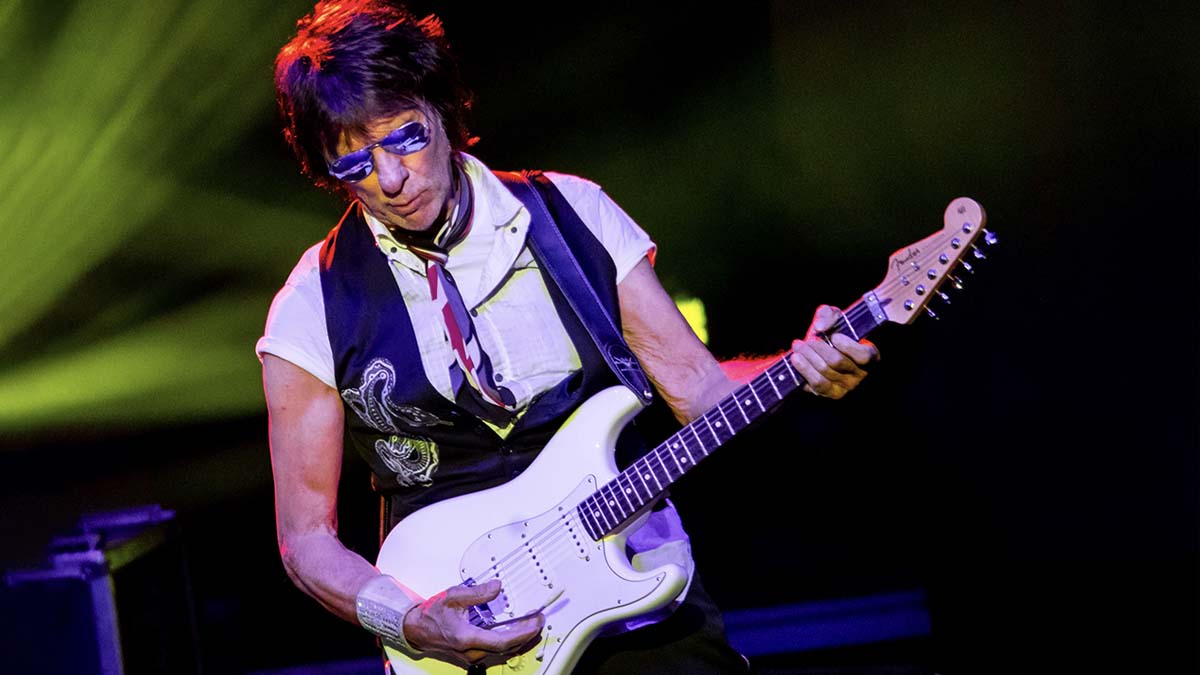

In 2016 Total Guitar interviewed iconic guitar maestro Jeff Beck for a cover feature to talk about his then-new album Loud Hailer, and a retrospective photography collection, BECK01, prompting a look back at his roots and early days with the hugely influential Jeff Beck Band.

Classic Interview: From playing blues with the Yardbirds in the 60s, Jeff Beck has taken his beloved Fender Strat into the worlds of fusion and jazz-rock, rockabilly, electronica, and now he’s plunged into straight-ahead hard rock by teaming up with Rosie Bones and Carmen Vandenberg from the band Bones UK.

Loud Hailer was written by the trio at Beck’s house, a process aided by several crates of Prosecco, and is released alongside BECK01 - a book of photographs chronicling both the guitarist’s long career and his lifelong love of hot rods. Preparing [when we spoke] to mark 50 years in music with a huge gig at LA’s Hollywood Bowl, Beck’s engine shows no signs of slowing down.

What was it about Carmen Vandenberg as a guitar player that made you want to work with her?

“First of all, I couldn’t believe that a young 22- or 23-year-old girl would be in love with Buddy Guy, or even know about him. When she said Albert Collins that was it, because I think he’s the coolest.

“She goes, ‘I’ve got a band with a girl called Rosie and if you want to hear us, we’re playing at this place.’ So we hot-footed it up there not knowing what to expect and there they were just giving it large. I thought, ‘This is great, maybe we should ask them down, go outside of their style, try to challenge them to do something else.’

