Jean-Michel Jarre: "I always considered stereo to be a fake process, created in the ‘30s, just to produce a sense of space"

We sat down with the legendary composer to talk through his new live album and his fascination with immersive sound and VR technology

Jean-Michel Jarre likely needs no introduction. As one of the most prolific and successful composers to work in electronic music, it’s no exaggeration to say that he’s played a pivotal role in the development of the genre over the past five decades.

Aside from his recorded work, it’s Jarre’s magnificent, record-breaking live performances that stand out as landmark moments in his career, which have seen him bring millions of spectators together in the same place, while developing innovative sequencers and imaginative instruments specifically for use on stage.

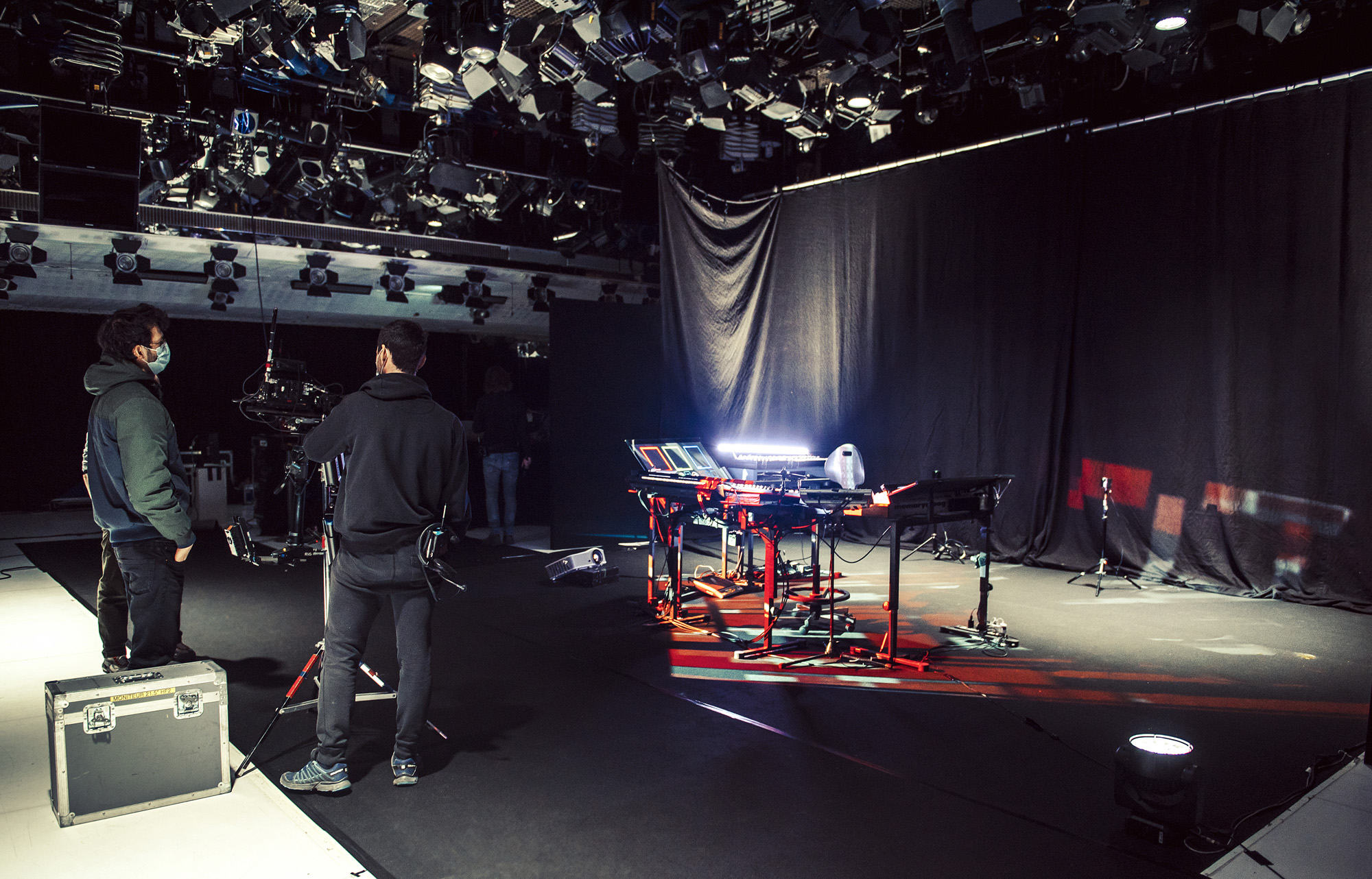

On 31 December 2020, Jarre masterminded a spectacle like no other. As the clock approached midnight, he performed live from his Parisian studio, projecting a digital avatar into a VR Notre-Dame that was populated by a virtual audience, streaming the show from around the world.

The 50-minute performance enlisted the talents of a hundred artists and technicians, and was ultimately viewed by over 75 million fans. Now, Jarre is releasing the binaural audio from the event as a live album, Welcome to the Other Side.

Ahead of the album’s release, we spoke with Jarre about his approach to live performance, his growing interest in VR and AR technology, and how embracing uncertainty can yield fascinating results.

What is it about live performance that captures your interest as a musician?

“It’s a main counterpoint to the studio work. Being a musician these days is a schizophrenic activity; when you work in the studio then after a while you want to go on tour, then when you’re touring, after a while you want to go back to the studio. It’s like walking with two legs as a musician.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Having said that, we know that lots of people are writing music and not touring. This is actually a wider issue - these days, in terms of economy, everybody says that the music industry can only survive because of live performance.

"Which, when you think about it, is quite unfair - you have lots of people who are great songwriters, great musicians, but they don’t have the ability, or don’t want to, perform on stage.

“This is something that, because of the pandemic, we should really think carefully about. Not giving the responsibility to the streaming platforms, to the economy of the internet, but also to ourselves. We should stop considering music to be as free as the air we breathe.

One day I played the tape backwards and I thought that aliens were talking to me

“The fact that for a while we were not able to perform - I hope that it will allow us to change our priorities a little bit, to recognise that music in itself, that you can listen to apart from the live performance, has value of its own.”

Can you remember the first time you performed live? Where was it, and what were you playing?

“When I was a teenager, I played in some local rock bands when I was 13, 14 years old. Playing live was the only way to share music and, of course, it was really fun. I remember the first time we had a performance - it was a very humble attempt, with very rough equipment. Some amplifier that one guy had built for me, for my guitar.

“In those days, my grandfather was an inventor and an engineer. He actually developed one of the first mixing desks for radio stations, and also he invented one of the first portable turntables, the ancestor of the iPod. He gave me, when I was 11 years old, a second-hand German tape recorder. I was obsessed, recording everything.

“One day I played the tape backwards and I thought that aliens were talking to me [laughs]. From that moment I started to experiment, processing sounds with some of my guitar or organ, with tape effects. Even for these first performances I was doing, I had these old tape recorders to create these strange sounds.”

Why did you choose to record and release your latest live album as a binaural recording?

“This album is based on quite a special project I worked on during the pandemic. It’s a live, VR performance. Not a pre-recorded experience, but a real live performance. I was playing live in a recording studio in the centre of Paris, and then my avatar was playing in a virtual Notre-Dame, in front of an audience of virtual avatars.

“So it was a real multi-platform performance, broadcast on radio, TV, streaming platforms across the West, and Asia too. It was followed by 75 million people. We were not expecting this at all.

“I’ve always been very interested in immersive processes, both in visuals and in sound. Binaural, 5.1, spatial audio, they’re all something I’ve been involved with for a long time. I think for one very simple reason: I always considered stereo to be a fake process, created in the ‘30s, just to produce a sense of space.

“Stereo doesn’t exist in nature, it’s something that has been created. In nature, everything is mono. When I talk to you, I’m in mono, when somebody is playing an instrument, it’s in mono. What creates the space is the space between the source and your ears. In that sense, having a number of mono channels is much more logical than anything else.”

These days, everybody’s obsessed with making instruments smaller and smaller.

“It was quite difficult, until we started to get convincing results without using very expensive equipment. Recently, the progress of binaural, which allows you to get this immersive sound with headphones, is something I’ve been very interested in. We mixed this project in the Innovation studio, run by France’s equivalent of the BBC, and we got quite a convincing result.

“You know, of course, that both Sony and Apple are announcing their versions of this technology, Spatial Audio and such. It’s a sign of the times. However, I’m convinced that it’ll only work when the artists or musicians are thinking of the music from the very beginning as made for Spatial Audio, producing and mixing it for binaural or multi-channel. Taking an existing stereo mix and processing it to fit into this format doesn’t work.”

How about virtual reality - what led you to use this technology for the Welcome to the Other Side concert?

“I’m a huge fan of VR. I think it’s going to be a very popular mode of expression in the future. It’s not only something that is in competition with live music. VR, AR and XR in general, makes me think of the early days of cinema, when movies were projected in circuses at the end of the 19th century.

“A lot of people from live theatre were looking at this as a curiosity, a magic trick, saying that yes it’s fun, seeing these people moving on the wall, but they’re not real actors. They’re not on stage in front of an audience. Then cinema became the major art form that it is today.