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“My job was to instigate the proceedings. It was joyous watching them get stuck in - I just had to put the idea on the table and they were all over it with a freshness that’s so lacking nowadays.”

Were you and Carmen coming from the same place musically speaking?

“The big joiner was the blues, and the fact that she could really play made me think, ‘Wow, this is incredible, maybe this is the right choice for me.’ And to have Rosie as well - I hadn’t envisaged a time when somebody would sit down in my house and literally write lyrics as I was coming up with the ideas.

“We made the demos and they weren’t great sound-wise, but the content was there. You could see what was going to unfold with very little effort. Then the third thing that cemented it was Filippo [Cimatti], who produced it. To have those three people of one accord joining up with me it made a pretty slick outfit."

"Not having any giant hits - it makes it a lot easier to just jump into another genre"

Any young guitarist might feel intimidated at the prospect of playing with you. Was Carmen nervous?

“She probably was, but I tried to instil confidence so I was playing tutor as well. It wasn’t any high pressure thing, ‘You’ve got to learn this,’ but she treated it as though it was. She’d go on YouTube and check me out.

“The last six months hasn’t just been doing the album, she’s been learning all the stuff and following my career, so there’s been just about enough time to get comfortable and I’m confident that she’s going to deliver.”

You obviously have a reputation for musical reinvention - how many times do you think you can do it?

“I think it’s good to do that and it’s been easy, because if you have a massive hit, where are you going to go? You’ll make the worst step ever and slip over, but not having any big hits - and I mean giant hits - it makes it a lot easier to just jump into another genre because you’re not cheating somebody out of something they like.

“I’m an experimenter. It’s rich because every album I’ve done, except for a couple of techno-y records, are different. Really you’ve got to hand it to the Fender Strat, because there are songs in [that guitar]. It’s a tool of great inspiration and torture at the same time because it’s forever sitting there challenging you to find something else in it, but it is there if you really search.

“It does respond to touch and the tonal variation is unlimited really, especially with the whammy bar. I have it set up so it becomes almost like a pedal steel.”

"A Les Paul feels like a guitar and I play differently on that and I sound too much like someone else"

You’ve played other guitars over the years, are you ever tempted to use a Les Paul or a Telecaster again?

“My Strat is another arm, it’s part of me. It doesn’t feel like a guitar at all. It’s an implement which is my voice. A Les Paul feels like a guitar and I play differently on that and I sound too much like someone else. With the Strat, instantly it becomes mine so that’s why I’ve welded myself to that. Or it’s welded itself to me, one or the other.”

The 10 best Stratocasters: our pick of the best Strat guitars

You recently said that Loud Hailer was you trying to get away from music that only pleased guitar nerds and guitar magazines…

“That came out as a little bit of slur on [guitar magazines], it was never intended to be that. I just didn’t want to be a central figure in muso-land. I want to be doing more than being on the cover of Guitar World magazine.

“That whole scenario of reciting a series of instrumentals, I’ve done it - I’ve done it with an orchestra, I’ve done it with fusion, and it’s okay but it’s so wearing. It’s very difficult to be entertaining. That was okay in the day, especially with Jan Hammer [Mahavishnu Orchestra keyboard and synth maestro that Beck collaborated with in 70s and 80s], because there was gymnastics that were beyond belief - but there is no Jan Hammer anymore - he doesn’t play live shows, he’s folded the tent, gone into the studio.

“I’d love him to come out to the Hollywood Bowl, maybe give him a little tweak in this article - ‘Jan! How can you not be there when you’re such a major part of my career?’ But I think he has a fear of travelling… or a loathing for airports [Jan does indeed make it to the Hollywood Bowl gig as you can see in the video below].

“I also have a loathing for airports - it’s only by the grit of my teeth I get through them. But I didn’t want to start becoming elite and above [guitar magazines] - they’ve been great to me. I didn’t want to be in the middle of a fusion confusion, I wanted to be me again. The real me is on this record, more of the real me musically.”

That makes sense, after all your fan base is a very broad church…

“Yeah, but because the guitar is what it is - there are magazines that just focus on fuzzboxes and string gauges and stuff like that - the average girl in the street wouldn’t even know what they’re talking about. This album will enable a much broader scope to be drawn in to who I am. Who knows, it might work in my favour!”

Your new book, BECK01, is an interesting idea - how did that come about?

“Genesis Publications had already done Jimmy Page [2010’s Jimmy Page On Jimmy Page], so I supposed I was in their sights. I didn’t want to do it at all and they said, ‘But you can choose what photos go in there.’

“So I agreed a bit reluctantly. Because my autobiography was delayed and I thought this would be a missed opportunity to have an album and a tour and not to have something there, so I agreed, at least that photographic album will be out.

“I’ve seen it enough times to start worrying about what’s in there! Hopefully somebody will get some enjoyment out of it, there are some rare pictures in there.”

Was it an emotional process going through all your photos?

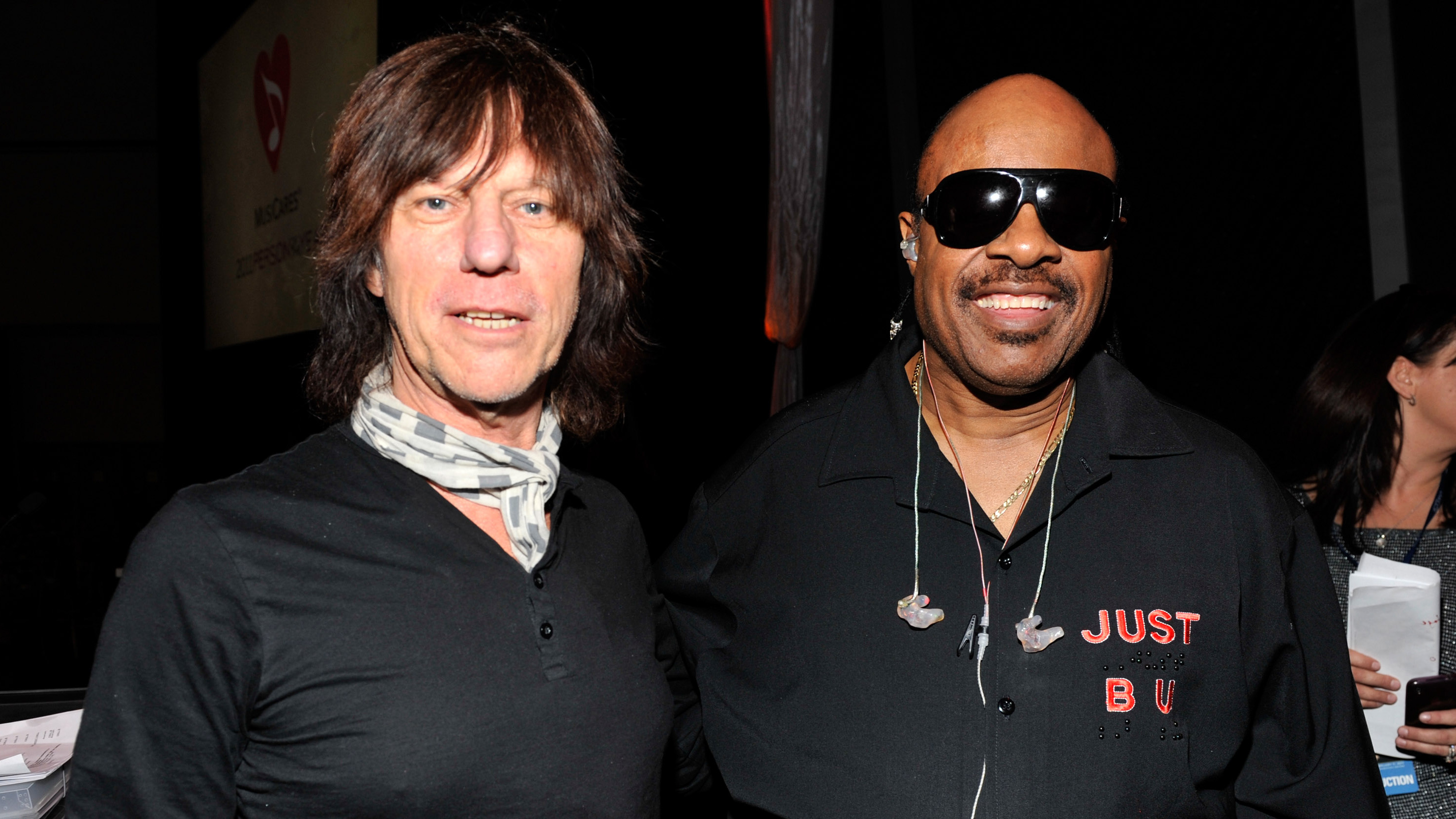

“Yeah. The first day we’d look at a picture and talk about it for 20 minutes. ‘We’ll never get there! Come on! What about this one?’ There were the obvious ones of me and Stevie [Wonder] in Electric Ladyland, and I’ve got a rare shot of me in Motown.

“There are only two in existence, faded Polaroids of me sitting at the desk in Motown when I was there in ’70/71. It was right before they folded and went west, and I think there is one with [producer] Mickie Most posing outside Hitsville [USA - Motown’s original headquarters in Detroit].

“What a time - 10 days of racism and abuse! They didn’t like me and Cozy [Powell, Beck’s drummer at the time] until we started playing. ‘Hey Whitey! What have you got?’ Cozy comes out with his double bass drums and it’s deafening and they’re not used to that. But after a few days they really took to us.

“We were trying to super-charge what Motown were offering. They had these very tasteful, beautifully played pop singles, we came along and put metal to it - Metal Motown. The funniest thing was one of the tape ops said, on a coffee break, ‘You guys came here for the Motown sound?’ ‘Yeah, man!’ ‘It just went straight out the door!’ because Cozy moved the drum kit!

“I said, ‘What are you doing, Cozy?’ He said, ‘Well, I can’t play that kit. If you want, I’ll play badly on that kit or really well on my kit.’ I went, ‘Okay’. He didn’t realise that was the Holy Grail of that studio. They were tuned for the room, how could he not use that kit played by Benny Benjamin, Pistol Allen? But that’s just the way he was.”

What about taking on the burden of writing the material?