“I think that, for VR, it’s not only something for video games, it’s a real medium in itself. In that sense, Covid and the pandemic has accelerated all these new ways of expressing ourselves and sharing music with people who are geographically or socially isolated.

"The thrill of getting together in the same ‘place’, wherever you are, with a VR performance - you are on a virtual stage, but with an audience. People are sharing the same experience, but some are in China, Brazil, the US or Africa, and they’re sharing the same emotions at the same time. That’s quite exciting and quite new.”

Did it still feel like a live performance, playing from your studio as a digital avatar?

“What is quite strange, and even almost scary in a sense, is after five minutes you forget that you’re not really there. I was playing with my real instruments but with my VR headset on, and I was feeling my keyboards and synths under my hands, but I was also - without latency - in front of an audience of avatars.

“Very quickly, you forget that you are in front of avatars. These people behind them are real, they’re sending you images, clapping and dancing like in the real situation. It’s quite amazing how real it is, almost like being in a sci-fi movie. Like a Matrix world, but not in a dystopian way, a positive way instead.”

I shared this uncertainty and vulnerability with the crowd. And they actually adored it.

Can you give us an insight into the equipment you’re using for your live shows at the moment?

“I’m using a mix of analogue gear. I have a Memorymoog, I’m using an Italian modular synth, the GR-8, which is quite amazing. It’s modular but, instead of cables, these guys have used switches, it’s quite cool. I’m always using a VCS3, from EMS, it’s my pet [laughs]. It was my first instrument, so I always have this on stage.