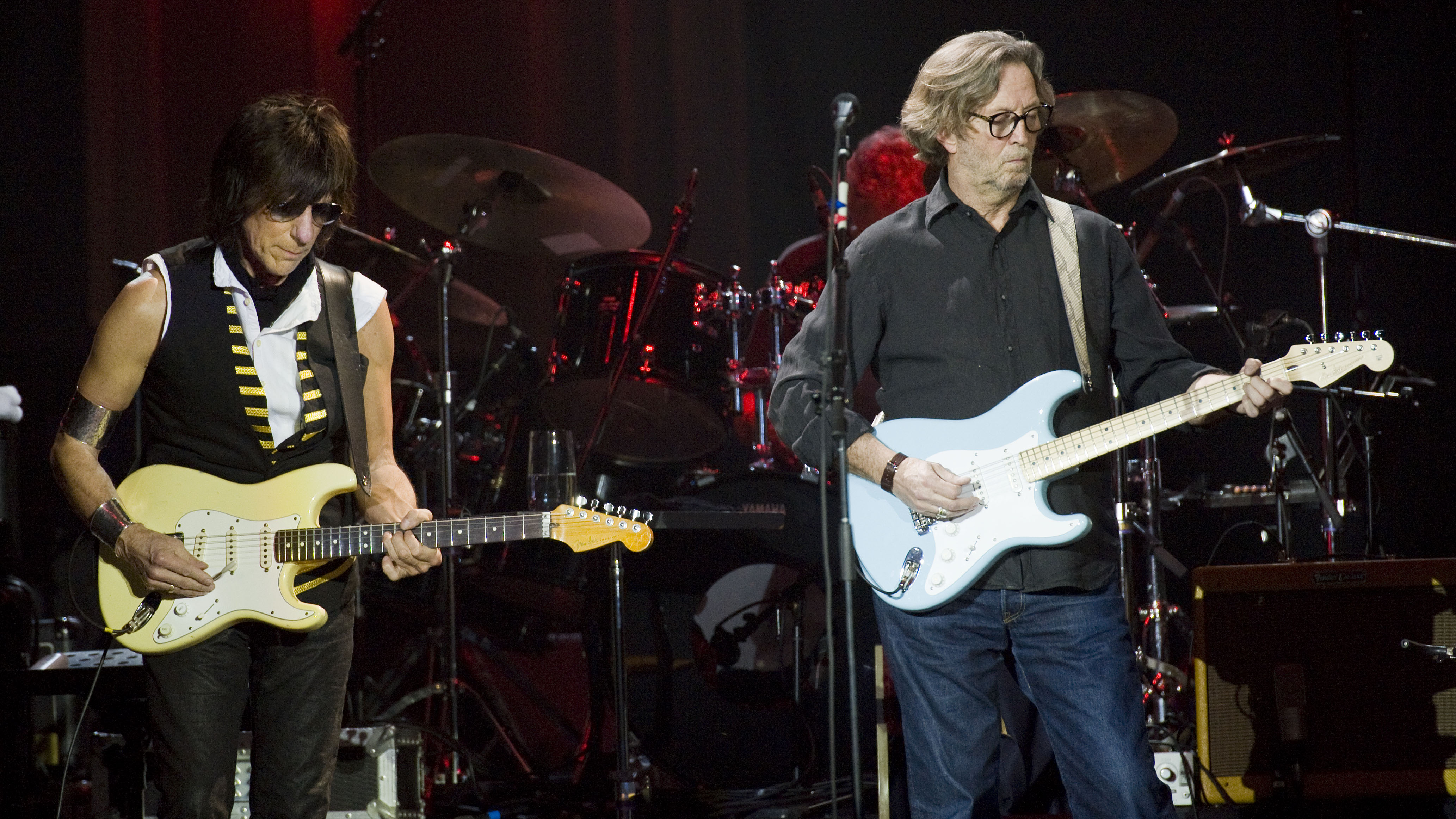

“It’s so difficult because I didn’t sing. Eric [Clapton] said, and it was words of great wisdom, ‘Get used to the fact that you hate your voice, because I did.’ And I went, ‘But you sound good, I sound unbearably bad. I loathe it. I would never enjoy it even if we had another single like [Hi Ho] Silver Lining, I just couldn’t bear it.’

"I listen to Jimi who had a peculiar voice and it wasn’t a great voice but it was just magic"

“He said, ‘I’m telling you, if you don’t, it’s going to be tough.’ And it was tough, but then I can turn around and say, ‘Blow By Blow, put that in your pipe and smoke it, mate.’ But he’s right, if I did come up with a song and everybody loved it, it would instil confidence automatically and I might even get to like what I sound like but letting that out there is more than I can bear.

“It’s just not me. I listen to Jimi who had a peculiar voice and it wasn’t a great voice but it was just magic. He never did scream, it was always the guitar that screamed for him and I still marvel at him even today. I never listened to more Jimi than I do now because I’ve got some really rare recordings, it’s just humiliating to know that he was doing that up to 1970, all in a period of about three and a half years.

“Things took a funny turn in the early 70s. It all turned out well when I heard John McLaughlin, because his performance on the Miles Davis Jack Johnson album and with Mahavishnu Orchestra said, ‘Here’s where you can go’. And every musician I knew was raving about them. I thought, ‘This is a little bit of me, this. I’ll have some of that.’ The mastery of the playing, it was unequalled.”

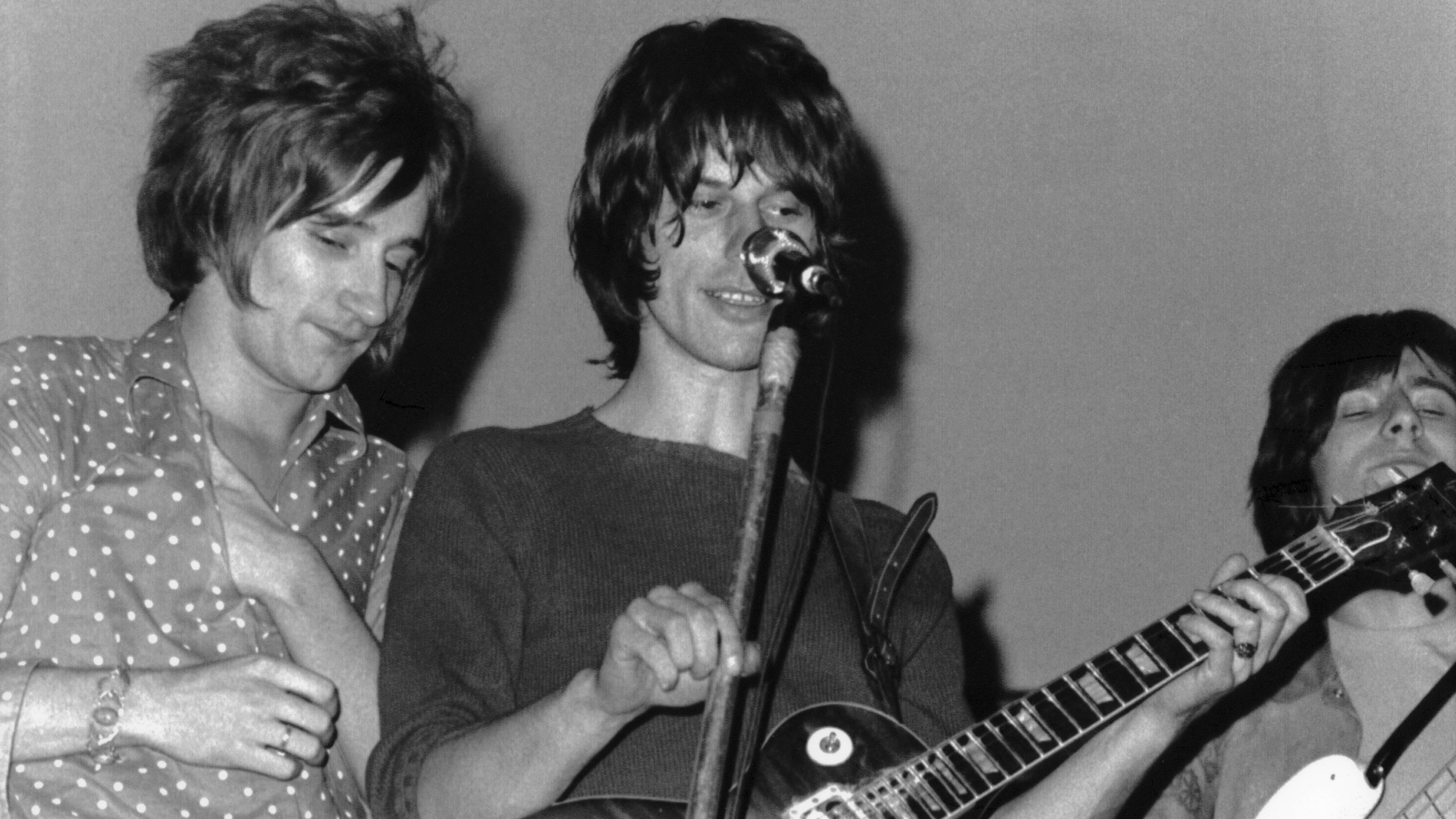

Your work in that first Jeff Beck group with Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood was so important in the development of the heavier side of blues-rock - were you trying to push the boundaries?

“What I was trying to do with Rod was take a little bit of Motown, put in some heavy backbeat. The drummer at the time was trained by one of the Motown drummers, who I think was over here on a Motown revue, so he had all the chops of Motown, but with more rock ’n’ roll power behind it for live stuff.

“The combination really worked, especially with Ronnie on bass. He played a big Fender with a Marshall and it was great and I think he’s a better bass player in some ways than he was a guitarist. And with Rod, it was like a black soul singer, the gruff voice - unfortunately it didn’t last long.

“We did all the dirty work over here and it wasn’t until we went to America that I was able to plug into my reputation from the Yardbirds for my first outing as a solo act and they just ate it up. Unfortunately, I don’t know what happened [with the band breaking up]. It was lack of material or I think Rod had it in his mind he was going to go long before I found out about it. I think he wanted to see his name up there instead of mine.”