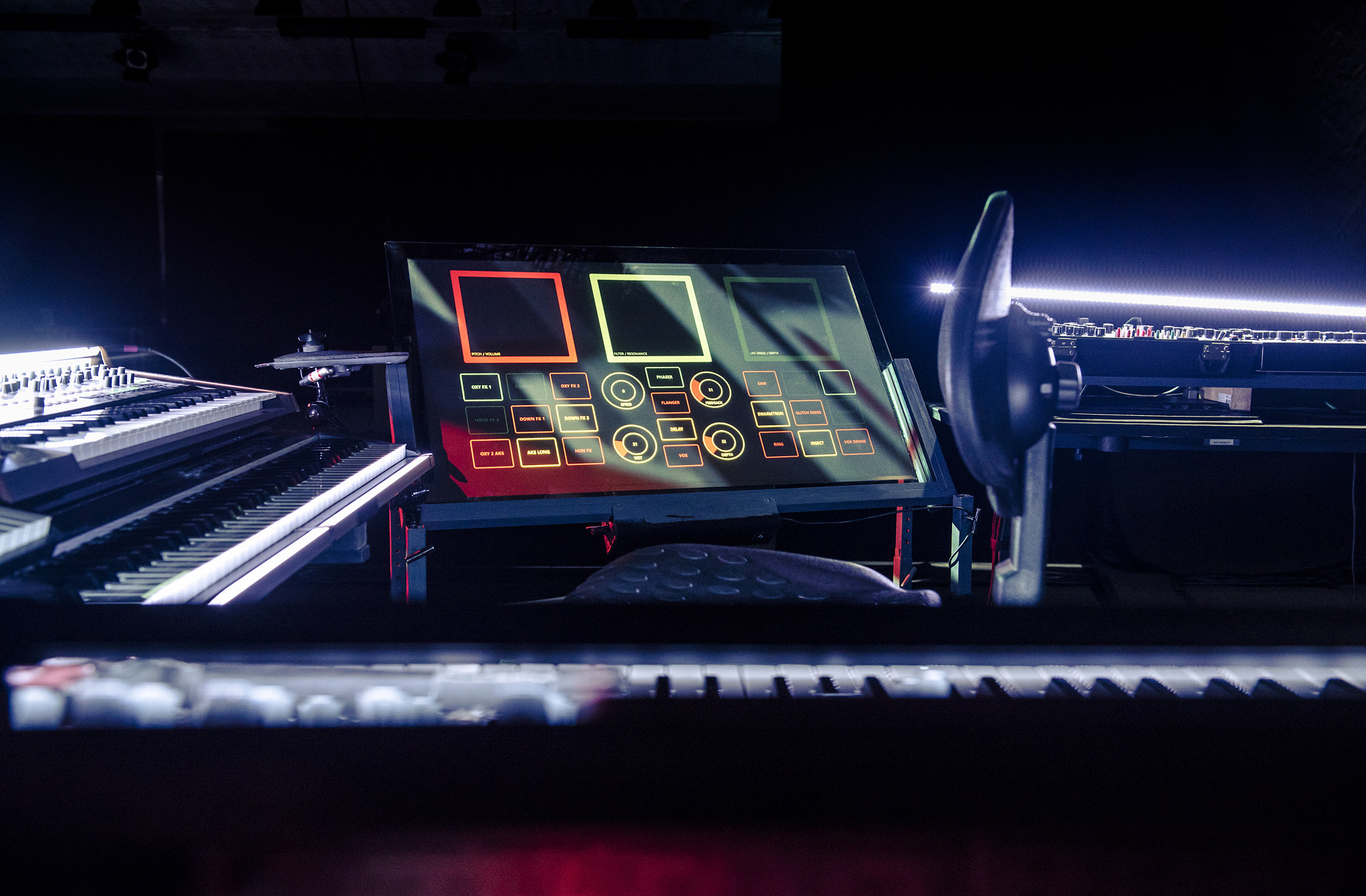

“I’m also using an instrument we developed - there’s a big glass touchscreen, 1m 20 by 60-70 centimetres, which I use as a big iPad, to control effects and sequences. That reminds me of a discussion I had with lots of developers - these days, everybody’s obsessed with making instruments smaller and smaller.

"OK, it’s cool, having everything in your rucksack. But if you ask somebody playing the guitar, piano, or double bass, any instrument - they’re not trying to get a tiny saxophone or violin, just so they can travel with it in their pocket.

“When you are on stage, you need to share with the audience the idea of the performance. There’s excitement in the physical involvement of the performer. The human body has a kind of proportion, we’re not small people, we have a certain ergonomy we should respect. I try to get some instruments on stage that are a decent size.

“It’s an improvement that developers should think about, having a proper interface that’s not just 20, 30 centimetres wide. Something larger, like a drummer has, or a guitarist has, where you can really involve yourself physically. To express more clearly what you are doing, rather than being quite mysterious behind your small laptop.”

What do you think is the most important thing to remember when translating recorded music into a live show?

“Only the result matters. Especially in electronic music performance, the visual is very important, and your performance as a performer on stage is very important. It’s the reason why I tried to create these instruments, the laser harp, instruments which enable you to really play live. To try to share a feeling of excitement and energy coming from the stage.

“As you know I was one of the first to integrate, at the beginning of my career, visuals with electronic music. In those days it didn’t exist. At a very early stage I realised that the visual elements in electronic music are like the modern version of opera, in the old days, when the classical composers were working with carpenters and painters to create an enhanced performance with set design. This is part of the vocabulary of electronic music, and all music performed on stage.

“Also, what’s important is the perception of accidents. The fact that in live performance you must keep this idea of uncertainty. So that not everything is planned and pre-recorded. I remember that a few years ago we decided to do a series of very minimalist concerts promoting Oxygene live, without MIDI, without anything.

“Basically this album I recorded on an 8-track recorder, so we had eight elements being performed all the time. We were a four-person band, so we had eight hands. Eight hands, able to play every single part totally live. That was quite crazy because we had instruments like old Mellotrons, and my Memorymoog was crashing very often.

“Rather than hiding these accidents, I played with that and shared this uncertainty and vulnerability with the crowd. And they actually adored it, they loved it. Because suddenly, they were experiencing a work in progress, in a sense.”

What are your plans for your next project?

“We are still in a state of uncertainty, not knowing what’s going to happen for live performances in the next few weeks or months, at least until the end of the year. I don’t have an immediate live project in the next few weeks. I am thinking seriously of going back on stage next year.”

“This whole period has changed the ideas I have for future live performances. I would like to go for a more “phy-gital” approach, mixing live performance with VR, augmented reality elements.

"This period has changed, and will change, the way we perform. We have so many possibilities coming with XR and AI, and I would like to explore all of these techniques with my next stage project. Aside from that, I’ll be taking the opportunity to write some new music.”

I'm MusicRadar's Tech Editor, working across everything from product news and gear-focused features to artist interviews and tech tutorials. I love electronic music and I'm perpetually fascinated by the tools we use to make it. When I'm not behind my laptop keyboard, you'll probably find me behind a MIDI keyboard, carefully crafting the beginnings of another project that I'll ultimately abandon to the creative graveyard that is my overstuffed hard drive.

“I’m looking forward to breaking it in on stage”: Mustard will be headlining at Coachella tonight with a very exclusive Native Instruments Maschine MK3, and there’s custom yellow Kontrol S49 MIDI keyboard, too

“Turns out they weigh more than I thought... #tornthisway”: Mark Ronson injures himself trying to move a stage monitor