How did you end up playing with Rod in the first place?

“Let’s not beat around the bush, I was pretty down at the time - I’d lost my girl, Hendrix had come and smeared everybody across the floor… it wasn’t looking too rosy. I’d fallen out with the Yardbirds - whatever happened I was out, and I’m facing a Monday morning just outside London thinking, What’s the point? It’s all gone against me. So I went to the Cromwell Inn, which was my last hope of preventing anything silly happening.

“It was the flattest, most boring Monday and I remember sitting there listening to Motown, thinking, this isn’t a bad move, such great songs, great playing - whoever the artist is, you know that those players are the same fabulous players that were the studio players.

“I looked up and there’s a bloke in the corner like that [slumped over] with a beer and I thought, ‘I’m getting out of here’, so I said, ‘Hey mate, you all right?’ He looked up and it was Rod. I said, ‘We’re both fucked. What about we go together and get a band?’ He went, ‘If you mean it, then put your number on this piece of paper.’

“I had a phone call, we arranged to meet and that’s how it started because I’d already heard him when he was with [English blues singer Long] John Baldry and really - I liked him better than Baldry. But he only did three or four songs as a guest. The next time I heard him was at a festival, Richmond I think it was. We played, and then he was on afterward with Baldry. The sound was blasting out of a big PA and I thought, ‘That man, there he is, that’s the geezer we need!’ And I never did anything about it because he was already involved with them.

“Then I heard that he might be free, and as luck would have it, he was the last, dying ember in this club I was in, and I’m glad I went! It’s always a good idea to go out somewhere, because you’re not going to have anybody knocking on the door, are you?”

"Billy Gibbons, when he was in The Moving Sidewalks, said that when we appeared at this club, his life changed"

Ronnie has said that he used to use a coin instead of a pick when he played bass…

“He may well have done. Out of his comfort zone, that’s fine because you don’t get too fancy, you just play the raw bass ingredient. Good fun, in fact it gave birth to Aerosmith - they told me it did! Billy Gibbons, when he was in The Moving Sidewalks, said that when we appeared at this club, his life changed. I don’t know if it was for the better, but he’d never seen amps that touched the ceiling.”

Would you play with Rod and Ronnie again some day?

“Yeah, I asked him to do the Hollywood Bowl gig that’s coming up. With Woody, I kept bumping into Woody at parties over Christmas, I said, ‘Listen, I’m not going to contact him. If you want to do the Jeff Beck Group, you’ve got to get Rod.’ He goes, ‘Oh, he’s up for it! You need to talk to Arnold (Rod’s manager).’ I thought, ‘No, I’m not talking to Arnold.’

“The next thing I know Ronnie says, ‘Sorry, Rod would love to do it but he’s doing Vegas.’ I said to him, ‘Why doesn’t he get on a jet and come? If he does the Vegas show early and gets on a plane, he could be in LA in 35 minutes!’ But it’s not going to work out. Really, he’s a Vegas singer now [the pair end up reuniting for the first time in a decade at the encore of Stewart's Hollywood Bowl gig on 27 September 2019]. You can’t be 11 again, you can’t put your jeans on and start shouting and screaming [laughs].”

There’s a huge difference between the first Jeff Beck Group albums, with their soul and R&B, and the fusion on Blow By Blow. Was that John McLaughlin’s influence?

“That was always lurking because of the mastery of the playing, it was unequalled and I don’t think there will ever be a four-piece with that kind of [talent]… it’s as peculiar as the gathering of the Monty Python guys.

"The incredible individual talent of those players - they had Billy Cobham for crying out loud, he became a household name. Jan Hammer. I was so thrilled to have Jan for two years and for him to be enthusiastic about being on an album and a tour. It was just a natural thing, to follow your heart. That’s what I do and so far it has served me quite well.”

“I feel like that song had everything we needed to come back with”: Bring Me The Horizon’s Lee Malia on Shadow Moses, its riff and the secrets behind its tone, and why it was the right anthem at the right time

“I’m beyond excited to introduce the next evolution of the MT15”: PRS announces refresh of tube amp lineup with the all-new Archon Classic and a high-gain power-up for the Mark Tremonti lunchbox head